Sutherland and Caithness in Saga--Time Or, the Jarls and the Freskyns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Highland Council Election, Thursday 6 May 1999 - Results

The Highland Council Election, Thursday 6 May 1999 - Results CANDIDATE DESCRIPTION VOTES MAJORITY %POLL 1. Caithness North West MacDonald, Alastair I Lib Dem 680 278 58.3% Mowat, John M* Ind 408 2. Thurso West Bruce, George - 357 Fry, James H Thurso Ind 407 47 61.5% Saxon, Eric R Scot Labour 454 3. Thurso Central Henderson, Ronald S Ind 198 Macdonald, Elizabeth - 482 71 58.9% C* Rosie, John S Scot Labour 553 4. Thurso East Waters, Donald M F* - Returned unopposed 5. Caithness Central Flear, David C M Scot Lib Dem Returned unopposed 6. Caithness North East Green, John H* - 793 213 69.7% Richard, David A Ind 580 7. Wick Mowat, Bill Scot Labour 402 Murray, Anderson* Ind 376 45 59.2% Smith, Graeme M Scot Lib Dem 447 8. Wick West Fernie, William N Ind 438 Roy, Alistair A Ind 333 25 59.1% Steven, Deirdre J. Scot Labour 463 9. Pultneytown Oag, James William* - 673 236 55.8% Smith, Niall - 437 10. Caithness South East Calder, Jeanette M Ind 522 173 62.9% Mowat, William A* Ind Liberal 695 SUTHERLAND (6) 11. Sutherland North West Keith, Francis R M* - Returned unopposed 12. Tongue and Farr Jardine, Eirene B M Scot Lib Dem 539 25 67.0% Mackay, Alexander* Ind 514 13. Sutherland Central Chalmers, Alexander - 186 255 69.8% Magee, Alison L* Ind 725 Taylor, Russell Eugene Ind 470 14. Golspie and Rogart Houston, Helen M Ind 373 Ross, William J Ind 687 314 70.2% Scott, Valerie E R - 150 15. Brora Finlayson, Margaret W - 802 140 68.1% McDonald, Ronald R* Ind 662 16. -

BCS Paper 2016/13

Boundary Commission for Scotland BCS Paper 2016/13 2018 Review of Westminster Constituencies Considerations for constituency design in Highland and north of Scotland Action required 1. The Commission is invited to consider the issue of constituency size when designing constituencies for Highland and the north of Scotland and whether it wishes to propose a constituency for its public consultation outwith the electorate quota. Background 2. The legislation governing the review states that no constituency is permitted to be larger than 13,000 square kilometres. 3. The legislation also states that any constituency larger than 12,000 square kilometres may have an electorate lower than 95% of the electoral quota (ie less than 71,031), if it is not reasonably possible for it to comply with that requirement. 4. The constituency size rule is probably only relevant in Highland. 5. The Secretariat has considered some alternative constituency designs for Highland and the north of Scotland for discussion. 6. There are currently 3 UK Parliament constituencies wholly with Highland Council area: Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross – 45,898 electors Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey – 74,354 electors Ross, Skye and Lochaber – 51,817 electors 7. During the 6th Review of UK Parliament constituencies the Commission developed proposals based on constituencies within the electoral quota and area limit. Option 1 – considers electorate lower than 95% of the electoral quota in Highland 8. Option 1: follows the Scottish Parliament constituency of Caithness, Sutherland and Ross, that includes Highland wards 1 – 5, 7, 8 and part of ward 6. The electorate and area for the proposed Caithness, Sutherland and Ross constituency is 53,264 electors and 12,792 sq km; creates an Inverness constituency that includes Highland wards 9 -11, 13-18, 20 and ward 6 (part) with an electorate of 85,276. -

Cruising the ISLANDS of ORKNEY

Cruising THE ISLANDS OF ORKNEY his brief guide has been produced to help the cruising visitor create an enjoyable visit to TTour islands, it is by no means exhaustive and only mentions the main and generally obvious anchorages that can be found on charts. Some of the welcoming pubs, hotels and other attractions close to the harbour or mooring are suggested for your entertainment, however much more awaits to be explored afloat and many other delights can be discovered ashore. Each individual island that makes up the archipelago offers a different experience ashore and you should consult “Visit Orkney” and other local guides for information. Orkney waters, if treated with respect, should offer no worries for the experienced sailor and will present no greater problem than cruising elsewhere in the UK. Tides, although strong in some parts, are predictable and can be used to great advantage; passage making is a delight with the current in your favour but can present a challenge when against. The old cruising guides for Orkney waters preached doom for the seafarer who entered where “Dragons and Sea Serpents lie”. This hails from the days of little or no engine power aboard the average sailing vessel and the frequent lack of wind amongst tidal islands; admittedly a worrying combination when you’ve nothing but a scrap of canvas for power and a small anchor for brakes! Consult the charts, tidal guides and sailing directions and don’t be afraid to ask! You will find red “Visitor Mooring” buoys in various locations, these are removed annually over the winter and are well maintained and can cope with boats up to 20 tons (or more in settled weather). -

Volume of Minutes

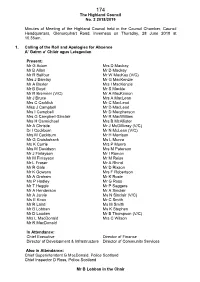

174 The Highland Council No. 2 2018/2019 Minutes of Meeting of the Highland Council held in the Council Chamber, Council Headquarters, Glenurquhart Road, Inverness on Thursday, 28 June 2018 at 10.35am. 1. Calling of the Roll and Apologies for Absence A’ Gairm a’ Chlàir agus Leisgeulan Present: Mr G Adam Mrs D Mackay Mr B Allan Mr D Mackay Mr R Balfour Mr W MacKay (V/C) Mrs J Barclay Mr G MacKenzie Mr A Baxter Mrs I MacKenzie Mr B Boyd Mr S Mackie Mr R Bremner (V/C) Mr A MacKinnon Mr J Bruce Mrs A MacLean Mrs C Caddick Mr C MacLeod Miss J Campbell Mr D MacLeod Mrs I Campbell Mr D Macpherson Mrs G Campbell-Sinclair Mr R MacWilliam Mrs H Carmichael Mrs B McAllister Mr A Christie Mr J McGillivray (V/C) Dr I Cockburn Mr N McLean (V/C) Mrs M Cockburn Mr H Morrison Mr G Cruickshank Ms L Munro Ms K Currie Mrs P Munro Mrs M Davidson Mrs M Paterson Mr J Finlayson Mr I Ramon Mr M Finlayson Mr M Reiss Mr L Fraser Mr A Rhind Mr R Gale Mr D Rixson Mr K Gowans Mrs F Robertson Mr A Graham Mr K Rosie Ms P Hadley Mr G Ross Mr T Heggie Mr P Saggers Mr A Henderson Mr A Sinclair Mr A Jarvie Ms N Sinclair (V/C) Ms E Knox Mr C Smith Mr R Laird Ms M Smith Mr B Lobban Ms K Stephen Mr D Louden Mr B Thompson (V/C) Mrs L MacDonald Mrs C Wilson Mr R MacDonald In Attendance: Chief Executive Director of Finance Director of Development & Infrastructure Director of Community Services Also in Attendance: Chief Superintendent G MacDonald, Police Scotland Chief Inspector D Ross, Police Scotland Mr B Lobban in the Chair 175 Apologies for absence were intimated on behalf of Mr I Brown, Mr C Fraser, Mr J Gordon, Mr J Gray and Mrs T Robertson. -

Gills Bay 132 Kv Environmental Statement: Volume 2: Main Report

Gills Bay 132 kV Environmental Statement: V olume 2: Main Report August 2015 Scottish Hydro Electric Transmission Plc Gills Bay 132 kV VOLUME 2 MAIN REPORT - TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Development Need 1.3 Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Screening 1.4 Contents of the Environmental Statement 1.5 Structure of the Environmental Statement 1.6 The Project Team 1.7 Notifications Chapter 2 Description of Development 2.1 Introduction 2.2 The Proposed Development 2.3 Limits of Deviation 2.4 OHL Design 2.5 Underground Cable Installation 2.6 Construction and Phasing 2.7 Reinstatement 2.8 Construction Employment and Hours of Work 2.9 Construction Traffic 2.10 Construction Management 2.11 Operation and Management of the Transmission Connection Chapter 3 Environmental Impact Assessment Methodology 3.1 Summary of EIA Process 3.2 Stakeholder Consultation and Scoping 3.3 Potentially Significant Issues 3.4 Non-Significant Issues 3.5 EIA Methodology 3.6 Cumulative Assessment 3.7 EIA Good Practice Chapter 4 Route Selection and Alternatives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Development Considerations 4.3 Do-Nothing Alternative 4.4 Alternative Corridors 4.5 Alternative Routes and Conductor Support Types within the Preferred Corridor Chapter 5 Planning and Policy Context 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Development Considerations 5.3 National Policy 5.4 Regional Policy Volume 2: LT000022 Table of Contents Scottish Hydro Electric Transmission Plc Gills Bay 132 kV 5.5 Local Policy 5.6 Other Guidance 5.7 Summary Chapter 6 Landscape -

Caithness County Council

Caithness County Council RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: CC Alternative reference number: Title: Caithness County Council Dates of creation: 1720-1975 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 10 bays of shelving Format: Mainly paper RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: Caithness County Council Administrative history: 1889-1930 County Councils were established under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. They assumed the powers of the Commissioners of Supply, and of Parochial Boards, excluding those in Burghs, under the Public Health Acts. The County Councils also assumed the powers of the County Road Trusts, and as a consequence were obliged to appoint County Road Boards. Powers of the former Police Committees of the Commissioners were transferred to Standing Joint Committees, composed of County Councillors, Commissioners and the Sheriff of the county. They acted as the police committee of the counties - the executive bodies for the administration of police. The Act thus entrusted to the new County Councils most existing local government functions outwith the burghs except the poor law, education, mental health and licensing. Each county was divided into districts administered by a District Committee of County Councillors. Funded directly by the County Councils, the District Committees were responsible for roads, housing, water supply and public health. Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archive 1 Provision was also made for the creation of Special Districts to be responsible for the provision of services including water supply, drainage, lighting and scavenging. 1930-1975 The Local Government Act (Scotland) 1929 abolished the District Committees and Parish Councils and transferred their powers and duties to the County Councils and District Councils (see CC/6). -

Caithness, Sutherland & Easter Ross Planning

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda Item CAITHNESS, SUTHERLAND & EASTER ROSS PLANNING Report No APPLICATIONS AND REVIEW COMMITTEE – 17 March 2009 07/00448/FULSU Construction and operation of onshore wind development comprising 2 wind turbines (installed capacity 5MW), access track and infrastructure, switchgear control building, anemometer mast and temporary control compound at land on Skelpick Estate 3 km east south east of Bettyhill Report by Area Planning and Building Standards Manager SUMMARY The application is in detail for the erection of a 2 turbine windfarm on land to the east south east of Bettyhill. The turbines have a maximum hub height of 80m and a maximum height to blade tip of 120m, with an individual output of between 2 – 2.5 MW. In addition a 70m anemometer mast is proposed, with up to 2.9km of access tracks. The site does not lie within any areas designated for their natural heritage interests but does lie close to the: • Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands Special Area of Conservation (SAC) • Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands Special Protection Area (SPA) • Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands RAMSAR site • Lochan Buidhe Mires Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) • Armadale Gorge Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) • Kyle of Tongue National Scenic Area (NSA) Three Community Councils have been consulted on the application. Melvich and Tongue Community Councils have not objected, but Bettyhill, Strathnaver and Altnaharra Community Council has objected. There are 46 timeous letters of representation from members of the public, with 8 non- timeous. The application has been advertised as it has been accompanied by an Environmental Statement (ES), being a development which is classified as ‘an EIA development’ as defined by the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations. -

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

Layout 1 Copy

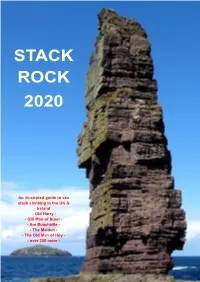

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

Orkney Greylag Goose Survey Report 2015

The abundance and distribution of British Greylag Geese in Orkney, August 2015 A report by the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust to Scottish Natural Heritage Carl Mitchell 1, Alan Leitch 2, & Eric Meek 3 November 2015 1 The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, Gloucester, GL2 7BT 2 The Willows, Finstown, Orkney, KY17, 2EJ 3 Dashwood, 66 Main Street, Alford, Aberdeenshire, AB33 8AA 1 © The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This publication should be cited as: Mitchell, C., A.J. Leitch & E. Meek. 2015. The abundance and distribution of British Greylag Geese in Orkney, August 2015. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Report, Slimbridge. 16pp. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Gloucester GL2 7BT T 01453 891900 F 01453 890827 E [email protected] Reg. Charity no. 1030884 England & Wales, SC039410 Scotland 2 Contents Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Methods ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Field counts ...................................................................................................................................... -

Dornochyou Can Do It All from Here

DornochYou can do it all from here The Highlands in miniature only 2 miles off the NC500 & one hour from Inverness Visit Dornoch, an historic Royal Burgh with a 13th century Cathedral, Castle, Jail & Courthouse in golden sandstone, all nestled round the green and Square where we hold summer markets and the pipe band plays on Saturday evenings. Things to do Historylinks Museum Historylinks Trail Discover 7,000 years of Explore the town through 16 Dornoch’s turbulent past in heritage sites with display our Visit Scotland 5 star panels. Pick up a leaflet and rated museum. map at the museum. Royal Dornoch Golf Club Dornoch Cathedral Golf has been played here for Gilbert de Moravia began over 400 years. building the Cathedral in 1224. The championship course is Following clan feuds it fell into rated #1 in Scotland and #4 in disrepair and was substantially the World by Golf Digest. restored in the 1800s. Aspen Spa Experience Dornoch & Embo Beaches Take some time out and relax Enjoy miles of unspoilt with a luxury spa, beauty beaches - ideal for making treatment or specialist golf sandcastles with the children massage. Gifts, beauty and spa or just walking the dog. products available in the shop. Events Calendar 2019 Car Boot Sales Community Markets The last Saturday of the month The 2nd Wednesday of the February, April, June, August month May to September, also & October fourth Wednesday June, July Dornoch Social Club & August. Cathedral Green 9:30 am - 12:30 pm 9:30 am - 1 pm Fibre Fest 8 - 10- March Dornoch Pipe Band Master classes, learning Parade on most Saturday techniques and drop in evenings from the 25th May to sessions.