Construction of a Time-Variant Poverty Index for Costa Rica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESTUDIO DE Puriscal 1. BASES Fllosoficas, DESARROLLO Y ESTADO ACTUAL DE LA INVESTIGACION APLICADA EN NUTRICION

Rev. Med. Hosp. Na!. Nií'losCosta Rica 17 (1 Y 2); 1-2'0,1982 ESTUDIO DE PURISCAl 1. BASES FllOSOFICAS, DESARROLLO y ESTADO ACTUAL DE LA INVESTIGACION APLICADA EN NUTRICION Leonardo Mata* INTRODUCCION Antes de 1975 no existía en Costa Rica ninguna institución Que se encargase del estudio sistemático de problemas prioritarios en el campo de la salud humana. Preocupado por esa situación, el Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas (CONICIT), nombró una comisión nacional para Que se abocara al estudio de ese problema. La comisión concluyó en 1974 Que era necesario la or ganización de un Instituto que agrupase investigadores interesados en el estudio multidisciplinario de problemas de salud humana que no se estaban investigando en el país. La Universidad de Costa Rica acogió la iniciativa del CONtCIT y creó en 1975 un Programa de Investigaciones en Salud (1NISAL adscrito a las Faculta des del Area de Salud. En el INISA se identificó como prioritarias la salud del niño y de la mujer en la etapa de procreación, por ser este binomio uno de los más vulnerables a las agresiones del medio, especialmente social. Se identifcaron problemas nutricio nales, infecciosos, congénitos, genéticos y degenerativos como aquellos que debían recibir inmediata atención. Finalmente, se creyó fundamental investigar y cono cer más los determinantes sociales de la enfermedad, particularmente la "patología social", a fin de establecer recomendaciones para corregir o mejorar situaciones prevalecientes. Con el fin de desarrollar un programa coherente de trabajo en fa investigación en salud, con repercusiones en la enseñanza y en la acción social, se planificó un "estudio longitudinal", esto es, un programa prospectivo a largo plazo que permi tiese la observaci6n por períodos largos de poblaciones humanas en su ecosistema natural. -

Distritos Declarados Zona Catastrada.Xlsx

Distritos de Zona Catastrada "zona 1" 1-San José 2-Alajuela3-Cartago 4-Heredia 5-Guanacaste 6-Puntarenas 7-Limón 104-PURISCAL 202-SAN RAMON 301-Cartago 304-Jiménez 401-Heredia 405-San Rafael 501-Liberia 508-Tilarán 601-Puntarenas 705- Matina 10409-CHIRES 20212-ZAPOTAL 30101-ORIENTAL 30401-JUAN VIÑAS 40101-HEREDIA 40501-SAN RAFAEL 50104-NACASCOLO 50801-TILARAN 60101-PUNTARENAS 70501-MATINA 10407-DESAMPARADITOS 203-Grecia 30102-OCCIDENTAL 30402-TUCURRIQUE 40102-MERCEDES 40502-SAN JOSECITO 502-Nicoya 50802-QUEBRADA GRANDE 60102-PITAHAYA 703-Siquirres 106-Aserri 20301-GRECIA 30103-CARMEN 30403-PEJIBAYE 40104-ULLOA 40503-SANTIAGO 50202-MANSIÓN 50803-TRONADORA 60103-CHOMES 70302-PACUARITO 10606-MONTERREY 20302-SAN ISIDRO 30104-SAN NICOLÁS 306-Alvarado 402-Barva 40504-ÁNGELES 50203-SAN ANTONIO 50804-SANTA ROSA 60106-MANZANILLO 70307-REVENTAZON 118-Curridabat 20303-SAN JOSE 30105-AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 30601-PACAYAS 40201-BARVA 40505-CONCEPCIÓN 50204-QUEBRADA HONDA 50805-LIBANO 60107-GUACIMAL 704-Talamanca 11803-SANCHEZ 20304-SAN ROQUE 30106-GUADALUPE O ARENILLA 30602-CERVANTES 40202-SAN PEDRO 406-San Isidro 50205-SÁMARA 50806-TIERRAS MORENAS 60108-BARRANCA 70401-BRATSI 11801-CURRIDABAT 20305-TACARES 30107-CORRALILLO 30603-CAPELLADES 40203-SAN PABLO 40601-SAN ISIDRO 50207-BELÉN DE NOSARITA 50807-ARENAL 60109-MONTE VERDE 70404-TELIRE 107-Mora 20307-PUENTE DE PIEDRA 30108-TIERRA BLANCA 305-TURRIALBA 40204-SAN ROQUE 40602-SAN JOSÉ 503-Santa Cruz 509-Nandayure 60112-CHACARITA 10704-PIEDRAS NEGRAS 20308-BOLIVAR 30109-DULCE NOMBRE 30512-CHIRRIPO -

Zonificación De Riesgo Por Hechos Delictivos En El Cantón Central De San José

Rev. Ciencias Sociales 116: 133-143 / 2007 (II) ISSN: 0482-5276 ZONIFICACIÓN DE RIESGO POR HECHOS DELICTIVOS EN EL CANTÓN CENTRAL DE SAN JOSÉ Marcela Chaves Álvarez* Mario Segnini Boza** REsumEN Utilizando los datos sobre denuncias de robos de vehículos y asaltos en el cantón central de San José, se hace una clasificación de riesgo para las vías de esa zona. El análisis demuestra que el riesgo de un asalto es más concentrado en el centro urbano, mientras que el riesgo por robo de vehículos es más alto en los barrios residenciales periféricos. La distribución horario demuestra que, excepto en domingo, cuando se nota una ligera disminución, todos los días son igualmente peligrosos para estos dos tipos de actos delictivos, especialmente entre las seis y las nueve de la noche. PALABRAS CLAVE: San JOSÉ , CR * ROBOS * AsalTOS * ZOniFicaciÓN DE riESGO AbsTracT Using data on robberies and car theft in San José, maps of potentially risky areas are drawn. Analysis shows that the risk of robbery is higher in the center of the city while the risk of car theft is higher in the residential areas around San José. The hour distribution shows that every day, except for a small decline on Sundays, is equally risky for both types of delinquency, specially between six and nine o’clock in the evening. KEY WORDS: San JOSÉ , CR * RObbEriES * THEFT * RisK assEssmENT 1. ANTECEDENTES Y JusTIFicaciÓN abordado por Castillo (1980) principalmente con estudios enfocados a explicar las condicio- En los últimos años el país ha experimen- nes socioeconómicas y familiares que propician tado un palpable aumento de la criminalidad, el crecimiento de las conductas violentas en sobre todo, en las zonas urbanas. -

Ocean Governance in Costa Rica

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT OCEAN GOVERNANCE IN COSTA RICA An Overview on the Legal and Institutional Framework in Ocean Affairs © 2019, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development This work is available open access by complying with the Creative Commons licence created for intergovernmental organizations, available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designation employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. UNCTAD/DITC/TED/INF/2018/4 AN OVERVIEW ON THE LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK IN OCEAN AFFAIRS iii Contents Figures, Tables and Boxes ......................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................iv Acronyms and abbreviations ....................................................................................................................v Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... -

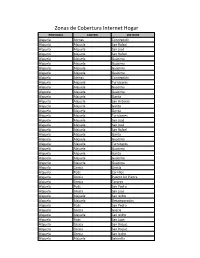

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

Codigo Nombre Dirección Regional Circuito Provincia

CODIGO NOMBRE DIRECCIÓN REGIONAL CIRCUITO PROVINCIA CANTON 0646 BAJO BERMUDEZ PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE ACOSTA 0614 JUNQUILLO ARRIBA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0673 MERCEDES NORTE PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0645 ELOY MORUA CARRILLO PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0689 JOSE ROJAS ALPIZAR PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0706 RAMON BEDOYA MONGE PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0612 SANTA CECILIA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0615 BELLA VISTA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0648 FLORALIA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0702 ROSARIO SALAZAR MARIN PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0605 SAN FRANCISCO PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0611 BAJO BADILLA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0621 JUNQUILLO ABAJO PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0622 CAÑALES ARRIBA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL JUAN LUIS GARCIA 0624 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL GONZALEZ 0691 SALAZAR PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL DARIO FLORES 0705 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL HERNANDEZ 3997 LICEO DE PURISCAL PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 4163 C.T.P. DE PURISCAL PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL SECCION NOCTURNA 4163 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL C.T.P. DE PURISCAL 4838 NOCTURNO DE PURISCAL PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL CNV. DARIO FLORES 6247 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL HERNANDEZ LICEO NUEVO DE 6714 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL PURISCAL 0623 CANDELARITA PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0679 PEDERNAL PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0684 POLKA PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0718 SAN MARTIN PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0608 BAJO LOS MURILLO PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0626 CERBATANA PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0631 -

SOUTHERN COSTA RICA 367 Parque Internacional La Amistad Reserva Indígena Boruca Cerro Chirripó Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary Los Quetzales Parque Nacional

© Lonely Planet Publications 366 lonelyplanet.com 367 SOUTHERN COSTA RICA Southern Costa Rica In southern Costa Rica, the Cordillera de Talamanca descends dramatically into agricultural lowlands that are carpeted with sprawling plantations of coffee beans, bananas and Afri- can palms. Here, campesinos (farmers) work their familial lands, maintaining an agricultural tradition that has been passed on through the generations. While the rest of Costa Rica adapts to the recent onslaught of package tourism and soaring foreign investment, life in the southern zone remains constant, much as it has for centuries. In a country where little pre-Columbian influence remains, southern Costa Rica is where you’ll find the most pronounced indigenous presence. Largely confined to private reservations, the region is home to large populations of Bribrí, Cabécar and Boruca, who are largely succeed- ing in maintaining their traditions while the rest of the country races toward globalization. Costa Rica’s well-trodden gringo trail seems to have bypassed the southern zone, though this isn’t to say that the region doesn’t have any tourist appeal. On the contrary, southern Costa Rica is home to the country’s single largest swath of protected land, namely Parque Internacional La Amistad. Virtually unexplored, this national park extends across the border into Panama and is one of Central America’s last true wilderness areas. And while Monteverde is the country’s most iconic cloud forest, southern Costa Rica offers many equally enticing opportunities to explore this mystical habitat. If you harbor any hope of spotting the elusive resplendent quetzal, you can start by looking in the cloud forest in Parque Nacional Los Quetzales. -

2018-19 District 4240 Global Grant Initiative

2018-19 DISTRICT 4240 GLOBAL GRANT INITIATIVE “TIRRASES COMMUNITY DENTAL CLINIC” “DISEASE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT” “ECONOMIC AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT” “MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH” 2nd Draft-2018-19 Costa Rica GG-1571 GLOBAL GRANT- TIRRASES COMMUNITY DENTAL CLINIC REGION: CENTRAL AMERICA | COUNTRY: COSTA RICA | LOCATION: TIRRASES, CURRIDABAT, SAN JOSE. ROTARY AREAS OF FOCUS: DISEASE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT | ECONOMIC AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT | MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH (and ADULT & ELDERLY DENTAL HEALTH). ROTARY HOST PARTNERS: SAN PEDRO CURRIDABAT ROTARY CLUB - DISTRICT 4240 COSTA RICA. PARTNERING CLUBS AND OTHER ENTITIES: LEWISVILLE MORNING ROTARY CLUB, DENTON NOON ROTARY CLUB - DISTRICT 5790 TEXAS, SOUTHWEST AIRLINES, ROTARACTS AND INTERACTS, FUNDACION CURRIDABAT, AWOW INTERNATIONAL GIRLS LEADERSHIP INITIATIVE, CLINICA DENTAL LOMA VERDE, MUNICIPALITY GOVERNMENT OF CURRIDABAT, CAMPBELL & WILLIAMS FAMILY, DENTAL OF HIGHLAND VILLAGE -TX, MEHARRY MEDICAL COLLEGE, AND FISK UNIVERSITY, NASHVILLE TN. PLANNING COUNCIL (PC)- SAN PEDRO CURRIDABAT ROTARY CLUB - DISTRICT 4240 COSTA RICA, LEWISVILLE MORNING ROTARY CLUB, DENTON NOON ROTARY CLUB - DISTRICT 5790 TEXAS, SOUTHWEST AIRLINES, MEHARRY SCHOOL OF DENTISTRY, CAMPBELL & WILLIAMS DENTAL FOUNDATION, CLINICA DENTAL LOMA VERDE, SIGNED BY DRA. AYLIN SANCHEZ, FACULTY OF DENTISTRY UCR SIGNED BY DR. RONALD DE LA CRUZ, DR. ANDRES DE LA CRUZ “ORTHODONTICS” JEFFREY SIEBERT. DDS PC: WILL HOST A SERIES OF CONFERENCE CALLS AND PLANNING MEETINGS WITH MEMBERS OF DISTRICT 5790, DISTRICT 4240, STUDENT RESIDENTS, UNIVERSITY FACULTY, AND DENTAL PROFESSIONAL. SERVICE PROJECT VISIT: BY ROTARIANS, INTERACT, ROTARACT, COMMUNITY LEADERS, AND VOLUNTEERS. SOUTHWEST AIRLINES: PROVIDE AIRLINE TICKETS AND CARGO SPACE FOR THE EQUIPMENT. OVERVIEW: IN THE FALL OF 2017 A NEED ASSESSMENT WAS COMPLETED. AND AS A RESULT, A PILOT PROJECT WAS LAUNCHED. -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Gobierno Anuncia Nueva Fase De Reaperturas Y Actualización En Alertas

26 de junio 2020 GOBIERNO ANUNCIA NUEVA FASE DE REAPERTURAS Y ACTUALIZACIÓN EN ALERTAS • Cantones en zona amarilla, con algunas excepciones, podrán avanzar a fase 3 a partir de hoy a media noche. • Se excluye de esta disposición a Ulloa (Heredia), La Uruca, La Merced, Hospital, Hatillo, Mata Redonda, Catedral, Zapote, San Rafael de Escazú, Curridabat, San Francisco de Don Ríos, San Sebastián, Aserrí, San Gabriel, Corralillo (Cartago). • Distritos en alerta naranja permanecerán en fase 2. • La CNE actualizó la alerta naranja en los cantones de Upala, San Carlos, Pococí y Desamparados. • El Aeropuerto Internacional Juan Santamaría y el Daniel Oduber de Liberia podrán abrir el 1 de agosto. Luego de un análisis de la situación epidemiológica, Costa Rica podrá avanzar a la fase 3 de reapertura, con la excepción de las zonas en alerta naranja y algunos cantones y distritos aledaños. Así lo anunciaron en conferencia de prensa, el ministro de Salud, Daniel Salas y la ministra de Planificación Nacional y coordinadora del equipo económico, Pilar Garrido. Podrán avanzar a fase 3 a partir de hoy a media noche, los cantones y distritos en alerta amarilla, exceptuando a Ulloa (Heredia), La Uruca, La Merced, Hospital, Hatillo, Mata Redonda, Catedral, Zapote, San Rafael de Escazú, Curridabat, San Francisco de Don Ríos, San Sebastián, Aserrí, San Gabriel, Corralillo. Se les permitirá: • Fines de semana: Funcionamiento de fines de semana de tiendas (aforo de 50%), cines, teatros y museos al 50% (compra previa y separación de 1,8 metros). • Lunes a domingo: Se autoriza el funcionamiento de lugares de culto con un máximo de 75 personas y distanciamiento de 1.8 metros, según los protocolos aprobados. -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

Central America

Zone 1: Central America Martin Künne Ethnologisches Museum Berlin The paper consists of two different sections. The first part has a descriptive character and gives a general impression of Central American rock art. The second part collects all detailed information in tables and registers. I. The first section is organized as follows: 1. Profile of the Zone: environments, culture areas and chronologies 2. Known Sites: modes of iconographic representation and geographic context 3. Chronological sequences and stylistic analyses 4. Documentation and Known Sites: national inventories, systematic documentation and most prominent rock art sites 5. Legislation and institutional frameworks 6. Rock art and indigenous groups 7. Active site management 8. Conclusion II. The second section includes: table 1 Archaeological chronologies table 2 Periods, wares, horizons and traditions table 3 Legislation and National Archaeological Commissions table 4 Rock art sites, National Parks and National Monuments table 5 World Heritage Sites table 6 World Heritage Tentative List (2005) table 7 Indigenous territories including rock art sites appendix: Archaeological regions and rock art Recommended literature References Illustrations 1 Profile of the Zone: environments, culture areas and chronologies: Central America, as treated in this report, runs from Guatemala and Belize in the north-west to Panama in the south-east (the northern Bridge of Tehuantepec and the Yucatan peninsula are described by Mr William Breen Murray in Zone 1: Mexico (including Baja California)). The whole region is characterized by common geomorphologic features, constituting three different natural environments. In the Atlantic east predominates extensive lowlands cut by a multitude of branched rivers. They cover a karstic underground formed by unfolded limestone.