From Deluge to Displacement the Impact of Post-Flood Evictions and Resettlement in Chennai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Altis Sri Lakshmi Vilas - Kotturpuram, Chennai Ultimate Abode for You and Your Loving Family

https://www.propertywala.com/altis-sri-lakshmi-vilas-chennai Altis Sri Lakshmi Vilas - Kotturpuram, Chennai Ultimate abode for you and your loving family. Altis Sri Lakshmi Vilas by Altos Properties at Kotturpuram in Chennai offers residential project that host 3 bhk and 4 bhk apartment in various sizes. Project ID: J396214118 Builder: Altis Properties Location: Altis Sri Lakshmi Vilas,Chitra Nagar, Kotturpuram, Chennai (Tamil Nadu) Completion Date: Jul, 2020 Status: Started Description Altis Sri Lakshmi Vilas built in a contemporary style and comprising 11 Luxury 3 bhk and 4 bhk apartments in the size ranges in between 2300 to 4281 sqft. it is located in the most sought after residential neighborhood - Kotturpuram. The compact apartment complex comes with its own exclusive gym, lounge and rooftop barbecue area. There are number of benefits of living in Apartments with a good locality. The location of the project makes sure that the home-seekers are choosing the right Apartments for themselves. Amenities: Landscaped Garden Gymnasium Play Area Intercom Gated community Security 24Hr Backup Electricity Altis Properties is an eminent name in the real estate market of Chennai. It strives to revolutionize the way homes, offices, and social spaces are built. The company is known for building a successful range of premium and luxury homes with a commitment to on-time delivery and solid build quality. It works hard to maximize customer delight by exceeding their expectations at every level, while also striving to deliver excellent value to its stakeholders. Ecstasea at Muttukadu, Horizon at Saligramam, and Urbanville at Velachery are some of the company’s prestigious projects. -

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 1 Kanchipuram 1 Kanchipuram 1 Angambakkam 2 Ariaperumbakkam 3 Arpakkam 4 Asoor 5 Avalur 6 Ayyengarkulam 7 Damal 8 Elayanarvelur 9 Kalakattoor 10 Kalur 11 Kambarajapuram 12 Karuppadithattadai 13 Kavanthandalam 14 Keelambi 15 Kilar 16 Keelkadirpur 17 Keelperamanallur 18 Kolivakkam 19 Konerikuppam 20 Kuram 21 Magaral 22 Melkadirpur 23 Melottivakkam 24 Musaravakkam 25 Muthavedu 26 Muttavakkam 27 Narapakkam 28 Nathapettai 29 Olakkolapattu 30 Orikkai 31 Perumbakkam 32 Punjarasanthangal 33 Putheri 34 Sirukaveripakkam 35 Sirunaiperugal 36 Thammanur 37 Thenambakkam 38 Thimmasamudram 39 Thilruparuthikundram 40 Thirupukuzhi List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 41 Valathottam 42 Vippedu 43 Vishar 2 Walajabad 1 Agaram 2 Alapakkam 3 Ariyambakkam 4 Athivakkam 5 Attuputhur 6 Aymicheri 7 Ayyampettai 8 Devariyambakkam 9 Ekanampettai 10 Enadur 11 Govindavadi 12 Illuppapattu 13 Injambakkam 14 Kaliyanoor 15 Karai 16 Karur 17 Kattavakkam 18 Keelottivakkam 19 Kithiripettai 20 Kottavakkam 21 Kunnavakkam 22 Kuthirambakkam 23 Marutham 24 Muthyalpettai 25 Nathanallur 26 Nayakkenpettai 27 Nayakkenkuppam 28 Olaiyur 29 Paduneli 30 Palaiyaseevaram 31 Paranthur 32 Podavur 33 Poosivakkam 34 Pullalur 35 Puliyambakkam 36 Purisai List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 37 -

Thiruvallur District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR 2017 TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT tmt.E.sundaravalli, I.A.S., DISTRICT COLLECTOR TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TAMIL NADU 2 COLLECTORATE, TIRUVALLUR 3 tiruvallur district 4 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT - 2017 INDEX Sl. DETAILS No PAGE NO. 1 List of abbreviations present in the plan 5-6 2 Introduction 7-13 3 District Profile 14-21 4 Disaster Management Goals (2017-2030) 22-28 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability analysis with sample maps & link to 5 29-68 all vulnerable maps 6 Institutional Machanism 69-74 7 Preparedness 75-78 Prevention & Mitigation Plan (2015-2030) 8 (What Major & Minor Disaster will be addressed through mitigation 79-108 measures) Response Plan - Including Incident Response System (Covering 9 109-112 Rescue, Evacuation and Relief) 10 Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 113-124 11 Mainstreaming of Disaster Management in Developmental Plans 125-147 12 Community & other Stakeholder participation 148-156 Linkages / Co-oridnation with other agencies for Disaster 13 157-165 Management 14 Budget and Other Financial allocation - Outlays of major schemes 166-169 15 Monitoring and Evaluation 170-198 Risk Communications Strategies (Telecommunication /VHF/ Media 16 199 / CDRRP etc.,) Important contact Numbers and provision for link to detailed 17 200-267 information 18 Dos and Don’ts during all possible Hazards including Heat Wave 268-278 19 Important G.Os 279-320 20 Linkages with IDRN 321 21 Specific issues on various Vulnerable Groups have been addressed 322-324 22 Mock Drill Schedules 325-336 -

106Th MEETING

106th MEETING TAMIL NADU STATE COASTAL ZONE MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY Date: 25.07.2019 Venue: Time: 11.00 A.M Conference Hall, 2nd floor, Namakkal Kavinger Maligai, Secretariat, Chennai – 600 009 INDEX Agenda Pg. Description No. No. 01 Confirmation of the minutes of the 105th meeting of the Tamil Nadu State 1 Coastal Zone Management Authority held on 21.05.2019 02 The action taken on the decisions of 105th meeting of the Authority held on 12 21.05.2019 03 Construction of 30” OD Underground Natural Gas Pipeline of M/s. Indian Oil Corporation Ltd., from Ennore LNG Terminal situated inside Kamarajar Port Limited, Ennore, Tiruvallur district to Salavakkam Village, Uthiramerur Taluk, 15 Kancheepuram district 04 Construction of doubling of Railway Line between Existing Holding Yard No.1 at Ch.00m (Near Bridge No.5) to Entry of Container Rail Terminal Yard of M/s. Kamarajar Port Ltd., at Athipattu, Puzhuthivakkam and Ennore Village of 17 Ponneri Taluk, Tiruvallur district 05 Erection of Transmission tower and transmission line for 400 KV power evacuation line from SEZ to Ennore Thermal Power Station (ETPS) expansion project, SEZ to North Chennai (NC) Pooling Station, EPS expansion project to NC Pooling Station and 765 KV Power evacuation line from North Chennai 19 Thermal Power Station-Stage-III (NCTPS-III) to NC Pooling Station at Ennore by M/s. Tamil Nadu Transmission Corporation Limited (TANTRANSCO) 06 Revalidation of CRZ Clearance for the Foreshore facilities viz., Pipe Coal Conveyor, Cooling Water Intake and Outfall Pipeline for the project and ETPS Expansion Thermal Power Project (1x660 MW) proposed within the existing 21 ETPS at Ernavur Village, Thiruvottiyur Taluk, Tiruvallur district proposed by TANGEDCO 07 Proposed Container Transit Terminal at S.F.No.1/3B3, Pulicat Road, Kattupalli Village, Tiruvallur district by M/s. -

Telephone Numbers

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY THANJAVUR IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS DISTRICT EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTRE THANJAVUR DISTRICT YEAR-2018 2 INDEX S. No. Department Page No. 1 State Disaster Management Department, Chennai 1 2. Emergency Toll free Telephone Numbers 1 3. Indian Meteorological Research Centre 2 4. National Disaster Rescue Team, Arakonam 2 5. Aavin 2 6. Telephone Operator, District Collectorate 2 7. Office,ThanjavurRevenue Department 3 8. PWD ( Buildings and Maintenance) 5 9. Cooperative Department 5 10. Treasury Department 7 11. Police Department 10 12. Fire & Rescue Department 13 13. District Rural Development 14 14. Panchayat 17 15. Town Panchayat 18 16. Public Works Department 19 17. Highways Department 25 18. Agriculture Department 26 19. Animal Husbandry Department 28 20. Tamilnadu Civil Supplies Corporation 29 21. Education Department 29 22. Health and Medical Department 31 23. TNSTC 33 24. TNEB 34 25. Fisheries 35 26. Forest Department 38 27. TWAD 38 28. Horticulture 39 29. Statisticts 40 30. NGO’s 40 31. First Responders for Vulnerable Areas 44 1 Telephone Number Officer’s Details Office Telephone & Mobile District Disaster Management Agency - Thanjavur Flood Control Room 1077 04362- 230121 State Disaster Management Agency – Chennai - 5 Additional Cheif Secretary & Commissioner 044-28523299 9445000444 of Revenue Administration, Chennai -5 044-28414513, Disaster Management, Chennai 044-1070 Control Room 044-28414512 Emergency Toll Free Numbers Disaster Rescue, 1077 District Collector Office, Thanjavur Child Line 1098 Police 100 Fire & Rescue Department 101 Medical Helpline 104 Ambulance 108 Women’s Helpline 1091 National Highways Emergency Help 1033 Old Age People Helpline 1253 Coastal Security 1718 Blood Bank 1910 Eye Donation 1919 Railway Helpline 1512 AIDS Helpline 1097 2 Meteorological Research Centre S. -

GREENS E BROCHURE Digital

www.ozonegroup.com WELCOME TO THE TOWNSHIP OF THE FUTURE LOCATED NEXT TO ELCOT SEZ, SHOLINGANALLUR, CHENNAI Perumbakkam Perumbakkam NURTURE YOUR DREAMS FOR THE FUTURE, IN THE TOWNSHIP OF TOMORROW. Bring alive a world of endless possibilities for your family and you when you move into this integrated township. Choose a world of amenities, an active and healthy lifestyle, tech-enabled infrastructure, eco-friendly environment and more. Discover the future of living with Greens! One of Ozone Group’s latest residential projects in Chennai, Greens offers 1BHK, 2BHK, 2.5BHK, 3BHK and 4BHK apartments within an integrated township for a futuristic living experience. Perumbakkam DISCOVER A SAFE, SUSTAINABLE AND FUTURISTIC LIVING ENVIRONMENT BUILT ON THE 5 PILLARS OF INFRASTRUCTURE, AMENITIES, PRODUCT MIX, ENVIRONMENT AND CULTURE. • INFRASTRUCTURE PROPOSED SCHOOL WIDE ROADS SECURITY & SURVEILLANCE INTERNET OF THINGS • PRODUCT MIX PLOTTED PROPOSED SENIOR LIVING COMPACT HOMES RESIDENTIAL HIGH-RISE DEVELOPMENT COMMERCIAL/RETAIL • AMENITIES • ECOFRIENDLY DEVELOPMENTS • CULTURE CLUBHOUSE TERRACE/PODIUM GARDEN PARKS AND OPEN SPACES LANDSCAPED AREAS EVENTS IMAGES SHOWN ARE FOR REPRESENTATION PURPOSE ONLY Perumbakkam AMENITIES DESIGNED FOR THE NEW AGE Once at Greens, you need not look further for that much needed break. A host of modern and contemporarily designed amenities await you, such as a dynamic clubhouse with tennis, badminton, squash, basketball, billiards, state-of-the-art gym, a yoga centre, topped with a lavish swimming pool and a whole cricket pitch. Did we mention jogging tracks around the property? Yes, that too. IMAGES SHOWN ARE FOR REPRESENTATION PURPOSE ONLY Perumbakkam LOCATION MAP LET YOUR WISHES GET WINGS, IN THE TOWNSHIP OF TOMORROW. -

S.No. Shop Address 1 Anna Nagar Shanthi Colony

S.No. Shop Address Anna Nagar Shanthi Colony Aa-144, 2nd Floor, 3rd Avenue, (Next To Waves) Anna Nagar, Ch-600040. 1 Anna Nagar West No 670,Sarovar Building, School Road, Anna Nagar West, Chennai - 600101. 2 Mogappair East 4/491, Pari Salai, Mogappair East, (Near Tnsc Bank) Ch-600037 3 Mogappair West 1 Plot No.4, 1st Floor, Phase I, Nolambur,(Near Reliance Fresh) Mogappair 4 West, Ch-600037. Annanagar West Extn Plot No: R48, Door No - 157, Tvs Avenue Main Road,Anna Nagar West 5 Extension,Chennai - 600 101. Opp To Indian Overseas Bank. Red Hills 1/172a, Gnt Road, 2nd Floor, Redhills-Chennai:52. Above Lic, Next To Iyappan 6 Temple K.K.Nagar 2 No.455, R.K.Shanuganathan Road, K K Nagar, Land Mark:Near By K M 7 Hospital, Chennai - 600 078 Tiruthani No. 9, Chittoor Road, Thirutani - 631 209 8 Anna Nagar (Lounge) C Block, No. 70, Tvk Colony, Annanagar East, Chennai - 102. 9 K.K.Nagar 1 Plot No 1068, 1st Floor, Munuswami Salai, (Opp To Nilgiri Super Market) 10 K.K.Nagar West, Ch-600078. Alapakkam No. 21, 1st Floor, Srinivasa Nagar,Alapakkam Main 11 Road,Maduravoyal,Chennai 600095 Mogappair West 2 No-113, Vellalar Street, Mogappair West, Chennai -600 037. 12 Poonamalle # 35, Trunk Road, Opp To Grt Poonamalle Chennai-600056. 13 Karayanchavadi N0. 70, Trunk Road, Karayanchavadi, Poonamallee, Chennai - 56 14 Annanagar 6th Avenue 6th Avenue,Anna Nagar,Chennai 15 Chetpet Opp To Palimarhotel,73,Casamajorroad,Egmore,Ch-600008 16 Egmore Lounge 74/26,Fagunmansion,Groundfloor,Nearethirajcollege,Egmore,Chennai-600008 17 Nungambakkam W A-6, Gems Court, New.25 (Old No14), Khader Nawaz Khan Road, (Opp Wills 18 Life Style) Nungambakkam, Ch-600034. -

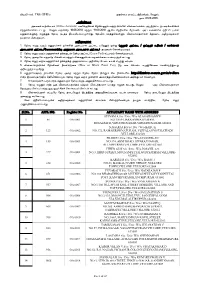

Sl.No. APPL NO. Register No. APPLICANT NAME WITH

tpLtp vz;/ 7166 -2018-v Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpkd;wk;. ntYhh;. ehs; 01/08/2018 mwptpf;if mytyf cjtpahsh; (Office Assistant) gzpfSf;fhd fPH;f;fhqk; kDjhuh;fspd; tpz;zg;g';fs; mLj;jfl;l eltof;iff;fhf Vw;Wf;bfhs;sg;gl;lJ/ nkYk; tUfpd;w 18/08/2018 kw;Wk; 19/08/2018 Mfpa njjpfspy; fPH;f;fz;l ml;ltizapy; Fwpg;gpl;Ls;s kDjhuh;fSf;F vGj;Jj; njh;t[ elj;j jpl;lkplg;gl;Ls;sJ/ njh;tpy; fye;Jbfhs;Sk; tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs; fPH;fz;l tHpKiwfis jtwhky; gpd;gw;wt[k;/ tHpKiwfs; 1/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fspd; milahs ml;il VnjDk; xd;W (Mjhu; ml;il - Xl;Leu; cupkk; - thf;fhsu; milahs ml;il-ntiytha;g;g[ mYtyf milahs ml;il) jtwhky; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 2/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSld; njh;t[ ml;il(Exam Pad) fl;lhak; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 3/ njh;t[ miwapy; ve;jtpj kpd;dpay; kw;Wk; kpd;dDtpay; rhjd’;fis gad;gLj;jf; TlhJ/ 4/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSf;F mDg;gg;gl;l mwptpg;g[ rPl;il cld; vLj;J tut[k;/ 5/ tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs;; njh;tpid ePyk;-fUik (Blue or Black Point Pen) epw ik bfhz;l vGJnfhiy gad;gLj;JkhW mwpt[Wj;jg;gLfpwJ/ 6/ kDjhuh;fSf;F j’;fspd; njh;t[ miw kw;Wk; njh;t[ neuk; ,d;Dk; rpy jpd’;fspy; http://districts.ecourts.gov.in/vellore vd;w ,izajsj;jpy; bjhptpf;fg;gLk;/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; Kd;dnu midj;J tptu’;fisa[k; mwpe;J tu ntz;Lk;/ 7/ fhyjhkjkhf tUk; ve;j kDjhuUk; njh;t[ vGj mDkjpf;fg;glkhl;lhJ/ 8/ njh;t[ vGJk; ve;j xU tpz;zg;gjhuUk; kw;wth; tpilj;jhis ghh;j;J vGjf; TlhJ. -

The Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study (CCTS)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The consultants are grateful to Tmt. Susan Mathew, I.A.S., Addl. Chief Secretary to Govt. & Vice-Chairperson, CMDA and Thiru Dayanand Kataria, I.A.S., Member - Secretary, CMDA for the valuable support and encouragement extended to the Study. Our thanks are also due to the former Vice-Chairman, Thiru T.R. Srinivasan, I.A.S., (Retd.) and former Member-Secretary Thiru Md. Nasimuddin, I.A.S. for having given an opportunity to undertake the Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study. The consultants also thank Thiru.Vikram Kapur, I.A.S. for the guidance and encouragement given in taking the Study forward. We place our record of sincere gratitude to the Project Management Unit of TNUDP-III in CMDA, comprising Thiru K. Kumar, Chief Planner, Thiru M. Sivashanmugam, Senior Planner, & Tmt. R. Meena, Assistant Planner for their unstinted and valuable contribution throughout the assignment. We thank Thiru C. Palanivelu, Member-Chief Planner for the guidance and support extended. The comments and suggestions of the World Bank on the stage reports are duly acknowledged. The consultants are thankful to the Steering Committee comprising the Secretaries to Govt., and Heads of Departments concerned with urban transport, chaired by Vice- Chairperson, CMDA and the Technical Committee chaired by the Chief Planner, CMDA and represented by Department of Highways, Southern Railways, Metropolitan Transport Corporation, Chennai Municipal Corporation, Chennai Port Trust, Chennai Traffic Police, Chennai Sub-urban Police, Commissionerate of Municipal Administration, IIT-Madras and the representatives of NGOs. The consultants place on record the support and cooperation extended by the officers and staff of CMDA and various project implementing organizations and the residents of Chennai, without whom the study would not have been successful. -

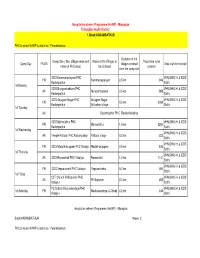

Camp Day FN/AN Camp Site ( Site, Village Name and Name of PHC Area)

Hospital on wheels Programme (HoWP) - Microplan Thiruvallur Health District 1.Block:KADAMBATHUR PHC to which HoWP is attached : Perambakkam Distance of the Camp Site ( Site, Village name and Name of the Villages to Population to be Camp Day FN/AN villages covered Area staff to involved name of PHC area) be Covered covered from the camp site ICDS Kamavarpalayam PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN Kammavarpalyam 0.5 km 946 Kadampathur Staffs 1st Monday ICDS Nungambakkam PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS AN Nungambakkam 0.5 km 988 Kadampathur Staffs ICDS Anjugam Nagar PHC Anjugam Nagar, VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN 0.5 km 2360 Kadampathur Adikathur village Staffs 1st Tuesday AN Kadambathur PHC Review Meeting ICDS Mellnalathur PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN Mellnalathur 1.0 km 3264 Kadampathur Staffs 1st Wednesday VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS AN Temple Pattarai PHC Kadampathur Pattarai village 0.3 km 532 Staffs VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN ICDS Madathukuppam PHC Vidaiyur Madathukuppam 0.5 km 510 Staffs 1st Thursday VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS AN ICDS Raman koil PHC Vidaiyur Raman koil 1.0 km 1141 Staffs VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN ICDS Veppanchetti PHC Vidaiyur Veppanchettai 0.2 km 494 Staffs 1st Friday CST Church Phillispuram PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS AN Phillispuram 0.2 km 455 Vidaiyur Staffs PU School Madurakandigai PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS 1st Saturday FN Madurakandigai & Chenji 0.2 km 345 Vidaiyur Staffs Hospital on wheels Programme (HoWP) - Microplan Block:KADAMBATHUR Week: 2 PHC to which HoWP is attached : Perambakkam Distance of the Camp Site ( Site, Village name and Name of the Villages to Population -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

University of Madras Institute of Distance Education Centre Notification May – June 2012 Examinations Chennai City Centres (Ug Degree Courses)

UNIVERSITY OF MADRAS INSTITUTE OF DISTANCE EDUCATION CENTRE NOTIFICATION MAY – JUNE 2012 EXAMINATIONS CHENNAI CITY CENTRES (UG DEGREE COURSES) S. No. CENTRE / VENUE EXAMINATIONS 1. J.H.A. Agarsan College, Manjambakkam B.Com – A11 and C11 Batches (Men and Road, Madhavaram, Chennai – 600 060. Women) Phone: 25559001 / 25559004 2. Thiruthangal Nadar College, Selavayal, B.Com – A10 & C10 Batches (All Chennai – 600051 (Near Kaviarasu Candidates Men & Women) Kannadasan Nagar Bus Depot) Phone: 25941717, 25942525, 25940393. 3. King’s Matriculation Higher Secondary B.Com – A9 & C9 Batches (Men and School, 85, Villivakkam Road, Women) Lakshmipuram Kalpalayam, Chennai – 600099. Phone: 25655709 / 25650348 4. I.D.P.L. Matric Higher Secondary School, B.Com – A7, A8, C7 & C8, X5 & X6 IDPL Township, Nandambakkam, Chennai Batches (All candidates Men & Women) – 600089. B.Sc. Geography – All Candidates Men Phone:22345534 & Women) 5. Shri Krishnaswamy College for Women, B.Com Old Batches up to X4 UCM / AC-48, 6th Main Road, Anna Nagar, SCM – All candidates Men & Women Chennai – 600040. Phone: 26282977 Bachelor of Multimedia and Animation (BMM) (All Batches Men and Women) 6. Alpha Arts and Science College, 16, B.B.A. – A11 & C11 Batches – (All College Road, Thundalam, Chennai – Candidates Men & Women) 600116. Phone: 24768656 7. Annai Violet Arts and Science College, B.B.A. – A10 & C10 Batches – (All No.53, Menambedu, Ambattur, Chennai – Candidates Men & Women) 600053. Phone: 26861611 / 26864684 B.A. Yoga for Human Excellence – (All Batches Men & Women) 8. Bhaktavatsalam Memorial College for BBA – A9 & C9 Batches – (Men and Women, No.14, 31st Street, Periyar Nagar, Women) Korattur, Chennai – 600 080. Phone: 26872891 9.