Seven Lessons from Seven Continents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trip Hazzard 1.7 Contents

Trip Hazzard 1.7 Contents Contents............................................ 1 I Got You (I Feel Good) ................... 18 Dakota .............................................. 2 Venus .............................................. 19 Human .............................................. 3 Ooh La La ....................................... 20 Inside Out .......................................... 4 Boot Scootin Boogie ........................ 21 Have A Nice Day ............................... 5 Redneck Woman ............................. 22 One Way or Another .......................... 6 Trashy Women ................................ 23 Sunday Girl ....................................... 7 Sweet Dreams (are made of this) .... 24 Shakin All Over ................................. 8 Strict Machine.................................. 25 Tainted Love ..................................... 9 Hanging on the Telephone .............. 26 Under the Moon of Love ...................10 Denis ............................................... 27 Mr Rock N Roll .................................11 Stupid Girl ....................................... 28 If You Were A Sailboat .....................12 Molly's Chambers ............................ 29 Thinking Out Loud ............................13 Sharp Dressed Man ......................... 30 Run ..................................................14 Fire .................................................. 31 Play that funky music white boy ........15 Mustang Sally .................................. 32 Maneater -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

Music for Guitar

So Long Marianne Leonard Cohen A Bm Come over to the window, my little darling D A Your letters they all say that you're beside me now I'd like to try to read your palm then why do I feel so alone G D I'm standing on a ledge and your fine spider web I used to think I was some sort of gypsy boy is fastening my ankle to a stone F#m E E4 E E7 before I let you take me home [Chorus] For now I need your hidden love A I'm cold as a new razor blade Now so long, Marianne, You left when I told you I was curious F#m I never said that I was brave It's time that we began E E4 E E7 [Chorus] to laugh and cry E E4 E E7 Oh, you are really such a pretty one and cry and laugh I see you've gone and changed your name again A A4 A And just when I climbed this whole mountainside about it all again to wash my eyelids in the rain [Chorus] Well you know that I love to live with you but you make me forget so very much Oh, your eyes, well, I forget your eyes I forget to pray for the angels your body's at home in every sea and then the angels forget to pray for us How come you gave away your news to everyone that you said was a secret to me [Chorus] We met when we were almost young deep in the green lilac park You held on to me like I was a crucifix as we went kneeling through the dark [Chorus] Stronger Kelly Clarkson Intro: Em C G D Em C G D Em C You heard that I was starting over with someone new You know the bed feels warmer Em C G D G D But told you I was moving on over you Sleeping here alone Em Em C You didn't think that I'd come back You know I dream in colour -

Issue 3 April 2006

X Volume 6, Issue 3 April 2006 to suck. Or you don’t rock. We get that all the time. “Oh you guys were way better than I thought you were going to be”. Well, why ? Because we have breasts. I wanted to ask you about the name PANTYCHRIST. Where did that come from and what is the significance of the name ? Did it come in anyway from the band CONDO-CHRIST because there was a band from London called CONDO-CHRIST ? P: No. We didn’t even know that. D: CONDOM CHRIST ? No CONDO-CHRIST. P: This guy from another band had been watching us jam and we were tossing around names and we couldn’t come up with anything and he named us. We didn’t even know but there is another PANTY CHRIST. Some cross- dressing Japanese sampling guy who e-mailed us and said “Cool, use my name”. That’s okay. So that was cool. That is good. D: It’s because Izabelle looks really good in underwear. When we first started playing she PANTYCHRIST (FROM LEFT TO RIGHT): Amy with her back to us, Danyell on vocals, and Izabelle used to wear her underwear on stage. It was on guitar. Bob the Builder underwear. A couple of times in a row. You must have had those on for a PANTYCHRIST are a 4-piece punk band from while. No just joking (laughter). the steel capital of Canada. At the time of this What is the scene like in Hamilton ? From interview the band had released an 8-song our perspective it seems like a pretty thriving demo, a self-released ep, and were about to scene. -

A Substantive Theory on the Value of Group Music Therapy for Supporting Grieving Teenagers

Qualitative Inquiries in Music Therapy 2010: Volume 5, pp. 1–42 Barcelona Publishers TIPPING THE SCALES: A SUBSTANTIVE THEORY ON THE VALUE OF GROUP MUSIC THERAPY FOR SUPPORTING GRIEVING TEENAGERS Katrina McFerran1 ABSTRACT The value of group music therapy for bereaved young people has been described in a number of studies using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. This article details a qualitative investigation of a school-based program in Australia and presents the results of a grounded theory analysis of focus-group interviews conducted with adolescents. A brief empirical theory is presented in combination with a set of relational statements which conceptualize the phenomenon. This theory states that bereaved teenagers feel bet- ter if they have opportunities for fun and creative expression of their grief alongside their peers. This statement is compared to findings in the literature and addresses clinically re- levant issues of: how music therapy engages young people; what active music making means in this context; what constitutes the action of ―letting your feelings out‖; how the group influences the outcomes of its members; and how important a specific bereavement group is compared to a group with a broader ―loss and grief‖ focus. INTRODUCTION: SITUATING THE RESEARCH The research project described in this paper emerged from my clinical experience work- ing with young people whose parents or siblings had died of cancer while supported by a community based palliative care program. Music therapy became fundamental to the pro- vision of support for these young people because of the creative and non-verbal oppor- tunities that were available through it. -

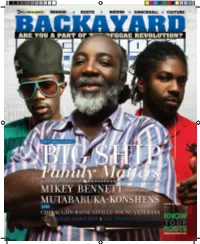

Untitled Will Be out in Di Near Near Future Tracks on the Matisyahu Album, I Did Something with Like Inna Week Time

BACKAYARD DEEM TEaM Chief Editor Amilcar Lewis Creative/Art Director Noel-Andrew Bennett Managing Editor Madeleine Moulton (US) Production Managers Clayton James (US) Noel Sutherland Contributing Editors Jim Sewastynowicz (US) Phillip Lobban 3G Editor Matt Sarrel Designer/Photo Advisor Andre Morgan (JA) Fashion Editor Cheridah Ashley (JA) Assistant Fashion Editor Serchen Morris Stylist Judy Bennett Florida Correspondents Sanjay Scott Leroy Whilby, Noel Sutherland Contributing Photographers Tone, Andre Morgan, Pam Fraser Contributing Writers MusicPhill, Headline Entertainment, Jim Sewastynowicz, Matt Sarrel Caribbean Ad Sales Audrey Lewis US Ad Sales EL US Promotions Anna Sumilat Madsol-Desar Distribution Novelty Manufacturing OJ36 Records, LMH Ltd. PR Director Audrey Lewis (JA) Online Sean Bennett (Webmaster) [email protected] [email protected] JAMAICA 9C, 67 Constant Spring Rd. Kingston 10, Jamaica W.I. (876)384-4078;(876)364-1398;fax(876)960-6445 email: [email protected] UNITED STATES Brooklyn, NY, 11236, USA e-mail: [email protected] YEAH I SAID IT LOST AND FOUND It seems that every time our country makes one positive step forward, we take a million negative steps backward (and for a country with about three million people living in it, that's a lot of steps we are all taking). International media and the millions of eyes around the world don't care if it's just that one bad apple. We are all being judged by the actions of a handful of individuals, whether it's the politician trying to hide his/her indiscretions, to the hustler that harasses the visitors to our shores. It all affects our future. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

HUG Songbook Volume 1 & 2 a Collection of Songs Used by the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

THE COMPENDIUM OF AWESOME! THE COMPLETE VOLUME 1 & 2 REVISED JANUARY 2016 The HUG Songbook Volume 1 & 2 A collection of songs used by the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada All of the songs contained within this book are for research and personal use only. Many of the songs have been simplified for playing at our club meetings. General Notes: ¶ The goal in assembling this songbook was to pull together the bits and pieces of music used at the monthy gatherings of the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) ¶ Efforts have been made to make this document as accurate as possible. If you notice any errors, please contact us at http://halifaxukulelegang.wordpress.com/ ¶ The layout of these pages was approached with the goal to make the text as large as possible while still fitting the entire song on one page ¶ Songs have been formatted using the ChordPro Format: The Chordpro-Format is used for the notation of Chords in plain ASCII-Text format. The chords are written in square brackets [ ] at the position in the song-text where they are played: [Em] Hello, [Dm] why not try the [Em] ChordPro for[Am]mat ¶ Many websites and music collections were used in assembling this songbook. In particular, many songs in this volume were used from https://ukutabs.com/, Richard G’s Ukulele Songbook (http://www.scorpex.net/uke.htm), the Bytown Ukulele Group website (http://www.bytownukulele.ca/) and the BURP (Berkhamsted Ukulele Random Players) website (http://www.hamishcurrie.me.uk/burp/index.htm). ¶ Ukulizer (http://www.ukulizer.com/) was used to transpose many songs into ChordPro format. -

2017 Songbooks (Autosaved).Xlsx

Song Title Artist Code 1 Mortin Solveig & Same White 21412 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 20606 1999 Prince 20517 #9 dream John Lennon 8417 1 + 1 Beyonce 9298 1 2 3 One Two Three Len Barry 4616 1 2 step Missy Elliot 7538 1 Thing Amerie 20018 1, 2 Step Ciara ft. Missy Elliott 20125 10 Million People Example 10203 100 Years Five For Fighting 4453 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 6117 1000 miles away Hoodoo Gurus 7921 1000 stars natalie bathing 8588 12:51 Strokes 4329 15 FEET OF SNOW Johnny Diesel 9015 17 Forever metro station 8699 18 and life skid row 7664 18 Till i die Bryan Adams 8065 1959 Lee Kernagan 9145 1973 James Blunt 8159 1983 Neon Trees 9216 2 Become 1 Jewel 4454 2 FACED LOUISE 8973 2 hearts Kylie Minogue 8206 20 good reasons thirsty merc 9696 21 Guns Greenday 8643 21 questions 50 Cent 9407 21st century breakdown Greenday 8718 21st century girl willow smith 9204 22 Taylor Swift 9933 22 (twenty-two) Lily Allen 8700 22 steps damien leith 8161 24K MAGIC BRUNO MARS 21533 3 (one two three) Britney Spears 8668 3 am Matchbox 20 3861 3 words cheryl cole f. will 8747 4 ever Veronicas 7494 4 Minutes Madonna & JT 8284 4,003,221 Tears From Now Judy Stone 20347 45 Shinedown 4330 48 Special Suzi Quattro 9756 4TH OF JULY SHOOTER JENNINGS 21195 5, 6, 7, 8. steps 8789 50 50 Lemar 20381 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Paul Simon 1805 50 ways to say Goodbye Train 9873 500 miles Proclaimers 7209 6 WORDS WRETCH 32 21068 7 11 BEYONCE 21041 7 Days Craig David 2704 7 things Miley Cyrus 8467 8675309 Jenny Tommy Tutone 1807 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 20210 99 Red Balloons Nena -

Travelin Songs

Travelin Songs A Collection of Imagined Historical Events by Janice Franklin Turner A creative project submitted to Sonoma State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in English Committee Members: Stefan Kiesbye Anne Goldman May 14, 2021 i Copyright 2021 By Janice Franklin Turner ii Authorization for Reproduction of Master’s Project Permission to reproduce this project in its entirety must be obtained from me. May 14, 2021 Janice Franklin Turner iii Travelin Songs A Collection of Imagined Historical Events Creative project by Janice Franklin Turner Abstract The history of the United States has been fraught with contradictions that challenge the meaning of the values we have always professed. Despite it all, Black and other minoritized people have persevered, making lives within the conditions that they have been forced to exist. Yet, there is little in historical documents that captures the laughter, joy and sorrow that creates the soul of a minoritized people. These tales are historically reimagined gazes into Black lives that portrays that which makes us all human. Through this collection, voice is given to what can’t be found in historical documents in an effort to bridge that gap. When we were growing up my mother always told us, “All that don’t kill you will make you strong.” I spent time thinking about the power that exist behind these words as I created the details for each of the stories in this collection. We never thought about Mama’s statement in the literal sense, thinking to do so was much too morbid. -

Recent Hits of the 2000S

This document will assist you with the right choices of music for your event; it contains examples of recent music. Song Artist Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj A Sky Full of Stars Coldplay This Is How We Do Katy Perry Klingande Jubel Only Love Can Hurt Like This Paloma Faith She Came to Give it to You Usher feat Nicki Minaj Addicted To You Avicii Amnesia 5 SOS Run Alone 360 XO Beyonce (Funk Mix) Best Day Of My Life American Authors Birthday Katy Perry Safe And Sound Capital Cities Boom Clap Charli XCX Shot Me Down David Guetta Bad David Guetta Ft Vassy I got You Duke Dumont Sing Ed Sherran Next To Me Emeli Sande Ugly Heart GRL Please Don’t Say You Love Me Gabrielle Aplin Budapest George Ezra The Wire HAIM Que Sera Justice Crew Fancy Iggy Azalea ft Charli XCX Hideaway Kiesza Turn Down For What DJ Snake & Lil Jon Faded ZHU Replay Zendaya 0402 277 208 | [email protected] | www.djdiggler.com.au | 21 Higgs Ct, Wynnum West, Queensland, Australia 4178 Waves Mr Probz High Peking Duk Summer Calvin Harris Birthday Katie Perry XO Beyoncé Addicted To You Avicii Braveheart Neon Jungle Love Runs Out One Republic my love route 94 - (feat. jess glynne) Free Rudimental - feat. Emeli Sandé Stay With Me Sam Smith Brave Sara Bareilles Geronimo Sheppard Chandelier Sia Rather Be Clean Bandit - feat. Jess Glynne I Got You Duke Dumont Sing Ed Sheeran Next To Me Emeli Sandé The Power of Love Gabrielle Aplin The Wire HAIM Que Sera Justice Crew Hideaway Kiesza Undressed Kim Cesarion Magic Coldplay Happy Pharrel Williams Riptide Vance Joy -

![KARAOKE - 2000 by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 553 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9704/karaoke-2000-by-artist-no-of-tunes-553-4729704.webp)

KARAOKE - 2000 by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 553 ]

[ KARAOKE - 2000 by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 553 ] 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {Karaoke} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {Karaoke} A T C >> MY HEART BEATS LIKE A DRUM {Karaoke} AALIYAH >> TRY AGAIN {Karaoke} AGNES >> RELEASE ME {Karaoke} AKON >> DON'T MATTER {Karaoke} ALCATRAZ >> CRYING AT THE DISCOTHEQUE {Karaoke} ALCAZAR >> DON'T YOU WANT ME {Karaoke} ALESHA DIXON >> THE BOY DOES NOTHING {Karaoke} ALEX LLOYD >> AMAZING {Karaoke} ALICE D J >> BACK IN MY LIFE {Karaoke} ALICE D J >> WILL I EVER {Karaoke} ALICIA KEYS >> NO ONE {Karaoke} ALIEN ANT FARM >> SMOOTH CRIMINAL {Karaoke} ALL AMERICAN REJECTS >> GIVES YOU HELL {Karaoke} AMANDA PEREZ >> ANGEL {Karaoke} AMERIE >> 1 THING {Karaoke} AMIEL >> LOVE SONG {Karaoke} ANASTACIA >> I'M OUTA LOVE {Karaoke} ANASTACIA >> LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE {Karaoke} ANASTACIA >> SICK AND TIRED {Karaoke} ANDROIDS >> DO IT WITH MADONNA {Karaoke} ANTHONY CALLEA >> ADDICTED TO YOU {Karaoke} ANTHONY CALLEA >> HURTS SO BAD {Karaoke} ANTHONY CALLEA >> RAIN {Karaoke} ANTHONY CALLEA >> THE PRAYER {Karaoke} AQUA >> AROUND THE WORLD {Karaoke} ASHANITI >> FOOLISH {Karaoke} ASHLEE SIMPSON >> BOYFRIEND {Karaoke} ASHLEE SIMPSON >> LA LA {Karaoke} ASHLEE SIMPSON >> LOVE {Karaoke} ASHLEE SIMPSON >> OUTTA MY HEAD {Karaoke} ASHLEE SIMPSON >> PIECES OF ME {Karaoke} ASHLEE SIMPSON >> SHADOW {Karaoke} ATOMIC KITTEN >> IT'S OK {Karaoke} ATOMIC KITTEN >> THE TIDE IS HIGH {Karaoke} ATOMIC KITTEN >> WHOLE AGAIN {Karaoke} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> COMPLICATED {Karaoke} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> DON'T TELL ME {Karaoke} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> GIRLFRIEND {Karaoke}