A Report on the 2009 Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glaadawards March 16, 2013 New York New York Marriott Marquis

#glaadawards MARCH 16, 2013 NEW YORK NEW YORK MARRIOTT MARQUIS APRIL 20, 2013 LOS AnGELES JW MARRIOTT LOS AnGELES MAY 11, 2013 SAN FRANCISCO HILTON SAN FRANCISCO - UnION SQUARE CONNECT WITH US CORPORATE PARTNERS PRESIDENT’S LETTer NOMINEE SELECTION PROCESS speCIAL HONOrees NOMINees SUPPORT FROM THE PRESIDENT Welcome to the 24th Annual GLAAD Media Awards. Thank you for joining us to celebrate fair, accurate and inclusive representations of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community in the media. Tonight, as we recognize outstanding achievements and bold visions, we also take pause to remember the impact of our most powerful tool: our voice. The past year in news, entertainment and online media reminds us that our stories are what continue to drive equality forward. When four states brought marriage equality to the election FROM THE PRESIDENT ballot last year, GLAAD stepped forward to help couples across the nation to share messages of love and commitment that lit the way for landmark victories in Maine, Maryland, Minnesota and Washington. Now, the U.S. Supreme Court will weigh in on whether same- sex couples should receive the same federal protections as straight married couples, and GLAAD is leading the media narrative and reshaping the way Americans view marriage equality. Because of GLAAD’s work, the Boy Scouts of America is closer than ever before to ending its discriminatory ban on gay scouts and leaders. GLAAD is empowering people like Jennifer Tyrrell – an Ohio mom who was ousted as leader of her son’s Cub Scouts pack – to share their stories with top-tier national news outlets, helping Americans understand the harm this ban inflicts on gay youth and families. -

Supplement to the City Record the Council —Stated Meeting of Thursday, March 25, 2010

SUPPLEMENT TO THE CITY RECORD THE COUNCIL —STATED MEETING OF THURSDAY, MARCH 25, 2010 The Invocation was delivered by Rev. Princess Thorbs, Assisting Minister, New THE COUNCIL Jerusalem Baptist Church, 122-05 Smith Street, Jamaica, New York, 11433. Minutes of the Let us pray. STATED MEETING Gracious God, God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, of We thank You, God, for another day. Thursday, March 25, 2010, 2:50 p.m. Now Lord, we ask that You would enter into this chamber. We welcome you, Father The President Pro Tempore (Council Member Rivera) that you would allow Your anointing Acting Presiding Officer and Your wisdom to be upon Your people. God bless those with Your wisdom Council Members that are going to be ruling over Your people. Give them your divine guidance according to Your will. Christine C. Quinn, Speaker Amen. Maria del Carmen Arroyo Vincent J. Gentile James S. Oddo Charles Barron Daniel J. Halloran III Annabel Palma Council Member Comrie moved to spread the Invocation in full upon the Record. Gale A. Brewer Vincent M. Ignizio Domenic M. Recchia, Jr. Fernando Cabrera Robert Jackson Joel Rivera Margaret S. Chin Letitia James Ydanis A. Rodriguez At a later point in the Meeting, the Speaker (Council Member Quinn) Leroy G. Comrie, Jr. Peter A. Koo Deborah L. Rose acknowledged the presence of former Council Member David Yassky and Council Member-elect David Greenfield (44th Council District, Brooklyn) in the Chambers. Elizabeth S. Crowley G. Oliver Koppell James Sanders, Jr. Inez E. Dickens Karen Koslowitz Larry B. Seabrook ADOPTION OF MINUTES Erik Martin Dilan Bradford S. -

Feb 11, 2018 Inauguration of NYS Senator Brian Patrick Kavanagh Hon Gale a Brewer, Manhattan Borough President Good Afternoon

Feb 11, 2018 Inauguration of NYS Senator Brian Patrick Kavanagh Hon Gale A Brewer, Manhattan Borough President Good afternoon. I’m Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, and it’s my honor and pleasure to say a few things about my colleague, confidante, and very close friend, Senator Brian Kavanagh. We go back 18 years now. It was 2001, and I’d gotten started late on my first City Council campaign. There were already six candidates in the race. We had no money. A lot of people had already taken sides, and it seemed like a long shot. Jessica Mates– another close friend and my chief of staff today – and Brian Kavanagh were there with me every day, building the campaign, stuffing 20 story buildings in the summer heat, handing out lit, keeping calm, and out–working out– thinking, and out-strategizing everybody. That, you may remember, was a Mayoral year when another candidate was running, too, a long shot we’d never heard of, a guy named Mike Bloomberg. Well, we both won, and Brian became my first chief of staff. I’d promised to “hit the ground running,” and we did thanks to Brian’s smarts and hard work, gift for organizing a staff, setting clear priorities, and managing everything in that calm, confident, steady way that is his trademark. 1 He even headed up the Fresh Democracy Project, which was a grouping of the large class of incoming Council Members in January 2002. We produced policy ideas for the new Council, but the “we” was really Brian. And he surprised us, too, with special gifts. -

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017 NEW YORK LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS nylcv.org/nycscorecard INTRODUCTION Each year, the New York League of Conservation Voters improve energy efficiency, and to better prepare the lays out a policy agenda for New York City, with goals city for severe weather. we expect the Mayor and NYC Council to accomplish over the course of the proceeding year. Our primary Last month, Corey Johnson was selected by his tool for holding council members accountable for colleagues as her successor. Over the years he has progress on these goals year after year is our annual been an effective advocate in the fight against climate New York City Council Environmental Scorecard. change and in protecting the health of our most vulnerable. In particular, we appreciate his efforts In consultation with over forty respected as the lead sponsor on legislation to require the environmental, public health, transportation, parks, Department of Mental Health and Hygiene to conduct and environmental justice organizations, we released an annual community air quality survey, an important a list of eleven bills that would be scored in early tool in identifying the sources of air pollution -- such December. A handful of our selections reward council as building emissions or truck traffic -- particularly members for positive votes on the most significant in environmental justice communities. Based on this environmental legislation of the previous year. record and after he earned a perfect 100 on our City The remainder of the scored bills require council Council Scorecard in each year of his first term, NYLCV members to take a public position on a number of our was proud to endorse him for re-election last year. -

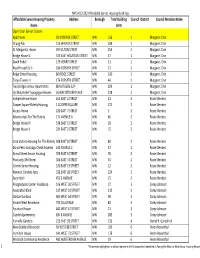

Master 202 Property Profile with Council Member District Final For

NYC HUD 202 Affordable Senior Housing Buildings Affordable Senior Housing Property Address Borough Total Building Council District Council Member Name Name Units Open Door Senior Citizens Apartment 50 NORFOLK STREET MN 156 1 Margaret Chin Chung Pak 125 WALKER STREET MN 104 1 Margaret Chin St. Margarets House 49 FULTON STREET MN 254 1 Margaret Chin Bridge House VI 323 EAST HOUSTON STREET MN 17 1 Margaret Chin David Podell 179 HENRY STREET MN 51 1 Margaret Chin Nysd Forsyth St Ii 184 FORSYTH STREET MN 21 1 Margaret Chin Ridge Street Housing 80 RIDGE STREET MN 100 1 Margaret Chin Tanya Towers II 174 FORSYTH STREET MN 40 1 Margaret Chin Two Bridges Senior Apartments 80 RUTGERS SLIP MN 109 1 Margaret Chin Ujc Bialystoker Synagogue Houses 16 BIALYSTOKER PLACE MN 128 1 Margaret Chin Independence House 165 EAST 2 STREET MN 21 2 Rosie Mendez Cooper Square Elderly Housing 1 COOPER SQUARE MN 151 2 Rosie Mendez Access House 220 EAST 7 STREET MN 5 2 Rosie Mendez Alliance Apts For The Elderly 174 AVENUE A MN 46 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House IV 538 EAST 6 STREET MN 18 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House V 234 EAST 2 STREET MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Casa Victoria Housing For The Elderly 308 EAST 8 STREET MN 80 2 Rosie Mendez Dona Petra Santiago Check Address 143 AVENUE C MN 57 2 Rosie Mendez Grand Street Senior Housing 709 EAST 6 STREET MN 78 2 Rosie Mendez Positively 3Rd Street 306 EAST 3 STREET MN 53 2 Rosie Mendez Cabrini Senior Housing 220 EAST 19 STREET MN 12 2 Rosie Mendez Renwick Gardens Apts 332 EAST 28 STREET MN 224 2 Rosie Mendez Securitad I 451 3 AVENUE MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Postgraduate Center Residence 516 WEST 50 STREET MN 22 3 Corey Johnson Associated Blind 137 WEST 23 STREET MN 210 3 Corey Johnson Clinton Gardens 404 WEST 54 STREET MN 99 3 Corey Johnson Encore West Residence 755 10 AVENUE MN 85 3 Corey Johnson Fountain House 441 WEST 47 STREET MN 21 3 Corey Johnson Capitol Apartments 834 8 AVENUE MN 285 3 Corey Johnson Yorkville Gardens 225 EAST 93 STREET MN 133 4 Daniel R. -

Elected Officials

KOSCIUSZKO BRIDGE PROJECT STAKEHOLDERS ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP LIST NAME/TITLE/ORGANIZATION REPRESENTATIVE ALTERNATE(S) Elected Officials Nydia Velazquez United States Congresswoman Evelyn Cruz Marty Markowitz Brooklyn Borough President Michael Rossmy Alvin Goodman Helen Marshall Queens Borough President Thomas Campagna Mark Scott Martin Connor New York State Senator Naftali Ausch Martin Malave Dilan New York State Senator Anna Zak Serphin Maltese New York State Senator Rosemarie Iacovone George Onorato New York State Senator Joseph Lentol New York State Assembly Member Theresa Cianciotta Vito Lopez New York State Assembly Member Alison Hirsh Margaret Markey New York State Assembly Member Welland Fuller Catherine Nolan New York State Assembly Member Diane Ballek Eric Gioia New York City Council Member Zoe Epstein Melinda Katz New York City Council Member Jay Bond Leora Skolnick Diana Reyna New York City Council Member David Yassky New York City Council Member Matt Ides NAME/TITLE/ORGANIZATION REPRESENTATIVE ALTERNATE(S) Agencies Douglas Currey Regional Director Robert Adams NYS Department of Transportation Iris Weinshall Commissioner Muhammed Afzal Mousa Nazif NYC Department of Transportation Moshe Strum Robert Arnold Division Administrator Tom Breslin Rick Backlund Federal Highway Administration Brooklyn Community Board #1 Gerald Esposito Philip Caponegro Queens Community Board #2 Debra Markell Marilyn Elseroad Gary Giordano Queens Community Board #5 Vincent Arcuri John Schell Civic and Neighborhood Organizations Apollo Street/Meeker -

Community Board No. 8 Calvary Community Church 1575 St. John's

Community Board No. 8 Calvary Community Church 1575 St. John’s Place Brooklyn, NY 11213 May 10, 2012 Members Present Members Absent Akosua Albritton Kim Albert Glinda Andrews Viloa Bing Desmond Atkins Dr. Flize Bryan LeeAnn Banks Angelina Pinto Princess Benn-James Cy Richardson Samantha Bernadine Patricia Scantlebury Julia Boyd William Suggs Gail Branch-Muhammad Deborah Young Helen Coley Renaye Cuyler Elected Officials Present James Ellis Diama Foster Councilman Al Vann, 36th Council District Ede Fox Shirley Patterson, 43rd Assembly District Leader Fred Frazier Nizjoni Granville Elected Official’s Representatives Curtis Harris Doris Heriveaux J. Markowicz, Assemblywoman Robinson’s Office XeerXeema Jordan Charles Jackson, Congresswoman Clarke’s Office Shalawn Langhorne Simone Hawkins, Councilwoman James’s Office Priscilla Maddox Jim Vogel, Senator Montgomery’s Office Robert Matthews Kwasi Mensah Liaisons Present Adelaide Miller Dr. Frederick Monderson Sophia Jones, Bklyn Boro Pres. Office Atim oton Andrea Phillips-Merriman, Brooklyn Alton Pierce Neighborhood Improvement Association Robert Puca Mary Reed CB Staff Present Marlene Saunders Stacey Sheffey Michelle George, District Manager Meredith Staton Julia Neale, Community Associate Audrey Taitt-Hall Valerie Hodges-Mitchell, Comm. Service Aide Launa Thomas-Bullock Gregory Todd Ethel Tyus Yves Vilus Sharon Wedderburn Robert Witherwax Vilma Zuniga FOREST CITY RATNER COMPANIES – Ms. Ashley Cotton BROOKLYN EVENTS CENTER – Mr. David Anderson Ms. Cotton announced that there will be 2000 jobs created by the Barclays Arena opening. FCRC has launched an outreach initiative to fill the positions, and has agreed to seek to hire residents from Community Boards 2, 3, 6, 8 and graduates of the BUILD training program, as well as NYCHA residents. -

Recchia Based on New York City Council Discretionary Funding (2009-2013)

Recchia Based on New York City Council Discretionary Funding (2009-2013) Fiscal Year Source Council Member 2012 Local Recchia Page 1 of 768 10/03/2021 Recchia Based on New York City Council Discretionary Funding (2009-2013) Legal Name EIN Status Astella Development Corporation 112458675- Cleared Page 2 of 768 10/03/2021 Recchia Based on New York City Council Discretionary Funding (2009-2013) Amount Agency Program Name 15000.00 DSBS Page 3 of 768 10/03/2021 Recchia Based on New York City Council Discretionary Funding (2009-2013) Street Address 1 Street Address 2 1618 Mermaid Ave Page 4 of 768 10/03/2021 Recchia Based on New York City Council Discretionary Funding (2009-2013) Postcode Purpose of Funds 11224 Astella Development Corp.’s “Mermaid Ave. Makeover Clean Streets Campaign†will rid Mermaid Ave. sidewalks and street corners of liter and surface dirt and stains. Astella will collaborate with the NYC Department of Sanitation, the Coney Island Board of Trade, and Mermaid Ave. merchants to provide these services. Members of the Coney Island Board of Trade, in which Astella helped to revitalize and provides technical assistance, have noted that while most merchants keep the sidewalk area in front of their stores free of liter according to city law, additional liter and sidewalk dirt and stains accumulate throughout the remainder of the day. In addition, according to a survey of Mermaid Ave. merchants conducted by an Astella intern in 2010, cleanliness of Mermaid Ave. was cited as the number one concern among merchants on Mermaid Ave. A cleaner commercial corridor will inspire confidence and pride in the neighborhood, provide a welcoming environment for shoppers, a boost for Mermaid Ave. -

SCHEDULE for MAYOR BILL DE BLASIO CITY of NEW YORK Saturday, February 01, 2014

SCHEDULE FOR MAYOR BILL DE BLASIO CITY OF NEW YORK Saturday, February 01, 2014 9:40 - 10:10 AM COMMUNICATIONS CALL Staff: Monica Klein 10:15 - 10:45 AM TOBOGGAN RUN Location: Drop off: In front of 575 7th avenue Attendees: (t)Commissioner Roger Goodell , (t)Senator Charles E. Schumer, First Lady, Dante de Blasio Press Staff: Wiley Norvell 11:00 - 11:30 AM SUPERBOWL BOULEVARD FIELD GOAL KICK Location: Superbowl Boulevard, Broadway bewtween 45th & 46th Streets Attendees: Dante de Blasio 1:50 - 3:00 PM SUPER BOWL XLVIII HANDOFF CEREMONY Location: Roman Numerals Stage Drop Off: 7th avenue b/w 42nd and 43rd street Attendees: (t) Governor Christie; (t) Governor Cuomo; Governor Brewer(Arizona); Woody Johnson, NY/NJ Super Bowl Host Committee Co-Chair & NY Jets Owner; Jonathan Tisch, NY/NJ Super Bowl Host Committee Co-Chair & NY Giants Owner ; Al Kelly, NY/NJ Super Bowl Host Committee President and CEO (Emcee); Michael Bidwill, Arizona Cardinals Owner; David Rousseau, Arizona Super Bowl Host Committee; Jay Parry, Arizona Super Bowl Host Committee CEO Press Staff: Wiley Norvell, Marti Adams 3:00 - 3:30 PM DEPART BOWL XLVIII HANDOFF CEREMONY EN ROUTE RESIDENCE Drive Time: 30 mins Car : BdB, DdB, Follow: Javon SCHEDULE FOR MAYOR BILL DE BLASIO CITY OF NEW YORK Sunday, February 02, 2014 7:00 - 7:45 AM STATEN ISLAND GROUNDHOG DAY CEREMONY Location: Staten Island Zoo 614 Broadway, Staten Island, NY Attendees: Audience: 700 people On Stage: Comptroller Scott Stringer (t); Council Member Vincent Gentile; Reginald Magwood, NYS Park Director, representing -

A Look at the History of the Legislators of Color NEW YORK STATE BLACK, PUERTO RICAN, HISPANIC and ASIAN LEGISLATIVE CAUCUS

New York State Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus 1917-2014 A Look at the History of the Legislators of Color NEW YORK STATE BLACK, PUERTO RICAN, HISPANIC AND ASIAN LEGISLATIVE CAUCUS 1917-2014 A Look At The History of The Legislature 23 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The New York State Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus would like to express a special appreciation to everyone who contributed time, materials and language to this journal. Without their assistance and commitment this would not have been possible. Nicole Jordan, Executive Director Raul Espinal, Legislative Coordinator Nicole Weir, Legislative Intern Adrienne L. Johnson, Office of Assemblywoman Annette Robinson New York Red Book The 1977 Black and Puerto Rican Caucus Journal New York State Library Schomburg Research Center for Black Culture New York State Assembly Editorial Services Amsterdam News 2 DEDICATION: Dear Friends, It is with honor that I present to you this up-to-date chronicle of men and women of color who have served in the New York State Legislature. This book reflects the challenges that resolute men and women of color have addressed and the progress that we have helped New Yorkers achieve over the decades. Since this book was first published in 1977, new legislators of color have arrived in the Senate and Assembly to continue to change the color and improve the function of New York State government. In its 48 years of existence, I am proud to note that the Caucus has grown not only in size but in its diversity. Originally a group that primarily represented the Black population of New York City, the Caucus is now composed of members from across the State representing an even more diverse people. -

Disabled Students Letter to Mayor

THE LEGISLATURE STATE OF NEW YORK ALBANY January 14, 2021 Honorable Bill de Blasio Mayor of the City of New York City Hall, New York, NY 10007 Dear Mayor de Blasio: In these diffiCult times, we applaud you and the Chancellor for starting the hard work of developing a proaCtive plan to Close the “COVID aChievement gap” experienced by many students throughout the City. We reCognize that the details of this plan are still being determined. We write today to make several recommendations for you to consider as you work to address both the achievement gap in academic, social and physical skill areas and the regression of life among the approximately 200,000 students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). Unlike other students, this population of Children may never catch up on what was lost during the days of remote learning. With regard to the effort to provide families the option of blended or remote instruction models, appropriate staffing has beCome a Challenge, partiCularly for students with IEPs. This has been detailed in the press and in testimony from parents and other stakeholders at the joint Committee hearing of the New York City Council on the reopening of sChools (10/23/20). Additionally, parent-led advocaCy Consulting group, SpeCial Support ServiCes reCently released a report that surveyed 1,100 parents whose Children require speCial education serviCes during the initial sChools reopening, OCtober 7-26. In this report, parents desCribed numerous ways in whiCh IEP serviCes were not provided or partially provided. The following issues were identified: 1. Large Classes and Less Staffing have caused Integrated Co-Teaching Service to be Delivered Poorly: 1 ● Large sizes are over the UFT ContraCtual limit: Highest reported Blended remote ICT had 80 students. -

Community Board No. 2, M Anhattan

Tobi Bergman, Chair Antony Wong, Treasurer Terri Cude, First Vice Chair Keen Berger, Secretary Susan Kent, Second Vice Chair Daniel Miller, Assistant Secretary Bob Gormley, District Manager ! COMMUNITY BOARD NO. 2, MANHATTAN 3 W ASHINGTON SQUARE V ILLAGE N EW YORK, NY 10012-1899 www.cb2manhattan.org P: 212-979-2272 F: 212-254-5102 E : [email protected] Greenwich Village v Little Italy v SoHo v NoHo v Hudson Square v Chinatown v Gansevoort Market September 28, 2016 Margaret Forgione Manhattan Borough Commissioner NYC Department of Transportation 59 Maiden Lane, 35th Floor New York, NY 10038 Dear Commissioner Forgione: At its Full Board meeting September 22, 2016, Community Board #2, adopted the following resolution: Resolution requesting a traffic study to include granite bike paths on renovated cobblestone streets. Whereas cobblestone (or Belgian Block) streets are difficult and often unsafe for cyclists to navigate in a city that is promoting bicycle use; and Whereas the uneven cobblestone streets often have large gaps with separating stones and depressions caused by use, maintenance, and weather elements that add to the peril of riding as well as walking on the stones, especially if using high heel shoes; and Whereas cobblestone streets become even more perilous when wet; and Whereas cyclists often ride on sidewalks which is dangerous and illegal to avoid the bumpy and uneven cobblestone surfaces which contributes an additional layer of safety concerns not only for cyclists but pedestrians as well; and Whereas cobblestone streets contribute to the unique, historical character that defines many Community Board 2, Manhattan (CB2) neighborhoods and need to be preserved; and Whereas other historic neighborhoods such as DUMBO have employed granite bike paths to make cycling safe in cobblestone areas without impeding on the historical character of the cobblestone street; and Whereas a successful six ft.