Bulgarian Chess Player Cheating Borislav Ivanov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

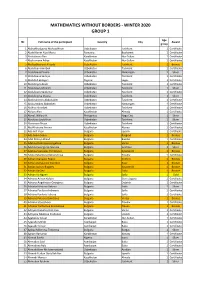

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abboskhodjaeva Mohasalkhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 2 Abdel Karim Alya Maria Romania Bucharest 1 Certificate 3 Abdraimov Alan Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 1 Certificate 4 Abdraimova Adiya Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 1 Certificate 5 Abdujabborova Alizoda Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 6 Abdullaev Amirbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 7 Abdullaeva Dinara Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Silver 8 Abdullaeva Samiya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 9 Abdullah Balogun Nigeria Lagos 1 Certificate 10 Abdullayev Azam Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 11 Abdullayev Mirolim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 12 Abdullayev Saidumar Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 13 Abdullayeva Diyora Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 14 Abdurahimov Abduhakim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 15 Abduvosidov Abbosbek Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Certificate 16 Abidov Islombek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 17 Abiyev Alan Kazakhstan Almaty 1 Certificate 18 Abriol, Willary A. Philippines Naga City 1 Silver 19 Abrolova Laylokhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 20 Abrorova Afruza Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 21 Abulkhairova Amina Kazakhstan Atyrau 1 Certificate 22 Ada Arif Vasvi Bulgaria Isperih 1 Certificate 23 Ada Selim Selim Bulgaria Razgrad 1 Bronze 24 Adel Dzheyn Brand Bulgaria Bansko 1 Certificate 25 Adelina Dobrinova Angelova Bulgaria Varna 1 Bronze 26 Adelina Georgieva Ivanova Bulgaria Svishtov 1 Silver 27 Adelina Svetoslav Yordanova Bulgaria Kyustendil 1 Bronze 28 Adina Zaharieva -

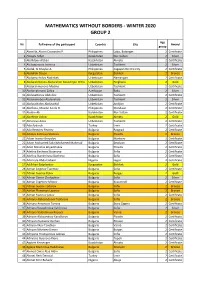

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 2 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abanilla, Alaina Cassandra P. Philippines Lobo, Batangas 2 Certificate 2 Abayev Aidyn Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Silver 3 Abdildaev Alzhan Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Certificate 4 Abduazimova Jasmina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 5 Abdul, Al Khaylar A. Philippines Cagayan De Oro City 2 Certificate 6 Abdullah Dayan Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 2 Bronze 7 Abdumazhidov Nodirbek Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 8 Abdurahmonov Abdurahim Boxodirjon O'G'Li Uzbekistan Ferghana 2 Gold 9 Abdurahmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 10 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 2 Silver 11 Abdusattorov Abdullox Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 12 Abduvahobov Abduvahob Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 13 Abduvohidov Abduvohid Uzbekistan Andijon 2 Certificate 14 Abellana, Maxine Anela O. Philippines Mandaue 2 Certificate 15 Abildin Ali Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Certificate 16 Abirkhan Adina Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Gold 17 Abrorova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 18 Ada Aydınok Turkey Izmir 2 Certificate 19 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 20 Adaliya Kalinova Stoilova Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Bronze 21 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 2 Certificate 22 Adam Mohamed Sabri Mohamed Mahmud Bulgaria Smolyan 2 Certificate 23 Adeli Nikolova Boyadzhieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 24 Adelina Encheva Stoianova Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 25 Adelina Stanimirova Docheva Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 26 Adenrele Abdul Jabaar Nigeria Lagos 2 Certificate -

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 5

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 5 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abareles, En Boyle Miguel O. Philippines Roxas City, Capiz 5 Certificate 2 Abdao, Djiren Riel Loneza Philippines Taguig 5 Certificate 3 Abdigali Beksultan Kazakhstan Almaty 5 Certificate 4 Abdolla Mansur Kazakhstan Almaty 5 Bronze 5 Abdulla Ismatulla Kazakhstan Almaty 5 Certificate 6 Abdullayev Jan Azerbaijan Baku 5 Bronze 7 Abdulrahman Bashirat Nigeria Kaduna 5 Certificate 8 Abdurahmanov Imomnazar Uzbekistan Namangan 5 Certificate 9 Abdymomyn Zhanseit Nurzhauuly Kazakhstan Zhambyl Region, Merke Village 5 Certificate 10 Aben Sanzhanna Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 5 Certificate 11 Abzalbek Ali Kazakhstan Almaty 5 Silver 12 Adeboye Mubaraq Nigeria Lagos 5 Certificate 13 Adel Kassem Kazakhstan Atyrau 5 Certificate 14 Adinay Almazova Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 5 Bronze 15 Adrian Anatoliev Dimitrov Bulgaria Varna 5 Certificate 16 Aduna, Sofia Brea Abad Philippines Mandaluyong 5 Certificate 17 Afanasyev Stepan Kazakhstan Almaty 5 Bronze 18 Aflatunov Adnan Kazakhstan Zhambyl Region, Merke Village 5 Certificate 19 Africa, Ma. Samantha Elisse P. Philippines Tanauan, Batangas 5 Certificate 20 Agabek Askar Kazakhstan Almaty 5 Certificate 21 Agabek Zhomart Kazakhstan Almaty 5 Bronze 22 Agito, Sofia D. Philippines Manila 5 Certificate 23 Aguirre, Ben Matthew H. Philippines Naga City 5 Certificate 24 Aguirre, Josef Nash De Las Alas Philippines San Pedro, Laguna 5 Bronze 25 Ahmet Emir Ozyurt Turkey Izmir 5 Silver 26 Aimukatov Nurkhan Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan -

Bi-Weekly Bulletin 17-30 March 2020

INTEGRITY IN SPORT Bi-weekly Bulletin 17-30 March 2020 Photos International Olympic Committee INTERPOL is not responsible for the content of these articles. The opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not represent the views of INTERPOL or its employees. INTERPOL Integrity in Sport Bi-Weekly Bulletin 17-30 March 2020 INVESTIGATIONS Pakistan PCB Charges Umar Akmal for Breaching Anti-Corruption Code Controversial Pakistan batsman Umar Akmal has been charged on Friday for two separate breaches of the Pakistan Cricket Board's Anti-Corruption Code. Umar, who was provisionally suspended on February 20 and barred from playing for his franchise, Quetta Gladiators in the Pakistan Super League, has been charged for failing to disclose corrupt approaches to the PCB Vigilance and Security Department (without unnecessary delay). If found guilty, Akmal could be banned from all forms of cricket for anywhere between six months and life. He was issued the charge sheet on March 17 and has been given time to respond until March 31. This was a breach under 2.4.4 for PCB's anti- corruption code. A Troubled Career Umar, 29, has had a chequered career since making his debut in August, 2009 and has since just managed to play 16 Tests, 121 ODIs and 84 T20 internationals for his country despite making a century on Test debut. His last appearance came in last October during a home T20 series against Sri Lanka and before that he also played in the March- April, 2019 one-day series against Australia in the UAE. -

NEWSLETTER 118 (May 27, 2013)

NEWSLETTER 118 (May 27, 2013) MR. SERZH SARGSYAN RE-ELECTED PRESIDENT OF THE ARMENIAN CHESS FEDERATION The President of the Republic of Armenia Mr. Serzh Sargsyan was re-elected as President of the Armenian Chess Federation. The elections of the federation’s governing bodies were held on 18th May, 2013 at the Chess House Tigran Petrosian in Yerevan during Conference of the Armenian Chess Federation. The conference summarized the work of the federation within the previous two years. The ECU President Silvio Danailov congratulated Mr. Sargsyan on his re-election. 20th May, 2013 To: His Excellency Mr. Serzh Sargsyan President of Armenian Chess Federation Dear Mr. Sargsyan, Allow me to extend my warmest and heartfelt congratulations on your re-election as President of the Armenian Chess Federation. © Ecuonline.net Page 1 I believe that your re-election comes as a recognition of the outstanding achievements you have made in popularising and promoting chess in your country, making Armenia one of the chess-leading countries in the world, and a reward for your earnest efforts to assist in numerous ways the development and improvement of the game of chess. It is my hope that your new term will provide an opportunity to further strengthen the cordial and friendly relations between the Armenian Chess Federation and the European Chess Union while continuing to work positively and cooperatively towards the common goals of chess promotion and development in Europe and worldwide. The European Chess Union and myself once more send you our best wishes for continued great success in your duties. Yours respectfully, Silvio Danailov ECU President Official website: www.chessfed.am WEBSITE OF THE OFFICIAL ECU TOURIST AGENCY AVAsa STARTS WORKING WWW.ECUTRAVEL.NET It is our pleasure to inform you that the website of the official tourist agency of the European Chess Union AVAsa has started working. -

Abcs of Chess

FineLine Technologies JN Index 80% 1.5 BWR PU JUNE 06 7 25274 64631 9 IFC_Layout 1 5/7/2014 4:30 PM Page 1 What’s New in the USCF Sales’ Library? Diamond Dutch The Panov - Botvinnik Attack - Move by Move NEW! B0139NIC $29.95 B0383EM $27.95 The widely-played Dutch Defence is a sharp choice. Black does not try to The Panov-Botvinnik Attack is an aggressive and ambitious way of meeting preserve a positional balance, but chooses to ght it out.Evgeny But this is no Sveshnikov the popular Caro-Kann Defence.256 White pages develops -rapidly $29.95 and attacks the centre, ordinary repertoire book - it covers the entire spectrum for White as well as putting immediate pressure on Black's position. This book provides an Black, including various Anti-Dutch weapons, the Stonewall System, the in-depth look at the Panov-Botvinnik Attack and also the closely related 2.c4 Classical System and Leningrad System. This book will certainly shake up variation. Using illustrative games, D'Costa highlights the typical plans and the lines of the Dutch Defense! tactics for both sides, presents repertoire options for White and provides answers to all the key questions. The Extreme Caro-Kann 1001 Winning Chess Sacrices and B0140NIC developments$28.95 and presentsCombinations a number of cunning new ideas, many of which come from his The Caro-Kann Defence has become one of the most important and popular B0072RE $19.95 replies to 1.e4. Its ‘solid’ and ‘drawish’ reputation no longer applies in modern 21st Century Edition of a Timeless Classic - Now in Algebraic Notation! This chess. -

Tidskrift För

Landslagsspelare som valde livet före schacket Stockholms SS 150 år Det visste du inte om schack & film Ralf Åkesson rockar loss on the Rock Nr 1 l 2016 TIDSKRIFT FÖR TEMA FUSK. Historik. Intervju med en fuskare. Tidskrift för Schack INNEHÅLL # 1 – 2016 FUSK VART TOG DE VÄGEN? Öppenhjärtlig Konstanty Kaiszauri sökte känslan av intervju med tysken att nudda det absoluta. Sedan la han av. Christoph Schmid, 25 år senare vågar han fort- som aldrig avslöjades farande inte ta fram pjäserna. 8 trots att han togs på bar gärning. En historisk odyssé – först ut var en skandinav – och till sist fem tips till den som är sugen. SCHACK & FILM 12 fusksidor! Filmvetaren Fredrik Söderlund om krigs föring och sköra psyken. SCHACKJAKTEN 16 46 Av Christer Fuglesang & Jesper Hall 4 Ledare STORMÄSTAREN 5 Mragel Ralf Åkesson tog sin 6 En passant främsta skalp någon sin I Schackj akten får vi följa med syskonen 42 Schack på Expressen-TV när han slog Arkadij Markus och Mairana när de beger sig bak 44 Boknytt Naiditsch i Gibraltar. åt i tiden och på ett spännande och annor Guldgruvan Leonid Stein lunda sätt undersöker schackets uppkomst och historia. AVBROTT SIDA 28 Utöver den spännande resan ger bok 53 Damschack: Cajsa Lindberg UNGDOMSSIDORNA en en introduktion till schackspelandets 54 Skolschack Linnea Johansson Öhman, konst, en skola från första draget till Brunnsängskolan & EU-parlamentet Rilton och listan över vilka schackmatt. 58 Schackhistoriska strövtåg juniorer som spelar mest. 61 GP i GP Alla royalties går till Svenska schack Kombinationstävling för läsarna SIDA 38 förbundets satsning Schack i skolan. -

REGISTER for Transport of Animals During Short Journeys Under Article 165 of LVA Update: 06.01.2017

REGISTER for transport of animals during short journeys under article 165 of LVA Update: 06.01.2017 № and date of certificate of № and date of competence for Number the transporter address of name/identificat identification of Types of date of changes of № drivers and of transporter identification transporter ion of company ransport vehicle animals expiry data attendants animals authorisation under Art. 164 of LVA 402. 0402/16.01.2012 “Dage-Dako Montana region, ”AFIN- Iveko 65C15 with XO Live fish 1 200kg. Dachev” St. Lom city, №53 Bulgaria” Ltd, reg. №CA8056MT 0031/01.12.20 ”Slavyanska ” str. Sofia, №26A, with total area 8,40 10 Bl. Almus , entr. B, ”Raiko м² app. 3 Aleksiev” str. With contract 403. 0403/21.01.2012 Petya Dinkova Sofia city, kv. Petya Dinkova MAN 8.100 with reg. 12/06.01.2012 Large 10 Krasteva Lozenetc, №14 Krasteva №EH6495BM with ruminants ”Buntovnik” str. total area 13 м² Small 32 ruminants pigs 26 404. 0404/21.01.2012 “LIN- Iliyana Montana city, kv. “LIN- Iliyana Mitsubishi L 200 0188/19.10.20 Live fish 200 kg. Nikolova” Ltd Pliska №18, entr. Nikolova” Ltd with reg. 11 A, app. 1 №M8944AP with total area 3.04 м² 405. 0405/21.01.2012 Ahmed Piperkovo village, Ahmed Ford Tranzit with 23/14.12.2011 Large 5 Yasharov Tsenovo Yasharov reg. №P3719AX ruminants Ashimov municipality, Ruse Ashimov with total area 7 м² Small 17 region ruminants pigs 16 406. 0406/21.01.2012 “Almerta” Ltd Kardzhali city, kv. “Almerta” Ltd Fiat Ducato with reg. 44/18.01.2012 Large 6 Vazrozhdentsi, bl. -

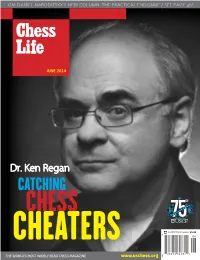

HOW to CATCH a CHESS CHEATER Ken Regan Finds Moves out of Mind

HOW TO CATCH A CHESS CHEATER Ken Regan Finds Moves Out of Mind By HOWARD GOLDOWSKY Photography LUKE COPPING "WHAT'S GOD'S RATING?" ASKS KEN REGAN, at that door." In Regan's code, the chess engine needs to play the role of an omniscient as he leads me down the stairs to the artificial intelligence that objectively evaluates and ranks, better than any human, finished basement of his house in Buffalo, every legal move in a given chess position. In other words, the engine needs to play New York. Outside, the cold intrudes on chess just about as well as God. an overcast morning in late May 2013; A ubiquitous Internet combined with button-sized wireless communications devices but in here sunlight pierces through two and chess programs that can easily wipe out the world champion make the temptation windows near the ceiling, as if this point today to use hi-tech assistance in rated chess greater than ever (see sidebar). According on earth enjoys a direct link to heaven. to Regan, since 2006 there has been a dramatic increase in the number of worldwide On a nearby shelf, old board game boxes cheating cases. Today the incident rate approaches roughly one case per month, in of Monopoly, Parcheesi, and Life pile up, which usually half involve teenagers. The current anti-cheating regulations of the with other nostalgia from the childhoods world chess federation (FIDE)are too outdated to include guidance about disciplining of Regan's two teenage children. Next to illegal computer assistance, so Regan himself monitors most major events in real- the shelf sits a table that supports a lone time, including open events, and when a tournament director becomes suspicious for laptop logged into the Department of one reason or another and wants to take action, Regan is the first man to get a call. -

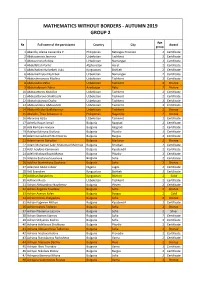

Mathematics Without Borders - Autumn 2019 Group 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - AUTUMN 2019 GROUP 2 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abanilla, Alaina Cassandra P. Philippines Batangas Province 2 Certificate 2 Abduazimova Jasmina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 3 Abduazizona Robiya Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 4 Abdulfattah Parhiz Afghanistan Herat 2 Certificate 5 Abdulhakim Nurlanbek Uulu Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 2 Certificate 6 Abdumazhidov Nodirbek Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 7 Abdurahmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 8 Abduraufov Zafar Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Bronze 9 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 2 Bronze 10 Abdusattorov Abdullox Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 11 Abdusattorova Shakhzoda Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 12 Abdushukurova Oysha Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 13 Abduvahobov Abduvahob Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 14 Abduvakhidov Bakhtiyornur Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Bronze 15 Abelado, Theo Sebastian A. Philippines Naga City 2 Bronze 16 Abrorova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 17 Achelia Hasan Ismail Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 18 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 19 Adaliya Kalinova Stoilova Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 20 Adam Genadievich Burmistrov Bulgaria Burgas 2 Certificate 21 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 2 Bronze 22 Adam Mohamed Sabri Mohamed Mahmud Bulgaria Smolyan 2 Certificate 23 Adel Ivaylova Kamenova Bulgaria Kyustendil 2 Certificate 24 Adeli Nikolova Boyadzhieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 25 Adelina Encheva Stoianova Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 26 Adelina -

Chess and Informatics

Chess and Informatics Chess and Informatics Kenneth W. Regan University at Buffalo (SUNY) CISIM 2017 Keynote Chess: “The Drosophila of AI” (Herbert Simon, John McCarthy, after Alexander Kronod) Advice for AI grad students 10 years ago: “Don’t do chess.” (I’ve lost my source but see Daniel Dennett, “Higher-order Truths About Chmess” [sic], 2006) From 1986 to 2006, I followed this advice. Turned down many requests for what I saw as “me too” computer chess. Main area = computational complexity, in which I also partner Richard Lipton’s popular blog. Then came the cheating accusations at the 2006 world championship match. Now: chess gives a window on CS advances and data-science problems. Chess and Informatics Chess and CS... Advice for AI grad students 10 years ago: “Don’t do chess.” (I’ve lost my source but see Daniel Dennett, “Higher-order Truths About Chmess” [sic], 2006) From 1986 to 2006, I followed this advice. Turned down many requests for what I saw as “me too” computer chess. Main area = computational complexity, in which I also partner Richard Lipton’s popular blog. Then came the cheating accusations at the 2006 world championship match. Now: chess gives a window on CS advances and data-science problems. Chess and Informatics Chess and CS... Chess: “The Drosophila of AI” (Herbert Simon, John McCarthy, after Alexander Kronod) (I’ve lost my source but see Daniel Dennett, “Higher-order Truths About Chmess” [sic], 2006) From 1986 to 2006, I followed this advice. Turned down many requests for what I saw as “me too” computer chess. -

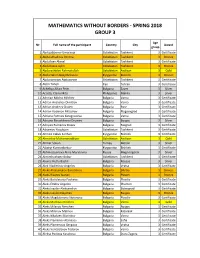

Mathematics Without Borders - Spring 2018 Group 3

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - SPRING 2018 GROUP 3 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abdujabborov Umarxoja Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Certificate 2 Abdul-Ahadova Imrona Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Bronze 3 Abdullaev Akmal Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Certificate 4 Abdullaeva Aylin Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Bronze 5 Abdurashidov Rahmatulloh Uzbekistan Andizan 3 Gold 6 Abdurrahim Bakytbekuulu Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 3 Bronze 7 Abdusamatov Abdusarvar Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Certificate 8 Abtin Taheri Iran Tehran 3 Certificate 9 Acheliya Alkan Feim Bulgaria Zavet 3 Silver 10 Acosta, Claire Mitzi Philippines Manila 3 Silver 11 Adnrian Milcho Milchev Bulgaria Varna 3 Certificate 12 Adrian Anatoliev Dimitrov Bulgaria Varna 3 Certificate 13 Adrian Andreev Dudev Bulgaria Ruse 3 Certificate 14 Adrian Vodenov Mitushev Bulgaria Blagoevgrad 3 Certificate 15 Adriana Petrova Karagyozova Bulgaria Varna 3 Certificate 16 Adriano Parashkevov Drumev Bulgaria Burgas 3 Silver 17 Adriyan Rumenov Dosev Bulgaria Razgrad 3 Certificate 18 Adxamov Yoqubjon Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Certificate 19 Ahmed Yakub Sarihan Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 3 Certificate 20 Ahmedov Muhammaddiyor Uzbekistan Andizan 3 Gold 21 Ahmet Sokun Turkey Mersin 3 Silver 22 Aibatyr Kurmanbekov Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 3 Certificate 23 Akhmetzyanova Alina Maratovna Russia Magnitogorsk 3 Silver 24 Akromhuzhaev Bobur Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Certificate 25 Aleina Mutlu Bashli Bulgaria Rousse 3 Silver 26 Alek Vladimirov Angelov Bulgaria Vratsa 3 Certificate 27 Aleks Aleksandrov Barutchiev Bulgaria Silistra 3 Bronze