Not for Citation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Online Shop Offers Outlet Nike Football Jersey,Authentic New Nike Jerseys,Nfl Kids Jersey,China Wholesale Cheap Football

Our online shop offers Outlet Nike Football Jersey,Authentic new nike jerseys,nfl kids jersey,China wholesale cheap football jersey,Cheap NHL Jerseys.Cheap price and good quality,IF you want to buy good jerseys,click here!ANAHEIM ?a If you see by the pure numbers,nfl stitched jerseys, Peter Holland??s fourth season surrounded the Ontario Hockey League didn?¡¥t characterize a drastic amendment from his third. Look beyond the numbers and you?¡¥ll find that?the 20-year-old center?took a significant step ahead. Holland amended his goal absolute with the Guelph Storm from 30 to 37 and his digit of points?from 79 to 88. The improvements are modest merely it is the manner he went almost it that has folk seeing him in a different light. The lack of consistency among his game has hung around Holland?¡¥s neck among junior hockey and the Ducks?¡¥ altitude elect surrounded 2009 was cognizant enough to acquaint that his converge prior to last season. ?¡ãThat?¡¥s kind of been flagged about me as the past pair of years immediately,nike new nfl jerseys,nfl custom jerseys,?¡À Holland said.??¡ÀObviously you go aboard the things that folk tell you to go on so I was trying to go on my consistency. I thought I did smart well this daily.?¡À ?¡ãThat comes with maturity also Being capable to activity the same game every night. It?¡¥s never a matter of being a 120 percent an night and 80 percen the?next. It?¡¥s almost being consistent at that 95-100 percent region.?¡À Looking after Holland said spending another season surrounded Guelph certified beneficial The long stretches where he went without points shrank to a minimum. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 03/05/19 Anaheim Ducks Dallas Stars 1134363 Up next for the Ducks: Tuesday at Arizona 1134399 Stars 2019 playoff tracker: Where Dallas sits in the 1134364 Ducks’ Ryan Kesler about to hit a grand milestone by Western Conference standings (updated daily) playing 1,000th game 1134400 National writer ranks two skaters above Stars' Miro 1134365 Ducks Film Room: Anaheim’s future success hinges on Heiskanen on list of NHL's top rookies this season development of Steel, Terry and Jones 1134401 Stars forward Andrew Cogliano nears end of first injury- induced absence of career: 'These are the games you wa Arizona Coyotes 1134402 Shap Shots: Making sense of Montgomery’s Process, 1134367 How will Jason Demers fit back into the Coyotes' lineup? Fiddler on faceoffs, and shootouts 1134368 NHL Western Conference Wild Card tracker: Coyotes making playoff push Detroit Red Wings 1134369 Coyotes players handled differently: A case study in 1134403 Detroit Red Wings' Ted Lindsay funeral: Public visitation coaching Friday at LCA 1134404 Detroit Red Wings greats on what made Ted Lindsay Boston Bruins memorable across decades 1134370 Bruins’ goal is simple: Keep this roll going 1134405 How one picture captured who Ted Lindsay was to Detroit 1134371 Bruins’ Jake DeBrusk puts goal drought in past Red Wings 1134372 Bruins notebook: Confidence soars during points streak 1134406 Ted Lindsay created one of the best traditions in sports 1134373 Kevan Miller downgraded to "week-to-week" with injury history after "bad news" MRI 1134407 Ted -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUNE 10, 2021 Mackinnon, MATTHEWS and Mcdavid VOTED HART TROPHY FINALISTS NEW YORK

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUNE 10, 2021 MacKINNON, MATTHEWS AND McDAVID VOTED HART TROPHY FINALISTS NEW YORK (June 10, 2021) – Colorado Avalanche center Nathan MacKinnon, Toronto Maple Leafs center Auston Matthews and Edmonton Oilers center Connor McDavid are the three finalists for the 2020-21 Hart Memorial Trophy, awarded “to the player adjudged to be the most valuable to his team,” the National Hockey League announced today. Members of the Professional Hockey Writers Association submitted ballots for the Hart Trophy at the conclusion of the regular season, with the top three vote-getters designated as finalists. The winners of the 2021 NHL Awards presented by Bridgestone will be revealed during the Stanley Cup Semifinals and Stanley Cup Final, with exact dates, format and times to be announced. Following are the finalists for the Hart Trophy, in alphabetical order: Nathan MacKinnon, C, Colorado Avalanche MacKinnon placed fourth in the NHL with a career-high 1.35 points per game (20-45—65 in 48 GP) to propel the Avalanche’s top-ranked offense to the franchise’s third Presidents’ Trophy (also 1996-97 and 2000-01). MacKinnon finished among the League leaders in shots on goal (3rd; 206), power-play points (3rd; 25), assists (5th; 45), points (8th; 65) and power-play assists (t-10th; 17) despite missing eight of Colorado’s 56 contests. He did so on the strength of a career-best 15-game point streak from March 27 – April 28 (9-17—26), the longest by any player in 2020-21 as well as the longest by a member of the Avalanche since 2006-07 (Paul Stastny: 20 GP). -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

2017-18 Leaf Stickwork Hockey Player Checklist 177 Players with Cards 141 Players with 21+ Cards; 36 Players with 5 Or Less Cards

2017-18 Leaf Stickwork Hockey Player Checklist 177 Players with Cards 141 Players with 21+ Cards; 36 Players with 5 or less Cards Player Set Card # Print Run Adam Foote Nameplates N-01 1 Adam Oates Game Used Stick GS-01 33 Adam Oates Super Sticks of the 90s 8 Player SSY-10 35 Adam Oates Team Twigs 8 Player TT-04 33 Al Secord Sticks and Stones SS-01 39 Alex Delvecchio Game Used Stick GS-02 33 Alex Delvecchio Nameplates N-03 1 Alex Delvecchio Super Sticks of the 50s 8 Player SSY-01 35 Alex Delvecchio Titans of Timber 6 Player TOT-07 35 Alexander Mogilny Signature Sticks 2 Dual Player SSD-01 27 Alexander Ovechkin Game Used Stick GS-03 33 Alexander Ovechkin Nameplates N-04 1 Alexander Ovechkin Stick Rack 3 Triple Player SR3-05 31 Allan Stanley Lumbergraphs LG-02 1 Allan Stanley Super Sticks of the 60s 8 Player SSY-04 35 André Dupont Nameplates N-05 1 Andre Lacroix Game Used Stick GS-04 33 Andre Lacroix Super Sticks of the 70s 8 Player SSY-06 35 Andy Bathgate Game Used Stick GS-05 30 Andy Bathgate Tape 8 Player T8-05 30 Andy Moog Game Used Goalie Stick GGS-01 32 Bernie Federko Game Used Stick GS-06 33 Bernie Federko Titans of Timber 6 Player TOT-05 35 Bernie Geoffrion Game Used Stick GS-07 30 Bernie Geoffrion Nameplates N-06 1 Bernie Geoffrion Stick Rack 4 Quad Player SR4-11 35 Bernie Geoffrion Super Blade SB-BF1 10 Bernie Geoffrion Super Sticks of the 50s 8 Player SSY-01 35 Bernie Geoffrion Super Sticks of the 50s 8 Player SSY-02 35 Bernie Geoffrion Titans of Timber 6 Player TOT-07 35 groupbreakchecklists.com 2017-18 Leaf Stickwork Hockey -

Annex of Visual Documents and Links for LES “Who Controls the Puck” Please Respect Individual Image and Website Licensing C

Annex of visual documents and links for LES “Who Controls the Puck” Please respect individual image and website licensing conditions, which vary depending on each source. NHL Hockey in the 1950s Their feeder system, which supplied all but a tiny percentage of talent to the NHL six, consisted of junior teams spread coast to coast across Canada, all of which were controlled – and sometimes wholly owned – by the major league clubs. The major league's control often reached down into the pee- wee leagues, so if a talented young player began serious competitive play for an affiliate of the Bruins, Maple Leafs or one of the others, he would remain the property of that organization until they traded or released him. With so much talent stockpiled in so few farm systems, the pay scales could be easily controlled, too. It wasn't quite cradle-to-grave ownership, but it was close. Nowhere was the stamp of the parent team Winnipeg Warriors, 1955-56, ! more traditional than in the Province of Quebec, champions of the Western Hockey League! and farm team for the Canadians that same year!! where boys of French-Canadian heritage yearned to ! be happy serfs of the Canadiens. Information source for Canadien farm teams:! http://www.hockeydb.com/ihdb/stats/display_affiliations_parent.php?tmi=6929! Image source: Western Canada Pictorial Index! More information at Manitoba Historical at! Source: Larry Felsner, cited in Habs Eye on the Prize available: http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/27/businessofhockey.shtml! http://www.habseyesontheprize.com/2010/3/17/1377048/the-rocket-richard- ! riot-55-years ! Riots after Richard Suspended !! During the 1950’s Maurice “Rocket” Richard was the most dynamic hockey player in the National Hockey League. -

AN HONOURED PAST... and Bright Future an HONOURED PAST

2012 Induction Saturday, June 16, 2012 Convention Hall, Conexus Arts Centre, 200 Lakeshore Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan AN HONOURED PAST... and bright future AN HONOURED PAST... and bright future 2012 Induction Saturday, June 16, 2012 Convention Hall , Conexus Arts Centre, 200 Lakeshore Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan INDUCTION PROGRAM THE SASKATCHEWAN Master of Ceremonies: SPORTS HALL OF FAME Rod Pedersen 2011-12 Parade of Inductees BOARD OF DIRECTORS President: Hugh Vassos INDUCTION CEREMONY Vice President: Trent Fraser Treasurer: Reid Mossing Fiona Smith-Bell - Hockey Secretary: Scott Waters Don Clark - Wrestling Past President: Paul Spasoff Orland Kurtenbach - Hockey DIRECTORS: Darcey Busse - Volleyball Linda Burnham Judy Peddle - Athletics Steve Chisholm Donna Veale - Softball Jim Dundas Karin Lofstrom - Multi Sport Brooks Findlay Greg Indzeoski Vanessa Monar Enweani - Athletics Shirley Kowalski 2007 Saskatchewan Roughrider Football Team Scott MacQuarrie Michael Mintenko - Swimming Vance McNab Nomination Process Inductee Eligibility is as follows: ATHLETE: * Nominees must have represented sport with distinction in athletic competition; both in Saskatchewan and outside the province; or whose example has brought great credit to the sport and high respect for the individual; and whose conduct will not bring discredit to the SSHF. * Nominees must have compiled an outstanding record in one or more sports. * Nominees must be individuals with substantial connections to Saskatchewan. * Nominees do not have to be first recognized by a local satellite hall of fame, if available. * The Junior level of competition will be the minimum level of accomplishment considered for eligibility. * Regardless of age, if an individual competes in an open competition, a nomination will be considered. * Generally speaking, athletes will not be inducted for at least three (3) years after they have finished competing (retired). -

Buffalo Sabres Game Notes

Buffalo Sabres Game Notes Thu, Mar 28, 2019 NHL Game #1189 Buffalo Sabres 31 - 36 - 9 (71 pts) Detroit Red Wings 28 - 38 - 10 (66 pts) Team Game: 77 20 - 13 - 4 (Home) Team Game: 77 14 - 18 - 5 (Home) Home Game: 38 11 - 23 - 5 (Road) Road Game: 40 14 - 20 - 5 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 35 Linus Ullmark 34 14 13 4 3.09 .906 35 Jimmy Howard 49 20 20 5 3.02 .908 40 Carter Hutton 47 17 23 5 2.98 .909 45 Jonathan Bernier 34 8 18 5 3.23 .902 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 4 D Zach Bogosian 65 3 16 19 -5 52 8 L Justin Abdelkader 71 6 13 19 -14 38 6 D Marco Scandella 61 5 7 12 -14 26 17 D Filip Hronek 40 3 13 16 -10 30 8 D Casey Nelson 32 1 4 5 2 13 20 D Dylan McIlrath 1 0 0 0 1 2 9 C Jack Eichel 71 26 49 75 -11 24 25 D Mike Green 43 5 21 26 -1 28 17 C Vladimir Sobotka 68 5 8 13 -19 26 26 L Thomas Vanek 64 16 20 36 -12 26 19 D Jake McCabe 55 4 10 14 -7 35 27 C Michael Rasmussen 62 8 10 18 -8 29 20 L Scott Wilson 10 0 2 2 -4 4 28 R Luke Witkowski 28 0 2 2 -3 16 21 R Kyle Okposo 72 11 14 25 -12 41 39 R Anthony Mantha 61 19 17 36 -14 28 22 C Johan Larsson 67 6 7 13 -7 35 41 C Luke Glendening 76 10 13 23 2 15 23 C Sam Reinhart 76 20 41 61 -9 14 42 R Martin Frk 25 1 4 5 -7 2 24 D Lawrence Pilut 27 1 5 6 -5 18 43 L Darren Helm 55 7 9 16 -12 18 26 D Rasmus Dahlin 76 8 33 41 -9 30 51 C Frans Nielsen 71 10 25 35 -7 14 28 C Zemgus Girgensons 67 4 12 16 -9 13 52 D Jonathan Ericsson 51 3 2 5 -10 35 29 R Jason Pominville 68 15 13 28 -5 4 53 L Taro Hirose 4 0 4 4 0 0 33 D William Borgen 1 0 0 0 0 0 -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 9/10/2020 Boston Bruins Los Angeles Kings 1178657 Bruins’ Bruce Cassidy wins NHL Coach of the Year 1178686 IMPORTANCE OF LOANING PLAYERS TO EUROPEAN honors CLUBS 1178658 NHL has yet to nail down dates for the draft and free agency Minnesota Wild 1178659 Bruins GM Don Sweeney does not sound hopeful about 1178687 Led by Minnesota, influence of college hockey keeps re-signing Torey Krug growing in NHL 1178660 GM Don Sweeney isn’t concerned about Tuukka Rask’s 1178688 Wild offseason update: End of an era for Mikko Koivu? future with the Bruins Plus, trade/buyout banter 1178661 Bruce Cassidy captures Jack Adams Award 1178662 Charlie McAvoy hoping to add more pop Montreal Canadiens 1178663 Sweeney knows B's have to make some changes 1178689 Stu on Sports: A flashback to last year's Canadiens golf 1178664 Sweeney says B's have 'zero reservations' about Rask tournament moving forward 1178665 Bruins' Bruce Cassidy wins 2020 Jack Adams Award Nashville Predators 1178666 For guiding Bruins’ regular season rebound, Bruce 1178690 Source: Dan Hinote expected to join Predators as Cassidy wins Jack Adams Award assistant coach 1178667 Trade winds? Bruins are all ears prior to free agency 1178668 Agent: No talks from Tuukka Rask on an early retirement New Jersey Devils 1178691 7 takeaways from Devils hiring Mark Recchi to assist Buffalo Sabres Lindy Ruff | ‘I’m not a yes man!’ 1178669 Sabres' goaltending prospects face challenging 1178692 How new assistant coach Mark Recchi can help the Devils development curve rebound 1178670 NHL reportedly sets dates for entry draft, start of free agency New York Islanders 1178671 2020 NHL organizational rankings: No. -

1934 SC Playoff Summaries

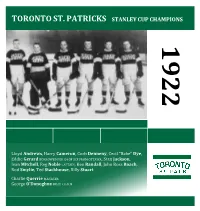

TORONTO ST. PATRICKS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 192 2 Lloyd Andrews, Harry Cameron, Corb Denneny, Cecil “Babe” Dye, Eddie Gerard BORROWED FOR G4 OF SCF FROM OTTAWA, Stan Jackson, Ivan Mitchell, Reg Noble CAPTAIN, Ken Randall, John Ross Roach, Rod Smylie, Ted Stackhouse, Billy Stuart Charlie Querrie MANAGER George O’Donoghue HEAD COACH 1922 NHL FINAL OTTAWA SENATORS 30 v. TORONTO ST. PATRICKS 27 GM TOMMY GORMAN, HC PETE GREEN v. GM CHARLIE QUERRIE, HC GEORGE O’DONOGHUE ST. PATRICKS WIN SERIES 5 GOALS TO 4 Saturday, March 11 Monday, March 13 OTTAWA 4 @ TORONTO 5 TORONTO 0 @ OTTAWA 0 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. TORONTO, Ken Randall 0:30 NO SCORING 2. TORONTO, Billy Stuart 2:05 3. OTTAWA, Frank Nighbor 6:05 SECOND PERIOD 4. OTTAWA, Cy Denneny 7:05 NO SCORING 5. OTTAWA, Cy Denneny 11:00 THIRD PERIOD SECOND PERIOD NO SCORING 6. TORONTO, Babe Dye 3:50 7. OTTAWA, Frank Nighbor 6:20 Game Penalties — Cameron T 3, Corb Denneny T, Clancy O, Gerard O, Noble T, F. Boucher O 2, Smylie T 8. TORONTO, Babe Dye 6:50 GOALTENDERS — SENATORS, Clint Benedict; ST. PATRICKS, John Ross Roach THIRD PERIOD 9. TORONTO, Corb Denneny 15:00 GWG Officials: Cooper Smeaton At The Arena, Ottawa Game Penalties — Broadbent O 3, Noble T 3, Randall T 2, Dye T, Nighbor O, Cameron T, Cy Denneny O, Gerard O GOALTENDERS — SENATORS, Clint Benedict; ST. PATRICKS, John Ross Roach Official: Cooper Smeaton 8 000 at Arena Gardens © Steve Lansky 2014 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. -

Induction Spotlight Tsn/Rds Broadcast Zone Recent Acquisitions

HOCKEY HALL of FAME NEWS and EVENTS JOURNAL INDUCTION SPOTLIGHT TSN/RDS BROADCAST ZONE RECENT ACQUISITIONS SPRING 2015 CORPORATE MATTERS LETTER FROM THE INDUCTION 2015 • The annual elections meeting of the Selection Committee VICe-CHAIR will be held in Toronto on June 28 & 29, 2015 (with the announcement of the 2015 inductees on June 29th). Dear Teammates: • The Hockey Hall of Fame Induction Celebration will be held on Monday, November 9, 2015. Not long after another successful Graig Abel/HHOF Induction Celebration last November, the closely knit hockey community mourned the loss of two of ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING the game’s most accomplished and respected individuals in Pat • Scotty Bowman, David Branch, Brian Burke, Marc de Foy, Mike Gartner and Anders Quinn and Jean Beliveau. I have been privileged to get to know Hedberg were re-appointed each to a further term on the Selection Committee for the and work with these distinguished gentlemen throughout my 2015, 2016 and 2017 selection proceedings. life in hockey and like many others I was particularly heartened • The general voting Members ratified new By-law Nos. 25 and 26 which, among other by the outstanding tributes that spoke volumes to their impact amendments, provide for improved voting procedures applicable to all categories of on our great sport. Honoured Membership (visit HHOF.com for full transcripts). Although Chair of the Board for little more than a year, Pat left his mark on the Hockey Hall of Fame, overseeing the recruitment BOARD OF DIRECTORS Nominated by: of new members to the Selection Committee, initiating the Lanny McDonald, Chair (1) Corporate Governance Committee first comprehensive selection process review which led to Jim Gregory, Vice-Chair National Hockey League several by-law amendments, and establishing new and renewed Murray Costello Corporate Governance Committee partnerships.