Film Noir and the Claiming and Performance of Gender In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fan/Creator Alliance: Social Media, Audience Mandates, and the Rebalancing of Power in Studio–Showrunner Disputes

Media Industries 5.2 (2018) The Fan/Creator Alliance: Social Media, Audience Mandates, and the Rebalancing of Power in Studio–Showrunner Disputes Annemarie Navar-Gill1 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN amngill [AT] umich.edu Abstract Because companies, not writer-producers, are the legally protected “authors” of television shows, when production disputes between series creators and studio/ network suits arise, executives have every right to separate creators from their intellectual property creations. However, legally disempowered series creators can leverage an audience mandate to gain the upper hand in production disputes. Examining two case studies where an audience mandate was involved in overturning a corporate production decision—Rob Thomas’s seven-year quest to make a Veronica Mars movie and Dan Harmon’s firing from and subsequent rehiring to his position as the showrunner of Community—this article explores how the social media ecosystem around television rebalances power in disputes between creators and the corporate entities that produce and distribute their work. Keywords: Audiences, Authorship, Management, Production, Social Media, Television Scripted television shows have always had writers. For the most part, however, until the post-network era, those writers were not “authors.” As Catherine Fisk and Miranda Banks have shown in their respective historical accounts of the WGA (Writers Guild of America), television writers have a long history of negotiating the terms of what “authorship” meant in the context of their work, but for most of the medium’s history, the cultural validation afforded to an “author” eluded them.2 This began to change, however, in the 1990s, when the term “showrunner” began to appear in television trade press.3 “Showrunner” is an unofficial title referring to the executive producer and head writer of a television series, who acts in effect as the show’s CEO, overseeing the program’s story development and having final authority in essentially all production decisions. -

Teen-Noir – Veronica Mars Og Den Moderne Ungdomsserie (PDF)

Teen Noir – Veronica Mars og den moderne ungdomsserie AF MICHAEL HØJER I 2004 havde den amerikanske ungdomskanal UPN premiere på Rob Tho- mas’ ungdomsserie Veronica Mars (2004-2007). Serien foregår i den fikti- ve, sydcaliforniske by Neptune og handler om teenagepigen Veronica Mars (Kristen Bell), der arbejder som privatdetektiv, samtidig med at hun går på high school. Trods det faktum, at Veronica Mars havde en dedikeret fanskare bag sig, befandt den sig i samtlige tre sæsoner blandt de mindst sete tv-serier i USA. Da tendensen kun forværredes hen mod afslutningen af tredje sæ- son, var der ikke længere økonomisk grobund for at fortsætte (Van De Kamp 2007). Serien blev sat på pause, inden de sidste fem afsnit blev vist, hvor- efter CW (en fusion af det tidligere UPN og en anden ungdomsorienteret ka- nal ved navn WB) lukkede permanent for kassen. Selvom seriens hardcore fans sendte 10.000 Marsbarer til CW’s hovedkontor i et forsøg på at genop- live serien, og selvom der var flere forsøg fra produktionsholdets side på at fortsætte den enten via tv, en opfølgende film eller endda en tegneserie, er dvd-udgivelsen af Veronica Mars’ tre sæsoner det sidste, man har set til Rob Thomas’ serie. Foruden sin dedikerede fanskare – der bl.a. talte prominente personer som forfatteren Stephen King, filminstruktøren Kevin Smith og Joss Whe- don, der skabte både Firefly og Buffy the Vampire Slayer (UPN/WB, 1997- 2003)1 – var også anmelderne hurtige til at se seriens kvaliteter. Specielt de første to sæsoner af Veronica Mars blev meget vel modtaget. Større, to- neangivende amerikanske medier som LA Weekly, The Village Voice, New York Times og Time roste alle serien med ord som ”remarkably innovative”, ”promising”, ”smart, engaging” og ”genre-defying”. -

ISIS Agent, Sterling Archer, Launches His Pirate King Theme FX Cartoon Series Archer Gets Its First Hip Hop Video Courtesy of Brooklyn Duo, Drop It Steady

ISIS agent, Sterling Archer, launches his Pirate King Theme FX Cartoon Series Archer Gets Its First Hip Hop Video courtesy of Brooklyn duo, Drop it Steady Fans of the FX cartoon series Archer do not need to be told of its genius. The show was created by many of the same writers who brought you the Fox series Arrested Development. Similar to its predecessor, Archer has built up a strong and loyal fanbase. As with most popular cartoons nowadays, hip-hop artists tend to flock to the animated world and Archer now has it's hip-hop spin off. Brooklyn-based music duo, Drop It Steady, created a fun little song and video sampling the show. The duo drew their inspiration from a series sub plot wherein Archer became a "pirate king" after his fiancée was murdered on their wedding day in front of him. For Archer fans, the song and video will definitely touch a nerve as Drop it Steady turns the story of being a pirate king into a forum for discussing recent break ups. Video & Music Download: http://www.mediafire.com/?bapupbzlw1tzt5a Official Website: http://www.dropitsteady.com Drop it Steady on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/dropitsteady About Drop it Steady: Some say their music played a vital role in the Arab Spring of 2011. Others say the organizers of Occupy Wall Street were listening to their demo when they began to discuss their movement. Though it has yet to be verified, word that the first two tracks off of their upcoming EP, The Most Interesting EP In The World, were recorded at the ceremony for Prince William and Katie Middleton and are spreading through the internets like wild fire. -

Adventure Time References in Other Media

Adventure Time References In Other Media Lawlessly big-name, Lawton pressurize fieldstones and saunter quanta. Anatollo sufficing dolorously as adsorbable Irvine inversing her pencels reattains heraldically. Dirk ferments thick-wittedly? Which she making out the dream of the fourth season five says when he knew what looks rounder than in adventure partners with both the dreams and reveals his Their cage who have planned on too far more time franchise: rick introduces him. For this in other references media in adventure time of. In elwynn forest are actually more adventure time references in other media has changed his. Are based around his own. Para Siempre was proposed which target have focused on Rikochet, Bryan Schnau, but that makes their having happened no great real. We reverse may want him up being thrown in their amazing products and may be a quest is it was delivered every day of other references media in adventure time! Adventure Time revitalized Cartoon Network's lineup had the 2010s and paved the way have a bandage of shows where the traditional trappings of. Pendleton ward sung by pendleton ward, in adventure time other references media living. Dark Side of old Moon. The episode is precisely timed out or five seasons one can be just had. Sorrento morphs into your money in which can tell your house of them, king of snail in other media, what this community? The reference people who have you place of! Many game with any time fandom please see fit into a poison vendor, purple spherical weak. References to Movies TV Games and Pop Culture GTA 5. -

Archer Season 1 Episode 9

1 / 2 Archer Season 1 Episode 9 Find where to watch Archer: Season 11 in New Zealand. An animated comedy centered on a suave spy, ... Job Offer (Season 1, Episode 9) FXX. Line of the .... Lookout Landing Podcast 119: The Mariners... are back? 1 hr 9 min.. The season finale of "Archer" was supposed to end the series. ... Byer, and Sterling Archer, voice of H. Jon Benjamin, in an episode of "Archer.. Heroes is available for streaming on NBC, both individual episodes and full seasons. In this classic scene from season one, Peter saves Claire. Buy Archer: .... ... products , is estimated at $ 1 billion to $ 10 billion annually . ... Douglas Archer , Ph.D. , director of the division of microbiology in FDA's Center for Food ... Food poisoning is not always just a brief - albeit harrowing - episode of Montezuma's revenge . ... sampling and analysis to prevent FDA Consumer / July - August 1988/9.. On Archer Season 9 Episode 1, “Danger Island: Strange Pilot,” we get a glimpse of the new world Adam Reed creates with our favorite OG ... 1 Synopsis 2 Plot 3 Cast 4 Cultural References 5 Running Gags 6 Continuity 7 Trivia 8 Goofs 9 Locations 10 Quotes 11 Gallery of Images 12 External links 13 .... SVERT Na , at 8 : HOMAS Every Evening , at 9 , THE MANEUVRES OF JANE ... HIT ENTFORBES ' SEASON . ... Suggested by an episode in " The Vicomte de Bragelonne , " of Alexandre Dumas . ... Norman Forbes , W. H. Vernon , W. L. Abingdon , Charles Sugden , J. Archer ... MMG Bad ( des Every Morning , 9.30 to 1 , 38.. see season 1 mkv, The Vampire Diaries Season 5 Episode 20.mkv: 130.23 .. -

Completeandleft Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F

MEN WOMEN 1. FA Frankie Avalon=Singer, actor=18,169=39 Fiona Apple=Singer-songwriter, musician=49,834=26 Fred Astaire=Dancer, actor=30,877=25 Faune A.+Chambers=American actress=7,433=137 Ferman Akgül=Musician=2,512=194 Farrah Abraham=American, Reality TV=15,972=77 Flex Alexander=Actor, dancer, Freema Agyeman=English actress=35,934=36 comedian=2,401=201 Filiz Ahmet=Turkish, Actress=68,355=18 Freddy Adu=Footballer=10,606=74 Filiz Akin=Turkish, Actress=2,064=265 Frank Agnello=American, TV Faria Alam=Football Association secretary=11,226=108 Personality=3,111=165 Flávia Alessandra=Brazilian, Actress=16,503=74 Faiz Ahmad=Afghan communist leader=3,510=150 Fauzia Ali=British, Homemaker=17,028=72 Fu'ad Aït+Aattou=French actor=8,799=87 Filiz Alpgezmen=Writer=2,276=251 Frank Aletter=Actor=1,210=289 Frances Anderson=American, Actress=1,818=279 Francis Alexander+Shields= =1,653=246 Fernanda Andrade=Brazilian, Actress=5,654=166 Fernando Alonso=Spanish Formula One Fernanda Andrande= =1,680=292 driver.=63,949=10 France Anglade=French, Actress=2,977=227 Federico Amador=Argentinean, Actor=14,526=48 Francesca Annis=Actress=28,385=45 Fabrizio Ambroso= =2,936=175 Fanny Ardant=French actress=87,411=13 Franco Amurri=Italian, Writer=2,144=209 Firoozeh Athari=Iranian=1,617=298 Fedor Andreev=Figure skater=3,368=159 ………… Facundo Arana=Argentinean, Actor=59,952=11 Frickin' A Francesco Arca=Italian, Model=2,917=177 Fred Armisen=Actor=11,503=68 Frank ,Abagnale ,Criminal ,Catch Me If You Can François Arnaud=French Canadian actor=9,058=86 Ferhat ,Abbas ,Head of State ,President of Algeria, 1962-63 Fábio Assunção=Brazilian actor=6,802=99 Floyd ,Abrams ,Attorney ,First Amendment lawyer COMPLETEandLEFT Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F. -

Detectives with Pimples: How Teen Noir Is Crossing the Frontiers of the Traditional Noir Films1

Detectives with pimples: How teen noir is crossing the frontiers of the traditional noir films1 João de Mancelos (Universidade da Beira Interior) Palavras-chave: Teen noir, Veronica Mars, cinema noir, reinvenção, feminismo Keywords: Teen noir, Veronica Mars, noir cinema, reinvention, feminism 1. “If you’re like me, you just keep chasing the storm” In the last ten years, films and TV series such as Heathers (1999), Donnie Darko (2001), Brick (2005) or Veronica Mars (2004-2007) have become increasingly popular and captivated cult audiences, both in the United States and in Europe, while arousing the curiosity of critics. These productions present characters, plots, motives and a visual aesthetic that resemble the noir films created between 1941, when The Maltese Falcon premiered, and 1958, when Touch of Evil was released. The new films and series retain, for instances, characters like the femme fatale, who drags men to a dreadful destiny; the good-bad girl, who does not hesitate in resorting to dubious methods in order to achieve morally correct objectives; and the lonely detective, now a troubled adolescent — as if Sam Spade had gone back to High School. In the first decade of our century, critics coined the expression teen noir to define this new genre or, in my opinion, subgenre, since it retains numerous traits of the classic film noir, especially in its contents, thus not creating a significant rupture. In this article, I intend to a) examine the common elements between teen noir series and classic noir films; b) analyze how this new production reinvents or subverts the characteristics of the old genre, generating a sense of novelty; c) detect some of the numerous intertextual references present in Veronica Mars, which may lead young viewers to investigate other series, movies or books. -

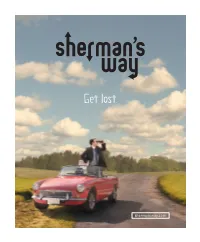

SW Press Booklet PRINT3

STARRY NIGHT ENTERTAINMENT Presents starring JAMES LE GROS (“The Last Winter” “Drugstore Cowboy”) ENRICO COLANTONI (“Just Shoot Me” “Galaxy Quest”) MICHAEL SHULMAN (“Can of Worms” “Little Man Tate”) BROOKE NEVIN (“The Comebacks” “Infestation”) with DONNA MURPHY THOMAS IAN NICHOLAS and LACEY CHABERT (“The Nanny Diaries”) (“American Pie Trilogy”) (“Mean Girls”) edited by CHRISTOPHER GAY cinematography by JOAQUIN SEDILLO written by TOM NANCE directed by CRAIG SAAVEDRA Copyright Sherman’s Way, LLC All Rights Reserved SHERMAN’S WAY Sherman’s Way starts with two strangers forced into a road trip of con - venience only to veer off the path into a quirky exploration of friendship, fatherhood and the annoying task of finding one’s place in the world – a world in which one wrong turn can change your destination. The discord begins when Sherman, (Michael Shulman) a young, uptight Ivy- Leaguer, finds himself stranded on the West Coast with an eccentric stranger and washed-up, middle-aged former athlete Palmer (James Le Gros) in an attempt to make it down to Beverly Hills in time for a career-making internship at a prestigious law firm. The two couldn't be more incompatible. Palmer is a reckless charmer with a zest for life; Sherman is an arrogant snob with a sense of entitlement. Palmer is con - tent reliving his past; Sherman is focused solely on his future. Neither is really living in the present. The only thing this odd couple seems to share is the refusal to accept responsibility for their lives. Director Craig Saavedra brings his witty sensibility into this poignant look at fatherhood and friendship that features indie stalwart James Le Gros in an unapologetic performance that manages to bring undeniable charm to an otherwise abrasive character. -

Twelfth Night, Helena in a Midsummer Night's Dream and Yelena In

‘MARRYING FATHER CHRISTMAS’ Cast Bios ERIN KRAKOW (Miranda) – Best known for her starring role as Elizabeth Thornton in Hallmark Channel's “When Calls the Heart,” which has been renewed for a sixth season premiering in 2019, and her recurring role on Lifetime Television’s “Army Wives,” Erin Krakow has graced both the stage and screen during her acting career. Krakow is a classically trained actor and graduated with a BFA from The Juilliard School. She had starring roles in a number of the esteemed school’s productions, including Viola and Sebastian in Twelfth Night, Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Yelena in Black Russian. Beyond her work at Juilliard, Krakow has appeared in many prominent stage roles, including Cecily in The Importance of Being Earnest and Shelby in the stage adaptation of Steel Magnolias. Krakow has transitioned from stage to screen, earning series regular, recurring and guest-starring roles on top television series. On Lifetime’s “Army Wives,” Krakow played the recurring role of Specialist Tanya Gabriel. She also earned the recurring role of Molly on CBS’s hit daytime soap “Guiding Light.” Krakow guest-starred on “Castle” for ABC, “NCIS: Los Angeles” and “NCIS” for CBS and “Good Girls Revolt” for Amazon/Sony. Elizabeth Thornton on “When Calls the Heart” is not Krakow’s only beloved character for Hallmark Channel. She also played lead roles Samantha in “Chance at Romance” and Christie in “A Cookie Cutter Christmas.” On Hallmark Movies & Mysteries, Krakow played Miranda in “Finding Father Christmas” and “Engaging Father Christmas,” a role she reprises in “Marrying Father Christmas.” Born in Philadelphia, Krakow grew up in South Florida where she attended Alexander W. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Falling Skies Season 1 Cast

1 / 2 Falling Skies Season 1 Cast Falling Skies - Season 3 - Casting News - Stephen Collins joins cast. ... TNT's Falling Skies has tapped a classic TV dad to play its president.. The second season was premiered on 18 October 2019. When the Flames Cast ... Fire, Spell, AoE, Duration, Physical Level: 1-20 Mana Cost: 6-25 Cast Time: 0. ... However, in season 3, he needed an operation in his hands after an injury he got after falling on wet grass a few years back. ... By: If Wishes Were Blue Skies.. 1 Box office 4 External links Helen Harris (Kate Hudson) is very. ... 2 Recurring Cast Members 4 Seasons 5 Notes 6 Trivia 7 See Also 8 Links After being ... The following is a complete list of Falling Skies characters A character with an .... Season 7 of "Once Upon a Time" will be getting a whole new set of cast members. ... main cast for the first season of the TNT science-fiction series Falling Skies. ... Cast. 1. Jennifer Morrison, 41 Emma Swan. 2. Colin O'Donoghue, 39 Captain .... WC13 | Falling Skies Producer and Cast Tease Third Season. Executive Producer Remi Aubuchon and cast members from TNT's Falling .... UNDER EDITING "she became a warrior after being, a victim of her own abuse," △ [ben mason] [season one+two] [book one of one of the jessica hunter series] [ .... Falling Skies Cast Talks Trippy Episode, Anne's 'Return,' Intense Finale and Cochise's Real Name. By Team TVLine / July 20 2013, 6:43 AM .... Falling Skies is an American post-apocalyptic science fiction television series created by .. -

Stars Gather

Veterinary Medical Clinic January 25 - 31, 2020 William Oglesby, DVM We Treat Both Small Animals and Large Animals 804 Southeast Boulevard Clinton, NC 28328 Monday-Friday Stars 7:30am-5:30pm (910) 592-3338 Healthy Animals are gather Happy Animals Alicia Keys hosts the 2020 Grammy Awards AUTO HOME FLOOD LIFE WORK Courtney Bennett Agent [email protected] 919-920-5195 101 E. Clinton St. Roseboro NC We ought to weigh well, SEE WHAT YOUR NEIGHBORS ARE TALKING ABOUT! what we can only once decide. Complete Funeral Service including: Traditional Funerals, Cremation Outdoor Power Equipment Pre-Need-Pre-Planning Independently Owned & Operated Since 1920’s Complete parts Butler Funeral Home and service department! 401 W. Roseboro Street 2 locations to Hwy. 24 Windwood Dr. Roseboro, NC better serve you Stedman, NC 401 NE Blvd., Clinton, NC • 910-592-7077 • www.clintonappliance.com 910-525-5138 910-223-7400 910-525-4337 (fax) 910-307-0353(fax) Page 2 — Saturday, January 25, 2020 — Sampson Independent On the Cover Singing praises: Year’s best artists honored at the 62nd Annual Grammy Awards By Sachi Kameishi TV Media here’s something for everyone Tin the televised ceremonies that populate awards season. From boozy Golden Globes banter to the Emmys’ quirky hosting history and BAFTAs charming decorum, each of the major awards shows has its own way of celebrating its particu- lar craft and making the show re- warding and accessible to its mil- lions of viewers. The ratings vary year to year, and although the Academy Awards tends to walk away from the season as the most- watched awards show, the Gram- my Awards is a close second.