Tsukuba Science City: Between the Creation of Innovative Milieu and the Erasure of Furusato Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

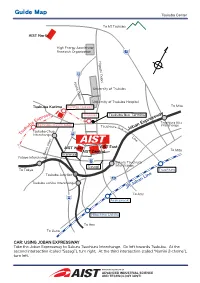

Guide Map Tsukuba AIST

Guide Map Tsukuba Center To Mt.Tsukuba AIST North High Energy Accelerator Research Organization 125 Higashi Odori 408 Nishii Odori University of Tsukuba University of Tsukuba Hospital Tsukuba Karima Kenkyu Gakuen To Mito Tsukuba Bus Terminal ess Tsukuba pr Ex a Tsuchiura Kita b Interchange u Bampaku Kinen Koen Tsuchiura k Ga u ku Joban Expressway s Tsukuba-Chuo en 408 T Interchange L in e AIST West AIST East To Mito AIST Central Sience Odori Inarimae Yatabe Interchange 354 Sakura Tsuchiura Sasagi Interchange To Tokyo Tsuchiura Tsukuba Junction 6 Tsukuba ushiku Interchange JR Joban Line To Ami 408 Arakawaoki Hitachino Ushiku To Ami To Ueno CAR: USING JOBAN EXPRESSWAY Take the Joban Expressway to Sakura Tsuchiura Interchange. Go left towards Tsukuba. At the second intersection (called “Sasagi”), turn right. At the third intersection (called “Namiki 2-chome”), turn left. Guide Map Tsukuba Center TRAIN: USING TSUKUBA EXRESS Take the express train from Akihabara (45 min) and get off at Tsukuba Station. Take exit A3. (1) Take the Kanto Tetsudo bus going to “Arakawaoki (West Entrance) via Namiki”, “South Loop-line via Tsukuba Uchu Center” or “Sakura New Town” from platform #4 at Tsukuba Bus Terminal. Get off at Namiki 2-chome. Walk for approximately 3 minutes to AIST Tsukuba Central. (2) Take a free AIST shuttle bus. Several NIMS shuttle buses go to AIST Tsukuba Central via NIMS and AIST Tsukuba East and you may take the buses at the same bus stop. Please note that the shuttle buses are small vehicles and they may not be able to carry all visitors. -

Kashiwa-No-Ha Smart City

Kashiwa-no-ha Smart City Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd. 1. Location Location 25 km from central Tokyo 27 minutes by Tsukuba Express from Akihabara Tokyo Access Airport Access Tokyo: 30 min Haneda: 58 min Akihabara: 27 min by Train Narita: 62 min by Train Roppongi: 50 min Haneda (54km): 60 min by Car Narita (48km): 60 min Note: Excluding transfer and waiting times Area under Development Kashiwa-no-ha Campus To Tsukuba Kashiwa Interchange of Joban Expressway Kashiwa-no-ha Park A land readjustment project area Tsukuba Express covering roughly 273 hectares and with a planned population of 26,000 Developed from scratch Leveraging advanced knowledge Kashiwa-no-ha Campus Station and technologies A social experiment in which residents are participating To Akihabara The Transitional Process of Community Building 2000 2001 2003 2005 2006 Opening of Center for Opening of Urban Opening of Opening of Closing of the Environment Health Opening of the Design Center LaLaport University of Tokyo Mitsui Kashiwa and Field Sciences, Tsukuba Kashiwa-no-ha Kashiwanoha Kashiwa Campus Golf Club Chiba University Express Line (UDCK) (Approx. 160 shops) Commencement of the Land Readjustment Project 2008 2009 2011 2012 2014 Kashiwa-no-ha Recognized as Completion of Park City Opening of Gate Square, International Completion of Park City “Comprehensive Kashiwanoha Campus The Core of the Ekimae Campus Town Kashiwanoha Campus Special Zone” and Second Avenue (Station-front) Initiative First Avenue “Environmental (880 Housing Units) Town Center (977 Housing Units) Future City” 1st Stage - The Completion of the Initial Period 2nd Stage Kashiwa-no-ha Campus Station Area in 2014 Kashiwa Interchange of Joban Expressway University of Tokyo Toyofuta Industrial Park Kashiwanoha Park Konbukuro Pond Park Government research center Kashiwa-no-ha High School Chiba STAGE Ⅱ University Nibangai (880 units) Tsukuba Express Line LaLaport KASHIWANOHA Gate Square STAGE Ⅰ Route No. -

University of Tsukuba at a Glance

Maps and Data University of Tsukuba At a Glance 2019 Academic Year (Apr. 1 - Mar. 31) 1 HISTORY & CREST & SLOGAN ■ History Since its inception in Tsukuba Science City in 1973, the University of Tsukuba has offered a comprehensive curriculum of education, covering everything from literature and science to fine arts and physical education. Although the university’s roots stretch back much further than 40 years; its origins lie in the Normal School, the first of its kind in Japan, established in 1872 on the former site of Shoheizaka Gakumonjo. The school was renamed several times over the years, eventually becoming Tokyo Higher Normal School before incorporating four institutions—Tokyo Higher Normal School, Tokyo University of Literature and Science, Tokyo College of Physical Education, and Tokyo College of Agricultural Education—in 1949 to become the Tokyo University of Education, the forerunner to today’s University of Tsukuba. ■ Crest The University of Tsukuba’s “five-and-three paulownia” crest derives from the emblem adopted by Tokyo Higher Normal School students in 1903 for their school badge, which was inherited by the Tokyo University of Education in 1949. Later, in 1974, the University Council officially approved the crest as the school insignia of the University of Tsukuba. The “five-and-three paulownia” design is based on a traditional Japanese motif, but brings a unique variation to the classic style: the University of Tsukuba crest is different because only the outline of the leaves is depicted. The color of the crest is CLASSIC PURPLE, the official color of the University of Tsukuba. ■ Slogan (Japanese) 開かれた未来へ。 Since its inception, the University of Tsukuba’s philosophy has been one of openness as we seek to forge a better future through education, research, and all other aspects of academia. -

TANI BUNCHÔ (1763-1840) Subject: Mount Tsukuba Signed

TANI BUNCHÔ (1763-1840) Subject: Mount Tsukuba Signed: Bunchô Sealed: Bunchô ga in Date: 1804-18 (Bunka era) Dimensions: 77 1/8 x 145 5/8 (exclusive of mount) Format: Six-fold screen [other screen depicting Mount Fuji is in the collection of the museum at Utsunomiya Geijutsu Daigaku] Media: Ink and color on gold leaf Price: POR This majestic and exceptionally tall screen by Tani Bunchô is a powerful image illustrating this artist’s creative leadership in an artistic movement called the Yamato-e Revivalist School (Fukko Yamato-e ha). Aimed at reviving the styles and themes of the traditional Yamato-e painting, focusing on the past models of the Tosa school, this aesthetic was also combined with the complexity of the literati (bunjinga) traditions. This screen was originally created as a pair of six-fold screens with the mate depicting the most celebrated site in Japan, Mount Fuji; that screen is in the collection of the Utsunomiya Geijutsu Daigaku (Utsunomiya Art University). This screen of Mount Tsukuba with its expressive brushwork, strong use of ink and green pigment, and masterful use of negative space creates a scene that has a mystical appearancewith deep recession in space. The signature on the screen dates it to the Bunka era (180418), when Bunchô was at the height of his popularity. Furthermore, it was mentioned in thediary of Matsudaira Sadanobu (1758-1829) the celebrated daimyô, financial reformer, chief senior councilor of the Tokugawa Shogunate, that Buncho painted a pair of screens of Mounts Tsukuba and Fuji before his very eyes. To date, these are the only known pair of screens by Bunchô of this subject and might be those so described. -

Rugby World Cup™ Japan 2019 Host City, Kumagaya and Saitama

Rugby World Cup™ Japan 2019 Host City, Kumagaya and Saitama Prefecture Fact Book 2019.9 Ver.1 1 Index • Rugby World Cup™ - Kumagaya・Saitama • Host City, Kumagaya • SKUMAM ! KUMAGAYA • Kumagaya Rugby Stadium • Fan Zone • What to Eat in Kumagaya • What to Drink in Kumagaya • What to See in Kumagaya and Gyoda • The Main Attractions of Saitama • Saitama Media tour, Monday, Oct 7th • Contact Details for the Media and Photos 2 Rugby World Cup™ 2019 - Kumagaya・Saitama ■There is One Pre-Match in the Kumagaya Rugby Stadium Friday, Sep 6th, 19:15: Japan VS. South Africa ■There are three Official Rugby World Cup Matches in the Kumagaya Rugby Stadium ■Team Camps in Saitama Prefecture There are 52 team camps across Japan. In Saitama Prefecture, Kumagaya city and Saitama City will host 7 nations. Host City, Kumagaya ■ Kumagaya City, Saitama Prefecture, is conveniently located only 50–70 kilometers north of Tokyo. ■ Rugby Town Kumagaya: Kumagaya’s rugby history dates back to 1959, when the Kumagaya Commerce and Industrial High School’s rugby club entered the national tournament for the first time. ■ In 1967, a national sports festival was to be held in Saitama Prefecture, and Kumagaya City took this opportunity to hold a range of rugby activities along the Arakawa River. ■ In 1991, Kumagaya Rugby Stadium, one of the leading rugby-dedicated stadiums in Japan, was completed. ■ Tag Rugby has been introduced to every elementary school and as of August 2018, there are 14 rugby clubs in Kumagaya, consisting of men, women, boys, and girls of all ages. For details, please see pages five and six of the brochure “RUGBY WORLD CUP™ JAPAN2019 SAITAMA・KUMAGAYA ■Access from Tokyo Station 40 minutes to Kumagaya Station, via the JR Joetsu or Hokuriku Shinkansen: ¥3,190, 1 hour and 15 minutes to Kumagaya Station, via the JR Takasaki line: ¥1,140. -

Mitsui Garden Hotel Kashiwa-No-Ha

A breeze of pre-eminent hospitality welcomes you Our hotel has been built Lobby Entrance around the concepts of practicality and comfort. Please relax and enjoy the surroundings of “Kashiwa-no-ha Gate Square”. Check In 15:00 / Check Out 11:00 148-2 Kashiwanoha Campus, 178-4 Wakashiba, Kashiwa-city, Chiba, 277-0871 TEL:04-7134-3131 FAX: 04-7135-3181 Moderate Queen Guest room information Deluxe Studio Queen スタジオダブルD Moderate Twin【 22.6㎡】 Serviced Apartment (7F)【24.7-62.8㎡】 The green and wood décor make for a relaxed ambiance in our stylish twin rooms. These apartment-style rooms feature a kitchen area, furniture and home appliances, Whilst naturally perfect for couples, some of them also feature a sofa bed, allowing making them ideal for medium to long-term stay guests. them to accommodate up to 3 guests. Various types are available ranging from single to family size. Executive Twin【 45.3㎡】 Moderate Double【 19.8㎡】 These spacious rooms feature a A 19.8m² room that places emphasis on separate bathroom, toilet and make-up comfort and functionality. A semi-double area to maximize your comfort during bed ensures a relaxing night's sleep. your stay. Fourth (living) Executive Studio Queen Deluxe Studio Queen Moderate Queen【 21.4㎡】 Accessible Double【 22.6㎡】 (bathroom) (kitchen) Our standard room, featuring a wall This functional room allows all guests ●Unit kitchen ●Electric kettle ●DVD player mounted TV to make maximize space. (including the elderly and those with Serviced ●Cooking utensils ●LCD television ●Mobile phone charger Perfect for business and leisure guests alike. -

Dukeite from the Kinkei Mine, Chino City, Nagano Prefecture, Japan

Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Ser. C, 38, pp. 1–5, December 22, 2012 Dukeite from the Kinkei mine, Chino City, Nagano Prefecture, Japan Akira Harada1, Takashi Yamada1, Satoshi Matsubara2, Ritsuro Miyawaki2, Masako Shigeoka2, Hiroshi Miyajima3 and Hiroshi Sakurai4 1 Friends of Minerals, Tokyo, 4–13–18 Toyotamanaka, Nerima, Tokyo 176–0013, Japan 2 Department of Geology and Paleontology, National Museum of Nature and Science, 4–1–1 Amakubo, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–0005, Japan 3 Fossa Magna Museum, Miyama Park, Itoigawa, Niigata 941–0056, Japan 4 Mineralogical Society of Nagoya, 2–2–4–106 Daikominami, Higashi, Nagoya 461–0047, Japan Abstract Dukeite is found in small cavities of quartz–chromian muscovite vein from the Kinkei mine, Chino City, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. It occurs as bright yellow hemispherical aggregates up to 2 mm in diameter composed of minute lath-like crystals in association with very minute rhombic crystals of waylandite. The specimens were collected from an outcrop of gold ore deposit. An electron microprobe analysis for the most Te-rich dukeite gave Bi2O3 85.77, CrO3 11.83, TeO3 0.81, 6+ 6+ H2O (calc.) 1.66, total 100.07 wt.%. The empirical formula is: Bi23.98(Cr 7.71Te 0.30)Σ8.01O57(OH)6·3H2O on the basis of O=66 excluding H2O. The strongest eight lines of the X-ray powder diffraction pattern obtained by using a Gandolfi camera [d in Å (I) (hkl)] are: 7.67 (10) (002), 3.84 (12) (004), 3.77 (14) (220), 3.38 (100) (222), 2.69 (31) (224), 2.56 (8) (006), 2.18 (16) (600), 2.12 (9) (226). -

Effects of Solar Radiation Amount and Synoptic-Scale Wind on the Local Wind “Karakkaze” Over the Kanto Plain in Japan

Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan, Vol. 89, No. 4, pp. 327–340, 2011 327 DOI:10.2151/jmsj.2011-403 Effects of Solar Radiation Amount and Synoptic-scale Wind on the Local Wind “Karakkaze” over the Kanto Plain in Japan Hiroyuki KUSAKA Center for Computational Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan Yukako MIYA and Ryosaku IKEDA Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan (Manuscript received 21 August 2009, in final form 30 May 2011) Abstract A climatological and numerical study of “Karakkaze,” a type of local wind in Japan, was conducted. First, winter days under a winter-type synoptic pressure pattern with daily minimum relative humidity of less than 40% were classified according to strong wind (wind speed = 9 ms¡1, Karakkaze day), medium wind (6 ms¡1 5 wind speed < 9 ms¡1), and weak wind (wind speed < 6 ms¡1). Secondly, the spatial patterns of the surface wind in each category are confirmed by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA)-Automated Meteorological Data Acquisition System (AMeDAS) observation data. In addition, we compared the boundary-layer wind of the three categories using wind speed data from the obser- vation tower of the Meteorological Research Institute (MRI) in Tsukuba and from the JMA wind profiler in Kumagaya. Finally, we performed one-dimensional numerical experiments using a column Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL) model to evaluate the impact of solar radiation and upper-level wind on the formation of the Karakkaze. The results are summarized as follows. On the strong-wind days, strong northwesterly winds appear in the area along the Arakawa River and the Tonegawa River from Maebashi. -

Junior Year at Tsukuba Program 2020-2021

University of Tsukuba Tsukuba Science City, Japan Junior Year at Tsukuba Program 2020 2021 Junior Year at Tsukuba Program 2020 2021 Message from the President Contents 1 Message from the President 2 University of Tsukuba and Tsukuba Science City 4 International Exchange 8 Junior Year at Tsukuba Program (JTP) In today's increasingly competitive world 10 with its rapid economic and political Financial Aid changes, it is extremely important for the 11 international community to foster mutual General Information for International Students understanding among peoples of different countries. 12 Program Details Offering courses in English since its beginning in 1995, our Junior Year at 20 Tsukuba Program (JTP) has hosted Map hundreds of international students who have been eager to study in Japan. It is not necessary for you to be uent in Japanese to participate in the program, and yet you can take great advantage of cultural and Kyosuke NAGATA academic opportunities that are unavailable at your home university. President, University of Tsukuba In order to assist you with your study of the Japanese language, culture, science, and technology, the JTP currently offers a 2020-2021 Academic Calendar variety of courses in English. And when your Japanese becomes well advanced Each Semester consists of Module A, B&C, and each module has five weeks. through our Japanese language program, you are encouraged to take regular courses with Japanese students. Then your choice Spring Semester (April – September) of courses will be enormous. I would like to Classes Begin 6 April extend these benets to you. I look forward Final Exams (Module A&B) 29 June – 3 July to welcoming you to Tsukuba. -

Akita International University Global Review 2009

Publisher: Mineo Nakajima The Editorial Board Editor-in -Chief: Mineo Nakajima Managing Editor: Michio Katsumata Associate Editor: C. Kenneth Quinones Editorial Assistants: Yuka Okura, Fumi Ogasawara COPYRIGHT Ⓒ 2009 Akita International University Press ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means--graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution, or information storage and retrieval systems--without the written permission of the publisher. For permission to use material from this text, contact us by WEB: http://www.aiu.ac.jp FAX: +81-18-886-5912 PHONE: +81-18-886-5907 Publishing Office Akita International University Press Yuwa, Akita City, Japan 010-1292 Printed in Japan ISSN 1883-8243 ii ii CONTENTS Preface: Message from Mineo Nakajima, President, AIU EditorÕs Note: Michio Katsumata, Management Editor < B as i d u c at i > 1. Antinomies of Education and Their Resolution in Liberal Arts Marcin Schroeder, Dean of Academic Affairs 13 Publisher: Mineo Nakajima <GLOBAL ISSUES> 2. Analyzing a Strategy for Development Finance Cooperation in Northeast The Editorial Board AsiaÓ Editor-in -Chief: Mineo Nakajima Takashi Yamamoto, Associate Professor at Global Business 17 1 Managing Editor: Michio Katsumata Associate Editor: C. Kenneth Quinones 3. JapanÕs Constitutional Pacifism between Collective Security and Collective Self- Defense Editorial Assistants: Yuka Okura, Fumi Ogasawara Tetsuya Toyoda, Lecturer at Global Studies 1519 COPYRIGHT Ⓒ 2009 Akita International University Press 4. The Economic Effect of Taiwanese Tourists on Akita 30 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or Yeh Tsung-Ming, Assistant Professor at Global Business 26 used in any form or by any means--graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution, or information storage and retrieval systems--without the written permission of the 5. -

Tsukuba Science City Area Shizuoka Central Area

Program endedinFY2007 Program endedinFY2007 ●Development Stage ●Development Stage IT Life Sciences (Fiscal Year 2005–2007) (Fiscal Year 2005–2007) Tsukuba Center, Inc Shizuoka Organization for Creation of Industries 2-1-6 Sengen, Tsukuba City, Ibaraki 305-0047 JAPAN Shizuokaken Sangyo Keizai Kaikan 4F, 44-1 Otemachi, Aoi-ku, TEL: +81-29-858-6000 Shizuoka City, Shizuoka 420-0853 JAPAN Tel: +81-54-254-4512 Tsukuba Science City Area Core Research Organizations Shizuoka Central Area Core Research Organizations Development of a Ubiquitous Visual-Information Surveillance System Creation of a food science business for overcoming lifestyle-related University of Tsukuba, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), University of Shizuoka, Shizuoka University, Tokai University, for Safe and Secure Urban Living National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) diseases caused by physical/mental stress Shizuoka Industrial Research Institute of Shizuoka Prefecture ● ● ● ● ● Industry…KDDI Corporation, Hitachi, Ltd., ADS Co., Ltd., and others ● ● Industry…Fuji Nihon Seito Corporation, Nihon Preventive Medical Laboratory. Co., Ltd., Prima Meat Packers Ltd., etc. ● ● Major Participating ● ● Major Participating ● ● Research Organizations Academia…University of Tsukuba ● ● Research Organizations Academia…University of Shizuoka, Shizuoka University, Tokai University ● ● ● ● Government…Shizuoka Industrial Research Institute of Shizuoka Prefecture, ● ● Government…National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) ● ● ● ● Shizuoka Prefectural Research Institute of Agriculture and Forestry, Shizuoka Swine & Poultry Experiment Station, and others ● Overview of Project Overview of Project Today, safety and security are strongly demanded by the public in all aspects of life, including the prevention of crime and maintenance This project aims to develop a stress sensor and foods that reduce physical/mental stress and prevent lifestyle-related diseases. -

![Access Map [ Wide-Area View ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2629/access-map-wide-area-view-3882629.webp)

Access Map [ Wide-Area View ]

Access Map [ Wide-area view ] ▶ Sendai to Tsukuba Kashiwa-Tanaka Sta. Joban Expressway Kashiwa I.C. 春日部 千 葉 Tsukuba 野 田 柏 ◀Tokyo Express Past the toll booth right direction (Kashiwa) towards. Route 16 Tokatsu Techno Plaza please turn right at the signal Syakenkan behind of Syakenkan. Japan National University of Tokyo Cancer CenterEeast Kashiwa Campus Access to the Porch Baseball Stadium or Delivery Entrance Sport Stadium Access to the Parking Lot Tsujinaka Hospital Park City Sawayaka Chiba Kashiwanoha Campus Kenmin Plaza Keiyo Bank 2nd Avenue National Research Kashiwanoha Institute of Police Science Kashiwa-no-ha P Conference Center Kashiwanoha Park Oak Village Kashiwanoha Kashiwanoha Campus Sta. University of Tokyo Chiba University LaLaport Kashiwa Ⅱ Campus Kashiwanoha Kashiwanoha Campus Kashiwanoha Park City HighSchool Kashiwanoha Campus to Akihabara [ Arriving by car ] About 2km from Chiba district Exit on national highway No.16, Joban Expressway "Kashiwa IC" With car navigation system: "Wakashiba 175, Kashiwa, Access to the Porch or Delivery Entrance Chiba Prefecture " or "Kashiwanoha campus station" turn right in front of the elevated [ Arriving by train ] Access to the Parking lot 1 min walk from Tsukuba Express“Kashiwanoha Campus Station” West Exit turn left ahead of Keiyo bank Tsujinaka Hospital [ Arriving from Narita Airport ] About 75-105 minutes by highway express bus to "Kashiwanoha Campus Station(In front of Mitsui Garden Hotel Kashiwa-no-ha“) [ Arriving from Haneda Airport ] About 75 minutes by highway express bus to Keiyo