Wainwrights' Mountain Had Begun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Superseding, a Prague Nocturne 141

| | | | The Return of Král Majáles PRAGUE’S INTERNATIONAL LITERARY RENAISSANCE 990-00 AN ANTHOLOGY | Edited by LOUIS ARMAND Copyright © Louis Armand, 2010 Copyright © of individual works remains with the authors Copyright © of images as captioned Published 1 May, 2010 by Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická Fakulta Litteraria Pragensia Books Centre for Critical & Cultural Theory, DALC Náměstí Jana Palacha 2 116 38 Praha 1, Czech Republic All rights reserved. This book is copyright under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright holders. Requests to publish work from this book should be directed to the publish- ers. ‘Cirkus’ © 2010 by Myla Goldberg. Used by permission of Wendy Schmalz Agency. The publication of this book has been partly supported by research grant MSM0021620824 “Foundations of the Modern World as Reflected in Literature and Philosophy” awarded to the Faculty of Philosophy, Charles University, Prague, by the Czech Ministry of Education. All reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders. | Cataloguing in Publication Data The Return of Král Majáles. Prague’s International Literary Renaissance 1990-2010 An Anthol- ogy, edited by Louis Armand.—1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 978-80-7308-302-1 (pb) 1. Literature. 2. Prague. 3. Central Europe. I. Armand, Louis. II. Title Printed in the Czech Republic by PB Tisk Cover, typeset & design © lazarus Cover image: Allen Ginsberg in Prague, 1965. Photo: ČTK. Inside pages: 1. Allen Ginsberg in Prague, 1965. Photo: ČTK. -

Jul. Tn. Nn.Lll £Bitdt Aub Shtuageh

Jul. tn. Nn.lll ®dnhrr. 1!143 £bitdt aub Shtuageh by t4t etuhtuts Year Captains Head Girls 1911 D. Stewart E. Rae 1912 B. C. Cohen M. Crowther 1913 B. C. Cohen M. Cowan 1914 J. Anderson M. Cowan 1915 I. B. Rhys E. O'Brien 1916 G. Coken V. Prowse 1917 .. J . Day M. Prynne-Jones 1918 H . Middleton D. Mllner 1919 H. Stewart E. Russell 1920 A. Ohman M. Bernard 1921 B. Bradshaw M. Bracks 1922 F . Helson L. Asquith 1923 P. Turvey L. Wilson 1924 D. Stewart M. -Backshall 1925 P. Thomas S. Kemble 1926 P. Avery M. Frisk 1927 L. Foulkes M. Clarke 1928 G. Wright E. Tollerton 1D29 A. E . Finn P . Cordon 1930 J. Tollerton M. Fealy 1931 G. Browne L. Roberts 1932 L. Stinton G. Bull 1933 .. C. Christie G. Houghton 1934 W. G. Green D. Ohman 1935 R. G. Royce M. Harris 1936 P. Ewing B. Berry 1937 R. Maguire G. Burton 1938 A. Atkins R. Wren 1939 S. Davies E . Abernethy 1940 B. England R. Alien 1941 R. Lee M. Craggs 1942 T. R. G!bson L. Hewett 1943 .. E . G. Hayman J. Bertwistle Student Officials CAPTAIN OF THE SCHOOL : E dwar d G. H aym an SENIOR GIRL PREFECT : Jill Ber twi stle SCHOOL PREFECTS: L ois Blacklock Pat vVass Georg-e 0\\'en s Barbar a Breidahl J oan vVestw ood A lan Str ahan P eggy Fin lay. on I es. Cole l ruce Wan·ell Dawn Goff !'et r H ill H enry Whi te ="'aom i Negu s Peter J ohns "SPHINX" EDITORS : Barbar a B r eidahl and B r uce ·w arre11 FACTION CAPTAINS: Blue-Barbar a B r eidahl and Des. -

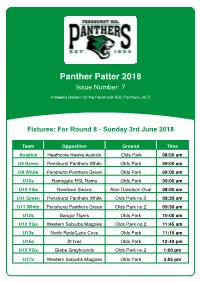

Panther Patter 2018 Issue Number: 7 a Weekly Bulletin for the Penshurst RSL Panthers JAFC

Panther Patter 2018 Issue Number: 7 A Weekly Bulletin for the Penshurst RSL Panthers JAFC Fixtures: For Round 8 - Sunday 3rd June 2018 Team Opposition Ground Time Auskick Heathcote Hawks Auskick Olds Park 08:00 am U9 Green Penshurst Panthers White Olds Park 09:00 am U9 White Penshurst Panthers Green Olds Park 09:00 am U10s Ramsgate RSL Rams Olds Park 09:00 am U10 YGs Newtown Swans Alan Davidson Oval 08:00 am U11 Green Penshurst Panthers White Olds Park no.2 09:30 am U11 White Penshurst Panthers Green Olds Park no.2 09:30 am U12s Bangor Tigers Olds Park 10:00 am U12 YGs Western Suburbs Magpies Olds Park no.2 11:45 am U13s North Ryde/Lane Cove Olds Park 11:15 am U15s St Ives Olds Park 12:40 pm U15 YGs Glebe Greyhounds Olds Park no.2 1:00 pm U17s Western Suburbs Magpies Olds Park 2:05 pm Local Indigenous Round at Waratah Oval if anyone is interested. Should be a great afternoon out. 2 Sunday 3rd June Photo Day & AFL Approved Pink Socks DAY FUNdraiser supporting National Breast Cancer Foundation — at Olds Park. Socks are available at the club for $15. Remember that these are part of our uniform on June 3rd and will be used again. PHOTO DAY TIMETABLE Auskick Round 7 Match Report Blue & Red A great day for footy today at Barden Ridge. After a fast start Aiden kicks a goal in the first minute, Aiden was supported well by Audrey, Oliver and Chase. Sam and Nils were great defenders when Bangor had the ball. -

Unforgettable Characters in Football a Series of Articles Written by H.A.De Lacy During the 1941 VFL Football Season and Published in the Sporting Globe

Unforgettable Characters in Football A series of articles written by H.A.de Lacy during the 1941 VFL football season and published in The Sporting Globe. Peter Burns Henry “Tracker” Young Albert Thurgood Henry “Ivo” Crapp Dick Lee Syd and Gordon Coventry Roy Park Jack Worrall Ivor Warne-Smith Hughie James Percy Parratt & Jimmy Freake Horrie Clover Roy Cazaly Alan and Vic Belcher Vic Cumberland Tom Fitzmaurice Rod McGregor Dave McNamara Albert Chadwick PETER BURNS Greatest Player Game Has Produced May 3, 1941 – https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/180297522 When I walked into the South Melbourne training room on Thursday night and asked a group of old timers, "Did any of YOU fellows play with Peter Burns when he was here?'' work stopped. Billy Windley left off lacing a football. "Joker" Hall allowed the compress on Eric Huxtables ankle to go cold, and Jim O'Meara walked across the room with a pencil sticking out of the side of his mouth, while one of the present-day Southern stalwarts stood half naked Waiting for the guernsey that Jim carried away in his hand. I had struck a magic chord collectively and individually all three said play with Peter — he was the greatest player the game has produced and a gentleman in all things." Well it was certainly nice to have them unanimous about It. and so definite too. I wanted Information and I got it in one hot blast of enthusiasm. Peter Burns — what a man; what a footballer, they all agreed. Today in the South Melbourne room working side by side at the moulding of a younger side. -

The Story of Jim and Phillip Krakouer. by Sean Edward Gorman BA

Moorditj Magic: The Story of Jim and Phillip Krakouer. By Sean Edward Gorman BA (Hons) Murdoch University A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At Murdoch University March 2004 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work, which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………. Sean Edward Gorman. ii ABSTRACT This thesis analyses and investigates the issue of racism in the football code of Australian Rules to understand how racism is manifested in Australian daily life. In doing this, it considers biological determinism, Indigenous social obligation and kinship structure, social justice and equity, government policy, the media, local history, everyday life, football culture, history and communities and the emergence of Indigenous players in the modern game. These social issues are explored through the genre of biography and the story of the Noongar footballers, Jim and Phillip Krakouer, who played for Claremont and North Melbourne in the late 1970’s and 1980’s. This thesis, in looking at Jim and Phillip Krakouers careers, engages with other Indigenous footballer’s contributions prior to the AFL introducing Racial and Religious Vilification Laws in 1995. This thesis offers a way of reading cultural texts and difference to understand some Indigenous and non-Indigenous relationships in an Australian context. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have often wondered where I would be if I had not made the change from work to study in 1992. In doing this I have followed a path that has taken me down many roads to many doors and in so doing I have been lucky to meet many wonderful and generous people. -

Daily Guideposts 2020 Published by Guideposts Books & Inspirational Media 110 William Street New York, New York 10038 Guideposts.Org Copyright © 2019 by Guideposts

GGPBK899_Book_MP.inddPBK899_Book_MP.indd i 111/07/191/07/19 44:15:15 PPMM Daily Guideposts 2020 Published by Guideposts Books & Inspirational Media 110 William Street New York, New York 10038 Guideposts.org Copyright © 2019 by Guideposts. All rights reserved. Th is book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Daily Guideposts is a registered trademark of Guideposts. Acknowledgments Every attempt has been made to credit the sources of copyrighted material used in this book. If any such acknowledgment has been inadvertently omitted or miscredited, receipt of such information would be appreciated. Scripture quotations marked (AMP) are taken from the Amplifi ed Bible. Copyright © 2015 by Th e Lockman Foundation, La Habra, CA 90631. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (CEB) are taken from the Common English Bible. Copyright © 2011 by Common English Bible. Scripture quotations marked (CEV) are taken from Holy Bible: Contemporary English Version. Copyright © 1995 American Bible Society. Scripture quotations marked (CSB) are taken from Th e Christian Standard Bible. Copyright © 2017 by Holman Bible Publishers. Used by permission. Scripture quotations marked (ESV) are taken from the Holy Bible, English Standard Version. Copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (GNT) are taken from the Holy Bible, Good News Translation. Copyright © 1992 by American Bible Society. Scripture quotations marked (GW) are taken from GOD’S WORD Translation. Copyright © 1995 by God’s Word to the Nations. -

Club Coach Coordinator Handbook

CLUB COACHING COORDINATOR HANDBOOK 2 AFL CLUB COACHING COORDINATOR HANDBOOK CLUB COACHING COORDINATOR HANDBOOK Acknowledgements Research, manuscript and editorial: Neil Barras Contributors: AFL Victoria – major elements of the material presented in this Handbook have been sourced from AFL Victoria and its original AFL Victoria Club Coaching Coordinator documents, Neil Barras, Anton Grbac, James McFarlane, Glenn Morley, Jason Saddington, Peter Schwab, Steve Teakel, Lawrie Woodman. Includes excerpts from the AFL Club Management Program: Planning for Football Clubs Volunteer Management for Football Clubs Junior Development for Football Clubs Project Management: Lawrie Woodman State Coaching Managers: Jack Barry (Qld), Wally Gallio (NT), Glenn Morley (WA), Brenton Phillips (SA), Nick Probert (Tas), Jason Saddington (NSW/ACT), Steve Teakel (Vic) @ 2014 Australian Football League AFL CLUB COACHING COORDINATOR HANDBOOK 3 4 AFL CLUB COACHING COORDINATOR HANDBOOK CONTENTS Introduction 6 The Role of the Club Coaching Coordinator ..............................................................................................8 The Administrative Role ...............................................................................................................................10 The Educative Role . .22 Potential Roles ...............................................................................................................................................26 Appendices ......................................................................................................................................................30 -

Coaching Curriculum Under 8-12

Appendix 9 AFL Club Coaching Curriculum COACHING CURRICULUM UNDER 8-12 Skill Extension Recommendation KICKING Drop punt In these age groups, players should be introduced to accuracy in their kicking, paying special Type of Kick both feet attention to the teaching of the drop punt for passing and goalkicking. Torpedo preferred Highlight the importance and relevance of the torpedo punt kick in the game. The coach should foot emphasise the value of this kick in gaining territory. Banana Highlight the importance and relevance of the banana (checkside) kick in the game and give time (checkside) to experiment with this kick for goal. Quick kick/snap Players should be given time to experiment with these improvised kicks for goal and to clear the ball from defence or a dangerous position. KICKING Stationary target Special attention needs to be given to the teaching of the drop punt for passing and goalkicking. Accuracy To a lead Kick to a point/area on the ground to allow player to run on to the ball. On the run Acceleration and balance are critical in teaching players to kick accurately on the run. For goal – set shot Determine distance players can kick ball for success. Balance and a straight run-up are important ingredients to an accurate kick. For goal – Determine distance players can kick ball for success. running shot For goal – Players should be given time to experiment with these improvised kicks for goal. snap shot HANDBALL Rocket Players in the age group should be introduced to the mechanics of handballing the ball from an Type of Handball open palm. -

Teachers Manual Contents

2021 TEACHERS MANUAL CONTENTS Introduction � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3 Using the Manual � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4 Recommended Teacher Timeline � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5 Freo Kwik Kick Lesson Plan � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 Freo Long Bomb Lesson Plan � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 8 Marking and Torpedo Punt Lesson Plan � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Freo Fast Ball and Bouncing Lesson Plan � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �13 Game Play Lesson Plan � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 16 NAB AFL Auskick Rules Flow Chart � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �17 Preliminary Trial Lesson Plan� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 20 Coordinator’s Checklist � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Kicking & Torpedo Punt

During this session, children will develop the skill of kicking a torpedo punt kick in a controlled environment. This is one of the basic skills of Australian Football. Teaching AGE: 9-10 KICKING & points for children, in addition to those for a drop punt kick will include holding the ball at an angle across the body toward the non-kicking foot and releasing the ball at that angle onto the boot laces. Contact is made with the ball at a point higher Middle Primary from the ground than for a drop punt. Refer to Section Nine - Skills guide. TORPEDO PUNT Session 5 FOR THIS SESSION YOU WILL NEED: 90 Mins 20 16 4 20 2 1 Setup for this age WARM-UP group is generally in 15 Mins 442041 lanework formation SEE SAW THROW: Partners lay on ground with knees bent and soles of each child’s feet touching the other’s. One child sits up and the other lies down with football above their head in outstretched hands. Child with ball sits up and with an overhead throw, passes ball to other child who catches and lies back down. Repeat WEAVE RELAY: Teams of four. One football per team. First child weaves in and out of three cones with ball underarm, then returns ball to line. Try weaving in and out backwards, sideways and bouncing ball as they weave. SKILL ACTIVITIES 35 Mins 10 12 4 20 1 LINE ACTIVITY: Coach should demonstrate and instruct players on kicking of torpedo punt: From a standing position, first child steps and kicks a Repeat second activity using opposite foot. -

Skills Guide R Chapter Chapter Chapte

SKILLS GUIDE 15 CHAPTERCHAPTER Chapter 15 Skills Guide INTRODUCTION TO SKILLS GUIDE Fundamental to coaching adolescents in any sport is the need to know about the skills of the game. The following guide provides coaches with the key points for each of the skills of Australian Football. Although it is recognised that the ability of the coach to teach the fundamental skills (techniques) of Australian Football is paramount, equally important at the youth age group is the ability to analyse, correct and remediate common skill errors players have developed over their playing experiences. Only then will the coach of this age group truly improve the playing ability and enjoyment of the players and develop them into confident and competent senior players. When referring to the various skills, coaches should: • Identify the skill or combination of skills to be taught. • Note the sequence of teaching points. • Select only two or three points to start with (refer to Chapter 5, Teaching and Improving Skills) Use the SPIR method to teach the skill. An essential starting point for this is to provide players with a good visual demonstration of the skill being taught. This may require selecting a player to perform the demonstration. Also, when teaching the skills, be aware of how to increase intensity or difficulty. Start with static activity (player handballs to partner – both stationary). The skill is made more difficult by increasing the pace and reducing the time and space in which the skill is to be performed (it becomes more game based). When teaching skills, remember to: • Start with slow movement (players step towards each other). -

An Investigation of Jandek's

THEMATIC INTERCONNECTIVITY AS AN INNATE MUSICAL QUALITY: AN INVESTIGATION OF JANDEK’S “EUROPEAN JEWEL” GUITAR RIFFS NICOLE A MARCHESSEAU A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY 2014 © NICOLE A MARCHESSEAU, 2014 Abstract This dissertation is divided into two main areas. The first of these explores Jandek-related discourse and contextualizes the project. Also discussed is the interconnectivity that runs through the project through the self-citation of various lyrical, visual, and musical themes. The second main component of this dissertation explores one of these musical themes in detail: the guitar riffs heard in the “European Jewel” song-set and the transmigration/migration of the riff material used in the song to other non-“European Jewel” tracks. Jandek is often described in related discourse as an “outsider musician.” A significant point of discussion in the first area of this dissertation is the outsider music genre as it relates to Jandek. In part, this dissertation responds to an article by Martin James and Mitzi Waltz which was printed in the periodical Popular Music where it was suggested that the marketing of a musician as an outsider risks diminishing the “innate qualities” of the so-called outsider musicians’ works.1 While the outsider label is in itself problematic—this is discussed at length in Chapter Two—the analysis which comprises the second half of this dissertation delves into self- citation and thematic interconnection as innate qualities within the project.