The Weird and the Eerie-Repeater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

13Th Biennial Conference of the International Gothic Association

13th Biennial Conference of the International Gothic Association: Gothic Traditions and Departures Universidad de las Américas Puebla (UDLAP) 18 – 21 July 2017 Conference Draft Programme 1 Conference Schedule Tuesday 18 July 10:00 – 18:00 hrs: Registration, Auditorio Guillermo y Sofía Jenkins (Foyer). 15:00 – 15:30 hrs: Welcome remarks, Auditorio Guillermo y Sofia Jenkins. 15:30 – 16:45 hrs: Opening Plenary Address, Auditorio Guillermo y Sofía Jenkins: Isabella Van Elferen (Kingston University) Dark Sound: Reverberations between Past and Future 16:45 – 18:15 hrs: PARALLEL PANELS SESSION A A1: Scottish Gothic Carol Margaret Davison (University of Windsor): “Gothic Scotland/Scottish Gothic: Theorizing a Scottish Gothic “tradition” from Ossian and Otranto and Beyond” Alison Milbank (University of Nottingham): “Black books and Brownies: The Problem of Mediation in Scottish Gothic” David Punter (University of Bristol): “History, Terror, Tourism: Peter May and Alan Bilton” A2: Gothic Borders: Decolonizing Monsters on the Borderlands Cynthia Saldivar (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley): “Out of Darkness: (Re)Defining Domestic Horror in Americo Paredes's The Shadow” Orquidea Morales (University of Michigan): “Indigenous Monsters: Border Horror Representation of the Border” William A. Calvo-Quirós (University of Michigan): “Border Specters and Monsters of Transformation: The Uncanny history of the U.S.-Mexico Border” A3: Female Gothic Departures Deborah Russell (University of York): “Gendered Traditions: Questioning the ‘Female Gothic’” Eugene -

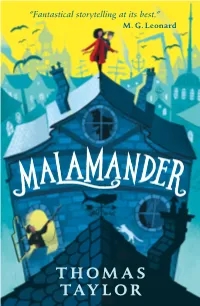

Malamander-Extract.Pdf

“Fantastical storytelling at its best.” M. G. Leonard THOMAS TAYLOR THOMAS TAYLOR This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or, if real, used fictitiously. All statements, activities, stunts, descriptions, information and material of any other kind contained herein are included for entertainment purposes only and should not be relied on for accuracy or replicated as they may result in injury. First published 2019 by Walker Books Ltd 87 Vauxhall Walk, London SE11 5HJ 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Text and interior illustrations © 2019 Thomas Taylor Cover illustrations © 2019 George Ermos The right of Thomas Taylor to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This book has been typeset in Stempel Schneider Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, taping and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-4063-8628-8 (Trade) ISBN 978-1-4063-9302-6 (Export) ISBN 978-1-4063-9303-3 (Exclusive) www.walker.co.uk Eerie-on-Sea YOU’VE PROBABLY BEEN TO EERIE-ON-SEA, without ever knowing it. When you came, it would have been summer. -

Scholarship Boys and Children's Books

Scholarship Boys and Children’s Books: Working-Class Writing for Children in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s Haru Takiuchi Thesis submitted towards the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics, Newcastle University, March 2015 ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores how, during the 1960s and 1970s in Britain, writers from the working-class helped significantly reshape British children’s literature through their representations of working-class life and culture. The three writers at the centre of this study – Aidan Chambers, Alan Garner and Robert Westall – were all examples of what Richard Hoggart, in The Uses of Literacy (1957), termed ‘scholarship boys’. By this, Hoggart meant individuals from the working-class who were educated out of their class through grammar school education. The thesis shows that their position as scholarship boys both fed their writing and enabled them to work radically and effectively within the British publishing system as it then existed. Although these writers have attracted considerable critical attention, their novels have rarely been analysed in terms of class, despite the fact that class is often central to their plots and concerns. This thesis, therefore, provides new readings of four novels featuring scholarship boys: Aidan Chambers’ Breaktime and Dance on My Grave, Robert Westall’s Fathom Five, and Alan Garner’s Red Shift. The thesis is split into two parts, and these readings make up Part 1. Part 2 focuses on scholarship boy writers’ activities in changing publishing and reviewing practices associated with the British children’s literature industry. In doing so, it shows how these scholarship boy writers successfully supported a movement to resist the cultural mechanisms which suppressed working-class culture in British children’s literature. -

After Fantastika Programme

#afterfantastika Visit: www.fantastikajournal.com After Fantastika July 6/7th, Lancaster University, UK Schedule Friday 6th 8.45 – 9.30 Registration (Management School Lecture Theatre 11/12) 9.30 – 10.50 Panels 1A & 1B 11.00 – 12.20 Panels 2A, 2B & 2C 12.30 – 1.30 Lunch 1.30 – 2.45 Keynote – Caroline Edwards 3.00 – 4.20 Panels 3A & 3B 4.30 – 6.00 Panels 4A & 4B Saturday 7th 10.30 – 12.00 Panels 5A & 5B 12.00 – 1.00 Lunch 1.00 – 2.15 Keynote – Andrew Tate 2.30 – 3.45 Panels 6A, 6B & 6C 4.00 – 5.00 Roundtable 5.00 Closing Remarks Acknowledgements Thank you to everyone who has helped contribute to either the journal or conference since they began, we massively appreciate your continued support and enthusiasm. We would especially like to thank the Department of English and Creative Writing for their backing – in particular Andrew Tate, Brian Baker, Catherine Spooner and Sara Wasson for their assistance in promoting and supporting these events. A huge thank you to all of our volunteers, chairs, and helpers without which these conferences would not be able to run as smoothly as they always have. Lastly, the biggest thanks of all must go to Chuckie Palmer-Patel who, although sadly not attending the conference in-person, has undoubtedly been an integral part of bringing together such a vibrant and engaging community – while we are all very sad that she cannot be here physically, you can catch her digital presence in panel 6B – technology willing! Thank you Kerry Dodd and Chuckie Palmer-Patel Conference Organisers #afterfantastika Visit: www.fantastikajournal.com -

Since I Began Reading the Work of Steve Ditko I Wanted to Have a Checklist So I Could Catalogue the Books I Had Read but Most Im

Since I began reading the work of Steve Ditko I wanted to have a checklist so I could catalogue the books I had read but most importantly see what other original works by the illustrator I can find and enjoy. With the help of Brian Franczak’s vast Steve Ditko compendium, Ditko-fever.com, I compiled the following check-list that could be shared, printed, built-on and probably corrected so that the fan’s, whom his work means the most, can have a simple quick reference where they can quickly build their reading list and knowledge of the artist. It has deliberately been simplified with no cover art and information to the contents of the issue. It was my intension with this check-list to be used in accompaniment with ditko-fever.com so more information on each publication can be sought when needed or if you get curious! The checklist only contains the issues where original art is first seen and printed. No reprints, no messing about. All issues in the check-list are original and contain original Steve Ditko illustrations! Although Steve Ditko did many interviews and responded in letters to many fanzines these were not included because the checklist is on the art (or illustration) of Steve Ditko not his responses to it. I hope you get some use out of this check-list! If you think I have missed anything out, made an error, or should consider adding something visit then email me at ditkocultist.com One more thing… share this, and spread the art of Steve Ditko! Regards, R.S. -

Book Reviews.5

Page 58 BOOK REVIEWS “Satan, Thou Art Outdone!” The Pan Book of Horror Stories , Herbert van Thal (ed.), with a new foreword by Johnny Mains (London: Pan Books, 2010) What does it take to truly horrify? What particular qualities do readers look for when they choose a book of horror tales over a book of ghost stories, supernatural thrillers or gothic mysteries? What distinguishes a really horrific story from a tale with the power simply to scare or disturb in a world where one person’s fears and phobias are another person’s ideas of fun? These were questions that the legendary editor Herbert van Thal and publisher Clarence Paget confronted when, in 1957, they began conspiring to put together their first ever collection of horror stories. The result of their shadowy labours, The Pan Book of Horror Stories , was an immediate success and became the premiere volume in a series of collections which were published annually and which appeared, almost without interruption, for the next thirty years. During its lifetime, The Pan Book of Horror Stories became a literary institution as each year, van Thal and Paget did their best to assemble an even more sensational selection of horrifying tales. Many of the most celebrated names in contemporary horror, including Richard Matheson, Robert Bloch and Stephen King, made early appearances between the covers of these anthologies and the cycle proved massively influential on successive waves of horror writers, filmmakers and aficionados. All the same, there are generations of horror fans who have never known the peculiar, queasy pleasure of opening up one of these collections late at night and savouring the creepy imaginings that lie within. -

Bryan Kneale Bryan Kneale Ra

BRYAN KNEALE BRYAN KNEALE RA Foreword by Brian Catling and essays by Andrew Lambirth, Jon Wood and Judith LeGrove PANGOLIN LONDON CONTENTS FOREWORD Another Brimful of Grace by Brian Catling 7 CHAPTER 1 The Opening Years by Andrew Lambirth 23 CHAPTER 2 First published in 2018 by Pangolin London Pangolin London, 90 York Way, London N1 9AG Productive Tensions by Jon Wood 55 E: [email protected] www.pangolinlondon.com ISBN 978-0-9956213-8-1 CHAPTER 3 All rights reserved. Except for the purpose of review, no part of this book may be reproduced, sorted in a Seeing Anew by Judith LeGrove 87 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Pangolin London © All rights reserved Set in Gill Sans Light BIOGRAPHY 130 Designed by Pangolin London Printed in the UK by Healeys Printers INDEX 134 (ABOVE) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 136 Bryan Kneale, c.1950s (INSIDE COVER) Bryan Kneale with Catalyst Catalyst 1964, Steel Unique Height: 215 cm 4 5 FOREWORD ANOTHER BRIMFUL OF GRACE “BOAYL NAGH VEL AGGLE CHA VEL GRAYSE” BY BRIAN CATLING Since the first draft of this enthusiasm for Bryan’s that is as telling as a storm and as monumental as work, which I had the privilege to write a couple a runic glyph. And makes yet another lens to look of years ago, a whole new wealth of paintings back on a lifetime of distinctively original work. have been made, and it is in their illumination that Notwithstanding, it would be irreverent I keep some of the core material about the life to discuss these works without acknowledging of Bryan Kneale’s extraordinary talent. -

Reflected Shadows: Folklore and the Gothic ABSTRACTS

Reflected Shadows: Folklore and the Gothic ABSTRACTS Dr Gail-Nina Anderson (Independent Scholar) [email protected] Dracula’s Cape: Visual Synecdoche and the Culture of Costume. In 1939 Robert Bloch wrote a story called ‘The Cloak’ which took to its extreme a fashion statement already well established in popular culture – vampires wear cloaks. This illustrated paper explores the development of this motif, which, far from having roots in the original vampire lore of Eastern Europe, demonstrates a complex combination of assumptions about vampires that has been created and fed by the fictional representations in literature and film.While the motif relates most immediately to perceptions of class, demonic identity and the supernatural, it also functions within the pattern of nostalgic reference that defines the vampire in modern folklore and popular culture. The cloak belongs to that Gothic hot-spot, the 1890s, but also to Bela Lugosi, to modern Goth culture and to that contemporary paradigm of ready-fit monsters, the Halloween costume shop, taking it, and its vampiric associations, from aristocratic attire to disposable disguise. Biography: Dr Gail-Nina Anderson is a freelance lecturer who runs daytime courses aimed at enquiring adult audiences and delivers a programme of public talks for Newcastle’s Literary and Philosophical Library. She is also a regular speaker at the Folklore Society ‘Legends’ weekends, and in 2013 delivered the annual Katharine Briggs Lecture at the Warburg Institute, on the topic of Fine Art and Folklore. She specialises in the myth-making elements of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and the development of Gothic motifs in popular culture. -

Title FX Volume 2

Title FX Vol. 2 Title fx vol 2 Disc Track Index Secs Description Filename Category TFX2-01 1 1 7.4 Digital Pulse Alarm Scan Warning DigitalPulseAlarmSc TFX2001 Computers & Beeps TFX2-01 2 1 4.1 Low Heavy Text Materialize Sweep LowHvyTextMateriali TFX2002 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 3 1 3.3 Heavy Text Sliding Into Shifted Rumble Short HvyTextSlidingShift TFX2003 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 4 1 4.1 Sliding Pitch Motor By SlidingPitchMotorBy TFX2004 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 5 1 6.9 Slide Multi Whoosh Phase Pitch Looped SlideMultiWhooshPha TFX2005 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 6 1 6.5 Slide Pitch Looped Sci-Fi Motorcycles SlidePitchLoopedSci TFX2006 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 7 1 6.1 Slide Pitch Looped Sci-Fi Motorcycle Slow Pitch SlidePitchLoopedSci TFX2007 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 8 1 1.4 Low Rumble Transition LowRumbleTransition TFX2008 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 9 1 2.5 Fast Text Fade Into Low Rumble Transition FstTextFadeLowRumbl TFX2009 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 10 1 2.6 Warp Tone Modulated Fade In WarpToneModulatedFa TFX2010 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 11 1 5.9 Future Mechanical Slow By FutureMechanicalSlw TFX2011 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 12 1 2.7 Heavy Mechanical Fly Transitional By Short HvyMechanicalFlyTra TFX2012 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 13 1 2.6 Mechanical Fly By Whoosh MechanicalFlyByWhoo TFX2013 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 14 1 4.1 Mechanical Fly By Modulated Slow Pitch Descending Transition MechanicalFlyByModu TFX2014 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 15 1 7.2 Mechanical Fly By Modulated -

For More Than Seventy Years the Horror Film Has

WE BELONG DEAD FEARBOOK Covers by David Brooks Inside Back Cover ‘Bride of McNaughtonstein’ starring Eric McNaughton & Oxana Timanovskaya! by Woody Welch Published by Buzzy-Krotik Productions All artwork and articles are copyright their authors. Articles and artwork always welcome on horror fi lms from the silents to the 1970’s. Editor Eric McNaughton Design and Layout Steve Kirkham - Tree Frog Communication 01245 445377 Typeset by Oxana Timanovskaya Printed by Sussex Print Services, Seaford We Belong Dead 28 Rugby Road, Brighton. BN1 6EB. East Sussex. UK [email protected] https://www.facebook.com/#!/groups/106038226186628/ We are such stuff as dreams are made of. Contributors to the Fearbook: Darrell Buxton * Darren Allison * Daniel Auty * Gary Sherratt Neil Ogley * Garry McKenzie * Tim Greaves * Dan Gale * David Whitehead Andy Giblin * David Brooks * Gary Holmes * Neil Barrow Artwork by Dave Brooks * Woody Welch * Richard Williams Photos/Illustrations Courtesy of Steve Kirkham This issue is dedicated to all the wonderful artists and writers, past and present, that make We Belong Dead the fantastic magazine it now is. As I started to trawl through those back issues to chose the articles I soon realised that even with 120 pages there wasn’t going to be enough room to include everything. I have Welcome... tried to select an ecleectic mix of articles, some in depth, some short capsules; some serious, some silly. am delighted to welcome all you fans of the classic age of horror It was a hard decision as to what to include and inevitably some wonderful to this first ever We Belong Dead Fearbook! Since its return pieces had to be left out - Neil I from the dead in March 2013, after an absence of some Ogley’s look at the career 16 years, WBD has proved very popular with fans.