LIVRET RIC 425 DOWLAND 21X28 WEB.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Ruvo Irene De Ruvo

GIOVANNI BATTISTA DALLA GOSTENA GENUS CROMATICUM ORGAN WORKS, 1599 GIOVANNI BATTISTA DALLA GOSTENA GENUS CROMATICUM ORGAN WORKS, 1599 IRENE DE RUVO IRENE DE RUVO TRACKLIST P. 2 GIOVANNI BATTISTA DALLA GOSTENA ITA P. 4 GIOVANNI BATTISTA DALLA GOSTENA ENG P. 9 TRACKLIST P. 2 GIOVANNI BATTISTA DALLA GOSTENA ITA P. 4 GIOVANNI BATTISTA DALLA GOSTENA ENG P. 9 2 Menu Giovanni Battista Dalla Gostena (1558?-1593) AD 102 Genus Cromaticum Organ Works, 1599 01 Fantasia XII 5’59 02 Fantasia VII 4’01 03 Fantasia XXIII 2’23 04 Susane un jour (Orlando di Lasso) 6’07 05 Fantasia XXV 2’05 06 Fantasia IV 3’38 07 Fantasia IX 3’28 08 Mais que sert la richesse a l’homme (Guillaume Costeley) 3’37 09 Fantasia XXIV 3’04 10 Fantasia XIX 3’30 11 Fantasia VIII 4’50 12 Fantasia I 4’12 13 Fantasia XVI 2’25 14 Fantasia XIII 2’22 15 Fantasia V 3’43 16 Fantasia XVII 4’36 17 Pis ne me peult venir (Thomas Crecquillon) 3’46 18 Fantasia III 3’15 19 Fantasia XV 4’17 20 Fantasia XIV 3’13 21 Fantasia XXII 3’05 Total time 77’47 3 Menu Irene De Ruvo www.irenederuvo.com Graziadio Antegnati Organ, 1565 (Mantova, Basilica di Santa Barbara) Stoplist / Disposizione fonica Principale 16’ Fiffaro 16’ da fa2 Ottava 8’ Decima quinta 4’ Decima nona 2’ 2/3 Vigesima seconda 2’ Vigesima sesta 1 1/3 Vigesima nona 1’ Trigesima terza 2/3’ Trigesima sesta 1/2’ Flauto in XIX 2’ 2/3 Flauto in VIII 8’ Source: Intavolatura di liuto di Simone Molinaro Genovese, Libro Primo, Venezia 1599 Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze (S.P.E.S. -

Dowland's Grand Tour

Pegasus Early Music and NYS Baroque present Dowland’s Grand Tour Lute Music from England, France, Germany and Italy Paul O’Dette - lute Branle Anonymous Courante Volte Branle - Branle gay Branle Canaries (from Jean-Baptiste Besard, Thesaurus Harmonicus, Cologne 1603) Omnino Galliard John Johnson A Pavan to Delight (d. 1594) A Galliard to Delight Carman's Whistle Pavin Moritz, Landgrave of Hesse (1572 - 1632) Fantasia Gregorius Huwet (1560-1615) Fantasia nona (1599) Simone Molinaro Ballo detto il Conte Orlando (c. 1570-1636) Saltarello del predetto ballo Fantasia ottava La mia Barbara John Dowland A Galliard (30) (1563-1626) A Fancy (6) Paul O'Dette has been described as “the clearest case of genius ever to touch his instrument.” (Toronto Globe and Mail) One of the most influential figures in his field, O'Dette has helped define the technical and stylistic standards to which twenty-first-century performers of early music aspire. In doing so, he helped infuse the performance practice movement with a perfect combination of historical awareness, idiomatic accuracy, and ambitious self-expression. His performances at the major international festivals in Boston, Vienna, London, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, Munich, Prague, Milan, Florence, Geneva, Madrid, Barcelona, Tokyo, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Melbourne, Adelaide, Los Angeles, Vancouver, Berkeley, Bath, Montpellier, Utrecht, Bruges, Antwerp, Bremen, Dresden, Innsbruck, Tenerife, Copenhagen, Oslo, Cordoba, etc. have often been singled out as the highlight of those events. Paul O'Dette is Professor of Lute and Director of Early Music at the Eastman School of Music and Artistic Co-Director of the Boston Early Music Festival. -

Molinaro Danze E Fantasie Da Intavolatura Di Liuto Libro I Venezia 1599

95401 Molinaro Danze e Fantasie da Intavolatura di Liuto Libro I Venezia 1599 Ugo Nastrucci lute Simone Molinaro (c.1565-1636) Interest in the life and works of Simone Molinaro owes much to the music Danze e Fantasie da Intavolatura di Liuto Libro I, Venezia 1599 historiography that developed in Genoa during the second half of the 1800s, considerably in advance of similar developments elsewhere in Italy. During this period a number of brilliant minds, including archaeologists, historians and music lovers, set 1. Fantasia prima 1’55 10. Fantasia terza 2’27 to work on gathering musical documents and other non musical evidence regarding 2. Pass’e mezo in otto modi 5’26 11. Pass’e mezo in quattro modi 13’40 what was later recognized as being a proper school of music that evolved in the city 3. Gagliarda in quattro modi 1’43 12. Gagliarda in tre modi 3’09 between the mid 1500s and the first half of the following century: a musical reality 4. Saltarello primo 1’31 13. Fantasia sesta 3’13 that had such distinctive features as to warrant the epithet “Genoese style”. 5. Fantasia Undecima 2’42 14. Vng gaij bergier. Canzone Francese Still extremely valuable, those original studies concerning renaissance and baroque 6. Pass’e mezo in dieci modi 10’11 a quattro di Thomas Crecquillon. music in Genoa continued through to the 1920s, but by the post-war years had 7. Gagliarda in sei modi 2’08 Intavolata dal Molinaro come to a halt. The stagnation lasted for several decades, and it was only in the 8. -

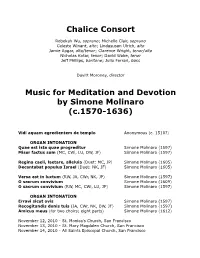

Chalice Consort Music for Meditation and Devotion

Chalice Consort Rebekah Wu, soprano; Michelle Clair, soprano Celeste Winant, alto; Lindasusan Ulrich, alto Jamie Apgar, alto/tenor; Clarence Wright, tenor/alto Nicholas Kotar, tenor; David Wake, tenor Jeff Phillips, baritone; Julio Ferrari, bass Davitt Moroney, director Music for Meditation and Devotion by Simone Molinaro (c.1570-1636) Vidi aquam egredientem de templo Anonymous (c. 1510?) ORGAN INTONATION Quae est ista quae progreditur Simone Molinaro (1597) Miser factus sum (MC, CWi, LU, DW, JF) Simone Molinaro (1597) Regina caeli, laetare, alleluia (Duet: MC, JP) Simone Molinaro (1605) Decantabat populus Israel (Duet: NK, JF) Simone Molinaro (1605) Versa est in luctum (RW, JA, CWr, NK, JP) Simone Molinaro (1597) O sacrum convivium Simone Molinaro (1609) O sacrum convivium (RW, MC, CWi, LU, JP) Simone Molinaro (1597) ORGAN INTONATION Erravi sicut ovis Simone Molinaro (1597) Recogitandis donis tuis (JA, CWr, NK, DW, JF) Simone Molinaro (1597) Amicus meus (for two choirs; eight parts) Simone Molinaro (1612) November 12, 2010 - St. Monica’s Church, San Francisco November 13, 2010 - St. Mary Magdalen Church, San Francisco November 14, 2010 - All Saints Episcopal Church, San Francisco Texts Vidi aquam (c.1510?) [Responsory, Intonation:] Vidi aquam [Responsory:] I saw water [Choir] egredientem de templo, coming forth from the temple a latere dextro, alleluia. on the right side, alleluia. E omnes, ad quos pervenit And all those to whom this aqua ist, salvi facti sunt. Alleluia. water came were saved. Alleluia. [Verse:] Confitemini Domino quoniam bonus: [Verse:] Praise the Lord, for He is good: Quoniam in saeculum Misericordia eius. For his mercy endureth forever. Gloria Patri, et Filio, Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, et Spiritui Sancto: and to the Holy Spirit: Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, As it was in the beginning, is now, et semper, et in saecula saeculorum. -

Italian Musical Culture and Terminology in the Third Volume of Michael Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum (1619)

Prejeto / received: 3. 6. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.04 ITALIAN MUSICAL CULTURE AND TERMINOLOGY IN THE THIRD VOLUME OF MICHAEL PRAETORIUs’S SYNTAGMA MUSICUM (1619) Marina Toffetti Università degli Studi di Padova Izvleček: Bralec tretjega zvezka Syntagme mu- Abstract: From the third volume of Michael sicum Michaela Praetoriusa dobi vtis, da so bili Praetorius’s Syntagma musicum one receives po mnenju avtorja na tekočem le tisti glasbeniki, the impression that, according to its author, ki so znali skladati, igrati ali peti »all'italiana«, only those who were able to compose, play or torej na italijanski način. Zato to delo predstavlja sing ‘all’italiana’ (in the Italian manner) were nekakšno ogledalo miselnosti in razumevanja considered culturally up-to-date. This treatise načina recepcije italijanske glasbe severno od can therefore be seen as a mirror reflecting Alp v drugem desetletju 17. stoletja. Razprava, ki the way in which Italian music was perceived temelji na ponovnem branju tretje knjige Prae- north of the Alps in the second decade of the toriusovega traktata Syntagma musicum, govori seventeenth century. The present article, based o tem, kako so v prvih desetletjih 17. stoletja on a re-reading of the third volume of Syntagma krožile glasbene knjige ter kako je asimilacija musicum, shows how in the early decades of italijanske glasbene kulture in terminologije the seventeenth century the circulation and prežela nemško govoreče dežele in doprinesla the assimilation of Italian musical culture and h genezi panevropskega glasbenega sloga in terminology was far-reaching in the German- terminologije. speaking countries, contributing to the genesis of a pan-European musical style and terminology. -

Participants' Abstracts and Biographies (In Alphabetical Order)

Mapping the post-Tridentine motet (ca. 1560-ca. 1610): Text, style and performance The University of Nottingham, 17-19 April 2015 Participants' abstracts and biographies (in alphabetical order) Todd Borgerding (Colby College, USA): Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John sing a motet The counterreformation saw an explosion of literature directed at developing and improving the art of preaching in the Catholic Church. These books—sacred rhetorics, sermons and homilies, 'preachable discourses', exegetical works, and the like—often make reference to music, and sometimes specifically to motets. Their authors, usually noted preachers, write about music in several ways: in discussions about the power of music (typically references to the classics or scripture), descriptions of angelic choirs making music, and, of particular interest, in allegorical or metaphorical reference to the sorts of choirs they knew from their own experience—that is, choirs made up of humans, either living or historical. This paper examines the writings of several of these authors, including Melchior de Huélamo’s Discorsos predicables sobre la Salve Regina (1601) and Juan Bautista de Madrigal’s Discursos predicables de las Domincas de Adviento y Fiestas de Santos hasta la Quaresma (1605), in which these discussions focus on the motet. These authors use the allegory of the choir of Evangelists, with the Holy Spirit as maestro de capilla, creating and singing a motet, in order to explain how scriptural texts are interdependent on each other. By reversing their analogy, we can better see how early modern preachers, and by extension, listeners to the counterreformation motet, understood this music as an inter- textual complex of word, counterpoint, and meaning. -

Espone Le Cose Sue Partite a Tutti

Prejeto / received: 28. 6. 2018. Odobreno / accepted: 20. 9. 2018 DOI: 10.3986/dmd14.1.04 “ESPONE LE COSE SUE PARTITE A TUTTI PER INDURLI ALLA MERAVIGLIA DELL’ARTE SUA” CONSIDERAZIONI SULLE PARTITURE DI MUSICA POLIFONICA IN ITALIA FINO ALL’EDIZIONE MOLINARO DEI MADRIGALI DI GESUALDO (1613) DINKO FABRIS Università degli Studi della Basilicata, Matera Izvleček: Prispevek povzema dosedanje raz- Abstract: The article summarizes the state of iskave zgodnjih italijanskih partitur do leta research on early Italian scores up to 1615, de- 1615. Ob tem je podana hipoteza o posebni veloping the hypothesis of a specific connection povezavi med dvema eminentnima lutnjistoma, between two eminent lutenists, Carlo Gesualdo Carlom Gesualdom in Simonejem Molinarom. and Simone Molinaro. The latter published in Slednji je leta 1613 v partiturnem zapisu izdal 1613 in score the six books of Gesualdo’s Madri- šest knjig Gesualdovih madrigalov in dve leti gals and two years later his own (only recently kasneje še (nedavno odkrito) lastno zbirko z discovered) Madrigali a cinque voci con parti- naslovom Madrigali a cinque voci con partitura. tura. Lute tablature could be considered a kind Lutenjsko tabulaturo bi lahko smatrali kot neke of score in which the vertical alignment of the vrste partituro, kjer je vertikalna poravnava polyphonic lines is fundamental not only when polifonih linij temeljnega pomena ne samo pri transcribing vocal music but also in composing transkribiranju vokalne glasbe, temveč tudi pri for the instrument. skladanju za instrument. Ključne besede: partitura, Gesualdo, Molinaro, Keywords: score, Gesualdo, Molinaro, notation, notacija, lutenjska tabulatura, Italija, zgodnje lute tablature, Italy, early seventeenth century 17. -

Modality and Chromaticism in the Madrigals of Don Carlo Gesualdo

Modality and Chromaticism in the Madrigals of Don Carlo Gesualdo Volume I of II Joseph Ian Knowles PhD Music University of York February 2014 2 Abstract Don Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, (1566–1613) is celebrated for his idiosyncratic use of chromaticism. Yet, the harmony of Gesualdo's madrigals evades modal rules and his chromatic style has perplexed analysts. This thesis reappraises the modal and chromatic features in his madrigals and expands on their significance by employing pitch-class set theory analysis to enhance a more traditional modal approach. Whilst analysis of the music through modal features and pitch-class set theory may appear to use contradictory analytical methods, the two can complement each other through the recognition of certain interval patterns regarded as significant by cinquecento music theorists. Ultimately, this analytical technique provides a language with which to articulate the modal and chromatic processes occurring in his music. In order to consolidate the results of the analyses, elements of compositional process are delineated and explored in the dissection of the madrigal '"Io parto" e non più dissi.' 3 4 Table of Contents Volume I Abstract ................................................................................................................... 3 List of Musical Examples in Volume I .................................................................... 10 List of Tables in Volume I ...................................................................................... 13 List of Accompanying -

Spring 2020 Classics & Jazz

1/800/222-6872 page 52 page 38 page 11 Spring 2020 Love Music. HBDirect Classics & Jazz HBDirect is pleased to present our Spring 2020 Clas- Spring 2020 sics & Jazz Catalog! As always, we offer an extensive selection of new Catalog Index J.S. Bach: Complete Cantatas / Ton Koopman [67 CDs] classical releases on both CD and video, as well as six 4 Classical - Recommendations Newly available, a reissued edition of the Complete Bach pages of recommendations and four of bestselling videos. 10 Classical - Best Selling Videos Cantatas, performed by Baroque music specialist Ton Browse new releases by time period and look to special Koopman and the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir, sections in this issue of new Harpsichord, Guitar & Lute, 14 Classical - New Releases with 67 CDs in carton sleeves. Ton Koopman is not only one Piano, Organ, Chamber Music, Choral, Strings, Broadway 46 Classical - DVD & Blu-ray of the great fathers of the Baroque-Renaissance revival in and Film Scores. This catalog includes six pages of jazz the 1970s, but a true pioneer of our time. After completing and another two pages of Blues, a genre that has recently 48 Blues - Classic Blues the Bach Cantatas survey, was he awarded the Bach Prize been added to the Classics & Jazz catalogs. Look out in 50 Jazz - Enlightenment Box Sets 2014 by the Royal Academy of Music. The prize is awarded to outstanding the coming weeks for a new Mixed-Genre catalog and visit 52 Jazz - Classics from Acrobat individuals in the performance and scholarship of Bach’s music. 67CD# CHL 72826 $389.99 HBDirect.com to see the full extent of what you can order.