The Baroque Period, Part 2: Developments in Instrumental Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining the Performance Practice of Polyphonic Figures in J.S

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2011 Chord Conundrum: Examining the Performance Practice of Polyphonic Figures in J.S. Bach's Solo Violin Works Emily Vold Columbus State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Vold, Emily, "Chord Conundrum: Examining the Performance Practice of Polyphonic Figures in J.S. Bach's Solo Violin Works" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 107. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/107 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. .5 .it* v fif'-j 'wr i7 I' U5" Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/chordconundrumexOOvold Chord Conundrum: Examining the Performance Practice of Polyphonic Figures in J.S. Bach's Solo Violin Works by Emily Void A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the Bachelor of Music in Music Performance College of the Arts Columbus State University Thesis Advisor JjJjUkAu Date ¥/&/// Committee Member Date Committee MembeC^^^^^ J^C^^~^ Date J^g> *&&/ / CSU Honors Committee Member Date Director, Honors Program (^Ljjb^Q^/^ ^—^O Date J^r-ste// Interpreting and expressing the musical intentions of a composer in an informed manner requires great dedication and study on the part of a performer. This holds particularly true in the case of music written well before the present age, where direct connections to the thoughts of the composer and even the styles of the era have faded with the passing of time. -

Corelli'stonalmodels

Intégral 31 (2017) pp. 31–49 Corelli's Tonal Models: The Trio Sonata Op.3, No. 1* by Christopher Wintle Abstract. British thought is typically pragmatic, so a British reception of the work of Heinrich Schenker will concern itself with concrete procedure at the expense of hypothetical abstraction. This is especially important when dealing with the work of Arcangelo Corelli, whose work, along with that of others in the Franco-Italian tradi- tion, holds the key to common-practice tonality. The approach of the British author is thus to construct a set of concrete linear-harmonic models derived from the fore- ground and middleground techniques of Schenker and to demonstrate their han- dling throughout the four movements of a representative trio sonata (Op. 3, No. 1). In this essentially “bottom-up” project, detailed discussion of structure readily merges into that of style and genre, including dance and fugue. The text is supported by many examples and includes a reprint of the trio sonata itself. Keywords and phrases: Arcangelo Corelli, Heinrich Schenker, trio sonata, tonal models, fugue. Introduction poser or a single school,” nevertheless suggested that it was Corelli who “was the first to put the tonal formu- here appears to have been no doubt in the minds of las to systematic use.” Christopher Hogwood (1979, 41), on T many of those who have written about the Baroque the other hand, cites two eighteenth-century sources to era that the music of Arcangelo Corelli bore an extraordi- suggest that Corelli’s achievement was one more of man- nary significance, and one that extended far beyond his ner than of matter: according to Charles Burney, he says, having made a remarkable contribution to the repertoire “Corelli was not the inventor of his own favorite style, of solo, chamber, and concerted violin music. -

15. Corelli Trio Sonata in D, Op. 3 No. 2: Movement IV

15. Corelli Trio Sonata in D, Op. 3 No. 2: Movement IV (For Unit 6: Further Musical Understanding) Background information and performance circumstances Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) is one of the most important and influential composers of the Baroque period. This is all the more remarkable for the fact that his output was very small, being just four sets of twelve trio sonatas, twelve solo sonatas and twelve concerti grossi, plus a handful of other works. All of his music was written for instrumental forces (almost entirely string ensemble) and the form and style of these works were highly regarded by the later generation of Baroque composers such as Handel and Bach. His music was widely recognised and circulated through publishing with as many as 35 different editions of his Op.1 Trio Sonatas being published during the eighteenth-century alone. The compositional techniques Corelli employed are frequently cited as a model for students of Baroque counterpoint and harmony today. Corelli was born into a prosperous landowning family in Fusignano in Northern Italy, although sadly his father died before Arcangelo was born. He studied for four years at nearby Bologna at a time when Italians reigned as the best instrument makers, teachers and performers of string music in the whole of Europe. In 1675, he moved to Rome where he remained for the rest of his life earning his living as a violinist and composer. Queen Christine of Sweden was an early patron of Corelli (he dedicated his Op.1 Trio Sonatas to her) but the Op.3 Trio Sonatas were dedicated in 1689 to Duke Francesco II of Modena. -

A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’S Clarinet Sonata

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata Kenneth T. Aoki Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Composition Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation Aoki, Kenneth T., "A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1077. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1077 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SONATA WITH AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF A BRAHMS' AND HINDEMITH'S CLARINET SONATA A Covering Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Education by Kenneth T. Aoki August, 1968 :N01!83 i iuJ :JV133dS q g re. 'H/ £"Ille; arr THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CENTRAL WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGE presents in KENNETH T. AOKI, Clarinet MRS. PATRICIA SMITH, Accompanist PROGRAM Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in B flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2. J. Brahms Allegro amabile Allegro appassionato Andante con moto II Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano .............................................. 8. Heiden Con moto Andante Vivace, ma non troppo Caprice for B flat Clarinet ................................................... -

Arcangelo Corelli

Arcangelo Corelli The music of Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) exerted an influence on the development of string music that far exceeded the implications of the modest number of prints in which they were circulated. Only six volumes of works, each containing twelve sonatas or concertos, were published, and the last after Corelli’s death. Corelli’s fame emanated from his playing in Rome, where the courts of cardinals offered much of the best, and best supported, music. Corelli’s particular patrons and benefactors included Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili and his successor, Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni as well as the exiled queen Christina of Sweden. His popularity in the eighteenth century (much of it posthumous) was immense. Printed copies of his works from that time are widely spread throughout Europe, North America, and the East Asia. Church and Chamber Sonatas Opp.1-4 The first four of Corelli’s volumes contains “trio” sonatas—sonatas for two violins and basso continuo. In the case of the “church” sonatas (sonate da chiesa; Opp. 1 [1681] and 3 [1689] ), the works were usually accompanied by organ, which would be reinforced by a cello or a lute or both. In contrast, “chamber” sonatas (sonate da camera, Opp. 2 [1685] and 4 [1692] ) were accompanied by harpsichord, often reinforced by cello. According to long-held views, the difference between church and chamber sonatas inhered in their structure and content. Church sonatas typically contained four movements in the sequence slow-fast- slow-fast (e.g., Adagio-Allegro-Adagio-Allegro). Imitative writing could occur between treble and bass instruments or between the two violins. -

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano A Performance Edition with Commentary D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Antoine Terrell Clark, M. M. Music Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Approved By James Pyne, Co-Advisor ______________________ Co-Advisor Lois Rosow, Co-Advisor ______________________ Paul Robinson Co-Advisor Copyright by Antoine Terrell Clark 2009 Abstract Late Baroque works for string instruments are presented in performing editions for clarinet and piano: Giuseppe Tartini, Sonata in G Minor for Violin, and Violoncello or Harpsichord, op.1, no. 10, “Didone abbandonata”; Georg Philipp Telemann, Sonata in G Minor for Violin and Harpsichord, Twv 41:g1, and Sonata in D Major for Solo Viola da Gamba, Twv 40:1; Marin Marais, Les Folies d’ Espagne from Pièces de viole , Book 2; and Johann Sebastian Bach, Violoncello Suite No.1, BWV 1007. Understanding the capabilities of the string instruments is essential for sensitively translating the music to a clarinet idiom. Transcription issues confronted in creating this edition include matters of performance practice, range, notational inconsistencies in the sources, and instrumental idiom. ii Acknowledgements Special thanks is given to the following people for their assistance with my document: my doctoral committee members, Professors James Pyne, whose excellent clarinet instruction and knowledge enhanced my performance and interpretation of these works; Lois Rosow, whose patience, knowledge, and editorial wonders guided me in the creation of this document; and Paul Robinson and Robert Sorton, for helpful conversations about baroque music; Professor Kia-Hui Tan, for providing insight into baroque violin performance practice; David F. -

Baroque Violin Sonatas

Three Dissertation Recitals: the German Romanticism in Instrumental Music and the Baroque Instrumental Genres by Yun-Chie Wang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music Performance) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Aaron Berofsky, Chair Professor Colleen M. Conway Professor Anthony Elliott Assistant Professor Joseph Gascho Professor Vincent Young Yun-Chie (Rita) Wang [email protected] ORCID id: 0000-0001-5541-3855 © Rita Wang 2018 DEDICATION To my mother who has made sacrifices for me every single day To my 90-year old grandmother whose warmth I still carry ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members for helping me become a more thoughtful musician. I would like to give special thanks to Professor Aaron Berofsky for his teaching and support and Professor Joseph Gascho for his guidance and collaboration. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF FIGURES v ABSTRACT vi Dissertation Recital No. 1 Beyond Words Program 1 Program Notes 2 Dissertation Recital No. 2 Baroque Violin Sonatas Program 13 Program Notes 14 Dissertation Recital No. 3 Baroque Dances, a Fugue, and a Concerto Program 20 Program Notes 22 BIBLIOGRAPHY 31 iv LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page Fig. 1, The engraving of the Guardian Angel (printed in the manuscript of the Mystery Sonatas by Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber) 27 Fig. 2, Opening measures of the fugue from Op. 10, No. 6 by Bartolomeo Campagnoli 29 Fig. 3, Opening measures of the fugue from Sonata No. 3, BWV 1005, by J. -

Western Culture Has Roots in Ancient

29 15. Know the structure of the da capo aria (including keys). Statement: The one described on p. 383 is called a five- Chapter 17 part da capo aria. It's also possible to have just an ABA Italy and Germany in the type, too. Late Seventeenth Century 16. (382) What is a serenata? Composer? 1. (379) How did Italy and Germany differ from other Semidramatic piece for several singers with small orchestra; countries? So what? Alessandro Stradella They had a number of sovereign states; no center for musical activity so there were many places 17. (383) Describe church music styles and composer cited. Old Palestrina style with the newer concerted styles; Maurizio 2. What were the various influences? Cazzati In Italy, it was native music and its evolution; in Germany it was Italian and French styles 18. (384) Bologna was also important for what else? Instrumental ensemble music (often played in church) 3. (380) Where did most of the major developments in Italy take place? 19. What did organ composers write? The north Ricercares, toccatas, variation canzonas, chant settings 4. Where are the major centers of opera? Who are the 20. What are characteristics of the oratorio? composers? Italian text, had verse instead of poetry, in two sections Venice, Naples, Florence, Milan; Giovanni Legrenzi at Ferrara and Alessandro Scarlatti at Rome and Naples 21. Name the violin makers. Nicolò Amati, Antonio Stradivari, Giuseppe Bartolomeo 5. What attracted audiences the most? Guarneri Star singer and arias 22. Describe the sonata before 1650. Composer? 6. How many arias in an opera before 1670? After? Small sections differing in theme, texture, mood, character, 24; 60 and sometimes meter and tempo; Biagio Marini 7. -

Y10 GCSE Music Musical Periods KO Cycle 1

MUSIC HISTORY – MUSICAL PERIODS SUMMARY KNOWLEDGE ORGANISER The Baroque Period The Classical Period The Romantic Period (1600-1750) (1750-1820) (1820-1900) Baroque music sounDs ORNATE, DECORATED anD Classical music sounDs BALANCED, ELEGANT, Romantic music sounDs LYRICAL, EMOTIONAL, DRAMATIC EXTRAVAGANT ORDERED anD SYMMETRICAL anD DESCRIPTIVE THEMES – much music baseD on an emotion, place, dreams, ORNAMENTS – Decorations aDDeD to the meloDies BALANCED REGULAR PHRASES (4 anD 8 bars) the supernatural or stories POLYPHONIC TEXTURE – Dense overlapping with HOMOPHONIC TEXTURE – clear meloDy with an LEITMOTIFS – short melodies linked to a character or lots of interweaving melodies accompaniment emotions EXTRAVAGANT DYNAMICS – extremes useD to portray th rd th IMITATION anD SEQUENCE ALBERTI BASS – Pattern of Root, 5 , 3 , 5 as an intense emotion accompaniment TERRACED DYNAMICS – either louD or soft CHROMATICISM – use of notes outsiDe the key to create DISSONANCE FUNCTIONAL HARMONY – clear keys, cadences TIMBRE & SONORITY – mainly strings, simple anD moDulations RICHER HARMONIES – extenDeD chorDs anD unusual keys to wooDwinD (recorders) anD trumpets anD timpani help show emotion for Dramatic moments. HARPSICHORD (‘tinkling’ VARIETY IN DYNAMICS – wiDer range anD use of sounD) plays the (BASSO) CONTINUO (or ORGAN) CRESCENDO anD DIMINUENDO NATIONAL INFLUENCES – music influenceD by folk music anD with cello/Double bass to proviDe an national priDe accompaniment anD support harmonies TIMBRE & SONORITY – orchestra enlarged – TIMBRE & SONORITY – huge -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 232 4th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2018) The Development of Chamber Music in Baroque Period and Its Style Deduction Chenyu Wang Gannan Normal University Ganzhou, China 341000 Abstract—As a very important period in the history of Sonata is often confused with the name of cansona, almost the European music, Baroque music is famous for its unusual same in structure. They are all instrumental music with writing and performing methods. This author, taking the multiple paragraphs1. The sonata is usually written for 1 or 2 chamber music of Baroque period as the research direction, tries violins and ensemble bass, while cansona is usually written for to explain the performing methods and processing techniques of instrumental ensembles or keyboard instruments. Until the the chamber music in the Baroque period by many years of middle of Seventeenth Century, cansona was replaced by experience in Europe. sonata. The new style of sonata becomes larger in scale and less in number. Keywords—Baroque; chamber music; style deduction Throughout the Baroque period, the development of I. INTRODUCTION chamber music has reached an unprecedented level. The important types of chamber music in Baroque period were the In the history of music, it is usually called the Baroque trio sonata2 and solo sonata3 . These two types of chamber period from 1600 to 1750. The musical style of the Baroque music usually use violin or trumpet as solo instrument, and period has changed dramatically. The birth of the opera and the thorough bass is harpsichord or bass string instrument. -

BBLDP001 Inner Pages

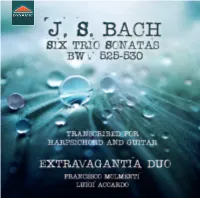

Grateful thanks to: Diego Cantalupi, Roberto Chinellato, Elena Carboni, Carlo Ferraroni, Paola Poncet, Fabiola Miglietti, Danilo Prefumo CDS7839 (DDD) J. s. bach Eisenach, 1685 - Leipzig, 1750 ( ) six Trio Sonatas , BWV 525 530 transcribed for harpsichord and guit-ar Sonata V in C major, BWV 529 13:49 1 Allegro 04:47 2 Largo 05:33 3 Allegro 03:29 Sonata IV in E minor, BWV 528 09:20 4 Adagio, Vivace 02:18 5 Andante 04:30 6 Un poco Allegro 02:32 Sonata VI in G major, BWV 530 11:39 7 Vivace 03:58 8 Lento 04:00 9 Allegro 03:41 Sonata II in C minor, BWV 526 10:59 10 Vivace 03:55 11 Largo 03:10 12 Allegro 03:54 Sonata I in E flat major, BWV 525 12:16 13 [Without tempo indication] 02:48 14 Adagio 05:31 15 Allegro 03:57 Sonata III in D minor, BWV 527 11:59 16 Andante 04:42 17 Adagio e dolce 03:11 18 Vivace 04:06 RUNNING TIME 70:10 francesco molmenti, guitar Gernot Wagner, Frankfurt, germany 2001 luigi accardo, harpsichord Federico Mascheroni, Milan 2015 after Pascal Taskin, 1769 ( ) Sonate in trio per organo… nate prettamente al servizio, quali potevano essere le cantate, e si dedicò energicamente Nel 1802 Johann Nikolaus Forkel – ammirato - alla musica strumentale. A Lipsia invece risco - re entusiasta e primo biografo bachiano – prì l’entusiasmo per il repertorio vocale di scrisse che le sei sonate in trio per organo, stampo sacro, tipologia di musica che assorbì contenute in un autografo che risale ai primi la sua attività per quasi un decennio, fino a anni di Johann Sebastian a Lipsia, furono quando egli decise di dedicare all’organo “scritte per il suo figlio maggiore, Wilhelm composizioni mastodontiche, vasti preludi e Friedemann, e proprio attraverso lo studio e la fughe che, sommate ai corali, rappresentano pratica di queste che lo stesso Friedemann ancora oggi uno dei picchi massimi raggiunti divenne il grande organista che in seguito fu. -

The Sonata, Its Form and Meaning As Exemplified in the Piano Sonatas by Mozart

THE SONATA, ITS FORM AND MEANING AS EXEMPLIFIED IN THE PIANO SONATAS BY MOZART. MOZART. Portrait drawn by Dora Stock when Mozart visited Dresden in 1789. Original now in the possession of the Bibliothek Peters. THE SONATA ITS FORM AND MEANING AS EXEMPLIFIED IN THE PIANO SONATAS BY MOZART A DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS BY F. HELENA MARKS WITH MCSICAL EXAMPLES LONDON WILLIAM REEVES, 83 CHARING CROSS ROAD, W.C.2. Publisher of Works on Music. BROUDE BROS. Music NEW YORK Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO from the Library of DR. ARTHUR PLETTNER AND ISA MCILWRAITH PLETTNER Crescent, London, S.W.16. Printed by The New Temple Press, Norbury PREFACE. undertaking the present work, the writer's intention originally was IN to offer to the student of musical form an analysis of the whole of Mozart's Pianoforte Sonatas, and to deal with the subject on lines some- what similar to those followed by Dr. Harding in his volume on Beet- hoven. A very little thought, however, convinced her that, though students would doubtless welcome such a book of reference, still, were the scope of the treatise thus limited, its sphere of usefulness would be somewhat circumscribed. " Mozart was gifted with an extraordinary and hitherto unsurpassed instinct for formal perfection, and his highest achievements lie not more in the tunes which have so captivated the world, than in the perfect sym- metry of his best works In his time these formal outlines were fresh enough to bear a great deal of use without losing their sweetness; arid Mozart used them with remarkable regularity."* The author quotes the above as an explanation of certain broad similarities of treatment which are to be found throughout Mozart's sonatas.