Parley P. Pratt in Winter Quarters and the Trail West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work PROFESSIONAL TRACK 2009-present Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 2003-2009 Associate Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1997-2003 Assistant Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1994-99 Faculty, Department of Ancient Scripture, BYU Salt Lake Center 1980-97 Department Chair of Home Economics, Jordan School District, Midvale Middle School, Sandy, Utah EDUCATION 1997 Ed.D. Brigham Young University, Educational Leadership, Minor: Church History and Doctrine 1992 M.Ed. Utah State University, Secondary Education, Emphasis: American History 1980 B.S. Brigham Young University, Home Economics Education HONORS 2012 The Harvey B. Black and Susan Easton Black Outstanding Publication Award: Presented in recognition of an outstanding published scholarly article or academic book in Church history, doctrine or related areas for Against the Odds: The Life of George Albert Smith (Covenant Communications, Inc., 2011). 2012 Alice Louise Reynolds Women-in-Scholarship Lecture 2006 Brigham Young University Faculty Women’s Association Teaching Award 2005 Utah State Historical Society’s Best Article Award “Non Utah Historical Quarterly,” for “David O. McKay’s Progressive Educational Ideas and Practices, 1899-1922.” 1998 Kappa Omicron Nu, Alpha Tau Chapter Award of Excellence for research on David O. McKay 1997 The Crystal Communicator Award of Excellence (An International Competition honoring excellence in print media, 2,900 entries in 1997. Two hundred recipients awarded.) Research consultant for David O. McKay: Prophet and Educator Video 1994 Midvale Middle School Applied Science Teacher of the Year 1987 Jordan School District Vocational Teacher of the Year PUBLICATIONS Authored Books (18) Casey Griffiths and Mary Jane Woodger, 50 Relics of the Restoration (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Press, 2020). -

Joseph Smith Ill's 1844 Blessing Ana the Mormons of Utah

Q). MicAael' J2umw Joseph Smith Ill's 1844 Blessing Ana The Mormons of Utah JVlembers of the Mormon Church headquartered in Salt Lake City may have reacted anywhere along the spectrum from sublime indifference to temporary discomfiture to cold terror at the recently discovered blessing by Joseph Smith, Jr., to young Joseph on 17 January 1844, to "be my successor to the Presidency of the High Priesthood: a Seer, and a Revelator, and a Prophet, unto the Church; which appointment belongeth to him by blessing, and also by right."1 The Mormon Church follows a line of succession from Joseph Smith, Jr., completely different from that provided in this document. To understand the significance of the 1844 document in relation to the LDS Church and Mormon claims of presidential succession from Joseph Smith, Jr., one must recognize the authenticity and provenance of the document itself, the statements and actions by Joseph Smith about succession before 1844, the succession de- velopments at Nauvoo after January 1844, and the nature of apostolic succes- sion begun by Brigham Young and continued in the LDS Church today. All internal evidences concerning the manuscript blessing of Joseph Smith III, dated 17 January 1844, give conclusive support to its authenticity. Anyone at all familiar with the thousands of official manuscript documents of early Mormonism will immediately recognize that the document is written on paper contemporary with the 1840s, that the text of the blessing is in the extraordinar- ily distinctive handwriting of Joseph Smith's personal clerk, Thomas Bullock, that the words on the back of the document ("Joseph Smith 3 blessing") bear striking similarity to the handwriting of Joseph Smith, Jr., and that the docu- ment was folded and labeled in precisely the manner all one-page documents were filed by the church historian's office in the 1844 period. -

George Became a Member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints As a Young Man, and Moved to Nauvoo, Illinois

George became a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a young man, and moved to Nauvoo, Illinois. Here he met and married Thomazine Downing on August 14, 1842. George was a bricklayer, so he was busy building homes in Nauvoo and helping on the temple. When the Saints were driven out of Nauvoo in 1846, George and Thomazine moved to Winter Quarters. Here George, age 29, was asked to be a member of Brigham Young’s Vanguard Company headed to the Salt Lake Valley. They made it to the Valley on July 24, 1847. While George was gone from Winter Quarters, his brother, William Woodward, died in November 1846 at Winter Quarters. He was 37 years of age. In August 1847, George headed back to Winter Quarters, but on the way met his wife coming in the Daniel Spencer/Perrigrine Sessions Company, so he turned around and returned to the Salt Lake Valley with his wife. They arrived back in the Valley the end of September 1847. There are no children listed for George and Thomazine. In March 1857, George married Mary Ann Wallace in Salt Lake City. Mary Ann had immigrate to the Valley with her father, Neversen Grant Wallace, in the Abraham O. Smoot Company. There is one daughter listed for them, but she died at age one, in August 1872, after they had moved to St. George, Utah. George moved to St. George in the summer of 1872. For the next several years, George was busy establishing his home there and helping this community to grow. -

NAUVOO's TEMPLE It Was Announced August 31, 1840, That A

NAUVOO’S TEMPLE Dean E. Garner—Institute Director, Denton, Texas t was announced August 31, 1840, that a temple would be built, and Iarchitectural plans began to come in. Joseph Smith “advertised for plans for the temple,” William Weeks said, “and several architects presented their plans. But none seemed to suit Smith. When [William] presented his plans, Joseph Smith grabbed him, hugged him and said, ‘You are the man I want.’”1 Thus William was made superintendent of temple construction. All his work was cleared by the temple building committee. Those on the committee were Reynolds Cahoon, Elias Higbee, and Alpheus Cutler.2 Joseph Smith had the final say pertaining to the details of the temple, for he had seen the temple in vision, which enabled him to make decisions on the temple’s appearance.3 During the October Conference of 1840, the building of the Nauvoo During the temple was voted on and accepted by the saints. The temple was to be October Conference constructed of stone. Many weeks preceding the conference, a survey of Nauvoo’s main street verified that the entire route was underlain with a of 1840, the building massive layer of limestone many feet thick, particularly so in the northern of the Nauvoo part of the community. That site was selected for the quarry, where quality white-gray Illinois limestone could be extracted for the construction of temple was voted the temple. The principal quarry from which the temple stone would on and accepted by come was opened within ten days of the conference. Work in the quarry began October 12, 1840, with Elisha Everett striking the first blow.4 the saints. -

The Response to Joseph Smith's Innovations in the Second

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2011 Recreating Religion: The Response to Joseph Smith’s Innovations in the Second Prophetic Generation of Mormonism Christopher James Blythe Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blythe, Christopher James, "Recreating Religion: The Response to Joseph Smith’s Innovations in the Second Prophetic Generation of Mormonism" (2011). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 916. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/916 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECREATING RELIGION: THE RESPONSE TO JOSEPH SMITH’S INNOVATIONS IN THE SECOND PROPHETIC GENERATION OF MORMONISM by Christopher James Blythe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: _________________________ _________________________ Philip L. Barlow, ThD Daniel J. McInerney, PhD Major Professor Committee Member _________________________ _________________________ Richard Sherlock, PhD Byron R. Burnham, EdD Committee Member Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2010 ii Copyright © Christopher James Blythe 2010 All rights reserved. iii ABSTRACT Recreating Religion: The Response to Joseph Smith’s Innovations in the Second Prophetic Generation of Mormonism by Christopher James Blythe, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2010 Major Professor: Philip Barlow Department: History On June 27, 1844, Joseph Smith, the founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was assassinated. -

Nauvoo Legion Officers, 1841–1843

Nauvoo Legion Officers Th e charter for the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, approved 16 December 1840, allowed for the formation of the Nauvoo Legion, a unit of the Illinois state militia. Th e city council passed an ordinance offi cially organizing the Nauvoo Legion on 3 February 1841. Th e fi rst meeting of the legion was held on 4 February 1841, when John C. Bennett, Don Carlos Smith, and other commissioned offi cers of the Illinois state militia elected the general offi - cers of the legion. Other positions were fi lled during the following months. Th e Nauvoo Legion comprised two brigades, or “cohorts,” each headed by a brigadier general. Th e fi rst cohort consisted of cavalry and the second of infantry and artillery troops. Offi cers retained their rank unless terminated by resignation, death, or cashiering out of the Nauvoo Legion. At its largest, the legion numbered between two thousand and three thousand men. Th e following chart identifi es the staff s of the lieutenant general, major general, and brigadier generals of the Nauvoo Legion, and the men who held the various offi ces between February 1841 and April 1843. Names are followed by the date of rank; dates of formal com- mission by the governor, when known, are provided in parentheses. Ending dates are not given except in cases of termination. Positions, dates of rank, and commission dates are taken from returns to the adjutant general of the state and records of the Illinois state militia. OFFICE 1841 1842 1843 Lieutenant General’s Staff Lieutenant General Joseph Smith Jr. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005

Journal of Mormon History Volume 31 Issue 3 Article 1 2005 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2005) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 31 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol31/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES • --The Case for Sidney Rigdon as Author of the Lectures on Faith Noel B. Reynolds, 1 • --Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith: Genealogical Applications Ugo A. Perego, Natalie M. Myres, and Scott R. Woodward, 42 • --Lucy's Image: A Recently Discovered Photograph of Lucy Mack Smith Ronald E. Romig and Lachlan Mackay, 61 • --Eyes on "the Whole European World": Mormon Observers of the 1848 Revolutions Craig Livingston, 78 • --Missouri's Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons Stephen C. LeSueur, 113 • --Artois Hamilton: A Good Man in Carthage? Susan Easton Black, 145 • --One Masterpiece, Four Masters: Reconsidering the Authorship of the Salt Lake Tabernacle Nathan D. Grow, 170 • --The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism Ronald W. Walker, 198 • --Kerstina Nilsdotter: A Story of the Swedish Saints Leslie Albrecht Huber, 241 REVIEWS --John Sillito, ed., History's Apprentice: The Diaries of B. -

Early Marriages Performed by the Latter-Day Saint Elders in Jackson County, Missouri, 1832-1834

Scott H. Faulring: Jackson County Marriages by LDS Elders 197 Early Marriages Performed by the Latter-day Saint Elders in Jackson County, Missouri, 1832-1834 Compiled and Edited with an Introduction by Scott H. Faulring During the two and a half years (1831-1833) the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints lived in Jackson County, Missouri, they struggled to establish a Zion community. In July 1831, the Saints were commanded by revelation to gather to Jackson County because the Lord had declared that this area was “the land of promise” and designat- ed it as “the place for the city of Zion” (D&C 57:2). During this period, the Mormon settlers had problems with their immediate Missourian neighbors. Much of the friction resulted from their religious, social, cultural and eco- nomic differences. The Latter-day Saint immigrants were predominantly from the northeastern United States while the “old settlers” had moved to Missouri from the southern states and were slave holders. Because of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Missouri was a slave state. Eventually, by mid-July 1833, a militant group of Jackson County Missourians became intolerant of the Mormons and began the process of forcefully expelling them from the county.1 And yet in spite of these mounting hostilities, a little-known aspect of the Latter-day Saints’ stay in Jackson County is that during this time, the Mormon elders were allowed to perform civil marriages. In contrast to the legal difficulties some of the elders faced in Ohio, the Latter-day Saint priest- hood holders were recognized by the civil authorities as “preachers of the gospel.”2 Years earlier, on 4 July 1825, Missouri enacted a statute entitled, “Marriages. -

Augustine Spencer: Nauvoo Gentile, Joseph Smith Antagonist

Sadler and Sadler: Augustine Spencer 27 Augustine Spencer: Nauvoo Gentile, Joseph Smith Antagonist Richard W. Sadler and Claudia S. Sadler Daniel Spencer Sr., his wife Chloe, and sons Daniel Jr., Orson, and Hi- ram Spencer and their families were devoted Nauvoo Mormons. However, in the six months preceding Joseph Smith’s death, their eldest son, Augustine Spencer, who also lived in Nauvoo, but who remained aloof from the Church, turned antagonistic toward his family, became an outspoken critic against the Church, and participated in the activities that led to Joseph Smith’s arrest and death at Carthage. How and why Augustine’s antagonism toward Mormonism developed provides a historical case study that sheds light on the complex religious, cultural, and social dynamics of nineteenth-century society and the Spencer family. The Daniel Sr. and Chloe Wilson Spencer Family Daniel Spencer Sr., born August 26, 1764, spent his early years in East Haddam, Connecticut, on the Connecticut River. His ancestors had arrived in Massachusetts during the first decade of the great Puritan migration of the RICH A RD W. SA DLER ([email protected])is a professor of history and former dean of the college of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Weber State University. He received his BS, MS, and PhD degrees from the University of Utah. He specializes in nineteenth century US history. He is a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society, former editor of the Journal of Mormon History, past president of the Mormon History Association, and past chair of the Utah State Board of Education. CL A UDI A SPENCER SA DLER ([email protected]) received her undergraduate education at the University of Utah and Weber State University. -

“A Room of Round Logs with a Dirt Roof”: Ute Perkins' Stewardship To

Eugene H. & Waldo C. Perkins: Ute Perkins Stewardship 61 “A Room of Round Logs with a Dirt Roof”: Ute Perkins’ Stewardship to Look after Mormon Battalion Families Eugene H. Perkins & Waldo C. Perkins On 17 July1846, one day after Captain James Allen had mustered in the Mormon Battalion, U.S. Army of the West, Brigham Young called eighty- nine bishops1 to look after the wives and families of the Mormon Battalion.2 Among the group called were Ute Perkins (1816–1901), a thirty-year-old member of seven years, his uncles, William G. Perkins and John Vance, and his first cousin, Andrew H. Perkins. Until Nauvoo, the Church’s two general bishops, Bishop Newel K. Whitney in Kirtland and Bishop Edward Partridge in Missouri, bore as their major responsibility the challenge to care for the poor and needy. In Nauvoo, in addition to the general bishops, the Church initiated the prac- tice of assigning bishops to aid the poor within Nauvoo’s municipal wards— hence the beginnings of ward bishops. During the trek west, as the calling of these eighty-nine bishops shows, the commitment to calling local bishops to care for small membership groupings was underway and became enough of an established practice that in Utah it became standard Church administra- tive practice—a presiding bishopric at the general level and ward bishops at the local level. Therefore, study of the bishops’ work during the Winter Quarters period deserves historical attention, to which effort the following material contributes.3 Ute Perkins lived in a temporary Mormon encampment called Pleasant Valley, where his father Absalom was the branch president. -

Sources of Mormon History in Illinois, 1839-48: an Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University

BIBLIOGRAPHIC CONTRIBUTIONS NO. Sources of Mormon History in Illinois, 1839-48: An Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University Compiled by STANLEY B. KIMBALL 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, 1966 The Library SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Carbondale—Edwardsville Bibliographic Contributions No. 1 SOURCES OF MORMON HISTORY IN ILLINOIS, 1839-48 An Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, 1966 Compiled by Stanley B. Kimball Central Publications Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois ©2014 Southern Illinois University Edwardsville 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, May, 1966 FOREWORD In the course of developing a book and manuscript collection and in providing reference service to students and faculty, a univeristy library frequently prepares special bibliographies, some of which may prove to be of more than local interest. The Bibliographic Contributions series, of which this is the first number, has been created as a means of sharing the results of such biblio graphic efforts with our colleagues in other universities. The contribu tions to this series will appear at irregular intervals, will vary widely in subject matter and in comprehensiveness, and will not necessarily follow a uniform bibliographic format. Because many of the contributions will be by-products of more extensive research or will be of a tentative nature, the series is presented in this format. Comments, additions, and corrections will be welcomed by the compilers. The author of the initial contribution in the series is Associate Professor of History of Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville, Illinois. He has been engaged in research on the Nauvoo period of the Mormon Church since he came to the university in 1959 and has published numerous articles on this subject. -

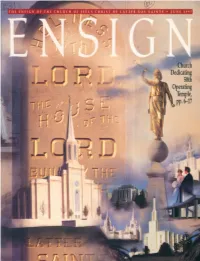

Church Dedicating 50Th Operating Temple, Pp

Church Dedicating 50th Operating Temple, pp. 6-17 THE PIONEER TREK NAUVOO TO WINTER QUARTERS BY WILLIAM G. HARTLEY Latter-day Saints did not leave Nauvoo, Illinois, tn 1846 tn one mass exodus led by President Brigham Young but primarily tn three separate groups-tn winter, spring, and fall. Beginning in February 1846, many Latter-day Saints were found crossing hills and rivers on the trek to Winter Quarters. he Latter-day Saints' epic evacuation from Nauvoo, ORIGINAL PLAN WAS FOR SPRING DEPARTURE Illinois, in 1846 may be better understood by com On 11 October 1845, Brigham Young, President and Tparing it to a three-act play. Act 1, the winter exo senior member of the Church's governing Quorum of dus, was President Brigham Young's well-known Camp Twelve Apostles, responded in behalf of the Brethren to of Israel trek across Iowa from 1 March to 13 June 1846, anti-Mormon rhetoric, arson, and assaults in September. involving perhaps 3,000 Saints. Their journey has been He appointed captains for 25 companies of 100 wagons researched thoroughly and often stands as the story of each and requested each company to build its own the Latter-day Saints' exodus from Nauvoo.1 Act 2, the wagons to roll west in one massive 2,500-wagon cara spring exodus, which history seems to have overlooked, van the next spring.2 Church leaders instructed mem showed three huge waves departing Nauvoo, involving bers outside of Illinois to come to Nauvoo in time to some 10,000 Saints, more than triple the number in the move west in the spring.