The Performance of Masculinity by the 'Artist'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today

The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today The Museum of Modern Art, New York August 01, 2010-November 01, 2010 6th Floor, Special Exhibitions, North Kunsthaus Zürich February 25, 2011-May 15, 2011 Sculpture in the Age of Photography 1. WILLIAM HENRY FOX TALBOT (British, 1800-1877) Bust of Patroclus Before February 7, 1846 Salt print from a calotype negative 7 x 6 5/16" on 8 7/8 x 7 5/16" paper (17.8 x 16 cm on 22.5 x 18.6 cm paper) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, 84.XP.921.2 2. ADOLPHE BILORDEAUX (French, 1807-1875) Plaster Hand 1864 Albumen silver print 12 1/16 x 9 3/8" (30.7 x 23.8 cm) Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris 3. LORRAINE O'GRADY (American, born 1934) Sister IV, L: Devonia's Sister, Lorraine; R: Nefertiti's Sister, Mutnedjmet from Miscegenated Family Album 1980/94 Silver dye bleach print 26 x 37" (66 x 94 cm) Courtesy the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York 4. CHARLES NÈGRE (French, 1820-1880) The Mystery of Death, Medallion by Auguste Préault November 1858 Photogravure 10 1/2 x 10 1/2" (26.6 x 26.7 cm) National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Purchased 1968 The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today - Exhibition Checklist Page 1 of 73 5. KEN DOMON (Japanese, 1909-1990) Right Hand of the Sitting Image of Buddha Shakyamuni in the Hall of Miroku, Muro-Ji, Nara 1942-43 Gelatin silver print 12 7/8 x 9 1/2" (32.7 x 24.2 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

Lehmannmaupin Lehmann Maupin

Robin Rhode, Proteus, 2020. C-print, 6 parts, each: 20.71 x 28.58 inches (52.6 x 72.6 cm) Overall: 43.39 x 89.68 inches (110.2 x 227.8 cm) Robin Rhode The Backyard is my World April 20 – June 6, 2021 Lehmann Maupin London #RobinRhode | @LehmannMaupin Lehmann Maupin London is pleased to present The Backyard is my World, an exhibition of work by South Africa-born, Berlin-based artist Robin Rhode. Working across (and often merging) media, including drawing, performance, street art, photography, and animation, Rhode is best-known for his serial photographs of his large-scale public wall drawings, in which figures interact with objects, vehicles, architecture, or abstract geometric shapes and patterns. Over the last two decades, Rhode has developed a distinct multidisciplinary body of work that engages numerous art historical influences, including graffiti, the minimal wall drawings of Sol Lewitt, 1970s performance art, and the stop-motion photography of Eadweard Muybridge. Rhode often draws from science, mathematics, history, artmaking, mythology, and politics to gain a deeper understanding of human beings and how they engage with the world that surrounds them. The Backyard is my World, the artist’s first solo exhibition in London since 2011, will feature photographs and animations produced over the last 10 years in a single location―the backyard of the artist's family home in Johannesburg, South Africa. In this exhibition, Rhode transforms the concrete surface of his backyard, turning it into a body of water, a mathematically inspired imaginary landscape, or a schoolyard playground. The yard functions as an outdoor studio of sorts, the concrete walls and ground offering a monochrome backdrop that transforms the flat visual plane into a three-dimensional space the artist activates using performers, found objects, and site-specific drawings. -

Robin Rhode: Animating the Everyday, Neuberger Museum of Art, NY

ROBIN RHODE 1976 Born Cape Town, South Africa Lives and works in Berlin, Germany 1998 Technikon Witwatersrand 2000 South African School of Film, Television, and Dramatic Art SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Memory is the Weapon, Kunsthalle Krems, Krems an der Donau 2019 Jericho, Stevenson, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Memory is the Weapon, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg The Broken Wall, Galerie Kamel Mennour, Paris 2018 A Plan of the Soul, Zurich Art Prize 2018, Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich The Geometry of Colour, Lehmann Maupin, New York 2017 Under the Sun, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv Paths and Fields, Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town Force of Circumstance, Kamel Mennour Gallery, Paris 2016 Primitives, Galeria Tucci Russo, Turin The Moon is Asleep, SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, GA 2015 The Sudden Walk, Kulturhuset, Stockholm Borne Frieze, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Recycled Matter, Stevenson Gallery, Johannesburg Drawing Waves, The Drawing Center, New York, NY 2014 Anima, Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv Having Been There, Lehmann Maupin, Hong Kong Tension, Tucci Russo Studio Per L’Arte Contemporanea, Turin Robin Rhode: Animating the Everyday, Neuberger Museum of Art, NY Robin Rhode: RHODE WORKS, Kunstmuseum Luzern, Lucerne 2013 The Call of Walls, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Paries Pictus, Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town Take Your Mind off the Street/Paries Pictus, Lehmann Maupin, NY 2012 Imaginary Exhibition, L&M Arts Los Angeles, CA 2011 Probables, (P) Fons Welters, Amsterdam 12b HaSharon St, Tel Aviv, Israel | www.bravermangallery.com -

2010 Newsletter

Number 46 – Summer 2010 NEWSLETTERAlumni INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS Contents From the Director . .3 New Faculty . .5 Honors: Philippe de Montebello and Thomas Mathews . 6 We’re on Facebook . 7 Alumni Voices Surrealism and a Parrot named Cacaloo . 8 Eternal Returns . 9 From Kalamazoo to Herstmonceux . .9 Applied Art History . 10 In Memoriam Dietrich von Bothmer . .11 James Wood . 12 Gerrit Lansing . 12 Colin Eisler Symposium . .13 Jonathan Alexander Retires . 13 Conferred PhDs . .13 Summer Stipends . 14 Commencement 2010 . .15 Outside Fellowships . 16 Faculty Updates . .17 Alumni Updates . .19 Alumni Donors . 34 Published by the Alumni Association of the Institute of Fine Arts 1 Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Association Officers: Board of Directors: Committees: Acting President Term ending April 1, 2011 Finance Committee: Valerie Hillings Gertje Utley Sabine Rewald Lisa Rotmil gutley@rcn .com sabine .rewald@metmuseum .org Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt Marie Tanner Phyllis Tuchman Treasurer marietanner@aol .com Lisa Rotmil Contributors: Marc Cincone lisarotmil@aol .com Term ending April 1, 2012 Suzanne Deal Booth Marcia Early Brocklebank Secretary Alicia Lubowski-Jahn Vivian Ebersman Cora Michael Alicia1155@aol .com Tom Freudenheim Cora .Michael@metmuseum .org Gertje Utley Jasper Gaunt Kathleen Heins gutley@rcn .com Keith Kelly Ex-Officio Shelley Rice Past Presidents Patricia Rubin Mary Tavener Holmes Phyllis Tuchman, Editor Connie Lowenthal History of the IFA Ida e . Rubin Julie Shean, Chair Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt Lisa Banner Helen Evans Lorraine -

Artinfo August 4, 2010 Top Ten Shows to See in New York

ArtInfo August 4, 2010 Top Ten Shows to See in New York "Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913-1917" at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, through January 24, moma.org During this tumultuous period, when the artist's friends — including André Derain and the poet Apollinaire — were fighting on the front lines of the first World War, Matisse was working in the south of France on what would become the hardened core of his later oeuvre. These decisive paintings and sculpture, gathered together by a partnership between MoMA and the Art Institute of Chicago, show the artist at his most raw and experimental, stepping into new aesthetic territory not even he could define. "Christian Marclay: Festival" at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 945 Madison Avenue, through September 26, whitney.org The master of turntablism and author of creative musical notation (such as the 60- foot, 2010 "Manga Scroll" on which Marclay composed a score of booms and bangs and other noises culled from the pages of Manga comic books) is presenting work in almost every conceivable medium for this exhibition. Audiences, moreover, can enjoy an evolving lineup of concerts, and a continually changing chalkboard musical score, to which anyone can add — performances of which will be staged during the show’s run. For a museum experience, it will be noisy, but it will also offer a refreshing change from hearing only one’s quickening heartbeat in the presence of compelling art. "Picasso in the Metropolitan Museum of Art," at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, through August 15, metmuseum.org Gathering together all 300 of the museum's works by Picasso, this eye-ravishing exhibition spans the great Modern artist's career, from his early drawings and paintings — including one long-secret erotic 1903 self-portrait showing the painter being, ahem, serviced by a compliant brunette — to his experiments with linoleum cuts and his libidinous late prints. -

ROBIN RHODE Born in 1976 in Cape Town, South Africa

ROBIN RHODE Born in 1976 in Cape Town, South Africa. Lives and works in Berlin, Germany. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS (P) Performance 2019 Robin Rhode, kamel mennour, Paris 8, France 2018 Robin Rhode, Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich, Switzerland 2017 Under the Sun, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israël “Force of Circumstance”, kamel mennour, Paris, France “PATHS AND FIELDS”, Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa 2016 “PRIMITIVES”, Tucci Russo Studio Per L’Arte Contemporanea, Turin, Italy “Robin Rhode: The Moon is Asleep. SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, USA (P) 2015 “Arnold Schönberg’s Erwartung - A Performance by Robin Rhode”, Times Square, NYC, USA (P) “Robin Rhode”, North Carolina Museum of Art, USA “Drawing Waves”, The Drawing Center, NYC, NY, USA (P) “Borne Frieze”, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY, USA (P) “Recycled Matter”, Stevenson Gallery, Johannesburg, SA (P) “The Sudden Walk”, Kulturhuset / Stadsteatern Stockholm, Sweden (P) 2014 “Anima”, Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel “having been there”, Lehmann Maupin, Hong Kong “TENSION”, Tucci Russo Studio Per L’Arte Contemporanea, Turin, Italy “Robin Rhode: Animating the Everyday”, Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York, Purchase, USA “Robin Rhode: RHODE WORKS”, Kunstmuseum Luzern, Lucerne, Switzerland 2013 “The Call of Walls”, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia (P) “Paries Pictus”, Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa (P) “Take Your Mind Off The Street/Paries Pictus”, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY, USA (P) 2012 “Imaginary Exhibition”, -

2014 Exhibition Calendar Current As of December 2013

2014 Exhibition Calendar Current as of December 2013. Information is subject to change. For a listing of exhibitions and installations, please visit www.lacma.org Calder and Abstraction: From Fútbol: The Beautiful Game Treasures from Korea: Arts and Culture of Joseon Avant-Garde to Iconic Korea, 1392-1910 UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS Kaz Oshiro: Chasing Ghosts At Charles White Elementary School Gallery January 24–June 6, 2014 As part of the museum’s ongoing engagement with the community, LACMA presents Kaz Oshiro: Chasing Ghosts. Installed at LACMA’s satellite gallery within Charles White Elementary School, the exhibition juxtaposes objects Oshiro selected from the museum's collection, new work based on his interactions at the school, and student art. Oshiro is best known for creating high fidelity sculptures of everyday objects—such as microwaves, dumpsters, and file cabinets. By using the materials of painting (paint, canvas, stretcher bars) to fabricate sculpture, Oshiro’s work transcends tromp l'oeil trickery and blurs the very distinctions between the two media. Oshiro was born in Okinawa, Japan and is based in Los Angeles. Location: Charles White Elementary School is located at 2401 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90057 Curator: Sarah Jesse, Education, LACMA; Nancy Meyer, Contemporary Art, LACMA Credit: This exhibition was organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. This exhibition is made possible through the Anna H. Bing Children's Art Education Fund. Education programs at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art are supported in part by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment Fund for Arts Education, the Margaret A. Cargill Arts Education Endowment, and Rx for Reading. -

Prix-Pictet-PDF.Pdf

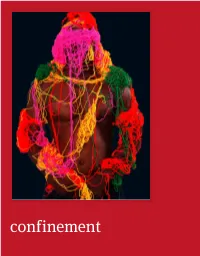

confinement confinement d Contents 2 Foreword – Renaud de Planta 4 Preface – Stephen Barber and Michael Benson 6 Essay – Peter Frankopan 10 Essay – Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi 13–100 Photographs 14 Ross McDonnell 58 Margaret Courtney-Clarke 16 Ilit Azoulay 60 Chris Steele-Perkins 18 Saskia Groneberg 62 Nadav Kander 20 Philippe Chancel 64 Nyaba Léon Ouedraogo 22 Shahidul Alam 66 Edgar Martins 24 Gideon Mendel 68 An-My Lê 26 Ori Gersht 70 Maxim Dondyuk 28 Reza Deghati 72 Susan Derges 30 Ed Kashi 74 Joana Choumali 32 Chris Jordan 76 Janelle Lynch 34 Naoya Hatakeyama 78 Edmund Clark 36 Stéphane Couturier 80 Mandy Barker 38 Matthew Brandt 82 Awoiska van der Molen 40 Robin Rhode 84 Mary Mattingly 42 Sohei Nishino 86 Edward Burtynsky 44 Rena Effendi 88 Abbas Kowsari 46 Joel Sternfeld 90 Alexia Webster 48 Benoit Aquin 92 Richard Mosse 50 Laurie Simmons 94 Valérie Belin 52 Brent Stirton 96 Pavel Wolberg 54 Motoyuki Daifu 98 Rinko Kawauchi 56 Munem Wasif 101–106 Artist Statements 107 Prix Pictet 108 Advisory Board 109 The Jury Process 110 Acknowledgments Foreword the purpose of the Prix Pictet, to quote Gro Harlem Brundtland at its launch in 2008, is ‘to ensure that matters of sustainability remain at the forefront of global debate, where they need to belong’. In the twelve years since, the two greatest threats to life on the planet – excess resource depletion and damaging climate change – have only intensified. The Prix Pictet has documented the growing sustainability crisis in images raw and beautiful from across the world. In doing so it has become one of a handful of leading global prizes for any type or genre of photography. -

Read a Free Sample

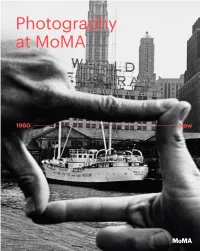

himself at a remove from the experimental practices and Thomas Florschuetz, in 1989, as well as the of various photographers as well as from the artistic exhibition British Photography from the Thatcher Photography avant-gardes of the times. Among the rare exceptions Years, in 1991. were A European Experiment, in 1967, featuring the In the Department of Photography, Szarkowski’s (sometimes abstract) work of three French and Belgian vision was complemented during his tenure by other at MoMA photographers (Denis Brihat, Pierre Cordier, and curatorial voices that sometimes ventured far from it. Jean-Pierre Sudre), and, the same year, the Surrealist The most distinctive was that of Peter C. Bunnell, photomontages of Jerry Uelsmann. In 1978 he organized a curator from 1966 to 1972, whose two principal Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960 exhibitions, Photography and Printmaking, in 1968, and around the poles of photography as a window on the Photography into Sculpture, in 1970 (fi g. 3), refl ected an world, the pure and documentary vision of the medium idea about photography that was open to other artistic Edited by that was dear to him (with work by Arbus, Friedlander, disciplines such as printmaking and sculpture. Stephen Shore, Winogrand, and others); and photography Exhibitions from outside the departmental orbit in the Quentin Bajac as a mirror or a more introspective and narrative concept 1970s revealed other photographic sensibilities: Lucy Gallun (with work by Robert Heinecken, Robert Rauschenberg, Information, organized by Kynaston McShine in 1970, Roxana Marcoci and Uelsmann). included conceptual works with a strong photographic Sarah Hermanson Meister Szarkowski’s American tropism, however, should presence, by Bernd and Hilla Becher, Victor Burgin, be placed in the broader context of MoMA’s general Douglas Huebler, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Long, and acquisition policy from the early 1960s: the institution, Robert Smithson. -

ABSTRAKT Markus Amm, Gregor Hildebrandt, Wyatt Kahn, Gerold Miller, Katy Moran, Mary Ramsden, David Renggli, Robin Rhode, Jan-Ole Schiemann

ABSTRAKT Markus Amm, Gregor Hildebrandt, Wyatt Kahn, Gerold Miller, Katy Moran, Mary Ramsden, David Renggli, Robin Rhode, Jan-Ole Schiemann Exhibition: 28 April – 15 May 2021 Wentrup is pleased to present the group exhibition ABSTRAKT during Berlin’s Gallery Weekend. The group exhibition ABSTRAKT is featuring nine artists, whose works offer different approaches to abstraction. The formal qualities of abstract artworks are significant not in themselves but as part of the work’s expressive message. Artists work by reviving and transforming archetypes from the unconscious of modern culture. Therefore, the most useful questions to ask about contemporary abstraction are: What themes and forms does it retrieve from the tradition of modern art and how have they been changed? The exhibition is combining artists that reflect different styles, materialities and visual vocabulary of abstraction. Since the late 1990s, Markus Amm has been methodically and sensitively exploring how the materials of painting, reduced to their essences, cohere into abstract images. His work can be luminous and illusionistic or bracingly sculptural and physical, and in many cases, it is both of these things simultaneously. Amm is also interested in how the perception of time informs the processes of making art and looking at it, as the processes he uses to produce many of his works require long periods of waiting and looking. The paintings therefore pose questions about how we distinguish between action and reflection. Gregor Hildebrandt’s work makes formal reference to Minimalism while engaging primarily with concepts of cross-media transfers of music and poetry into visual art. Hildebrandt’s core materials are almost exclusively sound recording media, such as magnetic audio tapes and vinyl records, which he processes, or records he records with specific songs before using them on canvas, in photographic prints, or in expansive installations.