Understanding the Tipping Point of Urban Conflict: the Case of Patna, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India: Patna (Bihar) Hospital PPP

Public-Private Partnership Impact Stories India: Patna (Bihar) Hospital PPP Located in eastern India, Bihar is a low income state (LIS) with around 104 million people. According to the Government of India (GoI), over half the population is Below Poverty Line (BPL). In addition, the public health services in Bihar face severe constraints, especially lack of affordable specialty/tertiary care services. There are substantial gaps in health sector infrastructure and essential health requirements, including qualified staff, equipment, drugs, and consumables. As a result, people in the state have to travel to other states for their treatment. To help the state govern- ment improve access to, and availability of, advanced and affordable healthcare, IFC provided advisory assistance to the Government of Bihar and the state’s Infrastructure Development Authority (IDA), to structure and implement a public-private partner- ship (PPP) aimed at building, operating, and maintaining a greenfield super-specialty hospital in Patna, the capital city of the State of Bihar. The project was awarded on a competitive bid process to Global Health Patliputra Private Limited (GHPPL), a unit of Medanta the Medicity, one of India’s largest multi- super specialty hospitals. The concession agreement was signed with GHPPL on 22nd August 2015. The developer will develop the 500 bed super specialty hospital on Design, Build, Finance, Operate, & Transfer (DBFOT)) basis for a concession period of 33 years. This series provides an overview of public-private partnership stories in various infrastructure sectors, where IFC was the lead advisor. IFC’s advisory work was undertaken with financial support from the IFC Advisory Services in Public-Private Partnerships HANSHEP Health PPP facility funded by the UK’s Department for In- 2121 Pennsylvania Ave. -

Ground Water Year Book, Bihar (2015 - 2016)

का셍ााल셍 उप셍ोग हेतू For Official Use GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD जल ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पूर्वी क्षेत्र, पटना सितंबर 2016 MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA September 2016 ` GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES जल CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पर्वू ी क्षेत्र, पटना MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA सितंबर 2016 September 2016 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) CONTENTS CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables i List of Figures ii List of Annexures ii List of Contributors iii Abstract iv 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................1 2. HYDROGEOLOGY..........................................................................................................1 3. GROUND WATER SCENARIO......................................................................................4 3.1 DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL........................................................................................8 3.1.1 MAY 2015.....................................................................................................................8 3.1.2 AUGUST 2015..............................................................................................................10 3.1.3 NOVEMBER 2015........................................................................................................12 3.1.4 JANUARY 2016...........................................................................................................14 -

SOCIAL DYNAMIC STATUS and ITS REFLECTION on USE of FAMILY PLANNING METHODS in an INDIAN VILLAGE: the CASE of ‘GAURA’ VILLAGE (UP), INDIA Vimalesh Kumar Singh &

52/TheThe Third Third Pole, Pole Vol. 5-7, PP 52-61:2007 SOCIAL DYNAMIC STATUS AND ITS REFLECTION ON USE OF FAMILY PLANNING METHODS IN AN INDIAN VILLAGE: THE CASE OF ‘GAURA’ VILLAGE (UP), INDIA Vimalesh Kumar Singh &. M. B. Singh Department of Geography, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005, U P India [email protected] Abstract Present paper aims at examining the recent transformation of the village society, which is caste ridden, conservative and sluggish to adopt new innovations. The paper is mainly based on primary data collected through interview schedules from 80 families and 123 married women respondents on stratified random basis from Gaura village of Mirzapur District, Uttar Pradesh. On the basis of social dynamic status in a rural population of Gaura village the study pinpoints that Yadav, Gupta, Lohar, and Harijan (Scheduled caste) castes are static communities while Kurmi has been found single progressive caste. Brahmin and Kumhar are categorized as retrogressive castes. The paper also highlights the position of spouse on the practice of family planning methods. This study was undertaken to assess the extent of awareness among married women towards the various aspects of family planning. It was found that majority of the respondents had knowledge and awareness about various aspects of family planning but its adoption is of low magnitude. Women were the major users of permanently contraceptives (tubectomy) as contrary to men. Some women were found with the use of oral pills but the use of loops, condom and copper-T was almost absent in the study village. Key words: Family planning attitude, never users, contraceptives, caste, traditional social hierarchy. -

Diverse Genetic Origin of Indian Muslims: Evidence from Autosomal STR Loci

Journal of Human Genetics (2009) 54, 340–348 & 2009 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/09 $32.00 www.nature.com/jhg ORIGINAL ARTICLE Diverse genetic origin of Indian Muslims: evidence from autosomal STR loci Muthukrishnan Eaaswarkhanth1,2, Bhawna Dubey1, Poorlin Ramakodi Meganathan1, Zeinab Ravesh2, Faizan Ahmed Khan3, Lalji Singh2, Kumarasamy Thangaraj2 and Ikramul Haque1 The origin and relationships of Indian Muslims is still dubious and are not yet genetically well studied. In the light of historically attested movements into Indian subcontinent during the demic expansion of Islam, the present study aims to substantiate whether it had been accompanied by any gene flow or only a cultural transformation phenomenon. An array of 13 autosomal STR markers that are common in the worldwide data sets was used to explore the genetic diversity of Indian Muslims. The austere endogamy being practiced for several generations was confirmed by the genetic demarcation of each of the six Indian Muslim communities in the phylogenetic assessments for the markers examined. The analyses were further refined by comparison with geographically closest neighboring Hindu religious groups (including several caste and tribal populations) and the populations from Middle East, East Asia and Europe. We found that some of the Muslim populations displayed high level of regional genetic affinity rather than religious affinity. Interestingly, in Dawoodi Bohras (TN and GUJ) and Iranian Shia significant genetic contribution from West Asia, especially Iran (49, 47 and 46%, respectively) was observed. This divulges the existence of Middle Eastern genetic signatures in some of the contemporary Indian Muslim populations. -

Afu Srd Qoffir

qeio-ftocogofroelo/ lRMs- 10/2020, qi"...1.?.... fe-ax tcnffft-o gan frvn ffi (qrqrq s$rsq frqrrr) nso', sfi{r ts{ fu€r. frts o,d c-{ffi. ftErq crrfifto gun frvr ffi qe-+t ftr n, ftrm q-flDorfr. qfiIt qr.n. ftci--...a >ll.g.l.l..t:^ ftqq:- qrc-q ssrEFr c-{'Er{ c"nd (HRMS) clMn t-{r gkorot ovn rgqtqun-sqa iD't Scanning d tidq { t q{frl:- fr{H qr qiw-''titz. fr{ifr-1s.io.2o1s aefl q{i6-gol. fr{is- 29.05.2020 IT6ITq, sqEffi frqq-o' crciFro q'it d snr enc si-{q-d t fu rrq ofid oI \1otq-d srcrn{ d-fi oa qFit qa or eR-o G crrflff $ffiq-qf, qr+q \4qErt !-qtrr cqrfr (HRMs) ffi( o-{i d mq d fu S*Zo* qms q'r Digitisation aeTI e-tar gw ot ffiu fu sqcIcr qtrqr"qt (legacy oata) fr Data capture Format (DCFIi cfre o'-{i or ord srt i t 2. -cniFro' c=jl n +sI gRilor. ridl= 3IRs st 6ffi{it ErqI sqnrq orri rrc Efrqw q, ol Scanning 6{i d €dtl I arerrl i] oTd-6q +1 qaw frn qri ot s-de fu-ql .rqr t t q-c-{ o. tfl Sfu"ol r{ €dcun qr d scanning t-E ftrd d orufa-q-qR aTtroq frt q.ff *ia.{ tr (3r-flff-r) 4- Scanning 61 o,rd qqF-( 1'Ss lvs CBSL eRI ffiqr .rfi. f,a, 3Tq{ qfoq. .rfi Fmfur fuTFr d ory S qmi srd o.rt it ftcio-oa.o'r.zoz'r d qrtqt"-gef ro:oo ad t 3rq{rfl 6:00 cd ao ria.c o'd-6'q F-5{ff-r) o r5wn fu-qI qrvqrt 5. -

Demp Kaimur (Bhabua)

DEMP KAIMUR (BHABUA) SL SUBJECT REMARKS NO. 1 2 3 1. DISTRICT BRIEF PROFILE DISTRICT POLITICAL MAP KEY STATISTICS BRIEF NOTES ON THE DISTRICT 2. POLLING STATIONS POLLING STATIONS LOCATIONS AND BREAK UP ACCORDING TO NO. OF PS AT PSL POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-ACCESSIBILITY POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-TELECOM CONNECTIVITY POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-BASIC MINIMUM FACILITIES POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-INFRASTRUCTURE VULNERABLES PS/ELECTIORS POLLING STATION LOCATION WISE ACCESSIBILITY & REACH DETAILS POLLING STATION WISE BASIC DETAISLS RPOFILING AND WORK TO BE DONE 3. MANPOWER PLAN CADRE WISE PERSONNEL AVAILABILITY FOR EACH CATEGORY VARIOUS TEAMS REQUIRED-EEM VARIOUS TEAMS REQUIRED-OTHERS POLLING PERSONNEL REQUIRED OTHER PERSONNEL REQUIRED PERSONNEL REQUIRED & AVAILABILITY 4. COMMUNICATION PLAN 5. POLLING STAFF WELFARE NODAL OFFICERS 6. BOOTH LIST 7. LIST OF SECTOR MAGISTRATE .! .! .! .! !. .! Assembly Constituency map State : BIHAR .! .! District : KAIMUR (BHABUA) AC Name : 205 - Bhabua 2 0 3 R a m g a r h MOHANIA R a m g a r h 9 .! ! 10 1 2 ! ! ! 5 12 ! ! 4 11 13 ! MANIHAR!I 7 RUP PUR 15 3 ! 14 ! ! 6 ! 8 73 16 ! ! ! RATWAR 19 76 ! 2 0 4 ! 18 .! 75 24 7774 17 ! M o h a n ii a (( S C )) ! ! ! 20 23 DUMRAITH ! ! 78 ! 83 66 21 !82 ! ! .! 32 67 DIHARA 22 ! ! 68 ! 30 80 ! 26 ! 31 79 ! ! ! ! 81 27 29 33 ! RUIYA 70 ! 25 ! 2 0 9 69 ! 2 0 9 KOHARI ! 28 KAITHI 86 ! K a r g a h a r 85 ! 87 72 K a r g a h a r ! ! 36 35 ! 71 60 ! ! ! 34 59 52 38 37 ! ! ! ! 53 KAIMUR (BHABUA) BHABUA (BL) 64 ! ! 40 84 88 62 55 MIRIA ! ! ! ! BAHUAN 54 ! 43 39 !89 124125 63 61 ! ! -

Brief Industrial Profile of Bhojpur District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Bhojpur District Carried out by MSME -Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Patliputra Industrial Estate, PATNA - 800013 Phone: 0612-2262186/2262208/2262719 Fax: 0612=2262186 e-mail: [email protected] Web-www.msmedipatna.gov.in 1 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 03 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 03 1.2 Topography 03 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 03 1.4 Forest 04 1.5 Administrative set up 04 2. District at a glance 04 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District Bhojpur 07 3. Industrial Scenario Of Bhojpur 07 3.1 Industry at a Glance 07 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 08 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 09 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 09 3.5 Major Exportable Item 09 3.6 Growth Trend 09 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 10 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 10 3.8.1 List of the units in Bhojpur & near by Area 10 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 10 3.9 Service Enterprises 10 3.9.1 Coaching Industry == 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 10 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 10 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 10 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 10 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 10 4.1.2 Service Sector 11 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 11 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 12 meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 13 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Bhojpur District 1. -

GIPE-039453.Pdf (2.380Mb)

Ct>NSTI:CUENT ASSEMBLY OF . tlNDIA EXCLUDED AND PARTIALLY EXCLUDED AREAS (OTHER THAN ASSAM) SUB-COM~TTEE Volume I (Report) V2:2.N471t "iGIIB, GOQ:IUllaliiT ur lsl>IA Pn&sa, Nrnr Bam, ......_ H7 r $47 • 039453 uoL'D'»E» u» PARTIALLY ~ll'Du- AREAs -comia:a TJUJf · ASS~ S'D',B·OOIOII'l"l'JIE, 'l~ui>-Committee I 1. Shri A. V. Thakkar--Chairman. Members: ' 2. Shri J aipal Singh . .S. Shri Devendra Nath Samanta. 4-. Shri Phul Bhanu Shah . .6. The Hon 'ble Shri J agjivan Ram. 6. The Hon 'ble Dr. Profulla Chandra Ghooh. 7. Shri Raj Kruohna Bose. Co-opted Membero : 6. Shri Khetramani Panda-Phulbani Area. 9. Shri Sadasiv Tripathi-Orissa P. E. Areas. 10. Shri Kodanda Ramiah-Madras P. E. Areas. 11. Shri Sneha Kumar Chalone Chittagong Rill Traota. 12. Shri Dumber Singh Gurung-Darjeeling ;District. · Secretary: 18. Mr. R. K. Ramadhyani, ·J.C.S. EKOL'DDBD AND PARTIALLY EXCLUDED AREAS (O'rlllm mAN ASSAJI) SUB-COIIIMlTlEE. Index· SubJect Letter from Cba.irman, Excluded & Ps.rtisJly Exoluded ,Areas (other. than Assam) Sub-Committee to the Chairman Advisory Co'Timitlee INTERIM REPORT Para. Page· 1. INTRODUOTORY 1 2. EXOLUDED AREAs:-. ll (a) Madras I (b) Punjab • .~.• s (o) Bongo! , I 8, PARTlALLYEXOLUDEDAREAS: . , • 8 {a) ltadras " • (b) Bombay , • .. ' (o) Oen£ra1 Provinces & Berar • '6- (d) Orissa .8· (e) Bengal, • 't . (f) Bihar 8· (g)· United Pl'Ovmcea I 4. POLITICAL EXPERIENOE .. - . • lG G, EFFEOTS OF EXOLUBION Io- e. A'l'l'l'ruDE OF THE GENERAL PUBLIO 11 7, POTENTIALITIES OF THE TRIBES , 11 8, GENERAL CONOLUBIONS • 11 9. -

State District Name of Bank Bank Branch/ Financial Literacy Centre

State District Name of Bank Branch/ Address ITI Code ITI Name ITI Address State District Phone Email Bank Financial Category Number Literacy Centre Bihar Araria State Araria Lead Bank Office, PR10000055 Al-Sahaba Industrial P Alamtala Forbesganj Bihar Araria NULL Bank of ADB Building, Training Institute India Araria, Pin- 854311 Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000083 Adarsh ITC P Umerabad Bihar Arwal NULL Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000284 Shakuntalam ITC P Prasadi English Bihar Arwal NULL Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000346 Aditya ITC P At. Wasilpur, Main Road, Bihar Arwal NULL P.O. Arwal, Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000396 Vikramshila Private P At. Rojapar, P.O. Arwal Bihar Arwal NULL ITI Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000652 Ram Bhaman Singh P At-Purani Bazar P.o+P.S- Bihar Arwal NULL Private ITI Arwal Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000677 Sukhdeo Institute Of P Kurtha, Arwal Bihar Arwal NULL Tecnology Private ITI, Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000707 Dr. Rajendra Prasad P Mubarkpur, Kurtha Arwal Bihar Arwal NULL Private ITI, Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000027 New Sai Private ITI- P Aurangabad Road, Bihar Aurangabad NULL NATIONA Bhakharuan More, , Tehsil- L BANK Daudnagar , , Aurangabad - 824113 Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB AURANGABAD AURANGABAD PR10000064 Adharsh Industrial P Josai More Udyog Bihar Aurangabad NULL NATIONA Training Centre Pradhikar Campus L BANK Bihar Aurangabad MADHYA DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000108 Sardar Vallabh Bhai P Daudnagar Bihar Aurangabad NULL BIHAR Patel ITC, Daudnagar GRAMIN BANK Bihar Aurangabad MADHYA DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000142 Adarsh ITC, P AT-,Growth centre ,Jasoia Bihar Aurangabad NULL BIHAR Daudnagar More Daudnagar GRAMIN BANK Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB RATANUA RATANUA PR10000196 Progresive ITC P At-Growth Center Josia Bihar Aurangabad NULL NATIONA More L BANK Bihar Aurangabad MADHYA DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000199 Arya Bhatt ITC P Patel Nagar, Daud Nagar Bihar Aurangabad NULL BIHAR GRAMIN BANK Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB OLD GT RD. -

Block: Piro Class-6-8 Subject: Social Science Dist:-Bhojpur Provisional Merit List Block Teacher Niyojan-2019-20

BLOCK TEACHER NIYOJAN-2019-20 BLOCK: PIRO CLASS-6-8 SUBJECT: SOCIAL SCIENCE DIST:-BHOJPUR PROVISIONAL MERIT LIST 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 MATRIC INTER GRADUATION TRAINING FREE BTET/CT WEIG SUM OF AVG OF TAGE APPL.S. NAME OF SE D. FUL MARK ET TOTAL S.N. FATHER DOB ADDRESS CAT DIS. MARKS MARKS FULL MARKS FULL FULL PERCENT PERCEN OF REMARKS N. APPLICANT X FIGH L S MARKS MERIT OBTAI %GE OBTAIN MARK %GE OBTAINE MARK %GE MARK %GE AGE TAGE BTET/ T. MAR OBTAI % NED ED S D S S CTET KS NED MOHD ARANGI-01 NAZIA 1 1776 MONIR 18/4/1995 F USIA UR N N 457 500 91.4 434 600 72.3333 3330 4500 74 1675 2000 83.75 321.4833 80.37 62.66 2 82.371 MONIR ANSARI GHAZIPUR DAYASHAN PRAGYA KAILASHPUR 2 P/197 KAR 22/12/1996 F EWS N N 409 500 81.8 432 500 86.4 740 1000 74 762 1000 76.2 318.4 79.60 68 2 81.6 PANDEY I BUXAR PANDEY NEERAJ BHRIGUNA BIHIYA 3 976 KUMAR 02.01.1993 M UR N N 403 500 80.6 413 500 82.6 964 1500 64.2667 1064 1300 81.8462 309.3128 77.33 72.41 4 81.328 TH MISHRA BHOJPUR MISHRA SHREE DEVRADH, SUNITA 4 1785 DHAR 03.01.1986 F TIYAR, EWS N N 537 700 76.7143 683 900 75.8889 1179 1500 78.6 1054 1300 81.0769 312.2801 78.07 55.33 2 80.07 KUMARI DUBEY BHOJPUR VIPUL NAWAL GAUSGANJA 5 1770 KUMAR KISHOR 01.04.1979 M UR N N 711 900 79 693 900 77 1177 1500 78.4667 1834 2400 76.4167 310.8833 77.72 62.66 2 79.721 RA SINGH SINGH DHAMANIA, HIMANSHU RAMESHW 6 424 26/01/1996 M GARAHANI, EBC N N 419 500 83.8 350 500 70 722 1000 72.2 998 1300 76.7692 302.7692 75.69 70.67 4 79.692 SHEKHAR AR PRASAD BHOJPUR ROHAI, ASHWANI -

Constituent Assembly Debates Official Report

Volume VII 4-11-1948 to 8-1-1949 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT REPRINTED BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI SIXTH REPRINT 2014 Printed by JAINCO ART INDIA, New Delhi CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA President : THE HONOURABLE DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD Vice-President : DR. H.C. MOOKHERJEE Constitutional Adviser : SIR B.N. RAU, C.I.E. Secretary : SHRI H.V. IENGAR, C.I.E., I.C.S. Joint Secretary : SHRI S.N. MUKERJEE Deputy Secretary : SHRI JUGAL KISHORE KHANNA Under Secretary : SHRI K.V. PADMANABHAN Marshal : SUBEDAR MAJOR HARBANS RAI JAIDKA CONTENTS ————— Volume VII—4th November 1948 to 8th January 1949 Pages Pages Thursday, 4th November 1948 Thursday, 18th November, 1948— Presentation of Credentials and Taking the Pledge and Signing signing the Register .................. 1 the Register ............................... 453 Taking of the Pledge ...................... 1 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 453—472 Homage to the Father of the Nation ........................................ 1 [Articles 3 and 4 considered] Condolence on the deaths of Friday, 19th November 1948— Quaid-E-Azam Mohammad Ali Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 473—500 Jinnah, Shri D.P. Khaitan and [Articles 28 to 30-A considered] Shri D.S. Gurung ...................... 1 Amendments to Constituent Monday, 22nd November 1948— Assembly Rules 5-A and 5-B .. 2—12 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 501—527 Amendment to the Annexure to the [Articles 30-A, 31 and 31-A Schedule .................................... 12—15 considered] Addition of New Rule 38V ........... 15—17 Tuesday, 23rd November 1948— Programme of Business .................. 17—31 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 529—554 Motion re Draft Constitution ......... 31—47 Appendices— [Articles 32, 33, 34, 34-A, 35, 36, 37 Appendix “A” ............................. -

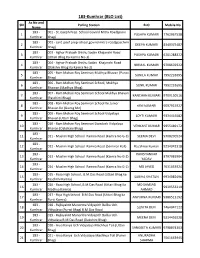

183-Kumhrar (BLO List) Ac No and Sl# Polling Station BLO Mobile No Name 183 - 001 - St Joseph Prep

183-Kumhrar (BLO List) Ac No and Sl# Polling Station BLO Mobile No Name 183 - 001 - St Joseph Prep. School Govind Mitra Road(purvi 1 PUSHPA KUMARI 7762067538 Kumhrar bhag) 183 - 002 - sant josef prep school,govind mitra road(paschimi 2 DEEPA KUMARI 8340375487 Kumhrar bhag) 183 - 003 - Aghor Prakash Shishu Sadan Khajanchi Road 3 PUSHPA KUMARI 6201288322 Kumhrar (Uttari Bhag Ka Kamra No-3) 183 - 004 - Aghor Prakash Shishu Sadan Khajanchi Road 4 NIRMAL KUMARI 9708602922 Kumhrar (Dakshni Bhag Ka Kamra No-2) 183 - 005 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari Mukhya Bhavan (Purwi 5 SUNILA KUMAR 7992231695 Kumhrar Bhag) 183 - 006 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School, Mukhya 6 SUNIL KUMAR 7992231695 Kumhrar Bhawan (Madhya Bhag) 183 - 007 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School Mukhya Bhavan 7 KANCHAN KUMARI 9709150516 Kumhrar (Paschimi Bhag) 183 - 008 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School Ke Junior 8 rANI kUMARI 9097915927 Kumhrar Bhavan Ke (Gairag Me) 183 - 009 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School Vidyalaya 9 JOYTI KUMARI 9334416582 Kumhrar Bhavan (Uttari Bhag) 183 - 010 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari Dwadash Vidyalaya 10 VENKANT KUMAR 9955489172 Kumhrar Bhavan (Dakshani Bhag) 183 - 11 011 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Kamra No G-3) SEEMA DEVI 9708200524 Kumhrar 183 - 12 012 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Seminar Hall) Raj Shree Kumari 9234342318 Kumhrar 183 - RAVISHANKAR 13 013 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Kamra No G-2) 8797983904 Kumhrar YADAV 183 - 14 014 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Kamra No G-1) MD JAVED 7631653924 Kumhrar 183 - 015 - Raza High School , B.M.Das Road (Uttari