Guideposts to Recognition: Cognition, Memory & Brain Injury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Neuroinflammation and Functional Connectivity in Alzheimer's Disease: Interactive Influences on Cognitive Performance

Research Articles: Neurobiology of Disease Neuroinflammation and functional connectivity in Alzheimer's disease: interactive influences on cognitive performance https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2574-18.2019 Cite as: J. Neurosci 2019; 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2574-18.2019 Received: 5 October 2018 Revised: 25 March 2019 Accepted: 11 April 2019 This Early Release article has been peer-reviewed and accepted, but has not been through the composition and copyediting processes. The final version may differ slightly in style or formatting and will contain links to any extended data. Alerts: Sign up at www.jneurosci.org/alerts to receive customized email alerts when the fully formatted version of this article is published. Copyright © 2019 Passamonti et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided that the original work is properly attributed. 1 Neuroinflammation and functional connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease: 2 interactive influences on cognitive performance 3 4 L. Passamonti1*, K.A. Tsvetanov1*, P.S. Jones1, W.R. Bevan-Jones2, R. Arnold2, R.J. Borchert1, 5 E. Mak2, L. Su2, J.T. O’Brien2#, J.B. Rowe1,3# 6 7 Joint *first and #last authorship 8 9 10 Authors’ addresses 11 1Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 12 2Department of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 13 3Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Medical Research Council, Cambridge, -

![Neurocognitive and Functional Impairment in Adult and Paediatric Tuberculous Meningitis [Version 1; Peer Review: 2 Approved]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2973/neurocognitive-and-functional-impairment-in-adult-and-paediatric-tuberculous-meningitis-version-1-peer-review-2-approved-412973.webp)

Neurocognitive and Functional Impairment in Adult and Paediatric Tuberculous Meningitis [Version 1; Peer Review: 2 Approved]

Wellcome Open Research 2019, 4:178 Last updated: 20 MAY 2021 REVIEW Neurocognitive and functional impairment in adult and paediatric tuberculous meningitis [version 1; peer review: 2 approved] Angharad G. Davis 1-3, Sam Nightingale4, Priscilla E. Springer 5, Regan Solomons 5, Ana Arenivas6,7, Robert J. Wilkinson 2,8,9, Suzanne T. Anderson10,11*, Felicia C. Chow 12*, Tuberculous Meningitis International Research Consortium 1University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK 2Francis Crick Institute, Midland Road, London, NW1 1AT, UK 3Institute of Infectious Diseases and Molecular Medicine. Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Observatory, 7925, South Africa 4HIV Mental Health Research Unit, University of Cape Town,, Observatory, 7925, South Africa 5Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa 6The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research Memorial Hermann, Department of Rehabilitation Psychology and Neuropsychology,, Houston, Texas, USA 7Baylor College of Medicine, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Houston, Texas, USA 8Department of Infectious Diseases, Imperial College London, London, W2 1PG, UK 9Wellcome Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Africa, Institute of Infectious Diseases and Molecular Medicine at Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Observatory, 7925, South Africa 10MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL, University College London, London, WC1E 6BT, UK 11Evelina Community, Guys and St Thomas’ -

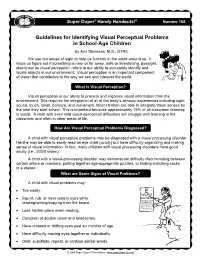

Visual Perceptual Skills

Super Duper® Handy Handouts!® Number 168 Guidelines for Identifying Visual Perceptual Problems in School-Age Children by Ann Stensaas, M.S., OTR/L We use our sense of sight to help us function in the world around us. It helps us figure out if something is near or far away, safe or threatening. Eyesight, also know as visual perception, refers to our ability to accurately identify and locate objects in our environment. Visual perception is an important component of vision that contributes to the way we see and interpret the world. What Is Visual Perception? Visual perception is our ability to process and organize visual information from the environment. This requires the integration of all of the body’s sensory experiences including sight, sound, touch, smell, balance, and movement. Most children are able to integrate these senses by the time they start school. This is important because approximately 75% of all classroom learning is visual. A child with even mild visual-perceptual difficulties will struggle with learning in the classroom and often in other areas of life. How Are Visual Perceptual Problems Diagnosed? A child with visual perceptual problems may be diagnosed with a visual processing disorder. He/she may be able to easily read an eye chart (acuity) but have difficulty organizing and making sense of visual information. In fact, many children with visual processing disorders have good acuity (i.e., 20/20 vision). A child with a visual-processing disorder may demonstrate difficulty discriminating between certain letters or numbers, putting together age-appropriate puzzles, or finding matching socks in a drawer. -

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory What is Metacognition? The simplest definition of metacognition is “thinking about thinking.” This refers to the “self-regulation” effective learners exhibit, meaning they are aware of their learning process and can measure how efficiently they are learning as they study. Essentially, metacognition involves two simultaneous levels of thought: the first level is the student’s thinking/learning about the specific subject content and the second level is the student’s thinking about his/her learning. A student practicing metacognition would ask him/herself “How am I thinking?” or “Where am I in the learning process? Am I learning/understanding this topic? How could I learn more effectively?” These two levels are: knowledge and regulation. Students who are metacognitively aware demonstrate self-knowledge: They know what strategies and conditions work best for them while they are learning. Declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge are essential for developing conceptual knowledge (content knowledge). Regulation refers to students’ knowledge about the implementation of strategies and the ability to monitor the effectiveness of their strategies. When students regulate, they are continually developing and monitoring their learning strategies based on their evolving self-knowledge. Complete the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory to assess your metacognitive processes. The Inventory Check True or False for each statement below. After you complete the inventory, use the scoring guide. Contact an Academic Coach at the Academic Support Center at (856) 681-6250 to discuss your results and strategies to increase your metacognitive awareness. True False 1. I ask myself periodically if I am meeting my goals. 2. I consider several alternatives to a problem before I answer. -

Cognition, Affect, and Learning —The Role of Emotions in Learning

How People Learn: Cognition, Affect, and Learning —The Role of Emotions in Learning Barry Kort Ph.D. and Robert Reilly Ed.D. {kort, reilly}@media.mit.edu formerly MIT Media Lab Draft as of date January 2, 2019 Learning is the quintessential emotional experience. Our species, Homo Sapiens, are the beings who think. We are also the beings who learn, and the beings who simultaneously experience a rich spectrum of affective emotional states, including a selected suite of emotional states specifically and directly related to learning. This proposal reviews previously published research and theoretical models relating emotions to learning and cognition and presents ideas and proposals for extending that research and reducing it to practice. Our perspective The concept of affect in learning (i.e., emotions in learning) is the same pedagogy applied by an athletic coach at a sporting event. A coach recognizes the affective state of an athlete, and, for example, exhorts that athlete toward increased performance (e.g., raises the level of enthusiasm), or, redirects a frustrated athlete to a productive affective state (e.g., instills confidence, or pride). A coach recognizes that an athlete’s affective state is a critical factor during performance; and, when appropriate, a coach will intervene with a meaningful strategy or tactic. Athletic coaches are skilled at recognizing affective states and intervening appropriately. Educators can have the same impact on a learner by understanding a learner’s affective state and intervening with appropriate strategies or tactics that will meaningfully manage and guide a person’s learning journey. There are several learning theories and a great deal of neuroscience/affective research. -

Cognitive Impairment/Dementia – Summary

Cognitive Impairment/Dementia Care Guide December 2014 SUMMARY GOALS Early identification of affected patients Prevention of victimization Reduce symptom severity Improve quality of life ALERTS Victimized patients Increase in rules violation behaviors Worsening personal hygiene Anxiety and agitation, especially at night Complete Advance Directive-Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care (DPAHC) early in course of disease Prison environment may mask symptoms DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA/EVALUATION Definition - Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) Cognitive decline greater than expected for age and education level without significantly interfering with activities of daily life. Evidence of memory impairment Preservation of general cognitive and functional abilities Absence of diagnosed dementia Definition - Dementia Cognitive impairment with: significant decline from previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains (complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, social cognition, perceptual motor) interference with independence in daily activities Not occurring exclusively with delirium Not better explained by another disorder Neurobehavioral abnormalities History - MCI and Dementia patients may have similar historical findings which contribute to the ultimate diagnosis: Poor adherence to rules and routines Personal hygiene problems Impaired comprehension History of head injury, substance abuse, or other medical contributors Differential Diagnosis – Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) Medication -

Chapter 14: Individual Differences in Cognition 369 Copyright ©2018 by SAGE Publications, Inc

INDIVIDUAL 14 DIFFERENCES IN COGNITION CHAPTER OUTLINE Setting the Stage Individual Differences in Cognition Ability Differences distribute Cognitive Styles Learning Styles Expert/Novice Differences or The Effects of Aging on Cognition Gender Differences in Cognition Gender Differences in Skills and Abilities Verbal Abilities Visuospatial Abilities post, Quantitative and Reasoning Abilities Gender Differences in Learning and Cognitive Styles Motivation for Cognitive Tasks Connected Learning copy, not SETTING THE STAGE .................................................................. y son and daughter share many characteristics, but when it comes Do to school they really show different aptitudes. My son adores - Mliterature, history, and social sciences. He ceremoniously handed over his calculator to me after taking his one and only college math course, noting, “I won’t ever be needing this again.” He has a fantastic memory for all things theatrical, and he amazes his fellow cast members and directors with how quickly he can learn lines and be “off book.” In contrast, my daughter is really adept at noticing patterns and problem solving, and she Proof is enjoying an honors science course this year while hoping that at least one day in the lab they will get to “blow something up.” She’s a talented dancer and picks up new choreography seemingly without much effort. These differences really don’t seem to be about ability; Tim can do statis- tics competently, if forced, and did dance a little in some performances, Draft and Kimmie can read and analyze novels or learn about historical topics and has acted competently in some school plays. What I’m talking about here is more differences in their interests, their preferred way of learning, maybe even their style of learning. -

Cognitive Retention of Generation Y Students Through the Use of Games

11 COGNITNE RETENTION OF GENERATION Y STUDENTS THROUGH THE USE OF GAMES AND SIMULATIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Argosy University - Sarasota In partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Business Administration Accounting Major by Melanie A. Hicks Argosy University - Sarasota August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. III Abstract A new generation of students has begun to proliferate colleges and universities. Unlike previous generations, Generation Y students have been exposed to a variety of technological advancements, have different behaviors towards learning, and have been raised in a different environment. These differences may be causing conflict with traditional pedagogy in educational institutions, thereby creating, while it may be unintentional, an inability for Generation Y students to learn under the standard educational method of lecture presented to previous generations. The literature supports the position that additional teaching methods are needed in order to effectively educate Generation Y students (Prensky, 2001; Brozik & Zapalska, 1999; Albrecht, 1995). Consequently, the primary goal of this dissertation is to examine the ability of Generation Y students to achieve greater cognitive retention when the instructional material is conveyed with the assistance of or through the use of games andlor simulations. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. IV © Copyright 2007 by Melanie A. Hicks Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Scott Hicks, who has encouraged me and constantly pushed me to "seek first to understand, then to be understood". -

The Cognitive Basis of Dyslexia in School-Aged Children: a Multiple Case

The cognitive basis of dyslexia The cognitive basis of dyslexia in school-aged children: a multiple case study in a transparent orthography Agnieszka Dębska1*, Magdalena Łuniewska1,2*, Julian Zubek2, Katarzyna Chyl1, Agnieszka Dynak1,2, Gabriela Dzięgiel-Fivet1, Joanna Plewko1, Katarzyna Jednoróg1, Anna Grabowska3 * these authors contributed equally to the paper 1Laboratory of Language Neurobiology, Nencki Institute of Experimental Biology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland 2 Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland 3Faculty of Psychology, SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Warsaw, Poland Laboratory of Language Neurobiology Nencki Institute of Experimental Biology, Polish Academy of Sciences ul. Pasteura 3, 02-093 Warszawa, Poland Conflict of Interest Statement None of the authors has to declare a conflict of interest. Supplementary materials 1. Tables and Figures 2. Supplementary materials S1, S2, S3 and S4 1 The cognitive basis of dyslexia The cognitive basis of dyslexia in school-aged children: a multiple case study in a transparent orthography Research highlights ● This study tested the (co)existence of cognitive deficits in dyslexia in phonological awareness, rapid naming, visual and selective attention, auditory skills, and implicit learning. ● The most frequent deficits in Polish children with dyslexia included a phonological (51%) and a rapid naming deficit (26%), which coexisted in 14% of children. ● Despite the severe reading impairment, 26% of children with dyslexia presented no deficits in measured cognitive abilities. ● RAN explains reading skills variability across the whole spectrum of reading ability; phonological skills explain variability best among average and good readers but not poor readers. Abstract This study focused on the role of numerous cognitive skills such as phonological awareness (PA), rapid automatized naming (RAN), visual and selective attention, auditory skills, and implicit learning in developmental dyslexia. -

Will It Blend? Information Systems and Computer Engineering

Will It Blend? Studying Color Mixing Perception Paulo Duarte Esperanc¸a Garcia Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Prof. Dra. Sandra Pereira Gama Examination Committee Chairperson: Prof. Dr. Antonio´ Manuel Ferreira Rito da Silva Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Member of the Committee: Prof. Dr. Manuel Joao˜ Caneira Monteiro da Fonseca November 2016 Acknowledgments First, I want to thank my advisor Professor Daniel Gonc¸alves for his excellent guidance, for always having the availability to teach, help and clarify, for his enormous knowledge and expertise, and for al- ways believing in the best result possible of this Master Thesis. Then, I also want to thank my co-advisor Sandra Gama, for her more-than-valuable inputs on Information Visualization and for opening the path for this dissertation and others to come! Additionally, I would like to thank everyone which somehow contributed for this thesis to happen: everyone who participated either online, or on the laboratory sessions, specially those who did it so willingly, without looking at the rewards. Without them, there would be no validity is this thesis. I must express my very profound gratitude to my family, particularly my mother Ondina and brother Diogo, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you! Finally, to my girlfriend Margarida, my beloved partner, my shelter and support, for all the sleepless nights, sweat and tears throughout the last seven years. -

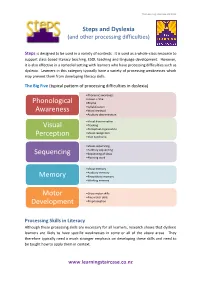

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word.