REVISTA CONHECIMENTO E DIVERSIDADE 17 EDICAO Jan A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andy Woortman, 2015 Index 1. at the End of Art Everyone

ANDY WOORTMAN, 2015 INDEX 1. AT THE END OF ART EVERYONE IS AN ARTIST……page 4 2a. ATTITUDE AS METHOD – a business model……page 6 2b. NOT AN ARTIST / NOT MAKING ART……page 8 2c. CHOOSING NOT TO CHOOSE……page 9 2d. NON ARTISTS VS. PUBLIC OPINION……page 10 3. CONCLUSION……page 13 4. APPENDIX Transcript and stills from the video HOW TO BECOME A NON ARTIST by Ane Hjort Guttu, 2007……page 14 BIBLIOGRAPHY……page 27 1 “Art or the artist is per definition pretentious. It pretends to be something else than what it appears to be. So literally that means it’s pretentious.” In conversation with a friend about my thesis, Barcelona, 2014 INTRODUCTION The first time I saw Martin Creed was in a Youtube video of a lecture that he gave in the Camberwell College of Arts in 2014. He seemed to me someone who just does things randomly; not really knowing why and what for. Creed, for example, stated not having the intention or ambition of making art. While I was watching this video, I opened a second tab and found his profile on Wikipedia. I found an impressive list of past shows and won prizes, amongst which the Turner prize in 2001. As I was reading, I started to doubt my first impression. The image of a man who seemed unsure, insecure and doubtful started to turn into a well-considered concept: an artist that deliberately chooses not to choose. I stumbled upon the following in The Guardian: Creed makes me think of a really sociable philosopher. -

Inside January/February 2018 Volume 17, Number 1

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018 VOLUME 17, NUMBER 1 INSIDE Shanghai: Its Galleries and Museums Conversations with Artists in the KADIST Collection Artist Features: Pak Sheung Chen, Tsang Kin Wah, Zhu Fadong, Zhang Huan US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 1 Vol. 17 No. 1 8 VOLUME 17, NUMBER 1, JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018 CONTENTS 30 4 Editor’s Note 6 Contributors 8 Contemporary Art and the Contemporary Art Museum: Shanghai and Its Biennale John Clark 30 (Inter)Dependency: Privately Owned Art Museums in State-Sponsored West Bund 46 Xing Zhao 46 Out of Sight: Conversations with Artists in the KADIST Collection Biljana Ciric 66 Pak Sheung Chuen: Art as a Personal Journey in Times of Political Upheaval Julia Gwendolyn Schneider 80 Entangled Histories: Unraveling the Work of Tsang Kin-Wah 66 Helen Wong 85 Zhu Fadong: Why Art Is Powerless to Make Social Change Denisa Tomkova 97 Public Displays of Affliction: On Zhang Huan’s 12m2 Chan Shing Kwan 108 Chinese Name Index 80 97 Cover: In memoriam, Geng Jianyi, 1962–2017. Courtesy of Zheng Shengtian. Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art PRESIDENT Katy Hsiu-chih Chien LEGAL COUNSEL Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C. C. Liu Mainland China’s museum and gallery scene FOUNDING EDITOR Ken Lum has evolved rapidly over the past decade. Yishu EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Keith Wallace MANAGING EDITOR Zheng Shengtian 84 opens with two essays examining Shanghai, EDITORS Julie Grundvig a city that is taking strategic approaches Kate Steinmann in its recognition of culture as an essential Chunyee Li CIRCULATION MANAGER Larisa Broyde component of a vibrant urban experience. -

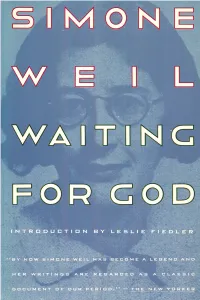

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Shock Value: the COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR?

Shock Value: THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? BY REENA JANA SHOCK VALUE: enough to prompt San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker to state, “I THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? don’t know another private collection as heavy on ‘shock art’ as Logan’s is.” When asked why his tastes veer toward the blatantly gory or overtly sexual, Logan doesn’t attempt to deny that he’s interested in shock art. But he does use predictably general terms to “defend” his collection, as if aware that such a collecting strategy may need a defense. “I have always sought out art that faces contemporary issues,” he says. “The nature of contemporary art is that it isn’t necessarily pretty.” In other words, collecting habits like Logan’s reflect the old idea of le bourgeoisie needing a little épatement. Logan likes to draw a line between his tastes and what he believes are those of the status quo. “The majority of people in general like to see pretty things when they think of what art should be. But I believe there is a better dialogue when work is unpretty,” he says. “To my mind, art doesn’t fulfill its function unless there’s ent Logan is burly, clean-cut a dialogue started.” 82 and grey-haired—the farthestK thing you could imagine from a gold-chain- Indeed, if shock art can be defined, it’s art that produces a visceral, 83 wearing sleazeball or a death-obsessed goth. In fact, the 57-year-old usually often unpleasant, reaction, a reaction that prompts people to talk, even if at sports a preppy coat and tie. -

Art, Tapu and Shared Space in Contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand

So It Vanished: Art, Tapu and Shared Space in Contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Barrett, Open Polytechnic, New Zealand In February 2012, The Dowse Art Museum (‘The Dowse’) in Lower Hutt, New Zealand cancelled an exhibition by internationally renowned Mexican artist Teresa Margolles on the ostensible grounds of culture offence. This article analyses the cancellation of Margolles’s So It Vanishes and situates it in the context of previous conflicts between Indigenous beliefs and exhibitions of transgressive art. Background information is firstly provided and Margolles’s work is sketched and compared with other taboo- breaking works of transgressive art. The Māori concept of tapu is then outlined.1 A discussion follows on the incompatibility of So It Vanishes with tapu, along with a review of other New Zealand exhibitions that have proved inconsistent with Indigenous values. Conclusions are then drawn about sharing exhibition space in contemporary Aotearoa NewZealand. Background The Dowse The Dowse is situated in Lower Hutt,2 which has traditionally been a dormitory suburb for Wellington, but today is technically a city with an increasingly cosmopolitan population. In 2006, more than one fifth of residents were born outside New Zealand 1 In this article, the words ‘taboo,’ ‘tabu’ and ‘tapu’ refer to Polynesian beliefs. Taboo, in roman font, refers to the Western adoption of the concept. The distinction lies between (literal) taboo and (figurative) taboo, the first and second definitions of ‘taboo’ provided in the Oxford English Dictionary (see Simpson & Weiner 1989: 521). 2 The Lower Hutt council has adopted the name ‘Hutt City,’ but this self-designation is not recognized by either the New Zealand Geographical Board or central government in the Local Government Act 2002. -

Proceedings of the European Society for Aesthetics Volume 6, 2014

Proceedings of the European Society for Aesthetics Volume 6, 2014 Edited by Fabian Dorsch and Dan-Eugen Ratiu Published by the European Society for Aesthetics esa Proceedings of the European Society of Aesthetics Founded in 2009 by Fabian Dorsch Internet: http://proceedings.eurosa.org Email: [email protected] ISSN: 1664 – 5278 Editors Fabian Dorsch (University of Fribourg) Dan-Eugen Ratiu (Babes-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca) Editorial Board Zsolt Bátori (Budapest University of Technology and Economics) Alessandro Bertinetto (University of Udine) Matilde Carrasco Barranco (University of Murcia) Josef Früchtl (University of Amsterdam) Robert Hopkins (University of Sheffield & New York University) Catrin Misselhorn (University of Stuttgart) Kalle Puolakka (University of Helsinki) Isabelle Rieusset-Lemarié (University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne) John Zeimbekis (University of Patras) Publisher The European Society for Aesthetics Department of Philosophy University of Fribourg Avenue de l'Europe 20 1700 Fribourg Switzerland Internet: http://www.eurosa.org Email: [email protected] Proceedings of the European Society for Aesthetics Volume 6, 2014 Edited by Fabian Dorsch and Dan-Eugen Ratiu Table of Contents Christian G. Allesch An Early Concept of ‘Psychological Aesthetics’ in the ‘Age of Aesthetics’ 1-12 Martine Berenpas The Monstrous Nature of Art — Levinas on Art, Time and Irresponsibility 13-23 Alicia Bermejo Salar Is Moderate Intentionalism Necessary? 24-36 Nuno Crespo Forgetting Architecture — Investigations into the Poetic Experience of Architecture 37-51 Alexandre Declos The Aesthetic and Cognitive Value of Surprise 52-69 Thomas Dworschak What We Do When We Ask What Music Is 70-82 Clodagh Emoe Inaesthetics — Re-configuring Aesthetics for Contemporary Art 83-113 Noel Fitzpatrick Symbolic Misery and Aesthetics — Bernard Stiegler 114-128 iii Proceedings of the European Society for Aesthetics, vol. -

Damien Hirst Visual Candy and Natural History

G A G O S I A N 7 February 2018 DAMIEN HIRST VISUAL CANDY AND NATURAL HISTORY EXTENDED! Through Saturday, March 3, 2018 7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street Central, Hong Kong I had my stomach pumped as a child because I ate pills thinking they were sweets […] I can’t understand why some people believe completely in medicine and not in art, without questioning either. —Damien Hirst Gagosian is pleased to present “Visual Candy and Natural History,” a selection of paintings and sculptures by Damien Hirst from the early- to mid-1990s. The exhibition coincides with Hirst’s most ambitious and complex project to date, “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable,” on view at Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana in Venice until December 3. Since emerging onto the international art scene in the late 1980s as the protagonist of a generation of British artists, Hirst has created installations, sculptures, paintings and drawings that examine the complex relationships between art, beauty, religion, science, life and death. Through series as diverse as the ‘Spot Paintings’, ‘Medicine Cabinets’, ‘Natural History’ and butterfly ‘Kaleidoscope Paintings,’ he has investigated and challenged contemporary belief systems, tracing the uncertainties that lie at the heart of human experience. This exhibition juxtaposes the joyful, colorful abstractions of his ‘Visual Candy’ paintings with the clinical forms of his ‘Natural History’ sculptures. Page 1 of 3 The ‘Visual Candy’ paintings allude to movements including Impressionism, Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, while the ‘Natural History’ sculptures—glass tanks containing biological specimens preserved in formaldehyde—reflect the visceral realities of scientific investigation through minimalist design. -

THBT Social Disgust Is Legitimate Grounds for Restriction of Artistic Expression

Published on idebate.org (http://idebate.org) Home > THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression The history of art is full of pieces which, at various points in time, have caused controversy, or sparked social disgust. The works most likely to provoke disgust are those that break taboos surrounding death, religion and sexual norms. Often, the debate around whether a piece is too ‘disgusting’ is interwoven with debate about whether that piece actually constitutes a work of art: people seem more willing to accept taboo-breaking pieces if they are within a clearly ‘artistic’ context (compare, for example, reactions to Michelangelo’s David with reactions to nudity elsewhere in society). As a consequence, the debate on the acceptability of shocking pieces has been tied up, at least in recent times, with the debate surrounding the acceptability of ‘conceptual art’ as art at all. Conceptual art1 is that which places an idea or concept (rather than visual effect) at the centre of the work. Marchel Duchamp is ordinarily considered to have begun the march towards acceptance of conceptual art, with his most famous piece, Fountain, a urinal signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt”. It is popularly associated with the Turner Prize and the Young British Artists. This debate has a degree of scope with regards to the extent of the restriction of artistic expression that might be being considered here. Possible restrictions include: limiting display of some pieces of art to private collections only; withdrawing public funding (e.g. -

The Theory and Practice of Visual Arts Marketing

The Tension Between Artistic and Market Orientation in Visual Art Dr Ian Fillis Department of Marketing University of Stirling Stirling Scotland FK9 4LA Email: [email protected] Introduction For centuries, artists have existed in a world which has been shaped in part by their own attitudes towards art but which also co-exists within the confines of a market structure. Many artists have thrived under the conventional notion of a market with its origins in economics and supply and demand, while others have created a market for their work through their own entrepreneurial endeavours. This chapter will explore the options open to the visual artist and examine how existing marketing theory often fails to explain how and why the artist develops an individualistic form of marketing where the self and the artwork are just as important as the audience and the customer. It builds on previous work which examines the theory and practice of visual arts marketing, noting that there has been little account taken of the philosophical clashes of art for art’s sake versus business sake (Fillis 2004a). Market orientation has received a large amount of attention in the marketing literature but product centred marketing has largely been ignored. Visual art has long been a domain where product and artist centred marketing have been practiced successfully and yet relatively little has been written about its critical importance to arts marketing theory. The merits and implications of being prepared to ignore market demand and customer wishes are considered here. 1 Slater (2007) carries out an investigation into understanding the motivations of visitors to galleries and concludes that, rather than focusing on personal and social factors alone, recognition of the role of psychological factors such as beliefs, values and motivations is also important. -

Biography • Paul Mccarthy Paul Mccarthy • Biography

BIOGRAPHY • PAUL MCCARTHY PAUL MCCARTHY • BIOGRAPHY 1945 Born in Salt Lake City, UT 1973 University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 1969 San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA 1966-1968 University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA Solo exhibitions: 2017 Kukje Gallery, ‘Cut Up and Silicone, Female Idol, WS’, Seoul, South Korea Hauser & Wirth 'WS Spinoffs, Wood Statues, Brown Rothkos’ Los Angeles, CA Fundació Gaspar, 'WS & CSSC, Drawings and Paintings', Barcelona, Spain Fondazione Giorgio Cini, ‘Paul McCarthy and Christian Lemmerz: New Media (Vir- tual Reality Art)’, Venice, Italy Deitch Projects, ‘Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley: Heidi, Midlife Crisis Trauma Center and Negative Media-Engram Abreaction Release Zone 1992’, New York, NY 2016 Hauser & Wirth, 'Paul McCarthy. Raw Spinoffs Continuations', New York, NY Xavier Hufkens, 'Paul McCarthy. White Snow & Coach Stage Stage Coach Spin- offs', Brussels, Belgium Lokremise, 'Paul McCarthy', St. Gallen, Switzerland Henry Art Gallery, 'Paul McCarthy: White Snow, Wood Sculptures', Seattle, WA 2015 Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, 'Full Exposure: Paul and Damon Mc- Carthy's Pirate Party', Durham, NC The Renaissance Society, 'Paul McCarthy. Drawings', Chicago, IL Volksbühne, 'Paul McCarthy and Damon McCarthy. Rebel Dabble Babble', Berlin, Germany Schinkel Pavillon, 'Paul McCarthy', Berlin, Germany Economou Collection, ‘Inbetween. Baselitz – McCarthy’, Athens, Greece Hauser & Wirth, ‘Paul McCarthy: Spin Offs: White Snow WS, Caribbean Pirates CP’, -

BRIGHT LIGHTS James W. Hyams Published by the Eleanor D

BRIGHT LIGHTS James W. Hyams Published by the Eleanor D. Wilson Museum at Hollins University, Roanoke, Virginia. hollins.edu/museum • 540/362-6532 Photography: Jeff Hofmann Design: Laura Jane Ramsburg This exhibition is sponsored in part by the City of Roanoke through the Roanoke Arts Commission. BRIGHT LIGHTS James W. Hyams January 18 - March 25, 2018 Eleanor D. Wilson Museum at Hollins University CONTENTS 3 Director’s Note Jenine Culligan 4 How to Become an Accidental Art Collector and Alleged Artist James W. Hyams 7 Casual Observations of an Interested Neighbor Bill Rutherfoord 28 Acknowledgements James W. Hyams Director’s Note Jenine Culligan The art-collecting bug bit Jim Hyams early and hard. Over his lifetime, he has carefully chosen an astounding collection of prints by the most important international contemporary artists. Surrounded by art in his museum-like home, Jim absorbs—and is inspired by—this work on a daily basis. Living with and loving art can be an end in itself, but sharing your collection and educating people about art is another; in this, Jim has been deeply thoughtful and generous. The Eleanor D. Wilson Museum has enjoyed a close association with Jim since the summer of 2005 when Photorealist Prints from the James W. Hyams Collection was displayed, followed in 2008 with Print as Muse: Reflections on Vanitas from the James W. Hyams Collection. Jim has been generous in donating art to the museum’s collection as well, with a print by Ron Kleeman and a mixed media work by Robert Kushner. The Eleanor D. Wilson Museum is pleased to exhibit these ten sculptures created by Jim Hyams, displayed in homage alongside the work that inspired him. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.18316/rcd.v9i17.3742 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Adams, R. (2017). 'The Saatchi Generation': Art and Advertising in the UK in the Late 20th Century. Conhecimento & Diversidade, 9(17), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.18316/rcd.v9i17.3742 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim.