The Nesting Ecology of Bumblebees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland 12 – 20 May 2018

Poland 12 – 20 May 2018 Holiday participants Gerald and Janet Turner Brian Austin and Mary Laurie-Pile Mike and Val Grogutt Mel and Ann Leggett Ann Greenizan Rina Picciotto Leaders Artur Wiatr www.biebrza-explorer.pl and Tim Strudwick. Report, lists and photos by Tim Strudwick. In Biebrza National Park we stayed at Dwor Dobarz http://dwordobarz.pl/ In Białowieża we stayed at Gawra Pensjon at www.gawra.Białowieża.com Cover photos: sunset over Lawaki fen; fallen deadwood in Białowieża strict reserve. Below: group photo taken at Dwor Dobarz and Biebrza lower basin from Burzyn. This holiday, as for every Honeyguide holiday, also puts something into conservation in our host country by way of a contribution to the wildlife that we enjoyed. The conservation contribution this year of £40 per person was supplemented by gift aid through the Honeyguide Wildlife Charitable Trust, leading to a donation of £490. The donation went to The Workshop of Living Architecture, a small NGO that runs environmental projects in and near Biebrza Marshes. This includes building new nesting platforms for white storks, often in response to storm damage or roof renovation, or simply to replace old nests. The total for all conservation contributions through Honeyguide since 1991 was £124,860 to August 2018. 2 DAILY DIARY Saturday 12 May – Warsaw to Biebrza Following an early flight from Luton, the group arrived at Warsaw airport and soon found local leader Artur and driver Rafael in the arrival hall. After introductions, including the customary carnations for the ladies, and the briefest of delays to resolve a suitcase mix up, we quickly boarded the waiting bus. -

Implications of Habitat Restoration for Bumble Bee Population Dynamics, Foraging Ecology, and Epidemiology

IMPLICATIONS OF HABITAT RESTORATION FOR BUMBLE BEE POPULATION DYNAMICS, FORAGING ECOLOGY, AND EPIDEMIOLOGY By Knute Baldwin Gundersen A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Entomology—Doctor of Philosophy Ecology, Evolutionary Biology and Behavior—Dual Major 2018 ABSTRACT IMPLICATIONS OF HABITAT RESTORATION FOR BUMBLE BEE POPULATION DYNAMICS, FORAGING ECOLOGY, AND EPIDEMIOLOGY By Knute Baldwin Gundersen Many insects provide valuable ecosystem services, including those that support our food supply. Beneficial insects such as pollinators fulfill part of this role by contributing to approximately one third of the global food crop production. Over the past few decades, pollinators have faced declining populations due to a variety of factors such as agricultural intensification, lack of floral and nesting resources, and disease. One method used in agricultural settings to help sustain pollinator populations is designating unfarmed habitat such as ditches and field margins for habitat enhancement in the form of hedgerows and wildflower strips. These floristically rich areas can be tailored to bloom both before and after crop bloom to help sustain pollinators during the time when crops are not in bloom. In turn, bee populations can benefit from the consistent availability of resources in these areas of habitat enhancement. This dissertation explores how habitat enhancement affects nesting density of a common wild pollinator, Bombus impatiens . Further, this research also aims to determine how foraging preferences change and how bumble bee disease transmission and prevalence respond to habitat enhancement. Research was conducted at 15 commercial highbush blueberry ( Vaccinium corymbosum ) fields in southwest Michigan containing either no restoration, a newly planted restoration, or a mature (5-8 year old) restoration in the field margin from 2015 to 2017. -

Review of the Diet and Micro-Habitat Values for Wildlife and the Agronomic Potential of Selected Grassland Plant Species

Report Number 697 Review of the diet and micro-habitat values for wildlifeand the agronomic potential of selected grassland plant species English Nature Research Reports working today for nature tomorrow English Nature Research Reports Number 697 Review of the diet and micro-habitat values for wildlife and the agronomic potential of selected grassland plant species S.R. Mortimer, R. Kessock-Philip, S.G. Potts, A.J. Ramsay, S.P.M. Roberts & B.A. Woodcock Centre for Agri-Environmental Research University of Reading, PO Box 237, Earley Gate, Reading RG6 6AR A. Hopkins, A. Gundrey, R. Dunn & J. Tallowin Institute for Grassland and Environmental Research North Wyke Research Station, Okehampton, Devon EX20 2SB J. Vickery & S. Gough British Trust for Ornithology The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU You may reproduce as many additional copies of this report as you like for non-commercial purposes, provided such copies stipulate that copyright remains with English Nature, Northminster House, Peterborough PE1 1UA. However, if you wish to use all or part of this report for commercial purposes, including publishing, you will need to apply for a licence by contacting the Enquiry Service at the above address. Please note this report may also contain third party copyright material. ISSN 0967-876X © Copyright English Nature 2006 Project officer Heather Robertson, Terrestrial Wildlife Team [email protected] Contractor(s) (where appropriate) S.R. Mortimer, R. Kessock-Philip, S.G. Potts, A.J. Ramsay, S.P.M. Roberts & B.A. Woodcock Centre for Agri-Environmental Research, University of Reading, PO Box 237, Earley Gate, Reading RG6 6AR A. -

Honeybee (Apis Mellifera) and Bumblebee (Bombus Terrestris) Venom: Analysis and Immunological Importance of the Proteome

Department of Physiology (WE15) Laboratory of Zoophysiology Honeybee (Apis mellifera) and bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) venom: analysis and immunological importance of the proteome Het gif van de honingbij (Apis mellifera) en de aardhommel (Bombus terrestris): analyse en immunologisch belang van het proteoom Matthias Van Vaerenbergh Ghent University, 2013 Thesis submitted to obtain the academic degree of Doctor in Science: Biochemistry and Biotechnology Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Wetenschappen, Biochemie en Biotechnologie Supervisors: Promotor: Prof. Dr. Dirk C. de Graaf Laboratory of Zoophysiology Department of Physiology Faculty of Sciences Ghent University Co-promotor: Prof. Dr. Bart Devreese Laboratory for Protein Biochemistry and Biomolecular Engineering Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology Faculty of Sciences Ghent University Reading Committee: Prof. Dr. Geert Baggerman (University of Antwerp) Dr. Simon Blank (University of Hamburg) Prof. Dr. Bart Braeckman (Ghent University) Prof. Dr. Didier Ebo (University of Antwerp) Examination Committee: Prof. Dr. Johan Grooten (Ghent University, chairman) Prof. Dr. Dirk C. de Graaf (Ghent University, promotor) Prof. Dr. Bart Devreese (Ghent University, co-promotor) Prof. Dr. Geert Baggerman (University of Antwerp) Dr. Simon Blank (University of Hamburg) Prof. Dr. Bart Braeckman (Ghent University) Prof. Dr. Didier Ebo (University of Antwerp) Dr. Maarten Aerts (Ghent University) Prof. Dr. Guy Smagghe (Ghent University) Dean: Prof. Dr. Herwig Dejonghe Rector: Prof. Dr. Anne De Paepe The author and the promotor give the permission to use this thesis for consultation and to copy parts of it for personal use. Every other use is subject to the copyright laws, more specifically the source must be extensively specified when using results from this thesis. -

Managing Alternative Pollinators a Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists

Managing Alternative Pollinators A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists ERIC MADER • MARLA SPIVAK • ELAINE EVANS Fair Use of this PDF file of Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, NRAES-186 By Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans Co-published by SARE and NRAES, February 2010 You can print copies of the PDF pages for personal use. If a complete copy is needed, we encourage you to purchase a copy as described below. Pages can be printed and copied for educational use. The book, authors, SARE, and NRAES should be acknowledged. Here is a sample acknowledgement: ----From Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, by Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans, and co- published by SARE and NRAES.---- No use of the PDF should diminish the marketability of the printed version. If you have questions about fair use of this PDF, contact NRAES. Purchasing the Book You can purchase printed copies on NRAES secure web site, www.nraes.org, or by calling (607) 255-7654. The book can also be purchased from SARE, visit www.sare.org. The list price is $23.50 plus shipping and handling. Quantity discounts are available. SARE and NRAES discount schedules differ. NRAES PO Box 4557 Ithaca, NY 14852-4557 Phone: (607) 255-7654 Fax: (607) 254-8770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nraes.org SARE 1122 Patapsco Building University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-6715 (301) 405-8020 (301) 405-7711 – Fax www.sare.org More information on SARE and NRAES is included at the end of this PDF. -

THE HUMBLE-BEE MACMILLAN and CO., Limited LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE the MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DALLAS SAN FRANCISCO the MACMILLAN CO

THE HUMBLE-BEE MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DALLAS SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO A PET QUEEN OF BOMBUS TERRESTRIS INCUBATING HER BROOD. (See page 139.) THE HUMBLE-BEE ITS LIFE-HISTORY AND HOW TO DOMESTICATE IT WITH DESCRIPTIONS OF ALL THE BRITISH SPECIES OF BOMBUS AND PSITHTRUS BY \ ; Ff W. U SLADEN FELLOW OF THE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON AUTHOR OF 'QUEEN-REARING IN ENGLAND ' ILLUSTRATED WITH PHOTOGRAPHS AND DRAWINGS BY THE AUTHOR AND FIVE COLOURED PLATES PHOTOGRAPHED DIRECT FROM NA TURE MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON 1912 COPYRIGHT Printed in ENGLAND. PREFACE The title, scheme, and some of the contents of this book are borrowed from a little treatise printed on a stencil copying apparatus in August 1892. The boyish effort brought me several naturalist friends who encouraged me to pursue further the study of these intelligent and useful insects. ..Of these friends, I feel especially indebted to the late Edward Saunders, F.R.S., author of The Hymen- optera Aculeata of the British Islands, and to the late Mrs. Brightwen, the gentle writer of Wild Nattcre Won by Kindness, and other charming studies of pet animals. The general outline of the life-history of the humble-bee is, of course, well known, but few observers have taken the trouble to investigate the details. Even Hoffer's extensive monograph, Die Htimmeln Steiermarks, published in 1882 and 1883, makes no mention of many remarkable can particulars that I have witnessed, and there be no doubt that further investigations will reveal more. -

Aberystwyth University Microsatellite Analysis Supports the Existence Of

Aberystwyth University Microsatellite analysis supports the existence of three cryptic species within the bumble bee Bombus lucorum sensu lato McKendrick, Lorraine; Provan, James; Fitzpatrick, Úna; Brown, Mark J. F.; Murray, Tómas E.; Stolle, Eckart; Paxton, Robert J. Published in: Conservation Genetics DOI: 10.1007/s10592-017-0965-3 Publication date: 2017 Citation for published version (APA): McKendrick, L., Provan, J., Fitzpatrick, Ú., Brown, M. J. F., Murray, T. E., Stolle, E., & Paxton, R. J. (2017). Microsatellite analysis supports the existence of three cryptic species within the bumble bee Bombus lucorum sensu lato. Conservation Genetics, 18(3), 573-584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-017-0965-3 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript McKendrick_MS_V3_clean.docx Click here to view linked References Microsatellite analysis supports the existence of three cryptic species within the bumble bee Bombus lucorum sensu lato Lorraine McKendrick1, Jim Provan2, Úna Fitzpatrick3, Mark J. -

Island Biology Island Biology

IIssllaanndd bbiioollooggyy Allan Sørensen Allan Timmermann, Ana Maria Martín González Camilla Hansen Camille Kruch Dorte Jensen Eva Grøndahl, Franziska Petra Popko, Grete Fogtmann Jensen, Gudny Asgeirsdottir, Hubertus Heinicke, Jan Nikkelborg, Janne Thirstrup, Karin T. Clausen, Karina Mikkelsen, Katrine Meisner, Kent Olsen, Kristina Boros, Linn Kathrin Øverland, Lucía de la Guardia, Marie S. Hoelgaard, Melissa Wetter Mikkel Sørensen, Morten Ravn Knudsen, Pedro Finamore, Petr Klimes, Rasmus Højer Jensen, Tenna Boye Tine Biedenweg AARHUS UNIVERSITY 2005/ESSAYS IN EVOLUTIONARY ECOLOGY Teachers: Bodil K. Ehlers, Tanja Ingversen, Dave Parker, MIchael Warrer Larsen, Yoko L. Dupont & Jens M. Olesen 1 C o n t e n t s Atlantic Ocean Islands Faroe Islands Kent Olsen 4 Shetland Islands Janne Thirstrup 10 Svalbard Linn Kathrin Øverland 14 Greenland Eva Grøndahl 18 Azores Tenna Boye 22 St. Helena Pedro Finamore 25 Falkland Islands Kristina Boros 29 Cape Verde Islands Allan Sørensen 32 Tristan da Cunha Rasmus Højer Jensen 36 Mediterranean Islands Corsica Camille Kruch 39 Cyprus Tine Biedenweg 42 Indian Ocean Islands Socotra Mikkel Sørensen 47 Zanzibar Karina Mikkelsen 50 Maldives Allan Timmermann 54 Krakatau Camilla Hansen 57 Bali and Lombok Grete Fogtmann Jensen 61 Pacific Islands New Guinea Lucía de la Guardia 66 2 Solomon Islands Karin T. Clausen 70 New Caledonia Franziska Petra Popko 74 Samoa Morten Ravn Knudsen 77 Tasmania Jan Nikkelborg 81 Fiji Melissa Wetter 84 New Zealand Marie S. Hoelgaard 87 Pitcairn Katrine Meisner 91 Juan Fernandéz Islands Gudny Asgeirsdottir 95 Hawaiian Islands Petr Klimes 97 Galápagos Islands Dorthe Jensen 102 Caribbean Islands Cuba Hubertus Heinicke 107 Dominica Ana Maria Martin Gonzalez 110 Essay localities 3 The Faroe Islands Kent Olsen Introduction The Faroe Islands is a treeless archipelago situated in the heart of the warm North Atlantic Current on the Wyville Thompson Ridge between 61°20’ and 62°24’ N and between 6°15’ and 7°41’ W. -

Ejt-719 Williams Altanchimeg Byvaltsev.Indd

European Journal of Taxonomy 719: 1–120 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2020.719.1107 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2020 · Williams P.H. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A4500016-C219-4353-B81C-5E0BB520547F Widespread polytypic species or complexes of local species? Revising bumblebees of the subgenus Melanobombus world-wide (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Bombus) Paul H. WILLIAMS 1,*, Dorjsuren ALTANCHIMEG 2, Alexandr BYVALTSEV 3, Roland DE JONGHE 4, Saleem JAFFAR 5, George JAPOSHVILI 6, Sih KAHONO 7, Huan LIANG 8, Maurizio MEI 9, Alireza MONFARED 10, Tshering NIDUP 11, Rifat RAINA 12, Zongxin REN 13, Chawatat THANOOSING 14, Yanhui ZHAO 15 & Michael C. ORR 16 1,14 Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK. 2 Institute of General and Experimental Biology, Peace Avenue 54b, Ulaanbaatar 13330, Mongolia. 3 Novosibirsk State University, ul. Pirogova 2, Novosibirsk, 630090 Russia. 4 Langstraat 105, B-2260 Westerlo, Belgium. 5 South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China. 6 Agricultural University of Georgia, 240 Agmashenebli Alley, Tbilisi, Georgia. 7 Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Jakarta, Indonesia. 8,13,15 Kunming Institute of Botany (Chinese Academy of Sciences), 132 Lanhei Road, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China. 9 Università di Roma ‘Sapienza’, Piazzale Valerio Massimo 6, Roma 00162, Italy. 10 Yasouj University, Zirtol, Yasouj, Iran. 11 Sherubtse College, Royal University of Bhutan, Trashigang, Bhutan. 12 Zoological Survey of India, Pali Road, Jodhpur 342005, Rajasthan, India. 16 Institute of Zoology (Chinese Academy of Sciences), 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang, Beijing 100101, China. -

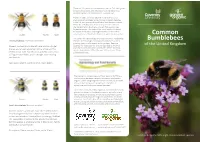

Bumblebee in the UK

There are 24 species of bumblebee in the UK. This field guide contains illustrations and descriptions of the eight most common species. All illustrations 1.5x actual size. There has been a marked decline in the diversity and abundance of wild bees across Europe in recent decades. In the UK, two species of bumblebee have become extinct within the last 80 years, and seven species are listed in the Government’s Biodiversity Action Plan as priorities for conservation. This decline has been largely attributed to habitat destruction and fragmentation, as a result of Queen Worker Male urbanisation and the intensification of agricultural practices. Common The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security is conducting Tree bumblebee (Bombus hypnorum) research to encourage and support bumblebees in food Bumblebees growing areas on allotments and in gardens. Bees are of the United Kingdom Queens, workers and males all have a brown-ginger essential for food security, and are regarded as the most thorax, and a black abdomen with a white tail. This important insect pollinators worldwide. Of the 100 crop species that provide 90% of the world’s food, over 70 are recent arrival from France is now present across most pollinated by bees. of England and Wales, and is thought to be moving northwards. Size: queen 18mm, worker 14mm, male 16mm The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security (CAFS) is a joint initiative between Coventry University and Garden Organic, which brings together social and natural scientists whose collective research expertise in the fields of agriculture and food spans several decades. The Centre conducts critical, rigorous and relevant research which contributes to the development of agricultural and food production practices which are economically sound, socially just and promote long-term protection of natural Queen Worker Male resources. -

Acoustic Communication in the Nocturnal Lepidoptera

Chapter 6 Acoustic Communication in the Nocturnal Lepidoptera Michael D. Greenfield Abstract Pair formation in moths typically involves pheromones, but some pyra- loid and noctuoid species use sound in mating communication. The signals are generally ultrasound, broadcast by males, and function in courtship. Long-range advertisement songs also occur which exhibit high convergence with commu- nication in other acoustic species such as orthopterans and anurans. Tympanal hearing with sensitivity to ultrasound in the context of bat avoidance behavior is widespread in the Lepidoptera, and phylogenetic inference indicates that such perception preceded the evolution of song. This sequence suggests that male song originated via the sensory bias mechanism, but the trajectory by which ances- tral defensive behavior in females—negative responses to bat echolocation sig- nals—may have evolved toward positive responses to male song remains unclear. Analyses of various species offer some insight to this improbable transition, and to the general process by which signals may evolve via the sensory bias mechanism. 6.1 Introduction The acoustic world of Lepidoptera remained for humans largely unknown, and this for good reason: It takes place mostly in the middle- to high-ultrasound fre- quency range, well beyond our sensitivity range. Thus, the discovery and detailed study of acoustically communicating moths came about only with the use of electronic instruments sensitive to these sound frequencies. Such equipment was invented following the 1930s, and instruments that could be readily applied in the field were only available since the 1980s. But the application of such equipment M. D. Greenfield (*) Institut de recherche sur la biologie de l’insecte (IRBI), CNRS UMR 7261, Parc de Grandmont, Université François Rabelais de Tours, 37200 Tours, France e-mail: [email protected] B. -

The Reliability of Morphological Traits in the Differentiation of Bombus

Apidologie 41 (2010) 45–53 Available online at: c INRA/DIB-AGIB/EDP Sciences, 2009 www.apidologie.org DOI: 10.1051/apido/2009048 Original article The reliability of morphological traits in the differentiation of Bombus terrestris and B. lucorum (Hymenoptera: Apidae)* Stephan Wolf, Mandy Rohde,RobinF.A.Moritz Institut für Biologie, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Hoher Weg 4, 06099 Halle/Saale, Germany Received 16 December 2008 – Revised 18 April 2009 – Accepted 30 April 2009 Abstract – The bumblebees of the subgenus Bombus sensu strictu are a notoriously difficult taxonomic group because identification keys are based on the morphology of the sexuals, yet the workers are easily confused based on morphological characters alone. Based on a large field sample of workers putatively belonging to either B. terrestris or B. lucorum, we here test the applicability and accuracy of a frequently used taxonomic identification key for continental European bumblebees and mtDNA restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) that are diagnostic for queens to distinguish between B. terrestris and B. lucorum, two highly abundant but easily confused species in Central Europe. Bumblebee workers were grouped into B. terrestris and B. lucorum either based on the taxonomic key or their mtDNA RFLP. We also genotyped all workers with six polymorphic microsatellite loci to show which grouping better matched a coherent Hardy-Weinberg population. Firstly we could show that the mtDNA RFLPs diagnostic in queens also allowed an unambiguous discrimination of the two species. Moreover, the population genetic data confirmed that the mtDNA RFLP method is superior to the taxonomic tools available. The morphological key provided 45% misclassifications for B.