New Ways of Seeing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Creative Output of Alexej Von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864

The creative output of Alexej von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864 - Wiesbaden, Germany, 1941) is dened by a simultaneously visual and spiritual quest which took the form of a recurring, almost ritual insistence on a limited number of pictorial motifs. In his memoirs the artist recalled two events which would be crucial for this subsequent evolution. The rst was the impression made on him as a child when he saw an icon of the Virgin’s face reveled to the faithful in an Orthodox church that he attended with his family. The second was his rst visit to an exhibition of paintings in Moscow in 1880: “It was the rst time in my life that I saw paintings and I was touched by grace, like the Apostle Paul at the moment of his conversion. My life was totally transformed by this. Since that day art has been my only passion, my sancta sanctorum, and I have devoted myself to it body and soul.” Following initial studies in art in Saint Petersburg, Jawlensky lived and worked in Germany for most of his life with some periods in Switzerland. His arrival in Munich in 1896 brought him closer contacts with the new, avant-garde trends while his exceptional abilities in the free use of colour allowed him to achieve a unique synthesis of Fauvism and Expressionism in a short space of time. In 1909 Jawlensky, his friend Kandinsky and others co-founded the New Association of Artists in Munich, a group that would decisively inuence the history of modern art. Jawlensky also participated in the activities of Der Blaue Reiter [the Blue Rider], one of the fundamental collectives for the formulation of the Expressionist language and abstraction. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

Alexander Von Salzmann 1874 Tbilisi (Georgia) – 1934 Leysin (Switzerland)

Alexander von Salzmann 1874 Tbilisi (Georgia) – 1934 Leysin (Switzerland) A native of Tbilisi, Alexander von Salzmann was born into a cultivated family and received a thorough upbringing and early training in art, music and drama. Fluent in four languages – Russian, German, English and French – he was often described as sensitive and amiable but at the same time reputed to be unreliable and indolent. He trained as a painter in Moscow, later moving to Munich where he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in 1898 to study under Franz Stuck. Two years later, Wassily Kandinsky joined the same painting class. A large number of Russian artists were living and working in Munich around the turn of the twentieth century. Kandinsky, who had a strong network of contacts within Schwabing’s vibrant art world, introduced Salzmann to one of his many Russian contacts – the painter Alexej von Jawlensky. Jawlensky was romantically involved with Marianne von Werefkin, a Russian aristocrat and painter who had made the decision to interrupt her own artistic Alexander von Salzmann, Self-portrait, career to further Jawlensky’s painting. In her elegant Munich 1905 apartment Werefkin hosted a Salon which grew to be a hub of literary and artistic exchange. Salzmann soon became a regular visitor and before long was making advances to his hostess. Despite a significant age difference, they became lovers but the affair ended abruptly in 1905. Six years later Kandinsky, Jawlensky and Werefkin formed The Blue Rider, one of the leading artists’ groups of the twentieth century. Like many other Munich-based, emerging artists of the period Salzmann earned his living as an illustrator for the magazine Jugend. -

Max Beckmann Alexej Von Jawlensky Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Fernand Léger Emil Nolde Pablo Picasso Chaim Soutine

MMEAISSTTEERRWPIECREKSE V V MAX BECKMANN ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER FERNAND LÉGER EMIL NOLDE PABLO PICASSO CHAIM SOUTINE GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES V MASTERPIECES V GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS MAX BECKMANN KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE 6 STILLEBEN MIT WEINGLÄSERN UND KATZE 1929 STILL LIFE WITH WINE GLASSES AND CAT 16 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY STILLEBEN MIT OBSTSCHALE 1907 STILL LIFE WITH BOWL OF FRUIT 26 ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER LUNGERNDE MÄDCHEN 1911 GIRLS LOLLING ABOUT 36 MÄNNERBILDNIS LEON SCHAMES 1922 PORTRAIT OF LEON SCHAMES 48 FERNAND LÉGER LA FERMIÈRE 1953 THE FARMER 58 EMIL NOLDE BLUMENGARTEN G (BLAUE GIEßKANNE) 1915 FLOWER GARDEN G (BLUE WATERING CAN) 68 KINDER SOMMERFREUDE 1924 CHILDREN’S SUMMER JOY 76 PABLO PICASSO TROIS FEMMES À LA FONTAINE 1921 THREE WOMEN AT THE FOUNTAIN 86 CHAIM SOUTINE LANDSCHAFT IN CAGNES ca . 1923-24 LANDSCAPE IN CAGNES 98 KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE MAX BECKMANN oil on canvas Provenance 1946 Studio of the Artist 60 x 40,5 cm Hanns and Brigitte Swarzenski, New York 5 23 /8 x 16 in. Private collection, USA (by descent in the family) signed and dated lower right Private collection, Germany (since 2006) Göpel 71 2 Exhibited Busch Reisinger Museum, Cambridge/Mass. 1961. 20 th Century Germanic Art from Private Collections in Greater Boston. N. p., n. no. (title: Leaving the restaurant ) Kunsthalle, Mannheim; Hypo Kunsthalle, Munich 2 01 4 - 2 01 4. Otto Dix und Max Beckmann, Mythos Welt. No. 86, ill. p. 156. -

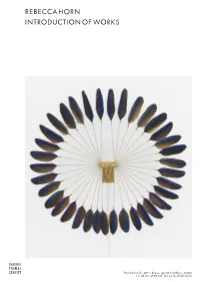

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

UNSEEN WORKS of the EUROPEAN AVANT-GARDE An

Press Release July 2020 Mitzi Mina | [email protected] | Melica Khansari | [email protected] | Matthew Floris | [email protected] | +44 (0) 207 293 6000 UNSEEN WORKS OF THE EUROPEAN AVANT-GARDE An Outstanding Family Collection Assembled with Dedication Over Four Decades To Be Offered at Sotheby’s London this July Over 40 Paintings, Sculpture & Works on Paper Led by a Rare Cubist Work by Léger & an Intimate Picasso Portrait of his Secret Lover Marie-Thérèse Pablo Picasso | Fernand Léger | Alberto Giacometti | Wassily Kandinsky | Lyonel Feininger | August Macke | Alexej von Jawlensky | Jacques Lipchitz | Marc Chagall | Henry Moore | Henri Laurens | Jean Arp | Albert Gleizes Helena Newman, Worldwide Head of Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Department, said: “Put together with passion and enjoyed over many years, this private collection encapsulates exactly what collectors long for – quality and rarity in works that can be, and have been, lived with and loved. Unified by the breadth and depth of art from across Europe, it offers seldom seen works from the pinnacle of the Avant-Garde, from the figurative to the abstract. At its core is an exceptionally beautiful 1931 portrait of Picasso’s lover, Marie-Thérèse, an intimate glimpse into their early days together when the love between the artist and his most important muse was still a secret from the world.” The first decades of the twentieth century would change the course of art history for ever. This treasure-trove from a private collection – little known and rarely seen – spans the remarkable period, telling its story through the leading protagonists, from Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti to Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger and Alexej von Jawlensky. -

“Uproar!”: the Early Years of the London Group, 1913–28 Sarah Macdougall

“Uproar!”: The early years of The London Group, 1913–28 Sarah MacDougall From its explosive arrival on the British art scene in 1913 as a radical alternative to the art establishment, the early history of The London Group was one of noisy dissent. Its controversial early years reflect the upheavals associated with the introduction of British modernism and the experimental work of many of its early members. Although its first two exhibitions have been seen with hindsight as ‘triumphs of collective action’,1 ironically, the Group’s very success in bringing together such disparate artistic factions as the English ‘Cubists’ and the Camden Town painters only underlined the fragility of their union – a union that was further threatened, even before the end of the first exhibition, by the early death of Camden Town Group President, Spencer Gore. Roger Fry observed at The London Group’s formation how ‘almost all artist groups’, were, ‘like the protozoa […] fissiparous and breed by division. They show their vitality by the frequency with which they split up’. While predicting it would last only two or three years, he also acknowledged how the Group had come ‘together for the needs of life of two quite separate organisms, which give each other mutual support in an unkindly world’.2 In its first five decades this mutual support was, in truth, short-lived, as ‘Uproar’ raged on many fronts both inside and outside the Group. These fronts included the hostile press reception of the ultra-modernists; the rivalry between the Group and contemporary artists’ -

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 the New Art Large Print Guide

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 12 April – 29 August 2016 The New Art Large Print Guide Please return to exhibition entrance The New Art 1 From 1969 several exhibitions in London and abroad presented conceptual art to wider public view. When Attitudes Become Form at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1969 or Seven Exhibitions at the Tate Gallery in 1972, for example, generated an institutional acceptance and confirmation for conceptual art. It was presented in such exhibitions in different contexts to encompass both an analytical or theoretical conceptual art largely based in language and philosophy, and one that was more inclusive and suggested an expansion of definitions of sculpture. This inclusive view of conceptual art underlines how it was understood as a set of strategies for formulating new approaches to art. One such approach was the increasing use of photography – first as a means of documentation and then recast and conceived as the work itself. Photography also provided a way for sculpture to free itself from objects and re-engage with reality. However, by the mid-1970s some artists were questioning not just the nature of art, but were using conceptual strategies to address what art’s function might be in terms of a social or political purpose. 2 1st Room Wall labels Clockwise from right of wall text John Hilliard born 1945 Camera Recording its Own Condition (7 Apertures, 10 Speeds, 2 Mirrors) 1971 70 photographs, gelatin silver print on paper on card on Perspex Here, Hilliard’s Praktica camera is both subject and object of the work. -

Claire Robins. Curious Lessons in the Museum: the Pedagogic Potential of Artists' Interventions

Bealby, M. S. (2014); Claire Robins. Curious lessons in the museum: the pedagogic potential of artists' interventions. Surrey 2013 Rosetta 16: 42 – 46 http://www.rosetta.bham.ac.uk/issue16/bealby2.pdf Claire Robins. Curious lessons in the museum: the pedagogic potential of artists' interventions. Surrey, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2013. Pp 260. £65.00. ISBN: 978-1-4094-3617-1 (Hbk). Reviewed by Marsia Sfakianou Bealby University of Birmingham In this publication, Claire Robins discusses art intervention within museums, through a series of 'curious' (in the sense of 'unusual') case-studies - hence the book title. 'Art intervention' is associated with 'conceptual art', i.e. art that stimulates critical thinking beyond traditional aesthetic values. As such, art intervention describes an interaction with a certain space, audience, or previously-existing artwork, in such a manner that their 'normality' is reassessed. A typical example of art intervention - provided by Robins in the introduction - is 'Sandwork' by Andy Goldsworthy.1 A large snake-like feature made from thirty tons of compacted sand, 'Sandwork' was exhibited at the British Museum in 1994, as part of the 'Time Machine' exhibition. The gigantic sculpture aimed at conceptually linking the past (Ancient Egyptian artefacts) with the present (contemporary art). Although there are many memorable examples of artwork provided in her book, it should be underlined that Robins does not merely focus on art. Rather, she places emphasis on the artists who practice art intervention, specifically exploring: i) how artists engage with museum collections through art intervention, ii) how artists contribute to museum education and curation via interventionist artworks, and iii) how art intervention can alter cultural and social 'status-quos' within, and beyond, the museum. -

Michael Craig-Martin B.1941 Untitled, 2000 Acrylic on Canvas 84 X 56 Inches 213.4 X 142.2 Cm

Michael Craig-Martin b.1941 Untitled, 2000 acrylic on canvas 84 x 56 inches 213.4 x 142.2 cm Provenance The Artist WaddingtonGalleries, London Sammlung Froehlich, Stuttgart Exhibitions London, Waddington Galleries, Michael Craig-Martin: Conference, 3May–3 June 2000 (ex-catalogue) Austria, Kunsthaus Bregenz, MichaelCraig-Martin: Signs of Life, 10 June–13 August 2006, illus colour p51 Description ‘My hope in the work is that by bringing certain objects together, you start to see connections, narratives, metaphors between some of them, and then the next one doesn’t fit the pattern, and you have to look again. I try to create as many threads of meaning as possible. But every one of them is at some point denied.’1 Rich with saturated colour, Untitled, 2000 is a striking example of Michael Craig-Martin’s iconic graphic style. Here, on a background of flat, vivid lilac, five seemingly incongruous motifs are united in a playful composition which collapses reference points such as scale, time and space. Craig-Martin first began making line drawings of ordinary objects in 1978 and he has continued this practice ever since. Early drawings were typically made in pencil in an A4 drawing pad, which he would then trace out onto sheets of acetate or drafting film with crepe tape (often black and sometimes red). However in the 1990s, having purchased his first computer, Craig-Martin stopped producing physical drawings, and instead began making them digitally as vector illustrations on a less sophisticated version of CAD, replacing his pencil with a mouse.2 This new method facilitated a greater degree of experimentation, enabling Craig-Martin to play around with the scale of an image, its orientation, colour and the thickness of the line with one click of a button. -

Conceptual Art & Minimalism

CONCEPTUAL ART AND MINIMALISM IN BRITAIN 1 QUESTIONS FROM LAST WEEK • Sarah Lucas lives with her partner, the artist, musician and poet Julian Simmons Artists Sarah Lucas (C) and Tracey Emin (R) attend The ICA Fundraising Gala held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts on March 29, 2011 in London, England. • Sarah Lucas now lives principally near Aldeburgh in Suffolk with her partner, the artist, musician and poet Julian Simmons, in the former bolthole of the composer Benjamin Britten and the tenor Peter Pears. She bought it as a weekend place with Sadie Coles in 2002. ‘I moved out there six years ago – it’s nice, impressive,’ she says curtly, before clamming up. ‘I don’t want people coming and snooping on me.’ (The Telegraph, 10 September 2013) • Benjamin Britain’s first house in Aldeburgh was Crag House on Crabbe Street overlooking the sea. He later moved to the Red House, Golf Lane, Aldeburgh which is now a Britten museum. 2 BRITISH ART SINCE 1950 1. British Art Since 1950 2. Pop Art 3. Figurative Art since 1950 4. David Hockney 5. Feminist Art 6. Conceptual Art & Minimalism 7. The Young British Artists 8. Video and Performance Art 9. Outsider Art & Grayson Perry 10.Summary 3 CONCEPTUAL ART • Conceptual Art. In the 1960s artists began to abandon traditional approaches and made ideas the essence of their work. These artists became known as Conceptual artists. Many of the YBA can be considered, and consider themselves, conceptual artists. That is, they regard the idea behind the work as important or more important than the work itself.