True-Bred Devonian Is Acquainted with Lydford; And, If in No Other Way, Through the Medium of That Most Popular Item of Western Proverbial Philosophy —Lydford Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Book of Dartmoor by the Same Author

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/bookofdartmoorOObaririch A BOOK OF DARTMOOR BY THE SAME AUTHOR LIFE OF NAPOLEON BONAPARTE THE TRAGEDY OF THE C^.SARS THE DESERT OF SOUTHERN FRANCE STRANGE SURVIVALS SONGS OF THE WEST A GARLAND OF COUNTRY SONG OLD COUNTRY LIFE YORKSHIRE ODDITIES FREAKS OF FANATICISM A BOOK OF FAIRY TALES OLD ENGLISH FAIRY TALES A BOOK OF NURSERY SONGS AN OLD ENGLISH HOME THE VICAR OF MORWENSTOW THE CROCK OF GOLD A BOOK OF THE WEST I. DEVON II. CORNWALL C 9 A BOOK OF DARTMOOR BY S. BARING-GOULD WITH SIXTY ILLUSTRATIONS NEW YORK: NEW AMSTERDAM BOOK CO. LONDON : METHUEN & CO. 1900 TO THE MEMORY OF MY UNCLE THE LATE THOMAS GEORGE BOND ONE OF THE PIONEERS OF DARTMOOR EXPLORATION ivii63832 PREFACE AT the request of my publishers I have written ^ ^ A Book of Dartmoor. I had already dealt with this upland district in two chapters in my " Book of the West, vol. i., Devon." But in their opinion this wild and wondrous region deserved more particular treatment than I had been able to accord to it in the limited space at my disposal in the above-mentioned book. I have now entered with some fulness, but by no means exhaustively, into the subject ; and for those who desire a closer acquaintance with, and a more precise guide to the several points of interest on "the moor," I would indicate three works that have preceded this. I. Mr. J. Brooking Rowe in 1896 republished the Perambulation of Dartmoor, first issued by his great- uncle, Mr. -

2020 Paignton

GUIDE 1 Welcome to the 2020 NOPS Kit Kat Tour Torbay is a large bay on Devon’s south coast. Overlooking its clear blue waters from their vantage points along the bay are three towns: Paignton, Torquay and Brixham. The bays ancient flood plain ends where it meets the steep hills of the South Hams. These hills act as suntrap, allowing the bay to luxuriate in its own warm microclimate. It is the bays golden sands and rare propensity for fine weather that has led to the bay and its seaside towns being named the English Riviera. Dartmoor National Park is a wild place with open moorlands and deep river valleys, a rich history and rare wildlife, making is a unique place and a great contrast to Torbay in terms of photographic subjects. The locations listed in the guide have been selected as popular areas to photograph. I have tried to be accurate with the postcodes but as many locations are rural, they are an approximation. They are not intended as an itinerary but as a starting point for a trigger-happy weekend. All the locations are within an hour or so drive from the hotel. Some locations are run by the National Trust or English Heritage. It would be worth being members or going with a member so that the weekend can be enjoyed to the full. Prices listed are correct at time of publication, concession prices are in brackets. Please take care and be respectful of the landscape around you. If you intend climbing or doing any other dangerous activities, please go in pairs (at least). -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P. -

Drewsteignton Parish

CROCKERNWELL Drewsteignton DREWSTEIGNTON S A N D Y P A R K VENTON WHIDDON DOWN Parish Post ISSUE NO. 63 APRIL 2011 MARCH NEWS FROM THE PARISH COUNCIL The Parish Council were saddened to hear Barry ernwell was received. Unless it served 200 ad- Colton had died suddenly at home and agreed a dresses and was not closer than 500 metres from letter of condolence should be sent to his family. another box, the Post Office would not place a He was a great friend to the community, helping new box there. If they received a complaint, how- to raise thousands of pounds for various organisa- ever, they would consider the reinstatement of tions in the Parish. the missing box. The Council resolved to make The allocation of the affordable housing at that complaint and await the outcome. We are Prestonbury View was a major topic. As reported also writing to Cheriton Bishop and Hittisleigh last month, Cllr Ridgers raised the subject with councils as this affects their parishioners as well. the Chief Executive of West Devon Borough It was noted in the Cheriton Bishop magazine Council and his reply acknowledged that mistakes that post boxes have gone missing without con- had been made and lessons should be learnt. sultation in their parish! Marion Playle, head of housing at WDBC, and Although some potholes have been filled in, there John Packer, the affordable housing champion for were many still to be attended to and we are WDBC, attended the meeting. Mr Packer con- pressing for them to be dealt with. -

A Perambulation of the Forest of Dartmoor Encircling the High Moor, This Historic Boundary Makes an Outstanding Walk

OUT AND ABOUT A Perambulation of the Forest of Dartmoor Encircling the high moor, this historic boundary makes an outstanding walk. Deborah Martin follows the trail of 12 medieval knights PHOTOGRAPHS FELI ARRANZ-FENLON, GEORGE COLES & DEBORAH MARTIN Historical Background The Perambulation is probably the oldest Our Walk of Dartmoor’s historical routes. It marks In May 2010 a group of us from the the boundary of the land that belonged Ramblers’ Moorland Group walked the to the Crown and was known as a forest Perambulation over three days with overnight because it comprised the King’s hunting stops. Doing it as a continuous walk has ground. Though Dartmoor Forest the advantage of gaining a perspective on originally belonged to the King, in 1337 the whole route, of ‘joining up the dots’ Edward III granted it to the Black Prince of the signifi cant features that mark out who was also Duke of Cornwall and it has the boundary. Though the knights of 1240 remained part of the Duchy of Cornwall ever since. started at Cosdon, we opted to begin at The Forest lies within the parish of Lydford and adjoins 21 other Dartmeet for practical reasons. May meant parishes, so there are numerous boundary stones around its long daylight hours – but would the weather borders. In order to mark out the line of the boundary various be kind? We knew there would be some Perambulations have taken place over the centuries, the earliest challenging terrain underfoot and numerous one recorded being in 1240. In that year the reigning King, Henry rivers to cross, so hopes were pinned on a III, despatched 12 of his knights to ride on horseback around the dry, clear spell. -

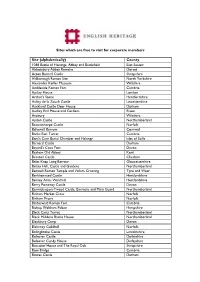

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Lydford Caravan & Camping Park Access Statement

Lydford Caravan & Camping Park Access Statement Site Address Lydford Caravan & Camping Park Lydford Nr. Okehampton Devon EX20 4BE Site Telephone Number and Website Address • Telephone number 01822 820497 • Website lydfordsite.co.uk Brief Site Description • Lydford Caravan and Camping Park is in a very quiet location close to Lydford village and enjoying excellent views of Dartmoor. Booking Information • Bookings can be made by calling the site direct, 01822 820497 or by completing the “on line booking” form at lydfordsite.co.uk or emailing for a booking form from [email protected] • Hearing or Speech impaired customers may care to make bookings via a Type Talk Operator. Arrival Information • The Site is mainly open with hedgerows and trees dividing main areas. • Roads of granite chippings service all parts of the site and a 5mph speed restriction is in place. • The approach to the site must be by following the described route. SatNav should not be used after leaving the A30 due to some narrow lanes. • Between 7.00am and 11.00pm the site is accessed via a security gate. Provision is made for pedestrian and wheelchair access at all times. • Between 11.00pm and 7.00am vehicle movement is prohibited on site, the main gate is locked and will only be opened in the event of an emergency. • Overnight parking is provided in the late arrivals and visitors parking area. • New arrivals should time their arrival between the hours of 12 noon and 8.00pm and before 7pm in low season. All unbooked 12 noon to 6pm only. Reception area information • Access to Reception is on one level at the site entrance. -

LYDFORD Guide £750,000

LYDFORD Guide £750,000 Larrick House Lydford EX20 4BJ Substantial Edwardian country house in a rural but not isolated position on the edge of Dartmoor Five Bedrooms - Master Ensuite Self-Contained Annexe Three Reception Rooms & Conservatory Grounds of Approx Three Acres, Including Gardens, Paddock & Woodland Driveway, Parking & Garage Super Views Guide £750,000 Bedford Court 14 Plymouth Road Tavistock PL19 8AY mansbridgebalment.co.uk 5+ 1 in Annexe 3+ 1 in Annexe 2+ 1 in Annexe SITUATION A substantial country house with annexe occupying its own extensive grounds and gardens, located in a rural, but not isolated, position on the edge of the Dartmoor National Park close to the popular village of Lydford and within easy reach of the popular market towns of Tavistock and Okehampton. In addition, the A30 dual carriageway provides a quick link into Cornwall or to Exeter to connect to the M5 motorway and fast inter City rail links to London, Bristol and the North. The city of Plymouth is 25 miles south with ferry services to Roscoff, Brittany and Santander, Northern Spain. Exeter and Newquay airports are less than 1 hour away and provide flights to London, UK provincial airports and international destinations. The ancient Stannary village of Lydford provides a full range of facilities including two inns, an active church, farm shop and primary school. The market towns of Tavistock (8 miles away) and Okehampton (10 miles away) both have ample shopping, educational and recreational facilities. There is a regular bus service to and from both Tavistock and Okehampton. Tavistock is a thriving market town adjoining the western edge of the Dartmoor National Park and was in 2004 voted the winner of a nationwide survey undertaken by the Council for the Protection of Rural England involving 120 other market towns. -

Tavistock World Heritage Site Key Centre Steering Group Interpretation Strategy

Tavistock World Heritage Site Key Centre Steering Group Interpretation Strategy Andrew Thompson January 2014 Tavistock Town Centre © Barry Gamble Contents Introduction p2 1. Statement of Significance p7 2. Interpretation Audit p13 3. Audience Research p22 4. Interpretive Themes p29 5. Standards for Interpretation p44 6. Recommendations p47 7. Action Plan p59 Appendix: Tavistock Statement of Significance p62 Bibliography p76 Acknowledgement The author is grateful to Alex Mettler and Barry Gamble for their assistance in preparing this strategy. 1 Introduction This strategy sets out a framework and action plan for improving interpretation in Tavistock and for enabling the town to fulfil the requirements of a Key Centre within the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site (WHS). It is intended to complement the Tavistock World Heritage Site Key Centre Learning Strategy (Kell 2013) which concentrates on learning activities and people. Consequently the focus here is primarily on interpretive content and infrastructure rather than personnel. Aims and objectives The brief set by the Tavistock World Heritage Site Key Centre Steering Group was to identify a consistent, integrated approach to presenting the full range of themes arising from the Outstanding Universal Value of WHS Areas 8, 9 and 10 and to respond to the specific recommendations arising from the WHS Interpretation Strategy (WHS 2005). We were asked to: x Address interpretation priorities in the context of the Cornish Mining WHS x Identify and prioritise target audiences x Set out a clearly articulated framework and action plan for the development of interpretation provision in WHS Area 10, including recommendations which address x Product development (i.e. -

Lydford Settlement Profile

r Lydford September 2019 This settlement profile has been prepared by Dartmoor National Park Authority to provide an overview of key information and issues for the settlement. It has been prepared in consultation with Parish/Town Councils and will be updated as necessary. Settlement Profile: Lydford 1 Introduction While set against a village history which is of great significance, the buildings of Lydford are, by and large, late, unremarkable and modest, both in size and architecture. What is remarkable about Lydford is its relative lack of modern development and therefore the preservation of its historic form. Settlement Profile: Lydford 2 Demographics A summary of key population statistics Population 409 Census 2011, determined by best-fit Output Areas Age Profile (Census 2011) Settlement comparison (Census 2011) 100+ Children Working Age Older People 90 Ashburton Buckfastleigh South Brent 80 Horrabridge Yelverton Princetown* 70 Moretonhampstead Chagford 60 S. Zeal & S. Tawton Age Mary Tavy Bittaford 50 Cornwood Dousland Christow 40 Bridford Throwleigh & Gidleigh 30 Sourton Sticklepath Lydford 20 North Brentor Ilsington & Liverton Walkhampton 10 Drewsteignton Hennock 0 Peter Tavy 0 5 10 15 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 Population * Includes prison population Population Settlement Profile: Lydford 3 Housing Stock Average House Prices 2016 Identifying Housing Need Excluding settlements with less than five sales, number of sales labelled following Parishes: Lustleigh 8 Christow 11 Lydford Yelverton 18 Manaton 8 Belstone 6 Chagford 22 Mary Tavy -

NEW MASTER FACTSHEET 1-04.Qxd

Farming on Dartmoor Dartmoor Factsheet Prehistoric times to the present day For over 5,000 years farming has been the Reaves are low, stony, earth covered banks main land use on Dartmoor. Working and which were built around 1200 BC to divide re-working the land, farmers have created all but the highest parts of Dartmoor, and maintained a large part of the Dartmoor first into territories (a little like our present landscape. Today over 90% of the land day parishes), and within those into long, within the National Park boundary is used narrow, parallel fields. Their main function for farming. Much of this area is both open was probably to control the movement of and enclosed moorland where livestock is stock, but there is some evidence that grazed, and the remainder is made up of prehistoric people were also growing fringe enclosed farmland which mainly cereals here. A climatic deterioration and the comprises improved grassland. In addition, spread of peat during the first millennium woods, shelterbelts, wetlands, rough pasture, BC (1000 - 1 BC), both resulting in poorer traditional buildings and archaeological grazing vegetation, contributed to the features all contribute to the character abandonment of the higher part of of the farmed land. Dartmoor during the later prehistoric period. The well-being of the hill farming community The Medieval Period is fundamental to the future of Dartmoor as a National Park in landscape, cultural, ecological Improvement of the climate in medieval times and enjoyment terms and for the viability and allowed the re-occupation of the moorland sustainability of the local rural community. -

Signed Walking Routes Trecott Inwardleigh Northlew

WALKING Hatherleigh A B C D E F G H J Exbourne Jacobstowe Sampford North Tawton A386 Courtenay A3072 1 A3072 1 Signed Walking Routes Trecott Inwardleigh Northlew THE Two MOORS WAY Coast Plymouth as well as some smaller settlements Ashbury Folly Gate to Coast – 117 MILES (187KM) and covers landscapes of moorland, river valleys and pastoral scenery with good long- The Devon Coast to Coast walk runs between range views. Spreyton Wembury on the South Devon coast and The route coincides with the Two Castles 2 OKEHAMPTON A30 B3219 2 Trail at the northern end and links with the Lynmouth on the North Devon coast, passing A3079 Sticklepath Tedburn St Mary through Dartmoor and Exmoor National Parks South West Coast Path and Erme-Plym Trail at South Tawton A30 Plymouth; also with the Tamar Valley Discovery Thorndon with some good or bad weather alternatives. B3260 Trail at Plymouth, via the Plymouth Cross-City Cross Belstone The terrain is varied with stretches of open Nine Maidens South Zeal Cheriton Bishop Stone Circle Whiddon Link walk. Bratton A30 Belstone Meldon Tor Down Crokernwell moor, deep wooded river valleys, green lanes Clovelly Stone s Row and minor roads. It is waymarked except where Cosdon Spinsters’ Drewsteignton DRAKE'S TRAIL Meldon Hill Rock it crosses open moorland. Reservoir Throwleigh River Taw River Teign Sourton West Okement River B3212 3 Broadwoodwidger Bridestowe CASTLE 3 The Yelverton to Plymouth section of the Yes Tor East Okement River DROGO Dunsford THE TEMPLER WAY White Moor Drake’s Trail is now a great family route Sourton TorsStone Oke Tor Gidleigh Row Stone Circle Hill fort – 18 MILES (29KM) High Hut Circles thanks to improvements near Clearbrook.