Creature Features and Consensus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Street Value for Viagra

GREAT SALE PRICES INSIDE! From the front cover: Brett Halsey: Art or Instinct in Movies NEW TITLES by John B. Murray - $25 Brett Halsey is mainly known for his work in Alfred Hitchcock’s London - $25 spaghetti Westerns and Italian adventure films, Gary Giblin takes film fans on a tour of but also classics like Return of the Fly and Return London locations used in Hitchcock films. to Peyton Place. When one examines Hollywood Whether a world traveler or armchair tour- and European genre movies together, it becomes ist you will enjoy this guided tour. clear that Brett Halsey has fashioned an impres- sive body of work. Forgotten Horrors 4 - $25 by Michael H. Price and John Wooley Classic Cliffhangers: Vol. 2 FH4 picks up where FH3 left off and cov- by Hank Davis - $25 ers the years 1947 and 1948. Titles include Volume 2 also allows us to examine titles made series such as Jungle Jim, the Falcon and during the Golden Era. Beginning in 1941, our Philo Vance, etc. $25 coverage includes serial gems like The Adven- tures of Captain Marvel, The Perils of Nyoka, Good Movies: Bad Timing - $25 Spy Smasher. Secret Service in Darkest Africa, Author Nicholas Anez examines films that and The Crimson Ghost—1941-1955 displays were considered box office duds but upon some of the finest actors, stuntmen and directors reevaluation prove to be decent films. In- to grace the screen. cludes James Bond and Tarzan, Hollywood’s Top Dogs Mantan the Funnyman - $35 by Deborah Painter - $25 by Michael H. Price [Includes a CD] The dog hero has existed in motion pictures for A biography of the great Mantan Moreland, over 100 years. -

William Witney Ùيلم قائمة (ÙÙŠÙ

William Witney ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… قائمة (ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… وغراÙÙ ŠØ§) Tarzan's Jungle Rebellion https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tarzan%27s-jungle-rebellion-10378279/actors The Lone Ranger https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-lone-ranger-10381565/actors Trail of Robin Hood https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/trail-of-robin-hood-10514598/actors Twilight in the Sierras https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/twilight-in-the-sierras-10523903/actors Young and Wild https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/young-and-wild-14646225/actors South Pacific Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/south-pacific-trail-15628967/actors Border Saddlemates https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/border-saddlemates-15629248/actors Old Oklahoma Plains https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/old-oklahoma-plains-15629665/actors Iron Mountain Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/iron-mountain-trail-15631261/actors Old Overland Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/old-overland-trail-15631742/actors Shadows of Tombstone https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shadows-of-tombstone-15632301/actors Down Laredo Way https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/down-laredo-way-15632508/actors Stranger at My Door https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/stranger-at-my-door-15650958/actors Adventures of Captain Marvel https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/adventures-of-captain-marvel-1607114/actors The Last Musketeer https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-last-musketeer-16614372/actors The Golden Stallion https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-golden-stallion-17060642/actors Outlaws of Pine Ridge https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/outlaws-of-pine-ridge-20949926/actors The Adventures of Dr. -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre. -

Bamcinématek Presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 Tales of Rampaging Beasts and Supernatural Terror

BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 tales of rampaging beasts and supernatural terror September 21, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, October 26 through Thursday, November 1 BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, a series of 10 films showcasing two strands of Japanese horror films that developed after World War II: kaiju monster movies and beautifully stylized ghost stories from Japanese folklore. The series includes three classic kaiju films by director Ishirô Honda, beginning with the granddaddy of all nuclear warfare anxiety films, the original Godzilla (1954—Oct 26). The kaiju creature features continue with Mothra (1961—Oct 27), a psychedelic tale of a gigantic prehistoric and long dormant moth larvae that is inadvertently awakened by island explorers seeking to exploit the irradiated island’s resources and native population. Destroy All Monsters (1968—Nov 1) is the all-star edition of kaiju films, bringing together Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra, and King Ghidorah, as the giants stomp across the globe ending with an epic battle at Mt. Fuji. Also featured in Ghosts and Monsters is Hajime Satô’s Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell (1968—Oct 27), an apocalyptic blend of sci-fi grotesquerie and Vietnam-era social commentary in which one disaster after another befalls the film’s characters. First, they survive a plane crash only to then be attacked by blob-like alien creatures that leave the survivors thirsty for blood. In Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku (1960—Oct 28) a man is sent to the bowels of hell after fleeing the scene of a hit-and-run that kills a yakuza. -

Dracula As Inter-American Film Icon: Universal Pictures and Cinematográfica ABSA

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar English, Linguistics, and Communication College of Arts and Sciences 2020 Dracula as Inter-American Film Icon: Universal Pictures and Cinematográfica ABSA Antonio Barrenechea Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/elc Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Review of International American Studies VARIA RIAS Vol. 13, Spring—Summer № 1 /2020 ISSN 1991—2773 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31261/rias.8908 DRACULA AS INTER-AMERICAN FILM ICON Universal Pictures and Cinematográfca ABSA introduction: the migrant vampire In Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), Jonathan Harker and the Tran- Antonio Barrenechea University of sylvanian count frst come together over a piece of real estate. Mary Washington The purchase of Carfax Abbey is hardly an impulse-buy. An aspir- Fredericksburg, VA ing immigrant, Dracula has taken the time to educate himself USA on subjects “all relating to England and English life and customs https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1896-4767 and manners” (44). He plans to assimilate into a new society: “I long to go through the crowded streets of your mighty London, to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life, its change, its death, and all that makes it what it is” (45). Dracula’s emphasis on the roar of London conveys his desire to abandon the Carpathian Mountains in favor of the modern metropolis. Transylvania will have the reverse efect on Harker: having left the industrial West, he nearly goes mad from his cap- tivity in the East. -

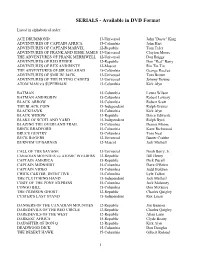

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

The Scream in 1950S American Science Fiction Film

MA MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER The Voice and the Void: The Scream in 1950s American Science Fiction Film Melissa Hergott Murray Pomerance The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joint Graduate Program in Communication & Culture Ryerson University - York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada 5 May2010 Table of Contents Chapter One: American Science Fiction Film and the 1950s ......................................................... 2 Chapter Two: Theorizing the Scream ........................................................................................... 20 Chapter Three: The Screaming Woman ....................................................................................... 35 Chapter Four: The Screaming Nlan ............................................................................................... 51 Conclusion: The Voice and the Void ............................................................................................ 67 \Vorks Cited .................................................................................................................................. 71 Filmography .................................................................................................................................. 74 . I - Chapter One: American Science Fiction Film and the 1950s In the United States, science fiction film rose to prominence as a critically recognized genre in the 1950s, a decade fraught with cultural complications and contradictions and also inspired -

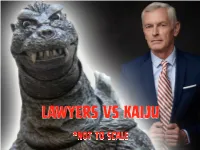

*Not to Scale Meet the Panel

Lawyers vs Kaiju *Not to Scale Meet the Panel Monte Cooper Jeraline Singh Edwards Joshua Gilliland Megan Hitchcock Matt Weinhold Does your Homeowner’s insurance cover being stepped on? Can Local Governments Recover Emergency costs? Public Expenditures Made in the Performance of Governmental Functions ARE NOT Recoverable! Is King Kong protected by the Endangered Species Act? Lawyers in the Mist A species is “endangered” if it is “in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” 16 U.S. CODE § 1532(6). A species is “threatened” if it is “likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” Id. § 1532(20); Conservation Force, Inc. v. Jewell, 733 F.3d 1200, 1202 (D.C. Cir. 2013). A species is considered “endangered” because of “natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.” 16 USCS § 1533(a)(1)(E). Is King Kong Protected by the Convention on International Trade in Protected Species (CITES)? CITES is a multi-lateral treaty originally negotiated among 80 countries in Washington DC in 1973 Subjects international trade in specimens of selected species to certain export and import controls As of 2018, 183 states and the European Union have become parties to the Convention Roughly 5,000 species of animals and 29,000 species of plants are protected by CITES Western Gorillas are specifically listed as subject to CITES BUT … King Kong in all incarnations is a new primate species, called Megaprimatus kong in 2005… King Kong Is a Critically Endangered Species When in New York … 1933 – Bad Things Happen to Kong in New York 1976 – Clearly, the Passage of the Environmental 2005 – The White House Still Does Not Species Act Did Not Help … Believe that Kong Needs Protection… Unfortunately for Kong, Skull Island Is Not a U.S. -

May 2021 New Releases

May 2021 New Releases SEE PAGE 58 what’s featured exclusives inside PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 73 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 16 FEATURED RELEASES Video THE RESIDENTS - ARISTOCRATS - ORIGINAL LONDON 46 GINGERBREAD MAN FREEZE! LIVE IN CAST RECORDING - Film EUROPE 2020 MEL BROOKS’ YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN Films & Docs 48 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 72 Order Form 77 Deletions & Price Changes 80 800.888.0486 12 MONKEYS STEELBOOK KINKY BOOTS THE FINAL COUNTDOWN 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 (3-DISC LIMITED EDITION/ www.MVDb2b.com 4K UHD+BLU-RAY+CD) SLY & ROBBIE - REGGAE: 999 - RED HILLS ROAD LIVE IN JAMAICA BEST OF LIVE KINKO DE MAYO! We kick off May with KINKY BOOTS on! KINKY BOOTS, the Tony Award winner for Best Musical opens in your home this month, with a DVD and Blu-ray release of the stage play! Written by Harvey Fierstein with music by Cyndi Lauper, the play finds an unlikely pair teaming up to create a line of sturdy stilettos that will put spring in your step! More musicals to our ears this month come in the twisted form of Mel Brooks’ Original London Cast Recording CD of YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN. Its Alive again as Dr. Fronkenstein, Inga, Frau Blucher and Eyegor sing and hump their way through the scariest comedy of all time! Hump? What hump? The legendary Christopher Lee may have never played a hunchback, but he has all other creepy bases covered in the nine- disc collection THE EUROCRYPT OF CHRISTOPHER LEE COLLECTION Blu-ray! Features five classic Lee European films, a TV anthology, rare interviews, a book and soundtrack CD. -

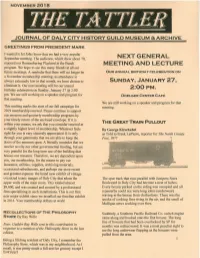

Next General Meeting and Lecture 2:00

NOVEMBER 20 t 8 JOURNAL OF DALY CITY HISTORY GUILD MUSEUM & ARCHIVE GREETINGS FROM PRESIDENT MARK I wanted to let folks know that we had a very popular. September meeting. The audience, which drew about 70, NEXT GENERAL enjoyed our Remembering Playland at the Beach MEETING AND LECTURE program. We hope to see this many friends at all our future meetings. A reminder that there will no longer be OUR ANNUAL BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION ON a November membership meeting; as attendance is always extremely low in that month, we have chosen to SUNDAY, JANUARY 27, eliminate it. Our next meeting will be our annual 2:00 PM. birthday celebration on Sunday, January 27 @ 2:00 pm. We are still working on a speaker and program for DOELGER CENTER CAFE that meeting. We are still working on a speaker and program for that This mailing marks the start of our fall campaign for meeting. 2019 membership renewal. Please continue to support our museum and quarterly membership programs by your timely return of the enclosed envelope. If it is THE GREAT TRAIN PULLOUT within your means, we ask that you consider renewal at a slightly higher level of membership. Whatever feels By George Kirschubel right for you is very sincerely appreciated. It is only as Told to Frank LaPierre, reporter for The North County through your generosity that we are able to keep the Post,1977 T doors of the museum open. A friendly reminder that we receive no city nor other governmental funding, but are very grateful for the long term use of the building that houses our museum. -

Creature Features. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 20P.; Developed at Hoover Junior High School, San Jose, Calif

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 092 973 CS 201 414 AUTHOR Carter, Candy TITLE Creature Features. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 20p.; Developed at Hoover Junior High School, San Jose, Calif. EDRS PRICE NF -$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Composition (Literary); *Course Content; Films; Grading; *Language Arts; *Performance Contracts; Reading; Research Projects; Secondary Education; Teaching Guides ABSTRACT Based on the contract grading system, this language arts course guide focuses on reading, writing, research, and film projects on topics which give people the "heebie- jeebies" and for uhich students earn points toward a final grade. Point values are dependent on the difficulty of the project or the length of the reading material. Contents of the guide include an introductory explanation of this contract course and its requirements; lists of project activities and their point values; a reading list, divided according to difficulty of material; rules for handling reading material:; reading review sheets; a list of writing activities; directions for research reports; sheets for movie reviews; an activity checklist; and samples of class games related to the projects. (JN) '44 Ii , ' ';', 4, 1 US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THiS DOCOVE HAS PE4IIi 1,;10 DUCE() E XACL V 45 IL (I VII) 404. : THE Pr 4S0% 041 04,...4%.74'1,0,4 AT,NG 1PC) '.1' S OP,N,Oh'.. S'ATEO DC NO1 %1C4 SSA41IL* 4F-P41 51%1 0, 1, IC 1:./. 1a..110,4t, 1.4S1 TUT r. EDuC P05.1,)", 041 PO CV BEST COPY MAILABLE St. :.1.76"4 r.'e 4:4 44'.,,, _p. -

PDF (1.01 Mib)

• Every Night i On Halloween night, punk gods The loween night. in the air, big "ISS" lighted letters were Misfits put on a spectacular show at a The show started off at 8:00 p.m. with wheeled out and a six-inch hand grinder packed House of Blues. The Misfits are the opening act Primitive Reason setting was set right under the main microphone. a band who initially thrived from '77 to the tone for the evening. The band came The show started with the five band mem- '83 with their original line-up of vocal- out in aboriginal paint schemes, which bers coming out on-stage in Rocky Hor- ist Glenn Danzig, bassist Jerry Only, matched their music well. Initially, Prim- ror style outfits with wigs and high heels. various guitarists includingJerry Only's' itive Reason seemed to be in the same Following closely behind the band were brother Doyle and a plethora of differ- vein as Soulfly, hard and heavy. They then two scantily clad women, who began ent drummers. They enjoyed moderate quickly switched to their true style of odd doing erotic dances to the rhythm of the success in the punk era of the late '70s, vocal stylings to groove style music. Many songs. Soon the pyros exploded right and established one of the most loyal of their songs even had a reggae feel. The behind the women and inside the bass fan-bases around. singer used a variety of odd instruments, drum, jump-starting the first song. For The band's image was based upon including bongos and a long woodwind their second song, The ISS セ ッ カ ・ イ ・ 、 Kiss' monsters and B-horror movies.