International Narcotics Control Strategy Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customs Act (Republic of Korea)

Customs Act (Republic of Korea) By Ministry of Legislation INTRODUCTION Details of Enactment and Amendment ● Enactment: The Customs Act was enacted in 1949, and after being amended over more than 35 occasions, wholly amended in the year of 2000, and then partly amended in the year of 2002. This Act provides not only the regulatory details on the imposition and collection of customs, but also the matters concerning the overall customs administrative details, such as the taxpayer's right and procedure for filing objections, bonded area, clearance procedures, and punishment of customs criminals, etc. ● Amendment: The recent amendments of the Customs Act have been made in the year of 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2002, and such amendments are meant to improve the bond systems in order to induce foreign investments, to simplify the appeal procedures against the imposition of customs, and to strengthen the guarantee of duty payer's right by enacting the Charter of Duty Payer's Rights. The grounds for TSG (Transitional Safeguard) against China are newly established according to the joining of China in WTO, the e-delivery system and the system of designation of e-document brokerage operator are newly introduced to implement e-government, and the requirements for the return of travelers' personal effects excessively carried in are strengthened to restrict indiscreet shipping-in of personal effects. Main Contents ● The customs are imposed in principle based on the time of import declaration, but their tax rates are separately stipulated in the Tariff Schedule: Provided, That the simple customs are imposed on personal effect, mail, and consignment. -

International Narcotics Control Strategy Report

United States Department of State Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs International Narcotics Control Strategy Report Volume I Drug and Chemical Control March 2017 INCSR 2017 Volume 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents Common Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. iii International Agreements .......................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Policy and Program Developments ......................................................................................................... 17 Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 18 Methodology for U.S. Government Estimates of Illegal Drug Production ............................................... 24 (with dates ratified/acceded) ................................................................................................................... 30 USG Assistance ..................................................................................................................................... 36 International Training ............................................................................................................................. -

Section 3 2018 Edition

S e c ti o n 3 Vessel Requirements 3.1 Definitions, p. 2 3.2 Size and Draft Limitations of Vessels, p. 4 3.3 Requirement for Pilot Platforms and Shelters on Certain Vessels, p. 16 3.4 Navigation Bridge Features Required of Transiting Vessels, p. 19 3.5 Requirements for Non-Self-Propelled Vessels, p. 31 3.6 Vessels Requiring Towing Services, p. 32 3.7 Deckload Cargo, p. 33 3.8 Construction, Number and Location of Chocks and Bitts, p. 34 3.9 Mooring Lines, Anchors and Deck Machinery, p. 41 3.10 Boarding Facilities, p. 41 3.11 Definite Phase-out of Single-Hull Oil Tankers, p. 47 3.12 Admeasurement System for Full Container Vessels, p. 48 3.13 Deck-loaded Containers on Ships not Built for Container Carriage, p. 49 3.14 Unauthorized Modification to the PC/UMS Net Tonnage Certificate, p. 50 3.15 Calculation of PC/UMS Net Tonnage on Passenger Vessels, p. 51 3.16 Dangerous Cargo Requirements, p. 51 3.17 Cargo Regulated Under MARPOL Annex II, p. 58 3.18 Pre-Arrival Cargo Declarations, Security Inspection and Escort, p. 58 3.19 Hot Work Performed On Board Vessels, p. 60 1 OP Operations Manual Section 3 2018 Edition 3.20 Manning Requirements, p. 61 3.21 Additional Pilots Due to Vessel Deficiencies, p. 62 3.22 Pilot Accommodations Aboard Transiting Vessels, p. 63 3.23 Main Source of Electric Power, p. 63 3.24 Emergency Source of Electrical Power, p. 63 3.25 Sanitary Facilities and Sewage Handling, p. -

Etodesnitazene

Etodesnitazene Sample Type: Biological Fluid Latest Revision: February 23, 2021 Date of Report: February 23, 2021 1. GENERAL INFORMATION IUPAC Name: 2-[2-[(4-ethoxyphenyl)methyl]benzimidazol-1-yl]-N,N-diethyl- ethanamine InChI String: InChI=1S/C22H29N3O/c1-4-24(5-2)15-16-25-21-10-8-7-9-20(21)23- 22(25)17-18-11-13-19(14-12-18)26-6-3/h7-14H,4-6,15-17H2,1-3H3 CFR: Not Scheduled (02/2021) CAS# Not available Synonyms: Etazene, Desnitroetonitazene, Etazen, Etazone Source: Oregon State Police Forensic Laboratory Important Notes: All identifications were made based on evaluation of analytical data (LC-QTOF-MS) in comparison to analysis of acquired reference material. This drug was also confirmed via LC-MS/MS. Prepared By: Janet Schultz, PhD; Sailee Raje; Sara Short, MS, D-ABFT-FT; Michele Stauffenberg, MD; Alex J. Krotulski, PhD; Melissa F. Fogarty, MSFS, D-ABFT-FT; and Barry K. Logan, PhD, F-ABFT 2. CHEMICAL DATA Chemical Molecular Molecular Exact Mass Analyte Formula Weight Ion [M+] [M+H]+ Etodesnitazene C22H29N3O 351.5 351 352.2383 3. SAMPLE HISTORY Etodesnitazene has been identified in one case since December 2020. The geographical and demographical breakdown is below: Geographical Location: Oregon (n=1) Biological Sample: Subclavian Blood (n=1) Date of First Receipt: December 2020 Other Notable Findings: Etizolam, Methamphetamine, Mitragynine 4. BRIEF DESCRIPTION Etodesnitazene is classified as a novel opioid of the benzimidazole sub-class and is structurally dissimilar from fentanyl. Novel opioids have been reported to cause psychoactive effects similar to heroin, fentanyl, and other opioids. -

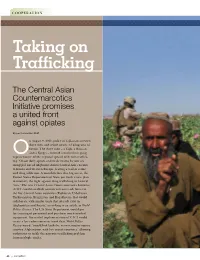

Taking on Trafficking

COOPEration Taking on Trafficking The Central Asian Counternarcotics Initiative promises a united front against opiates By per Concordiam Staff n August 9, 2011, police in Tajikistan arrested three men and seized nearly 32 kilograms of heroin. The three men – a Tajik, a russian and a Kyrgyz – formed a multiethnic gang Orepresentative of the regional spread of heroin traffick- ing. Almost daily, opium and its derivative heroin are smuggled out of Afghanistan into Central Asia en route to russia and Western Europe, leaving a trail of crime and drug addiction. A month before that big arrest, the United States Department of State put forth a new plan to intensify the fight against drug trafficking in Central Asia. “The new Central Asian Counternarcotics Initiative (CACI) would establish counternarcotics task forces in the five Central Asian countries (Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan) that would collaborate with similar units that already exist in Afghanistan and russia,” according to an article in World Politics Review. The U.S. State Department would pay for training of personnel and purchase much-needed equipment. Successful implementation of CACI would create a law enforcement network that, World Politics Review noted, “would link both the main narcotics source country, Afghanistan, with key transit countries,” allowing authorities to tackle the narcotics trafficking problem from multiple angles. 40 per Concordiam “According to a 2010 report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Afghanistan produces 85 percent of the world’s heroin, and almost one-fourth of that is exported through post-Soviet Central Asia.” A counternarcotics specialist embedded with the U.S. -

Investigation by the Office of Special Counsel

U.S. Department of Justice Dmg Enforcement Administration Office of the Administrator Springfield, VA 22152 April 5, 2019 MEMORANDUM FOR THE ATTORNEY GENERAL if.)1.-- THROUGH: THE DEPUTY ATTORNEY GENERAL ~,0. ~ c}:<i..li-\~ei1\' FROM: Uttam Dhillon( I) O Acting Administrator SUBJECT: Delegation of Authority PURPOSE: To obtain a delegation of authority pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 1213 in order provide response to request for investigation by the Office of Special Counsel TIMETABLE: Immediately DISCUSSION: By letter dated May 15, 2018, the Office of Special Counsel (OSC) has requested the Attorney General to investigate allegations from two Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) employees that DEA failed to assist Haitian law enforcement with implementing basic seaport security measures and failed to properly conduct its investigation into what was alleged to be the only significant drug seizure in Port-au-Prince in the past 10 years. Under 5 U.S.C. §1213(c) and (g), upon the receipt of such a referral, the agency head is required to conduct an investigation and prepare a report. Under 28 U.S.C. §510, and consistent with agency practice implementing 5 U.S.C. §1213, as recognized by the OSC, you may delegate the responsibilities under section 1213 to conduct an investigation and prepare the related report. This includes delegation of the authority to take actions as a result of the investigation pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 1213(d) (5). On May 22, 2018, the Department of Justice Executive Secretariat (ES) sent the OSC letter to DEA under ES Workflow ID number 4033252 "for appropriate handling." Based on the ES tasking, the DEA conducted the investigation and, on September 6, 2018, I signed a cover letter addressed to SA Counsel Hemy J. -

REPRESENTATIVES of PARTIES Superintendent W

Ms T. Spisbah First Secretary (Economic), Australian High Commission, New Delhi REPRESENTATIVES OF PARTIES Superintendent W. Moran Counsellor (Australian Border Force), Australian High Commission, New Delhi AFGHANISTAN AUSTRIA Chief delegate Chief delegate Dr F. Pietsch Dr B.A. Sarwari Director, Federal Ministry of Health and Women's Affairs Mental Health Director and Focal Point for FCTC Deputy chief delegate ALGERIA Mr G. Zehetner Chief delegate Minister Plenipotentiary, Embassy of Austria in New Delhi M. A. Boudiaf Minister of Health Delegate Dr H. Heller Delegate Director, Federal Ministry of Finance M. H. Yahia-Cherif Mr A. Weinseiss Ambassador of Algeria in New Delhi Advisor, Federal Ministry of Health and Women's Affairs M. M. Smail Mr C. Meyenburg Director General of Prevention and Health Promotion Minister Plenipotentiary, Embassy of Austria in New Delhi M. N. Zidouni President of the National Committee for prevention and BAHRAIN awareness on smoking Chief delegate M. M. Samet Minister-Counselor at the Embassy of Algeria in New Delhi Dr E. Alalawi Head, Antismoking Group. Focal Point of Tobacco Control M. S. Rahem Attache of Foreign Affairs at the Permanent Mission of Algeria in Geneva BANGLADESH Chief delegate ANGOLA Mr M.R. Quddus Coordinator, National Tobacco Control Cell and Joint Secretary, Chief delegate Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Dr M.F. Wilson Chocolate Manuel Coordinator of the Cabinet of Health Promotion Delegate Mr A.G. Khan ARMENIA Joint Secretary, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Chief delegate Mr S.M.A. Aziz Deputy Secretary, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Mr A. Martirosyan H.E. Ambassador of Republic of Armenia to India Dr. -

PHASE IV and the Vienna Declaration PARIS PACT PARTNERS

www.paris-pact.net >> PHASE IV and the Vienna Declaration PARIS PACT PARTNERS 58 PARIS PACT PARTNER COUNTRIES Afghanistan (Islamic Republic of) Denmark Latvia Serbia Albania Estonia Lithuania Slovakia Armenia Finland Luxembourg Slovenia Australia * France Macedonia (The former Yugoslav Spain Austria Georgia Republic of) Sweden Azerbaijan Germany Malta Switzerland Belarus Greece Moldova (Republic of) Tajikistan Belgium Hungary Montenegro Turkey Bosnia and Herzegovina India Netherlands Turkmenistan Bulgaria Iran (Islamic Republic of) Norway Ukraine Canada Ireland Pakistan (Islamic Republic of) United Arab Emirates * China (The People’s Republic of) * Italy Poland United Kingdom Croatia Japan Portugal United States of America Cyprus Kazakhstan Romania Uzbekistan Czech Republic Kyrgyzstan Russian Federation 23 PARIS PACT PARTNER ORGANIZATIONS • Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination • International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) Centre (CARICC) • Interpol (INTERPOL) • Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) • North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) • Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) • Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) • Council of Europe (CE) • Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) • Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) • Southeast European Law Enforcement Center (SELEC) • Eurasian Group on Combating Money Laundering and • United Nations Aids Programme (UNAIDS) Terrorist Financing (EAG) * • United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) • European Monitoring Centre for -

Communicationfile-132886.Pdf

From: Nazlee Maghsoudi To: Board of Health Cc: Werb, Daniel; Hayley Thompson; Karen McDonald Subject: BOH June 14, 2021 - CDPE Comments on HL29.2 Date: June 13, 2021 6:52:20 PM Attachments: 2021-06-14_CDPE Comments to BOH_Toronto Overdose Action Plan Status Report 2021.pdf To the Members of the Board of Health, Please find attached comments from the Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation (CDPE) regarding agenda item HL29.2 (Toronto Overdose Action Plan: Status Report 2021) to be considered at the Board of Health meeting on Monday, June 14. We would greatly appreciate if you could please confirm receipt. Thanks so much, Nazlee Maghsoudi, BComm, MGA Doctoral Candidate, Health Services Research | Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto Manager, Policy Impact Unit | Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation (CDPE) Chairperson, Executive Committee | New York NGO Committee on Drugs (NYNGOC) Strategic Advisor | Canadian Students for Sensible Drug Policy (CSSDP) (647) 702-7825 Pronouns: She/Her Submission from Nazlee Maghsoudi, Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation Toronto's Dru·g Checking Service Coordinated by the Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation > i" Comments for Board of Health Consideration of “Toronto Overdose Action Plan: Status Report 2021” June 14, 2021 What does Toronto’s drug checking service do? • Offers people who use drugs timely and detailed information on the contents of their drugs, helping them to make more informed decisions • Shares information on Toronto’s unregulated drug supply to help harm reduction workers and clinicians tailor the care they provide to people who use drugs • Advocates for services and safer alternatives for people who use drugs 2 Free and anonymous drug checking is now available! What you give .. -

2020 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report

United States Department of State Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs International Narcotics Control Strategy Report Volume I Drug and Chemical Control March 2020 INCSR 2020 Volume 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents Common Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................... iii International Agreements.................................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Legislative Basis for the INCSR ......................................................................................................................... 2 Presidential Determination ................................................................................................................................. 7 Policy and Program Developments .................................................................................................... 12 Overview ......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Methodology for U.S. Government Estimates of Illegal Drug Production .......................................................... 18 Parties to UN Conventions .............................................................................................................................. -

ONI-54-A.Pdf

r~us U. S. FLEET TRAIN- Division cf Naval Intelligence-Identification and Characteristics Section e AD Destroyer Tenders Page AP Troop Transports Pa g e t Wo "'W" i "~ p. 4-5 z MELVILLE 28 5 BURROWS 14 3, 4 DOBBIN Class 4 7 WHARTON 9 9 BLACK HAWK 28 21, 22 WAKEFIELD Class 12 11, 12 ALTAIR Class 28 23 WEST POINT 13 14, 15, 17-19 DIXIE Class 7 24 ORIZABA 13 16 CASCADE 10 29 U. S. GRANT 14 20,21 HAMUL Class 22 31, 3Z CHATEAU THIERRY Class 9 33 REPUBLIC 14 AS Submarine Tenders 41 STRATFORD 14 3 HOLLAND 5 54, 61 HERMIT AGE Class 13 5 BEAVER 16 63 ROCHAMBEAU 12 11, 12, 15 19 FULTON Class 7 67 DOROTHEA L. DIX 25 Sin a ll p. H 13, 14 GRIFFIN Class 22 69- 71,76 ELIZ . STANTON Cla ss 23 20 OTUS 26 72 SUSAN B. ANTHONY 15 21 AN TEA US 16 75 GEMINI 17 77 THURSTON 20 AR Repair Ships 110- "GENERAL" Class 10 1 MEDUSA 5 W orld W ar I types p. 9 3, 4 PROMETHEUS Class 28 APA Attack Transports 5- VULCAN Class 7 1, 11 DOYEN Class 30 e 9, 12 DELTA Class 22 2, 3, 12, 14- 17 HARRIS Class 9 10 ALCOR 14 4, 5 McCAWLEY , BARNETT 15 11 RIGEL 28 6-9 HEYWOOD Class 15 ARH Hull Repair Ships 10, 23 HARRY LEE Class 14 Maritime types p. 10-11 13 J T. DICKMAN 9 1 JASON 7 18-zo; 29, 30 PRESIDENT Class 10 21, 28, 31, 32 CRESCENT CITY Class 11 . -

Exposures Associated with Clandestine Methamphetamine Drug Laboratories in Australia

Rev Environ Health 2016; 31(3): 329–352 Jackie Wright*, John Edwards and Stewart Walker Exposures associated with clandestine methamphetamine drug laboratories in Australia DOI 10.1515/reveh-2016-0017 Received April 20, 2016; accepted June 7, 2016; previously published Introduction online July 18, 2016 Illicit drugs such as amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) Abstract: The clandestine manufacture of methamphet- (1) are manufactured in Australia within clandestine amine in residential homes may represent significant laboratories that range from crude, makeshift operations hazards and exposures not only to those involved in the using simple processes to sophisticated operations. These manufacture of the drugs but also to others living in the laboratories use a range of chemical precursors to manu- home (including children), neighbours and first respond- facture or “cook” ATS that include methylamphetamine, ers to the premises. These hazards are associated with more commonly referred to as methamphetamine (“ice”) the nature and improper storage and use of precursor and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or chemicals, intermediate chemicals and wastes, gases and “ecstasy”). In Australia the primary ATS manufactured methamphetamine residues generated during manufac- in clandestine drug laboratories is methamphetamine ture and the drugs themselves. Many of these compounds (2), which is the primary focus of this review. Clandes- are persistent and result in exposures inside a home not tine laboratories are commonly located within residential only during manufacture but after the laboratory has been homes, units, hotel rooms, backyard sheds and cars, with seized or removed. Hence new occupants of buildings for- increasing numbers detected in Australia each year (744 merly used to manufacture methamphetamine may be laboratories detected in 2013–2014) (2).