Revisiting Francis Birtles' Painted Car: Exploring a Cross-Cultural Encounter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Australian Colonial History a Refereed Journal ISSN 1441-0370

FREE SAMPLE ARTICLE Journal of Australian Colonial History A Refereed Journal ISSN 1441-0370 School of Humanities University of New England Armidale NSW 2351 Australia http://www.une.edu.au/humanities/jach/ Jim Davidson, 'Also Under the Southern Cross: Federation Australia and South Africa — The Boer War and Other Interactions. The 2011 Russel Ward Annual Lecture', Journal of Australian Colonial History, Vol. 14, 2012, pp. 183-204. COPYRIGHT NOTICE This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by the School of humanities of the University of New England. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only for personal, non-commercial use only, for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Enquiries should be made to the Editor. © Editor. Published by the School of Humanities, University of New England, 2012 Also Under the Southern Cross: Federation Australia and South Africa — The Boer War and Other Interactions The 2011 Russel Ward Annual Lecture University of New England, 8 September 2011 Jim Davidson University of Melbourne ussel Ward, amongst various attainments, gave us in The Australian Legend one of Australia's handful of great history Rb ooks. Ward's book was a seminal exploration of the Australian identity. And while linear, progressing from convicts to miners and soldiers (our two varieties of digger), the book was also implicitly lateral; its purpose was largely to differentiate Australians from other English speakers. The Australian Legend was decidedly not a work of tub-thumping nationalism. -

UQFL477 Fryer Library Photograph Collection

FRYER LIBRARY Manuscript Finding Aid UQFL477 Fryer Library Photograph Collection Size 6 boxes, 1 parcel Contents Approximately 900 photographs, mostly black and white, some sepia. Photographs mostly relating to Queensland people and places, but including interstate and overseas photographs. Includes photographs of Australian authors, the 1893 Brisbane floods, and Mornington Island (Queensland). There are also a number of photographs of Papua New Guinea which were originally in the Beazley collection (UQFL271). Other photographs of Queensland people and places can be found in UQFL479. Notes Open access Box 1 Box 2 Box 3 Box 4 Box 5 Box 6 PIC1 – 100 PIC101 – 196 PIC206 – 273 PIC301 – 399 PIC400 – 699 PIC700 – Parcel 1 PIC548; PIC589; PIC709; PIC838; PIC839 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Last updated: 24/11/2020 © University of Queensland 1 FRYER LIBRARY Manuscript Finding Aid Subject PIC Photographer Photograph no. Description Date if known details Notes Wolston House Brisbane Photos of Wolston house taken before 1 restoration 8x6x2cm ; b&w View on the coast of New Holland where the ship was laid ashore in order to repair Endeavour the damage received on the rocks. 7 River, N.S.W. Photograph of sketch by Will Bych n.d. 23x12 cm ; b&w View from Bowen Terrace, 8 Brisbane View from Bowen Terrace, Brisbane 1873 21x16cm ; b&w Propaganda photographs dropped by the Luftwaffe on Australian soldiers who were 2 photos ; 8x6cm 10 World War II defending Tobruk n.d. ; b&w ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Last updated: 24/11/2020 © University of Queensland 2 FRYER LIBRARY Manuscript Finding Aid Subject PIC Photographer Photograph no. Description Date if known details Notes Queensland National Bank, Longreach, Queensland Qld which was officially opened by the National Bank, Bank's Chief Inspector Mr D.S. -

THE QUIET ACHIEVER' BP SOLAR CAR CROSSING of AUSTRALIA Perth to Sydney Sunday 19 December 1982 to Friday 7 January 1983

‘THE QUIET ACHIEVER' BP SOLAR CAR CROSSING OF AUSTRALIA Perth to Sydney Sunday 19 December 1982 to Friday 7 January 1983 'THE LITTLE CAR THAT COULD' Tom Snooks was the Project Coordinator and he has compiled a record of the BP Solar Trek, using press clippings from the day, a video made on the project, monitoring records, and memories. A great shot of The Quiet Achiever traveling through outback New South Wales. 1 THE QUIET ACHIEVER An endurance test, the first of its kind ever held anywhere in the world, occurred in Australia in late 1982/early 1983. It was conducted under the auspices of the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS). This test was the first trans-continental crossing by a solar-powered car, when Hans Tholstrup and Larry Perkins successfully completed the historic BP Solar Trek across Australia, when they brought 'The Quiet Achiever' from Perth to Sydney. They had no overseas technology to draw on, no plans to follow, no previous mistakes to look at or learn from, yet in eight months they designed and built a whole new machine that ran for over 4000 kilometres with only some broken wheel spokes and a number of punctures. They took 20 days to make the crossing, but had all the roads been as smooth after Wilcannia when they covered 307 and 287 kilometres, they could have run the vehicle in high gear and completed the trip in around 14 days. Hans got the idea for the trek in 1980 when the combined pedal and solar powered 'Gossamer' plane flew across the 35 kilometre English Channel. -

Imperial Rhetoric in Travel Literature of Australia 1813-1914. Phd Thesis, James Cook University

This file is part of the following reference: Jensen, Judith A Unpacking the travel writers’ baggage: imperial rhetoric in travel literature of Australia 1813-1914. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/10427 PART THREE: MAINTAINING THE CONNECTION Imperial rhetoric and the literature of travel 1850-1914 Part three examines the imperial rhetoric contained in travel literature in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries which worked to convey an image of Australia’s connection to Britain and the empire. Through a literary approach that employed metaphors of family, travel writers established the perception of Australia’s emotional and psychological ties to Britain and loyalty to the Empire. Contemporary theories about race, the environment and progress provided an intellectual context that founded travel writers’ discussions about Australia and its physical links to Britain. For example, a fear of how degeneration of the Anglo-Saxon race would affect the future of the British Empire provided a background for travellers’ observations of how the Anglo-Saxon race had adapted to the Australian environment. Environmental and biological determinism explained the appearance of Anglo-Australians, native-born Australians and the Australian type. While these descriptions of Australians were not always positive they emphasised the connection of Australians to Britain and the Empire. Fit and healthy Australians equated to a fit and healthy nation and a robust and prestigious empire. Travellers emphasised the importance of Australian women to this objective, as they were the moral guardians of the nation and the progenitors of the ensuing generation. -

The Human Motor: Hubert Opperman and Endurance Cycling in Interwar

The Human Motor: Hubert Opperman and Endurance Cycling in Interwar Australia DANIEL OAKMAN During the late 1920s and 1930s, Hubert ‘Oppy’ Opperman (1904–1996) rose to prominence as the greatest endurance cyclist of the period. After success in Europe, Opperman spent a decade setting a slew of transcontinental and intercity cycling records. This article explores how Opperman attained his celebrity status and why his feats of endurance resonated powerfully with the Australian public. More than a mere distraction in the economic turmoil of the Depression, Opperman’s significance can be explained within the context of broader concerns about modernity, national capacity, efficiency and race patriotism. This article also argues that for a nation insecure about its physical and moral condition, Opperman fostered new understandings of athleticism, masculinity and the capacity of white Australians to thrive in a vast and sparsely populated continent. On the morning of 5 November 1937, the Mayor of Fremantle, Frank Gibson, gently lowered the rear wheel of Hubert Opperman’s bicycle into the Indian Ocean, signalling the start of the famed endurance cyclist’s attempt on the transcontinental cycling record, a distance of some 2,700 miles that he hoped to cover in less than eighteen days.1 Thousands had turned out to see the champion cyclist and he rode leisurely, so that they each might catch a glimpse of his new machine.2 Fascination with the record attempt had been building for weeks. The Melbourne Argus printed a picture of Opperman’s ‘million revolution legs’ on the front page and estimated that with an average pedal pressure of twenty-five pounds, he would need to exert over 1 22,234 tons to cover the distance.3 For the next two weeks, newspaper and radio broadcasts reported on every aspect of the ride, including his gear selection, diet, clothing, sleeping regimes and daily mileages. -

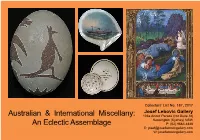

Australian & International Miscellany: an Eclectic Assemblage

Collectors’ List No. 187, 2017 Josef Lebovic Gallery Australian & International Miscellany: 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW An Eclectic Assemblage P: (02) 9663 4848 E: [email protected] W: joseflebovicgallery.com 1.| |The Last Supper And The Agony In The Gar JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY den From “The Book Of Hours”,| c1500.| Tempera Celebrating 40 Years • Established 1977 on vellum, 10.6 x 7.7cm. Slight cockling and paint loss Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) upper and lower left. Framed.| $2,950| The Agony in the Garden refers to the events in the life of Jesus, Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW as recorded in the New Testament, between the Farewell Dis- Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia course at the conclusion of the Last Supper and Jesus’ arrest. Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 “Jesus prays in the Garden of Gethsemane while three of his disciples – Peter, James and John – sleep. An angel reveals Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com a cup and a paten, symbols of his impending sacrifice. In the Open: Monday to Saturday from 1 to 6pm by chance or by appointment background, Judas approaches with the Roman soldiers who will arrest Jesus (New Testament, Mark 14: 32-43).” Ref: The National Gallery, UK; Wiki. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 187, 2017 Australian & International Miscellany: 2.| |The Mutineers Turning Lieut. Bligh And Part Of The Officers And Crew Adrift From His Majesty’s Ship The “Bounty”,| 1790.| Aquatint and engraving, accompanied An Eclectic Assemblage with four related engravings, text including artist, title and date in plate below image, 47 x 63.8cm. -

Bicycles, Cars and Australian Settler Colonialism Georgine W

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2015 Mobile encounters: Bicycles, cars and Australian settler colonialism Georgine W. Clarsen University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Clarsen, G. W. (2015). Mobile encounters: Bicycles, cars and Australian settler colonialism. History Australia, 12 (1), 165-186. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Mobile encounters: Bicycles, cars and Australian settler colonialism Abstract At the turn of the twentieth century bicycles and motorcars constituted a significant break from organic modes of mobility, such as walking, horses and camels. In Australia, such mechanical modes of personal transport were settler imports that generated local meanings and practices as they were integrated into the material, cultural and political conditions of the settler nation-in-the-making. For settlers, new technologies confirmed their racial superiority and reinforced a collective sense of their own modernity. Aboriginal people frequently expressed fear and epistemological confusion when they first encountered the strange vehicles. Contrary to settler investments in Aboriginal people as outside of the contemporary world, however, they soon incorporated bicycles and automobiles into their lives. Aboriginal people complicated that imagined divide between primitivism and modernity as they devised new pleasures, accommodations, resistances and collaborations through those new technologies. Keywords australian, colonialism, cars, mobile, bicycles, settler, encounters Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Clarsen, G. W. (2015). Mobile encounters: Bicycles, cars and Australian settler colonialism. History Australia, 12 (1), 165-186. -

Striving for National Fitness

STRIVING FOR NATIONAL FITNESS EUGENICS IN AUSTRALIA 1910s TO 1930s Diana H Wyndham A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Sydney July 1996 Abstract Striving For National Fitness: Eugenics in Australia, 1910s to 1930s Eugenics movements developed early this century in more than 20 countries, including Australia. However, for many years the vast literature on eugenics focused almost exclusively on the history of eugenics in Britain and America. While some aspects of eugenics in Australia are now being documented, the history of this movement largely remained to be written. Australians experienced both fears and hopes at the time of Federation in 1901. Some feared that the white population was declining and degenerating but they also hoped to create a new utopian society which would outstrip the achievements, and avoid the poverty and industrial unrest, of Britain and America. Some responded to these mixed emotions by combining notions of efficiency and progress with eugenic ideas about maximising the growth of a white population and filling the 'empty spaces'. It was hoped that by taking these actions Australia would avoid 'racial suicide' or Asian invasion and would improve national fitness, thus avoiding 'racial decay' and starting to create a 'paradise of physical perfection'. This thesis considers the impact of eugenics in Australia by examining three related propositions: • that from the 1910s to the 1930s, eugenic ideas in Australia were readily accepted because of concerns about the declining birth rate • that, while mainly derivative, Australian eugenics had several distinctly Australian qualities • that eugenics has a legacy in many disciplines, particularly family planning and public health This examination of Australian eugenics is primarily from the perspective of the people, publications and organisations which contributed to this movement in the first half of this century. -

Bridging the DISTANCE Bridging the DISTANCE

Bridging the DISTANCE Bridging the DISTANCE National Library of Australia Canberra 2008 This catalogue was published on the occasion of the exhibition of Bridging the Distance, which was on display at the National Library of Australia from 6 March to 15 June 2008. The National Library of Australia gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Exhibition Sponsor Published by the National Library of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 © National Library of Australia 2008 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Bridging the distance. ISBN: 9780642276612 (pbk). Bibliography. National Library of Australia—Exhibitions. Telecommunication—Australia—Exhibitions. Rural transportation—Australia—Exhibitions. Transportation—Australia—Exhibitions. Library exhibits—Australian Capital Territory—Canberra. National Library of Australia. 388 Curator: Margaret Dent Curatorial Assistant: Irene Turpie Catalogue text: John Clark and Margaret Dent Editor: Paige Amor Designer: Kathy Jakupec Printed by Nexus Print Solutions Cover image and detail on pages 8 and 9: Frank Hurley (1885–1962) Dirt Road Bordered by Saltbush, Grey Chevrolet in Foreground, Central Australia [between 1955 and 1962] digital print from 35 mm colour transparency, printed 2007 Reproduced courtesy of the Hurley family Contents Foreword v Jan Fullerton The Question of Distance 1 Selected Items from the Exhibition Eugene von Guérard’s Natives Chasing Game 10 S.T. Gill, Watercolourist 12 Ancestor Track Map 15 William John Wills, Explorer 16 Ernest Giles, Explorer 18 Edward John Eyre, Explorer 21 Brother Edward Kempe’s Album 22 The First Inland Settlement: Bathurst, New South Wales 24 Harry Sandeman, ‘Gone Out to Australia’ 26 Cobb and Co. 28 Swaggies 31 Camels, the ‘Ships of the Desert’ 32 George French Angas, Naturalist and Artist 34 Riverboats 36 Samuel Sweet, Photographer 39 Building a Railway 40 The Car in Australia 42 Roads and Highways 45 The Royal Flying Doctor Service 46 Balarinji Jets for Qantas 48 Exhibition Checklist 51 Select Bibliography 60 M. -

Things: Photographing the Constructed World 24 November 2012–17 February 2013

Things: Photographing the Constructed World 24 November 2012–17 February 2013 Introduction Unknown photographer Man holding up unidentified object tied with rope c. 1925 gelatin silver print; 13.5 x 18.5 cm Hermann J. Asmus collection, Asia and Australia Pictures Collection, nla.pic-vn6055296 Unknown photographer James Barrie, surveyor, sharebroker and commission agent, with his surveying equipment, staff and a girl, possibly from the Ellis family, outside Barrie’s weatherboard office, Tambaroora Street, Hill End, New South Wales 1872 or 1873 In album: Album of photographs of gold mining, buildings, residents and views at Hill End and environs, New South Wales, 1872–1873 albumen silver print; 6.0 x 10.0 cm B.O. Holtermann archive of Merlin and Bayliss photographic prints of New South Wales and Victoria, 1872–1888 Pictures Collection, nla.pic-vn4735617 Charles Bayliss (1850–1897) Five unidentified surveyors at camp site, New South Wales between 1880 and 1897 From album: New South Wales photographs, 1880–1900 albumen silver print; 14.8 x 19.3 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an24616998 Australian Department of Home Affairs, Lands and Surveys Branch Portrait of Federal Capital site surveyors, four seated and two standing, Camp Hill, Canberra 1910 In album: Photographs of the federal capital site, 1909–1910 gelatin silver print; 26.5 x 35.5 cm Page 1 of 47 Pictures Collection, nla.pic-vn4599805 Attributed to Iris Spinks Ken’s survey boys 1936 From album: Ken and Iris Spinks’ collection of photographs Central New Guinea, 1933–1936 gelatin silver -

Frank Briggs - a Forgotten Flyer Remembered by Chas Schaedel

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN AVIATION MUSEUM SIGNIFICANT AVIATOR PROFILES FRANK BRIGGS - A FORGOTTEN FLYER REMEMBERED BY CHAS SCHAEDEL In November-December 1919 the Australian continent was first traversed by air when Captain H. N. Wrigley and Sergeant A. W. Murphy flew a wartime-designed BE2e from south to north. Members of the embryo Australian air force that replaced the disbanded Australian Flying Corps after the First World War, they had a couple of false starts before they left Melbourne on 16th November, but after covering 4,000 kilometres in 46 flying Frank Briggs in the cockpit of a DH9 during his hours they touched down in RFC/RAF career in the First World War Darwin on 12th December. [David Vincent] This was two days after Ross and Keith Smith with mechanics Bennett and Shiers completed the first flight from England, so Wrigley and Murphy were not on hand to greet the crew of the Vickers Vimy as planned. They suffered a further setback when their superiors refused to let them fly back to Melbourne and made them dismantle the BE2e for return by land transport. Bypassing Brisbane, the Smith brothers then flew from the north to the south of Australia in stages via Sydney and Melbourne, until they reached their home city of Adelaide on 23rd March 1920. In November-December 1920 the Australian continent was flown over in an east-west direction for the first time, when F. S. Briggs flew C. J. de Garis and mechanic O. J. Howard on a round trip Melbourne-Perth-Sydney-Melbourne in a De Havilland 4 aeroplane. -

Bridging the DISTANCE Bridging the DISTANCE

Bridging the DISTANCE Bridging the DISTANCE National Library of Australia Canberra 2008 This catalogue was published on the occasion of the exhibition of Bridging the Distance, which was on display at the National Library of Australia from 6 March to 15 June 2008. The National Library of Australia gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Exhibition Sponsor Published by the National Library of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 © National Library of Australia 2008 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Bridging the distance. ISBN: 9780642276612 (pbk). Bibliography. National Library of Australia—Exhibitions. Telecommunication—Australia—Exhibitions. Rural transportation—Australia—Exhibitions. Transportation—Australia—Exhibitions. Library exhibits—Australian Capital Territory—Canberra. National Library of Australia. 388 Curator: Margaret Dent Curatorial Assistant: Irene Turpie Catalogue text: John Clark and Margaret Dent Editor: Paige Amor Designer: Kathy Jakupec Printed by Nexus Print Solutions Cover image and detail on pages 8 and 9: Frank Hurley (1885–1962) Dirt Road Bordered by Saltbush, Grey Chevrolet in Foreground, Central Australia [between 1955 and 1962] digital print from 35 mm colour transparency, printed 2007 Reproduced courtesy of the Hurley family Contents Foreword v Jan Fullerton The Question of Distance 1 Selected Items from the Exhibition Eugene von Guérard’s Natives Chasing Game 10 S.T. Gill, Watercolourist 12 Ancestor Track Map 15 William John Wills, Explorer 16 Ernest Giles, Explorer 18 Edward John Eyre, Explorer 21 Brother Edward Kempe’s Album 22 The First Inland Settlement: Bathurst, New South Wales 24 Harry Sandeman, ‘Gone Out to Australia’ 26 Cobb and Co. 28 Swaggies 31 Camels, the ‘Ships of the Desert’ 32 George French Angas, Naturalist and Artist 34 Riverboats 36 Samuel Sweet, Photographer 39 Building a Railway 40 The Car in Australia 42 Roads and Highways 45 The Royal Flying Doctor Service 46 Balarinji Jets for Qantas 48 Exhibition Checklist 51 Select Bibliography 60 M.