Bahamas 2019 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commonwealth of the Bahamas General Elections

The Commonwealth of The Bahamas General Elections 10 May 2017 MAP OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF THE BAHAMAS ii The Bahamas General Election 10 May 2017 Table of Content Letter of Transmittal v Executive Summary viii Chapter 1 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Terms of Reference 1 Activities 1 Chapter 2 3 POLITICAL BACKGROUND 3 Background 3 Political Developments Leading up to the 2017 General Election 5 Chapter 3 6 ELECTORAL FRAMEWORK AND ELECTION ADMINISTRATION 6 Background 6 Legal Framework and Regional and International Commitments 6 Election Management Body 7 Delimitation of Boundaries 7 Eligibility and Registration of Electors 8 Candidate Eligibility and Nomination 8 Advance Voting 9 Complaints, Appeals and Election Petitions 9 Inclusive Participation and Representation 10 Women 10 Youth 11 Incapacitated Voters 11 Key Issues 12 Recommendation 16 Chapter 4 18 CAMPAIGN ENVIRONMENT AND MEDIA 18 Nature of the Campaign 18 The Police 18 The Media 19 Social Media 19 Campaign Financing 20 Recommendations 21 iii Chapter 5 22 VOTING, COUNTING AND RESULTS 22 Background 22 Key Procedures for Opening and Voting 22 Assessment of the Opening of the Polls and Voting 23 Key Procedures for Closing and Counting 24 Assessment of Closing and Counting 25 Parliamentary Results 26 Recommendations 26 ANNEX I: Biographies of Chairperson and Observers 26 ANNEX II: Deployment Plan 28 ANNEX III: Arrival Statement 29 ANNEX IV: Interim Statement 31 iv The Commonwealth Observer Group to the 2017 General Elections of The Commonwealth of The Bahamas Letter of Transmittal 14 May 2017 Dear Secretary-General, The Commonwealth Observer Group you deployed to observe the elections in the Commonwealth of The Bahamas held on 10 May 2017 is pleased to submit to you its final report. -

Reservation Package

THE BAHAMAS - SOUTHERN EXUMA CAYS RESERVATION PACKAGE Toll free 1 800 307 3982 | Overseas 1 250 285 2121 | [email protected] | kayakingtours.com SOUTHERN EXUMA CAYS EXPEDITION 5 NIGHTS / 6 DAYS SEA KAYAK EXPEDITION & BEACH CAMPING | GEORGE TOWN DEPARTURE Please read through this package of information to help you to prepare for your tour. Please also remember to return your signed medical information form as soon as possible and read and understand the liability waiver which you will be asked to sign upon arrival. We hope you are getting excited for your adventure! ITINERARY We are so glad that you will be joining us for this incred- which dry out at low tide. This makes it a great place ible adventure. This route will take us into the stunning for exploring by kayak as most boats cannot access Exuma Cays. The bountiful and rich wildlife (including this shallow area. Our destination for tonight is either colourful tropical fish, corals, sea turtles and many Long Cay (apx 7 miles) or Brigantine Cay (apx 9 miles). species of birds), long sandy beaches and clear blue Once there we will set up camp, snorkel and relax. water will help you to fall in love with the Bahamas. DAY 2 After breakfast we will pack up camp and continue DAY PRIOR exploring the Brigantine Cays. The Cays are home to Depart your home for the Bahamas today or earli- several different types of mangrove forests. If the tides er if you wish. There are direct flights from Toronto to are right we will paddle through some of these incred- George Town several days a week or if coming from ibly important and diverse ecosystems which are of- other locations, the easiest entry point is to arrive into ten nursery habitat for all sorts of fish species, small Nassau. -

PLP Wins Landslide Victory 29 Seats Give Powerful Mandate from the People the Progressive Liberal Party Under the Leadership of Mr

May 15th, 2002 The Abaconian Page 1 VOLUME 10, NUMBER 10, MAY 15th, 2002 PLP Wins Landslide Victory 29 Seats Give Powerful Mandate from the People The Progressive Liberal Party under the leadership of Mr. Perry Gladstone Christie won the May 2 election in a landslide, win- ning 29 seats of the 40 seat House of Assem- bly. The Free National Movement won seven seats and independents won four seats. The PLP had been out of power since 1992 when the FNM defeated them for the first time since the independence of The Bahamas. They had been in power for 25 years under the leadership of Sir Lynden O. Pindling. They now have won 21 of the 24 Nassau seats, three of the six Grand Bahama seats and five of the seats in the other Family Islands. Two candidates who had previously been cabinet ministers in the FNM government ran independently and won. They were Mr. Pierre Dupuch, former Minister of Agricul- ture and Fisheries, and Mr. Tennyson Well, former Attorney General. Mr. Christie was sworn in on May 3 in a ceremony of pomp and pageantry at Govern- ment House. He pledged to “build a peace- ful, prosperous and just society for all our people.” He is the third prime minister since The Bahamas became an independent coun- try in 1973. He has already named his cabinet mem- Winner of the general election held on May 2, Mr. Perry Christie of the Progressive Liberal Party quickly organized his new bers and created two new ministries. Still to government and began his task of governing. -

Marina Status: Open with Exceptions

LATEST COVID-19 INFORMATION BRILAND CLUB MARINA HARBOUR ISLAND, THE BAHAMAS UPDATED AUGUST 6, 2021 MARINA STATUS: OPEN WITH EXCEPTIONS Effective Friday, August 6, 2021, those persons applying for a travel health visa to enter The Bahamas or travel within The Bahamas will be subjected to the following new testing requirements: Entering The Bahamas Vaccinated Travelers All fully vaccinated travelers wishing to enter The Bahamas will now be required to obtain a COVID-19 test (Rapid Antigen Test or PCR), with a negative result, within five days of arrival in The Bahamas. Unvaccinated Travelers There are no changes to the testing requirements for unvaccinated persons wishing to enter The Bahamas. All persons, who are 12 years and older and who are unvaccinated, will still be required to obtain a PCR test taken within five days of arrival in The Bahamas. Children and Infants All children, between the ages of 2 and 11, wishing to enter The Bahamas will now be required to obtain a COVID-19 test (Rapid Antigen Test or PCR), with a negative result, within five days of arrival in The Bahamas. All children, under the age of 2, are exempt from any testing requirements. Once in possession of a negative COVID-19 RT-PCR test and proof of full vaccination, all travelers will then be required to apply for a Bahamas Health Travel Visa at travel.gov.bs (click on the International Tab) where the required test must be uploaded. LATEST COVID-19 INFORMATION BRILAND CLUB MARINA HARBOUR ISLAND, THE BAHAMAS UPDATED AUGUST 6, 2021 Traveling within The Bahamas Vaccinated Travelers All fully vaccinated travelers wishing to travel within The Bahamas, will now be required to obtain a COVID-19 test (Rapid Antigen Test or PCR), with a negative result, within five days of the travel date from the following islands: New Providence, Grand Bahama, Bimini, Exuma, Abaco and North and South Eleuthera, including Harbour Island. -

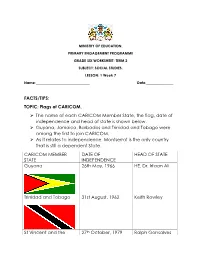

Flags of CARICOM. the Name of Each CARICOM

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION. PRIMARY ENGAGEMENT PROGRAMME GRADE SIX WORKSHEET: TERM 2 SUBJECT: SOCIAL STUDIES. LESSON: 1 Week 7 Name:______________________________ Date:_______________ FACTS/TIPS: TOPIC: Flags of CARICOM. The name of each CARICOM Member State, the flag, date of independence and head of state is shown below. Guyana, Jamaica, Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago were among the first to join CARICOM. As it relates to independence, Montserrat is the only country that is still a dependent State. CARICOM MEMBER DATE OF HEAD OF STATE STATE INDEPENDENCE Guyana 26th May, 1966 HE. Dr. Irfaan Ali Trinidad and Tobago 31st August, 1962 Keith Rowley St Vincent and the 27th October, 1979 Ralph Gonsalves Grenadines Dominica 3rd November,1978 Roosevelt Skerrit Bahamas 10th July,1973 Hubert Minnis Jamaica 6th August,1962 Andrew Holness St Lucia 22nd February,1979 Allen Michael Chastanet Belize 21stSeptember,1981 Dean Barrow Montserrat British Dependency Joseph.T.E.Farrell St Kitts and Nevis 19th September,1983 Timothy Harris Haiti 1st January,1804 Jovenel Moise Grenada 17th February,1984 Keith Mitchell Suriname 25th November,1975 Chan Santokhi Barbados 30th November, 1966 Mia Mottley Antigua and Barbuda 1st November 1981 Gaston Browne Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) was established: Located in Trinidad and Tobago, the CCJ Settles all CSME related disputes and acts as the final Court of Appeal for civil and criminal matters from courts within CARICOM member states. CARICOM Passports were established: CARICOM passports make intra-regional and international travel easier for citizens of CARICOM member states. The three colours of the passports are: dark blue for civilians green for government officials red for diplomats. -

Roberts: Idbfinanced Survey Good News for Christie Today's Fr

4/29/2015 The Nassau Guardian Date: Sign Up Subscribe Advertise About Us Contact Archives search... Search News Business National Review Opinion Sports OpEd Editorial Letters Lifestyles Religion Obituaries Health & Wellness Education Pulse Arts & Culture Spice 2014 Hurricane Supplement Home & Fashion Today's News WEATHER The Abacos Light Rain Max: 91°F | Min: 78°F Roberts: IDBfinanced survey good news for Christie CANDIA DAMES Print Managing Editor [email protected] Outlook Published: Apr 14, 2015 Gmail PrintFriendly In light of the customary “midterm blues” among voters, the results of an InterAmerican Development Share This: Twitter Bank (IDB)financed survey reported on in National Facebook Review yesterday are “very good news” for Prime Minister Perry Christie and “very bad news” for Rate this article: Tumblr Opposition Leader Dr. Hubert Minnis, according to More... (293) Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) Chairman Bradley Add To Favourite Roberts. Settings... The results showed that 9.5 percent of those surveyed viewed Christie’s job performance as “very good” AddThis Privacy and 37.4 percent as “good”. The results show that 9.6 percent viewed Christie’s job performance as “very bad”. Today's Front Page Another 11.3 percent viewed it as “bad”. 32.2 percent said Christie’s job performance was neither good nor bad, but “fair”. National Review also revealed that more than 45 percent of the Bahamians surveyed said they would vote for a candidate or party different from the current administration if an election were held this week. Another 24.5 percent said they would not vote at all. -

US Department of Commerce , 2006

Doing Business In The Bahamas: A Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2006 . ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. • Chapter 1: Doing Business In … • Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment • Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services • Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment • Chapter 5: Trade Regulations and Standards • Chapter 6: Investment Climate • Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing • Chapter 8: Business Travel • Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events • Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services 4/20 /2007 Chapter 1: Doing Business In The Bahamas • Market Overview • Market Challenges • Market Opportunities • Market Entry Strategy Market Overview Return to top • The Bahamas offers potential investors a stable democratic environment, relief from personal and corporate income taxes, timely repatriation of corporate profits, and proximity to the United States with extensive air and communication link s, and a good pool of skilled professionals. The Bahamas is a member of the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI), Canada’s CARIBCAN Program, and the European Union’s LOME IV Agreement. The Bahamas officially welcomes foreign investment in tourism, banking, agricultural and industrial areas that generate local employment, especially white -collar or skilled jobs. The vast majority of successful foreign investments, however, have remained in the areas of tourism and banking. The Government reserves retail and wholesale outlets, non - specialty restaurants, most construction projects, and many small businesses exclusively for Bahamians. • Nearly 60% of The Bahamas’ Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is derived from tourism. Financial services constitute the second most important sector of the economy and accounts for up to 15% of GDP. -

The Bahamas 2018

FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2018 The Bahamas 91 FREE /100 Political Rights 38 /40 Civil Liberties 53 /60 LAST YEAR'S SCORE & STATUS 91 /100 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview The Bahamas are a stable democracy where political rights and civil liberties are generally respected. However, the islands have a relatively high homicide rate, and migrants do not always receive due process under the law. Key Developments in 2017 • The opposition Free National Movement (FNM) party won general elections held in May, and FNM leader Hubert Minnis became the new prime minister. • A wave of harsh immigration raids took place after Minnis announced a December 31 deadline for irregular migrants to obtain regular status. • Rights groups reported that a number of migrants were detained without being granted access to legal counsel, and that many of their cases were not heard by a judge within the legally required 48 hours. • A long-awaited Freedom of Information Act was approved, but it lacked some key provisions, including whistleblower protections. Political Rights A. Electoral Process A1 0-4 pts Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 The Bahamas are governed under a parliamentary system, and the governor general is appointed by the British monarch as head of state. The prime minister is head of government, and is appointed by the governor general; the office is usually held by the leader of the largest party in parliament or head of a parliamentary coalition. -

Review of Queen Conch

unuftp.is Final Project 2017 REVIEW OF QUEEN CONCH (Lobatus gigas) SAMPLING EFFORTS IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF THE BAHAMAS Indira Nyoka Brown Science and Conservation Unit Ministry of Agriculture and Marine Resources P. O. Box N-3028, East Bay Street, Nassau, The Bahamas [email protected] Supervisor(s): Supervisors: Jónas Páll Jónasson, Julian M. Burgos [email protected] [email protected] Marine and Freshwater Research Institute, Reykjavík, Iceland ABSTRACT Recognising the commercial importance of the queen conch fishery, increasing fishing effort, and high demand in international trade for resources, there are concerns about the long-term sustainability of queen conch stocks throughout The Bahamas. The objective of this study was to review the sampling efforts of queen conch in The Bahamas and evaluate the precision of the estimates when reducing the sample. Analyses were performed to quantify the spatial coverage of previous surveys. Permutation analyses were carried out on mean abundance to evaluate the precision of the estimates when reducing the sample efforts on three size classes of queen conch, from survey sites in the Ragged Island and the Jumentos Cays; Sandy Point, Abaco, and Mores Island, Abaco. The results suggested that sampling effort can slightly be reduced to expand the survey area or reallocate effort in areas that have not been surveyed. The total surveyed area was estimated at a total of 3,567 km². The total habitat of queen conch was estimated at an approximate size of 11,888 km². The layers comprised of two previously identified queen conch habitats and queen conch surveyed areas that were obtained from The Nature Conservancy - Northern Caribbean Division, Community Conch and FAO. -

Communiqué Issued at the Conclusion of the Twenty-Ninth Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community

COMMUNIQUÉ ISSUED AT THE CONCLUSION OF THE TWENTY-NINTH INTER-SESSIONAL MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF HEADS OF GOVERNMENT OF THE CARIBBEAN COMMUNITY 26-27 February 2018, Port-au-Prince, Haiti The Twenty-Ninth Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) was held at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, on 26-27 February 2018. The President of Haiti, His Excellency Jovenel Moïse, Chaired the proceedings. Other Members of the Conference in attendance were Prime Minister of The Bahamas, Honourable Dr. Hubert Minnis; Prime Minister of Barbados, Rt. Honourable Freundel Stuart; Prime Minister of Grenada, Dr. the Rt. Honourable Keith Mitchell; Prime Minister of Jamaica, the Most Honourable Andrew Holness; Prime Minister of Saint Lucia, Honourable Allen Chastanet; Prime Minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Dr. the Honourable Ralph Gonsalves; and Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Dr. the Honourable Keith Rowley. Antigua and Barbuda was represented by His Excellency Ambassador Colin Murdoch; Belize was represented by Senator the Honourable Michael Peyrefitte, Attorney General; Dominica was represented by the Honourable Francine Baron, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Guyana was represented by His Excellency Vice President Carl Greenidge; Montserrat was represented by the Honourable Delmaude Ryan, Deputy Premier and Minister of Education, Health, Youth Affairs, Sports and Social Services; St Kitts and Nevis was represented by the Honourable Vance Amory, Senior Minister; Suriname was represented by His Excellency Vice-President, Michael Ashwin Adhin. Associate Members in attendance were British Virgin Islands represented by Dr. the Hon Kedrick Pickering, Deputy Premier; the Turks and Caicos Islands represented by Hon. -

Capability Document

BHM CO. LTD Capability Document providing infrastructure and construction solutions since 1984 Contents Welcome Our Heritage We recognise that better access to improved infrastructure services is an BHM was founded in 1984 by a group of like minded Bahamian businessmen who remain with the Company to this day; all the founders have construction backgrounds. The Company has had a very successful operating history and important engine for economic growth. The condition of infrastructure can be a key has evolved into a diversified group of businesses specialising in civil engineering (airports, roads and marine ports), construction projects (warehouses, luxury homes and infrastructure works) and a very strong electrical division to bottleneck to growth in the Bahamas and many Caribbean countries. support all of our projects. Welcome to BHM Company Ltd - a new improvement works or emergency and Our Vision scheduled maintenance. For many years, the Our Vision is to develop a sustainable business focused on local and personalised service backed by world-class future for your construction, improvement leadership and technical delivery for airports, marine ports and trunk roads in growing economies. BHM is committed to and maintenance works for airports, roads, BHM Group has consistently enjoyed praise leading the way in complex civil engineering and construction projects. marine and mining facilities. BHM is a dynamic for a well-earned reputation of delivering company with a long established proven track quality results within budget and record for the successful delivery of major on schedule. BHM gains client confidence by civil engineering and infrastructure projects in providing a consistent service and added value growing economies. -

The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 40 Number 3 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 40, Article 3 Issue 3 1961 The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were Thelma Peters Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Peters, Thelma (1961) "The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 40 : No. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol40/iss3/3 Peters: The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were THE AMERICAN LOYALISTS IN THE BAHAMA ISLANDS: WHO THEY WERE by THELMA PETERS HE AMERICAN LOYALISTS who moved to the Bahama Islands T at the close of the American Revolution were from many places and many walks of life so that classification of them is not easy. Still, some patterns do emerge and suggest a prototype with the following characteristics: a man, either first or second gen- eration from Scotland or England, Presbyterian or Anglican, well- educated, and “bred to accounting.” He was living in the South at the time of the American Revolution, either as a merchant, the employee of a merchant, or as a slave-owning planter. When the war came he served in one of the volunteer provincial armies of the British, usually as an officer.