Nebraska Fossils Which Excite Common Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering the Mother of All Bison Researchers Trace Bison to Common Ancestor, Pinpoint Arrival in North America

Discovering the mother of all bison Researchers trace bison to common ancestor, pinpoint arrival in North America. By Katie Willis on March 13, 2017 Unlike other notorious invaders such as zebra mussels, bison were not introduced by humans. But their rapid spread and diversification are hallmarks of an invasive species. Scientists from University of Alberta have pinpointed when bison “The DNA was too degraded, but as techniques have developed, first appeared in North America and learned more about their in particular new ways to 'fish out' bison DNA from the mixture of family tree, thanks to new fossils and genetic tools. bacterial and other DNA in these bones, these have allowed us to piece together these genome sequences,” explains Shapiro. New research by Duane Froese and Alberto Reyes in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences has identified The group showed that DNA of the earliest Yukon bison was North America’s oldest bison fossils and applied new techniques similar to DNA from a giant long-horned bison, called Bison for ancient DNA extraction to clarify the earliest parts of the bison latifrons, which was excavated in Colorado. family tree. “Bison latifrons is an interesting beast,” says Froese. “Its horns Froese and his colleagues worked with paleogeneticists to measured more than two metres across at the tips and it was sequence the mitochondrial genomes of more than 40 bison, perhaps 25% larger than modern bison.” including the two oldest bison fossils ever recovered: one from Ch’ijee’s Bluff in the Vuntut Gwitchin Territory in northern Yukon, The Colorado fossil was well-dated and only 10,000 to 20,000 and another from Snowmass, Colorado. -

Agate Fossil Beds

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 1980 Agate Fossil Beds Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark "Agate Fossil Beds" (1980). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 160. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/160 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Agate Fossil Beds cap. tfs*Af Clemson Universit A *?* jfcti *JpRPP* - - - . Agate Fossil Beds Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Nebraska Produced by the Division of Publications National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 1980 — — The National Park Handbook Series National Park Handbooks, compact introductions to the great natural and historic places adminis- tered by the National Park Service, are designed to promote understanding and enjoyment of the parks. Each is intended to be informative reading and a useful guide before, during, and after a park visit. More than 100 titles are in print. This is Handbook 107. You may purchase the handbooks through the mail by writing to Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC 20402. About This Book What was life like in North America 21 million years ago? Agate Fossil Beds provides a glimpse of that time, long before the arrival of man, when now-extinct creatures roamed the land which we know today as Nebraska. -

Middle Miocene Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction of the Central Great Plains from Stable Carbon Isotopes in Large Mammals Willow H

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of Sciences 7-2017 Middle Miocene Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction of the Central Great Plains from Stable Carbon Isotopes in Large Mammals Willow H. Nguy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss Part of the Geology Commons, Paleobiology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Nguy, Willow H., "Middle Miocene Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction of the Central Great Plains from Stable Carbon Isotopes in Large Mammals" (2017). Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 91. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss/91 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MIDDLE MIOCENE PALEOENVIRONMENTAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE CENTRAL GREAT PLAINS FROM STABLE CARBON ISOTOPES IN LARGE MAMMALS by Willow H. Nguy A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Under the Supervision of Professor Ross Secord Lincoln, Nebraska July, 2017 MIDDLE MIOCENE PALEOENVIRONMENTAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE CENTRAL GREAT PLAINS FROM STABLE CARBON ISOTOPES IN LARGE MAMMALS Willow H. Nguy, M.S. University of Nebraska, 2017 Advisor: Ross Secord Middle Miocene (18-12 Mya) mammalian faunas of the North American Great Plains contained a much higher diversity of apparent browsers than any modern biome. -

Morton County, Kansas Michael Anthony Calvello Fort Hays State University

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Master's Theses Graduate School Summer 2011 Mammalian Fauna From The ulF lerton Gravel Pit (Ogallala Group, Late Miocene), Morton County, Kansas Michael Anthony Calvello Fort Hays State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Calvello, Michael Anthony, "Mammalian Fauna From The ulF lerton Gravel Pit (Ogallala Group, Late Miocene), Morton County, Kansas" (2011). Master's Theses. 135. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses/135 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. - MAMMALIAN FAUNA FROM THE FULLERTON GRAVEL PIT (OGALLALA GROUP, LATE MIOCENE), MORTON COUNTY, KANSAS being A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Fort Hays State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Michael Anthony Calvello B.A., State University of New York at Geneseo Date Z !J ~4r u I( Approved----c-~------------- Chair, Graduate Council Graduate Committee Approval The Graduate Committee of Michael A. Calvello hereby approves his thesis as meeting partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Master of Science. Approved: )<--+-- ----+-G~IJCommittee Meilnber Approved: ~J, iii,,~ Committee Member 11 ABSTRACT The Fullerton Gravel Pit, Morton County, Kansas is one of many sites in western Kansas at which the Ogallala Group crops out. The Ogallala Group was deposited primarily by streams flowing from the Rocky Mountains. Evidence of water transport is observable at the Fullerton Gravel Pit through the presence of allochthonous clasts, cross-bedding, pebble alignment, and fossil breakage and subsequent rounding. -

The Flaxville Gravel and ·Its Relation to Other Terrace Gravels of the Northern Great Plains

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary . -UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Professional Paper 108-J THE FLAXVILLE GRAVEL AND ·ITS RELATION TO OTHER TERRACE GRAVELS OF THE NORTHERN GREAT PLAINS BY ARTHUR J. COLLIER AND W. T. THOM, JR. Published January 26,1918 Shorter contributions to general geology, 1917 ( Paates 179-184 ) WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1918 i, '!· CONTENTS. Page. Introduction ............... ~ ... ~ ........... , ........... .......... ~ ......................... ~ .... -.----- 179 Flaxville gravel ......................................................................· .. ............ ·.... 179 Late Pliocene or early Pleistocene gravel. ..................................... ..... .. .................• - 182 Late Pleistocene and Recent erosion and deposition ........................ ..... ............ ~ ............ 182 Oligocene beds in Cypress Hilla .................... .' ................. ........................ .......... 183 Summary ....•......................... ················· · ·· · ·········.···············"···················· 183 ILLUSTRA 'fl ONS. Page. PLATE LXII. Map of northeastern Montana and adjacent parts of Canada, showing the distribution of erosion levels and gravel horizons................................................................ 180 J,XIII. A, Surface of the Flaxville plateau, northeastern Montana; B, Outcrop of cemented Flaxville gravel in escarpment ·of plateau northwest of Opheim, Mont.; C; Escarpment of the Flaxville plateau, northeastern -

Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America SERIES PUBLICATIONS of the SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the H^arine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that refXJrt the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the worid. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. Press requirements for manuscript and art preparation are outlined on the inside back cover. -

Multivariate Discriminant Function Analysis of Camelid Astragali

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org A method for improved identification of postcrania from mammalian fossil assemblages: multivariate discriminant function analysis of camelid astragali Edward Byrd Davis and Brianna K. McHorse ABSTRACT Character-rich craniodental specimens are often the best material for identifying mammalian fossils to the genus or species level, but what can be done with the many assemblages that consist primarily of dissociated postcrania? In localities lacking typi- cally diagnostic remains, accurate identification of postcranial material can improve measures of mammalian diversity for wider-scale studies. Astragali, in particular, are often well-preserved and have been shown to have diagnostic utility in artiodactyls. The Thousand Creek fauna of Nevada (~8 Ma) represents one such assemblage rich in postcranial material but with unknown diversity of many taxa, including camelids. We use discriminant function analysis (DFA) of eight linear measurements on the astragali of contemporaneous camelids with known taxonomic affinity to produce a training set that can then be used to assign taxa to the Thousand Creek camelid material. The dis- criminant function identifies, at minimum, four classes of camels: “Hemiauchenia”, Alforjas, Procamelus, and ?Megatylopus. Adding more specimens to the training set may improve certainty and accuracy for future work, including identification of camelids in other faunas of similar age. For best statistical practice and ease of future use, we recommend using DFA rather than qualitative analyses of biplots to separate and diag- nose taxa. Edward Byrd Davis. University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History and Department of Geological Sciences, 1680 East 15th Avenue, Eugene, Oregon 97403. [email protected] Brianna K. -

Name-Bearing Fossil Type Specimens and Taxa Named from National Park Service Areas

Sullivan, R.M. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2016, Fossil Record 5. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 73. 277 NAME-BEARING FOSSIL TYPE SPECIMENS AND TAXA NAMED FROM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AREAS JUSTIN S. TWEET1, VINCENT L. SANTUCCI2 and H. GREGORY MCDONALD3 1Tweet Paleo-Consulting, 9149 79th Street S., Cottage Grove, MN 55016, -email: [email protected]; 2National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division, 1201 Eye Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20005, -email: [email protected]; 3Bureau of Land Management, Utah State Office, 440 West 200 South, Suite 500, Salt Lake City, UT 84101: -email: [email protected] Abstract—More than 4850 species, subspecies, and varieties of fossil organisms have been named from specimens found within or potentially within National Park System area boundaries as of the date of this publication. These plants, invertebrates, vertebrates, ichnotaxa, and microfossils represent a diverse collection of organisms in terms of taxonomy, geologic time, and geographic distribution. In terms of the history of American paleontology, the type specimens found within NPS-managed lands, both historically and contemporary, reflect the birth and growth of the science of paleontology in the United States, with many eminent paleontologists among the contributors. Name-bearing type specimens, whether recovered before or after the establishment of a given park, are a notable component of paleontological resources and their documentation is a critical part of the NPS strategy for their management. In this article, name-bearing type specimens of fossil taxa are documented in association with at least 71 NPS administered areas and one former monument, now abolished. -

Ancient Bison (Bison Antiquus)

Ancient bison (Bison antiquus) The ancient bison grazed in the valleys eating grasses, shrubs and woody plants. Ancient bison became extinct about 10,000 years ago. The ancient bison is the ancestor of today’s bison. Ancient bison traveled in herds or groups. What is the name of another animal that traveled in herds? 2345 Searl Parkway, Hemet, CA 92543 www.WesternScienceCenter.org “Yesterday’s” camel (Camelops hesternus) The “Yesterday’s” camel is very closely related to today’s living Ilama. Camels originally lived in North America 50 million years ago before spreading to other parts of the world. “Yesterday’s” camel is now extinct. Camels are herbivores and eat lots of grasses. Unlike camels that live today “Yesterday’s” camel may have liked to eat leafy forest plants. Why do scientists with the Diamond Valley Lake project think “Yesterday’s” camel lived in herds or large groups? 2345 Searl Parkway, Hemet, CA 92543 www.WesternScienceCenter.org Dire wolf (Canis dirus) Fossils of the dire wolf were found while digging the Diamond Valley Lake project. This extinct wolf was as big as the gray wolf that lives today. The jaws and large teeth of the dire wolf were the most powerful of all the wolves. This would help them catch their food. The dire wolf became extinct about 11,000 years ago. The word "dire" means “grim.” Why do you think this wolf was named "dire" wolf? 2345 Searl Parkway, Hemet, CA 92543 www.WesternScienceCenter.org Western horse (Equus occidentalis) The Western horse lived in large herds or groups. They were as tall as today’s Arabian horse. -

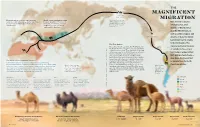

Magnificent Migration

THE MAGNIFICENT Land bridge 8 MY–14,500 Y MIGRATION Domestication of camels began between World camel population today About 6 million years ago, 3,000 and 4,000 years ago—slightly later than is about 30 million: 27 million of camelids began to move Best known today for horses—in both the Arabian Peninsula and these are dromedaries; 3 million westward across the land Camelini western Asia. are Bactrians; and only about that connected Asia and inhabiting hot, arid North America. 1,000 are Wild Bactrians. regions of North Africa and the Middle East, as well as colder steppes and Camelid ancestors deserts of Asia, the family Camelidae had its origins in North America. The The First Camels signature physical features The earliest-known camelids, the Protylopus and Lamini E the Poebrotherium, ranged in sizes comparable to of camels today—one or modern hares to goats. They appeared roughly 40 DMOR I SK million years ago in the North American savannah. two humps, wide padded U L Over the 20 million years that followed, more U L ; feet, well-protected eyes— O than a dozen other ancestral members of the T T O family Camelidae grew, developing larger bodies, . E may have developed K longer legs and long necks to better browse high C I The World's Most Adaptable Traveler? R ; vegetation. Some, like Megacamelus, grew even I as adaptations to North Camels have adapted to some of the Earth’s most demanding taller than the woolly mammoths in their time. LEWSK (Later, in the Middle East, the Syrian camel may American winters. -

Quaternary and Late Tertiary of Montana: Climate, Glaciation, Stratigraphy, and Vertebrate Fossils

QUATERNARY AND LATE TERTIARY OF MONTANA: CLIMATE, GLACIATION, STRATIGRAPHY, AND VERTEBRATE FOSSILS Larry N. Smith,1 Christopher L. Hill,2 and Jon Reiten3 1Department of Geological Engineering, Montana Tech, Butte, Montana 2Department of Geosciences and Department of Anthropology, Boise State University, Idaho 3Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Billings, Montana 1. INTRODUCTION by incision on timescales of <10 ka to ~2 Ma. Much of the response can be associated with Quaternary cli- The landscape of Montana displays the Quaternary mate changes, whereas tectonic tilting and uplift may record of multiple glaciations in the mountainous areas, be locally signifi cant. incursion of two continental ice sheets from the north and northeast, and stream incision in both the glaciated The landscape of Montana is a result of mountain and unglaciated terrain. Both mountain and continental and continental glaciation, fl uvial incision and sta- glaciers covered about one-third of the State during the bility, and hillslope retreat. The Quaternary geologic last glaciation, between about 21 ka* and 14 ka. Ages of history, deposits, and landforms of Montana were glacial advances into the State during the last glaciation dominated by glaciation in the mountains of western are sparse, but suggest that the continental glacier in and central Montana and across the northern part of the eastern part of the State may have advanced earlier the central and eastern Plains (fi gs. 1, 2). Fundamental and retreated later than in western Montana.* The pre- to the landscape were the valley glaciers and ice caps last glacial Quaternary stratigraphy of the intermontane in the western mountains and Yellowstone, and the valleys is less well known. -

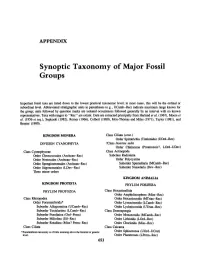

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida