Main Street: When a Highway Runs Through It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Power of Small State of Main Is Published As a Membership Benefi T of Main Street America, a Program of the National Main Street Center

A PUBLICATION OF MAIN STREET AMERICA WINTER 2018 The Power of Small State of Main is published as a membership benefi t of Main Street America, a program of the National Main Street Center. For information on how to join Main Street America, please visit mainstreet.org/main-street/join/. National Main Street Center, Inc. Patrice Frey President and CEO Board of Directors: Editorial Staff: Social Media: Ed McMahon, Chair Rachel Bowdon TWITTER: @NatlMainStreet Darryl Young, Vice Chair Editor in Chief Senior Manager of Content David J. Brown Development FACEBOOK: Kevin Daniels @NationalMainStreetCenter Emily Wallrath Schmidt Samuel B. Dixon Editor Joe Grills Associate Manager of INSTAGRAM: @NatlMainStreet Irvin M. Henderson Communications Laura Krizov Hannah White Contact: Mary Thompson Editor Tel.: 312.610.5611 Director of Outreach and Engagement Email: [email protected] Design: Website: mainstreet.org The Nimble Bee Main Street America has been helping revitalize older and historic commercial districts for more than 35 years. Today it is a network of more than 1,600 neighborhoods and communi- ties, rural and urban, who share both a commitment to place and to building stronger communities through preservation-based economic development. Main Street Ameri- ca is a program of the nonprofi t National Main Street Center, a subsidiary of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. © 2018 National Main Street Center, All Rights Reserved WINTER Table of contents 2018 3 President’s Note By Patrice Frey 5 Editor’s Note By Rachel Bowdon -

Articulating the Power of the Main Street and Special Assessment District Collaboration

Articulating the Power of the Main Street and Special Assessment District Collaboration Sydney Prusak University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Urban and Regional Planning & University of Wisconsin–Extension Local Government Center Spring 2017 2 Acknowledgments This work would be not possible without the support and guidance from Dr. Chuck Law, UW- Extension’s Local Government Center Director. Additional acknowledgments go to my resourceful advisor Professor Brian Ohm and supportive committee member Dr. Yunji Kim. Executive Summary Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) are an increasingly popular economic development and revitalization tool for downtown communities. This special assessment creates a unique public private partnership to support municipal improvements ranging from streetscape beautification to annual community events and festivals. This report examines the relationship of these districts with the Main Street America, in terms of funding and leadership dynamics. While the relationship between the two entities can often be contentious, this report determines the characteristics that are needed for both downtown groups to thrive. Through series of interviews with BID managers and key economic development leaders in Wisconsin, solutions and key findings for a successful downtown relationship are realized. These include organizational formation, one Board of Directors to govern both groups, continued stakeholder involvement and communication, and a dedicated envisioning process. With these practices in place, BIDs are a reliable funding source for Main Street Programs. This revitalization partnership gives property owners a direct stake in economic development planning and programming for their community. This report is meant to serve as an informational document for Main Street communities looking to create a BID as well as for BIDs interested in the Main Street Program. -

Oklahoma Main Street

Oklahoma Main Street Program Guide and Handbook Restore, Restructure, Revitalize, Results OMSC Program Guide and Handbook 1 Welcome Welcome to the Oklahoma Main Street network! You are now part of a group of dedicated and knowledgeable Main Street directors, volunteers and board members statewide, who have also decided to take on the challenge of working to revitalize their communities’ commercial historic districts. The Main Street Approach is part of a national movement whose primary focus is creating a positive economic impact. The Oklahoma Main Street Program, established in 1985, is overseen by the Oklahoma Department of Commerce. Main Street work can be both rewarding and challenging. Keeping that in mind, we have designed this resource guide to provide you with an introduction to your new responsibilities – whether as board member, volunteer or paid director. I, along with the Buffy Hughes rest of the Oklahoma Main Street Center staff, am dedicated State Main Street Director to helping your program grow while you help your downtown become a positive catalyst for change. I encourage you to take this opportunity to learn as much as you can about your downtown and the Main Street Approach. Again, welcome! We look forward to assisting you with the revitalization of your downtown. Sincerely, 2 Contents NATIONAL MAIN STREET PROGRAM History of the Main Street Program.....................................4 The Four Point Approach......................................................6 Eight Guiding Principles.......................................................8 -

Rose Cottage, Main Street, Melbourne, YO42

Rose Cottage, Main Street, Melbourne, YO42 4QJ • BEAUTIFULLY PRESENTED COTTAGE DATING BACK TO LATE 1700's • LIVING ROOM • DINING ROOM • GARDEN ROOM WITH Location EXPOSED WELL • DINING KITCHEN, UTILITY AND DOWNSTAIRS WC • FOUR DOUBLE BEDROOMS AND ONE LARGE SINGLE • MASTER WITH ENSUITE BATHROOM & FAMILY BATHROOM WITH SEPARATE SHOWER • OIL CENTRAL HEATING AND uPVC Melbourne has a thriving community spirit and holds DOUBLE GLAZING • DOUBLE GARAGE PLUS DOUBLE CAR PORT WITH PLENTY OF ADDITIONAL PARKING • MAGICAL GARDEN many activities within the village hall and chapel. It is WITH POND AND SEATING AREAS • EPC RATING = D • situated approx. 5 miles south west of Pocklington and approx. 9 miles south east of York. Within the village are an infant & primary school, local village shop and public Asking Price £485,000 house. There is also an outreach Post Office that visits. Recreational facilities ae located on the edge of the This delightful yet spacious cottage dating back to the late 1700’s is full of surprises. Having been upgraded to a high village. Pocklington Canal has SSSI status. The canal standard by the current owners, the size of the accommodation is not what you would expect in a cottage of this age. basin provides boat trips and is a lovely area for families The hidden gem of this property is the garden to the rear that is full of the ‘wow’ factor. to walk and enjoy the countryside. Melbourne is ideally To the front is the entrance hall, with boot room, and then leads into the good sized living room with log burner and placed to enjoy village life, yet be within easy reach of feature brick wall. -

Extending Main Street's Reach: an Evaluation of Pennsylvania's Elm Street Program

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2021 Extending Main Street's Reach: An Evaluation of Pennsylvania's Elm Street Program Hanna Stark Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Stark, Hanna, "Extending Main Street's Reach: An Evaluation of Pennsylvania's Elm Street Program" (2021). Theses (Historic Preservation). 721. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/721 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/721 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Extending Main Street's Reach: An Evaluation of Pennsylvania's Elm Street Program Abstract Many residential neighborhoods of Pennsylvania's older cities and towns have seen disinvestment and outmigration, which prompted Representative Robert Freeman to develop the Elm Street program. This program recognizes the interdependence of healthy residential neighborhoods and robust downtown commercial districts and shares the Main Street Four-Points Approach's principle of comprehensive, community-based strategies for revitalization. Presently, there is one designation Elm Street community with seven other "practicing" organizations that were formerly designated. This study fills a literature gap on the Elm Street program by detailing its development while evaluating Elm Street organizations' characteristics to provide recommendations to broaden and enrich the program's utilization. Interviews were held with many involved in the program's creation to understand how the program has evolved since enactment. Elm Street managers who implement the program were also interviewed. It was apparent that specific characteristics contributed to organizations' sustainability, such as mission, organizational partnerships, funding sources, size: area and population, CLG status, and redesignation. -

US 69/75 Upgrade to Limited Access Highway

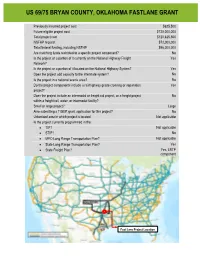

US 69/75 BRYAN COUNTY, OKLAHOMA FASTLANE GRANT Previously incurred project cost $625,500 Future eligible project cost $120,000,000 Total project cost $120,625,500 NSFHP request $72,000,000 Total federal funding, including NSFHP $96,000,000 Are matching funds restricted to a specific project component? No Is the project or a portion of it currently on the National Highway Freight Yes Network? Is the project or a portion of it located on the National Highway System? Yes Does the project add capacity to the Interstate system? No Is the project in a national scenic area? No Do the project components include a rail/highway grade crossing or separation Yes project? Does the project include an intermodal or freight rail project, or a freight project No within a freight rail, water, or intermodal facility? Small or large project? Large Also submitting a TIGER grant application for this project? No Urbanized area in which project is located Not applicable Is the project currently programmed in the: TIP? Not applicable STIP? No MPO Long Range Transportation Plan? Not applicable State Long Range Transportation Plan? Yes State Freight Plan? Yes, LRTP component Fast Lane Project Location Fast Lane Project Location 1 US 69/75 BRYAN COUNTY, OKLAHOMA FASTLANE GRANT PROJECT NARRATIVE TABLE OF CONTENTS PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 PROJECT LOCATION ............................................................................................................................................... -

2021 LIMITED ACCESS STATE NUMBERED HIGHWAYS As of December 31, 2020

2021 LIMITED ACCESS STATE NUMBERED HIGHWAYS As of December 31, 2020 CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF Transportation BUREAU OF POLICY AND PLANNING Office of Roadway Information Systems Roadway INVENTORY SECTION INTRODUCTION Each year, the Roadway Inventory Section within the Office of Roadway Information Systems produces this document entitled "Limited Access - State Numbered Highways," which lists all the limited access state highways in Connecticut. Limited access highways are defined as those that the Commissioner, with the advice and consent of the Governor and the Attorney General, designates as limited access highways to allow access only at highway intersections or designated points. This is provided by Section 13b-27 of the Connecticut General Statutes. This document is distributed within the Department of Transportation and the Division Office of the Federal Highway Administration for information and use. The primary purpose to produce this document is to provide a certified copy to the Office of the State Traffic Administration (OSTA). The OSTA utilizes this annual listing to comply with Section 14-298 of the Connecticut General Statutes. This statute, among other directives, requires the OSTA to publish annually a list of limited access highways. In compliance with this statute, each year the OSTA publishes the listing on the Department of Transportation’s website (http://www.ct.gov/dot/osta). The following is a complete listing of all state numbered limited access highways in Connecticut and includes copies of Connecticut General Statute Section 13b-27 (Limited Access Highways) and Section 14-298 (Office of the State Traffic Administration). It should be noted that only those highways having a State Route Number, State Road Number, Interstate Route Number or United States Route Number are listed. -

Downtown Traffic and Circulation Study

Downtown Traffic and Circulation Study Orono, Maine by Sebago Technics, Inc. August, 2017 Downtown Traffic and Circulation Study 1 Executive Summary This Executive Summary is intended to provide the reader with a quick synopsis of the scope, findings, and resulting recommendations of this Study. It does not provide all of the specific details that went into the development of the final conclusions, which resulted from a thorough vetting process with Town staff. For this information we direct your attention to the full body of the Report. The Town of Orono engaged Sebago Technics (Sebago) in late 2014 to conduct a comprehensive traffic and circulation study of their downtown with the primary objectives being twofold: . To enhance the safe and efficient movement of all travel modes within the downtown, including vehicles, walkers, bicyclists, and transit users. To create safe connections for all interests within the downtown TIF District. This evaluation has four main elements, each of which will be discussed separately herein: 1. Main Street – Westwood Drive to the Bridge 2. School Campus Circulation and Municipal Complex Access 3. The Alley between Mill Street and the Public Parking Lot off Pine Street 4. Longer-Term Considerations, Including Future Roadway Connectivity west of Main Street and Satellite Park-and-Ride Lots The findings presented herein for each of the four main focus areas represent the results of a combination of new data collection by Sebago and BACTS; historical information from MaineDOT, BACTS, and the local transit providers (the Community Connector and the Black Bear Express); and input from interviews with Town staff and the local school administration. -

Access Control

Access Control Appendix D US 54 /400 Study Area Proposed Access Management Code City of Andover, KS D1 Table of Contents Section 1: Purpose D3 Section 2: Applicability D4 Section 3: Conformance with Plans, Regulations, and Statutes D5 Section 4: Conflicts and Revisions D5 Section 5: Functional Classification for Access Management D5 Section 6: Access Control Recommendations D8 Section 7: Medians D12 Section 8: Street and Connection Spacing Requirements D13 Section 9: Auxiliary Lanes D14 Section 10: Land Development Access Guidelines D16 Section 11: Circulation and Unified Access D17 Section 12: Driveway Connection Geometry D18 Section 13: Outparcels and Shopping Center Access D22 Section 14: Redevelopment Application D23 Section 15: Traffic Impact Study Requirements D23 Section 16: Review / Exceptions Process D29 Section 17: Glossary D31 D2 Section 1: Purpose The Transportation Research Board Access Management Manual 2003 defines access management as “the systematic control of the location, spacing, design, and operations of driveways, median opening, interchanges, and street connections to a roadway.” Along the US 54/US-400 Corridor, access management techniques are recommended to plan for appropriate access located along future roadways and undeveloped areas. When properly executed, good access management techniques help preserve transportation systems by reducing the number of access points in developed or undeveloped areas while still providing “reasonable access”. Common access related issues which could degrade the street system are: • Driveways or side streets in close proximity to major intersections • Driveways or side streets spaced too close together • Lack of left-turn lanes to store turning vehicles • Deceleration of turning traffic in through lanes • Traffic signals too close together Why Access Management Is Important Access management balances traffic safety and efficiency with reasonable property access. -

High Occupancy Vehicle Lanes Evaluation Ii

HIGH OCCUPANCY VEHICLE LANES EVALUATION II Traffic Impact, Safety Assessment, and Public Acceptance Dr. Peter T. Martin, Associate Professor University of Utah Dhruvajyoti Lahon, Aleksandar Stevanovic, Research Assistants University of Ut ah Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering University of Utah Traffic Lab 122 South Central Campus Drive Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 November 2004 Acknowledgements The authors thank the Utah Department of Transportation employees for the data they furnished and their assistance with this study. The authors particularly thank the Technical Advisory Committee members for their invaluable input throughout the study. The authors are also thankful to the respondents who took the time to participate in the public opinion survey. The valuable contribution of those who helped collect data and conduct public opinion surveys is greatly appreciated. Disclaimer The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation, University Transportation Centers Program, in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................1 1.1 Background................................................................................................................1 -

Downtowns Matter

36 StAte of mAin FALL 2016 Downtowns matter Travel teaches you many things, not the least of which is that downtowns matter. Downtowns are the heart and soul of our communities. They are also an indicator of larger social and economic trends. For many years, the decline of America’s downtowns was an indicator of a larger trend of people and jobs leaving cities for our far flung suburbs. Now, our down- towns are coming back to life and they are a harbinger of larger social, economic, demographic and technological trends. Photo: Ed McMahon DOWNTOWNS MATTER 37 By Edward T. McMahon Edward T. sensitive develop- periodicals. He Downtowns matter There are over 25,000 incorporated commu- McMahon is the ment policies and serves on several Chairman of the nities in America. Many are prospering, but practices. He is also advisory boards NMSC Board of a senior staff and commissions many others are not. How is it that some Directors. He also adviser for ULI’s including the small cities and towns can prosper, while holds the Charles Building Healthy Chesapeake many others are suffering disinvestment, loss Fraser Chair on Places Initiative, Conservancy, the of identity and even abandonment? Sustainable and is a sought- Governors Institute Why are some communities able to maintain their Development and after speaker and for Community historic character and quality of life in the face of a is a Senior Resident thinker on land use Design and the rapidly changing world, while others have lost the Fellow at the Urban and economic Orton Family very features that once gave them distinction and Land Institute in development Foundation. -

Additional Agenda Item Attachment

ATTACHMENT A A RESOLUTION RELATING TO THE WEST MAIN STREET ROAD DIET AND PAVEMENT MARKING STUDY AND OAK-POPLAR NEIGHBORHOOD TRAFFIC CIRCULATION STUDY Draft Resolution No.114/2011-12 WHEREAS, Carrboro Vision 2020 states that the “safe and adequate flow of bus, auto, bicycle and pedestrian traffic within and around Carrboro is essential”; and, WHEREAS, the Carrboro Downtown Traffic Circulation Study (2005) and Carrboro Comprehensive Bicycle Transportation Plan (2009) recommend road diet concepts for the four-lane section of West Main Street; and, WHEREAS, on February 8, 2011, the Board of Aldermen adopted a resolution directing Town staff to draft a letter to NCDOT conveying interest in the road diet concept and directing that an associated traffic and safety analysis be completed; and, WHEREAS, on September 16, 2008, the Board of Aldermen adopted a resolution directing staff to organize a neighborhood meeting to discuss traffic management in the Oak-Poplar neighborhood, bounded by N. Greensboro St., W. Main St., Weaver St., and Carrboro Elementary; and, WHEREAS, through the Durham-Chapel Hill-Carrboro Metropolitan Planning Organization, the consulting firm Martin/Alexiou/Bryson was procured to conduct the road diet analysis and neighborhood traffic study; and, WHEREAS, a report including both studies was subsequently prepared and received by the Board of Aldermen on March 6, 2012; NOW, THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED by the Carrboro Board of Aldermen that: 1. The Board of Aldermen accepts the West Main Street Road Diet and Pavement Marking Study and the Oak-Poplar Neighborhood Traffic Circulation Study. 2. The Board of Aldermen provides the following comments and direction on the studies: a.