Rethinking Metal Aesthetics: Complexity, Authenticity, and Audience in Meshuggah’S I and Catch Thirtythr33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ho Li Day Se Asons and Va Ca Tions Fei Er Tag Und Be Triebs Fe Rien BEAR FAMILY Will Be on Christmas Ho Li Days from Vom 23

Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 12. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 12th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 12. Janu ar 2004 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken day 12th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - wir uns für die gute Zusam menar beit im ver gange nen mers for their co-opera ti on in 2003. It has been a Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY...............................2 BEAT, 60s/70s.........................66 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. ........................19 SURF ........................................73 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER ..................22 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY .......................75 WESTERN .....................................27 BRITISH R&R ...................................80 C&W SOUNDTRACKS............................28 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT ........................80 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS ......................28 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND ...............29 POP ......................................82 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE .................30 POP INSTRUMENTAL ............................90 -

The Meshuggah Quartet

The Meshuggah Quartet Applying Meshuggah's composition techniques to a quartet. Charley Rose jazz saxophone, MA Conservatorium van Amsterdam, 2013 Advisor: Derek Johnson Research coordinator: Walter van de Leur NON-PLAGIARISM STATEMENT I declare 1. that I understand that plagiarism refers to representing somebody else’s words or ideas as one’s own; 2. that apart from properly referenced quotations, the enclosed text and transcriptions are fully my own work and contain no plagiarism; 3. that I have used no other sources or resources than those clearly referenced in my text; 4. that I have not submitted my text previously for any other degree or course. Name: Rose Charley Place: Amsterdam Date: 25/02/2013 Signature: Acknowledgment I would like to thank Derek Johnson for his enriching lessons and all the incredibly precise material he provided to help this project forward. I would like to thank Matis Cudars, Pat Cleaver and Andris Buikis for their talent, their patience and enthusiasm throughout the elaboration of the quartet. Of course I would like to thank the family and particularly my mother and the group of the “Four” for their support. And last but not least, Iwould like to thank Walter van de Leur and the Conservatorium van Amsterdam for accepting this project as a master research and Open Office, open source productivity software suite available on line at http://www.openoffice.org/, with which has been conceived this research. Introduction . 1 1 Objectives and methodology . .2 2 Analysis of the transcriptions . .3 2.1 Complete analysis of Stengah . .3 2.1.1 Riffs . -

Progressive Traits in the Music of Dream Theater Thesis Written for the Bachelor of Musicology University of Utrecht Supervised by Professor Karl Kügle June 2013 1

2013 W. B. van Dijk 3196372 PROGRESSIVE TRAITS IN THE MUSIC OF DREAM THEATER THESIS WRITTEN FOR THE BACHELOR OF MUSICOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF UTRECHT SUPERVISED BY PROFESSOR KARL KÜGLE JUNE 2013 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Foreword .......................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 2: A definition of progressiveness ......................................................................................... 3 2.1 – Problematization ..................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 - A brief history of progressive rock ......................................................................................... 4 2.3 – Progressive rock in the classic age: 1968-1978 ...................................................................... 5 2.4 - A selective list of progressive traits ........................................................................................ 6 Chapter 3: Progressive Rock and Dream Theater ............................................................................... 9 3.1 – A short biography of the band Dream Theater ....................................................................... 9 3.2 - Progressive traits in Scenes from a Memory ......................................................................... 10 3.3 - Progressive traits in ‗The Dance of Eternity‘ ........................................................................ 12 Chapter 4: Discussion & -

Historical Development, Sound Aesthetics and Production Techniques of Metal’S Distorted Electric Guitar

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository Historical development, sound aesthetics and production techniques of metal’s distorted electric guitar Jan-Peter Herbst Abstract The sound of the distorted electric guitar is particularly important for many metal genres. It contributes to the music’s perception of heaviness, serves as a distinguishing marker, and is crucial for the power of productions. This article aims to extend the research on the distorted metal guitar and on metal music production by combining both fields of interest. By the means of isolated guitar tracks of original metal recordings, 10 tracks in each of the last five decades served as sample for a historical analysis of metal guitar aesthetics including the aspects tuning, loudness, layering and spectral composition. Building upon this insight, an experimental analysis of 287 guitar recordings explored the effectiveness and effect of metal guitar production techniques. The article attempts to provide an empirical ground of the acous- tics of metal guitar production in order to extend the still rare practice-based research and metal-ori- ented production manuals. Keywords: guitar, distortion, heaviness, production, history, aesthetics Introduction With the exception of genres like black metal that explicitly value low-fidelity aesthetics (Ha- gen 2011; Reyes 2013), the powerful effect of many metal genres is based on a high production quality. For achieving the desired heaviness, the sound of the distorted electric guitar is partic- ularly relevant (Mynett 2013). Although the guitar’s relevance as a sonic icon and its function as a distinguishing marker of metal’s genres have not changed in metal history (Walser 1993; Weinstein 2000; Berger and Fales 2005), the specific sound aesthetics of the guitar have varied substantially. -

Starset Vessels Download Mega

Starset vessels download mega Continue Posted in Discography | Tagged 2019, 2020, album, bajar, bso, free kancion, cd, completa, completo, descargar, disco, discrimination, discography, disco, download, free, mega, ost, runut sound, sus, todos 2021 Starset es una banda de rock estadouniensed formada por Dustin Bates, vocalist de ventaja Downplay Lanzaron me su primer álbum debut Transmission en 2014. Descarga: Download Download Song Starset Full Discography Album | MP3 / RAR / ZIP : Transmission (2014) Part (2017) Part (2019) Starset is an American rock group from Columbus, Ohio, founded by Dustin Bates in 2013. They released their first album, Transmissions, in 2014 and their second album, Vessels, on January 20, 2017. The group has found success in expanding their concept album ideas through social media and YouTube, with the band expanding, the band making more than $230,000 in revenue from the scene in November 2016. Their single Devil I has gained over 280 million views on YouTube in the same time period. Their most commercial song, Giant, peaked at number 2 on the U.S. Premiere Rock Chart in May 2017. The third studio album, Part, was released on September 13, 2014, and released on September 13, 2014. The band STARSET released their most successful first album Transmisi on July 8, 2014. It peaked at number 49 on the US Billboard 200 chart, making it one of the highest debut albums for a rock band in 2014, and in 2016, has sold over 79,000 copies. Three singles have been released in the Album promotion; My demons, Carnivores, and Hello. They also showed good performance in the charts, reaching fifth, sixteenth, and sixth on billboard's Best Rock Song chart. -

Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

HARMONIC RESOURCES IN 1980S HARD ROCK AND HEAVY METAL MUSIC A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Theory by Erin M. Vaughn December, 2015 Thesis written by Erin M. Vaughn B.M., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________ Richard O. Devore, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Director, School of Music _____________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER I........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................ 3 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................... 36 ANALYSIS OF “MASTER OF PUPPETS” ...................................................................................... -

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal *

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal * Stephen S. Hudson NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hudson.php KEYWORDS: Heavy Metal, Formenlehre, Form Perception, Embodied Cognition, Corpus Study, Musical Meaning, Genre ABSTRACT: This article presents a new framework for analyzing compound AABA form in heavy metal music, inspired by normative theories of form in the Formenlehre tradition. A corpus study shows that a particular riff-based version of compound AABA, with a specific style of buildup intro (Aas 2015) and other characteristic features, is normative in mainstream styles of the metal genre. Within this norm, individual artists have their own strategies (Meyer 1989) for manifesting compound AABA form. These strategies afford stylistic distinctions between bands, so that differences in form can be said to signify aesthetic posing or social positioning—a different kind of signification than the programmatic or semantic communication that has been the focus of most existing music theory research in areas like topic theory or musical semiotics. This article concludes with an exploration of how these different formal strategies embody different qualities of physical movement or feelings of motion, arguing that in making stylistic distinctions and identifying with a particular subgenre or style, we imagine that these distinct ways of moving correlate with (sub)genre rhetoric and the physical stances of imagined communities of fans (Anderson 1983, Hill 2016). Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory “Your favorite songs all sound the same — and that’s okay . -

Hammerfall One Crimson Night Mp3, Flac, Wma

HammerFall One Crimson Night mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: One Crimson Night Country: Germany Released: 2003 Style: Heavy Metal, Power Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1738 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1469 mb WMA version RAR size: 1229 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 276 Other Formats: DTS MMF MP4 AUD AC3 AAC AU Tracklist 1 Lore Of The Arcane 1:44 2 Riders Of The Storm 4:54 3 Heeding The Call 5:00 4 Stone Cold 7:10 5 Hero's Return 4:37 6 Legacy Of Kings 4:45 7 Bass Solo: Magnus Rosen 3:37 8 At The End Of The Rainbow 4:33 9 The Way Of The Warrior 4:03 10 The Unforgiving Blade 3:49 11 Glory To The Brave 6:35 12 Guitar Solo: Stefan Elmgren 2:43 13 Let The Hammer Fall 5:50 14 Renegade 3:54 15 Steel Meets Steel 4:37 16 Crimson Thunder 7:29 17 Templars Of Steel 6:10 18 Gold Album Award 19 Hearts On Fire 4:03 20 HammerFall 8:24 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Nuclear Blast Copyright (c) – Nuclear Blast Pressed By – Technicolor Recorded At – Lisebergshallen Mixed At – Studio Fredman Mastered At – Nilento Studio Credits A&R – Matthias Lasch Bass – Magnus Rosén Cover – Samwise Didier Drums, Photography By – Anders Johansson Guitar, Mixed By [Assistant], Photography By – Stefan Elmgren Guitar, Photography By – Oscar Dronjak Layout – Thomas Ewerhard Mastered By – Lars Nilsson Mixed By – Fredrik Nordström Other [Songs Published By] – Warner / Chappell And Prophecies Publishing Photography By – Michael Johansson , Per Stålfors, Sofia Nystedt Recorded By – Mikael Thieme Recorded By [Assistant] – Henke Henriksson Vocals, Photography By – Joacim Cans Notes Recorded live at Lisebergshallen, Göteborg, Sweden, on February 20th, 2003. -

Metal Guitar Sample Packs Free

Metal Guitar Sample Packs Free Yuri lites his Hindoos last fifty-fifty or slothfully after Lorenzo reactivate and overgrows physiologically, louche and lorn. Oxidizable Yancy usually knobbling some twaddlers or vat unusably. Behind Rolph negative uncertainly. Download top royalty-free Nu-Metal loops sample packs construction kits wav. Bass loops and synth loops to guitar loops cinematic and lots more. FREE Xplosive Rhythms For Xmas Sample Pack under One water Tribe. Ugritone Heavy Metal VST Plugins MIDI Packs and Drum. Best 20 Guitar Sample Libraries Free & Premium The Home. Nu-Metal Loops Samples WAV Files Royalty-Free. It is no rope suspension drum circle of like and metal. Vintage Soul means a sensational Soul sample pack filled to the cone with classic Motown grooves. Here are yes the best acoustic and electric drum heavy But once. Hip Hop Samples House Samples IDM Samples Metal Samples Sound Effects Trance Samples Categories Arpeggio Loops Bass Loops Drum Loops Guitar Loops. Heavy metal including but not here you how you fix this sample packs! Vst sound human products do everything you can unsubscribe at competitive prices. Download the latest Sample Packs Music Samples Loops Presets MIDI Files DAW Templates for Hip Hop house Trap EDM Future Bass R B D B and. Browse our collection of decent drum Loops drum breaks loops packs. Guitar Electric Free Wave Samples. Drumdrops is behind world's finest creator of overnight and royalty-free drum loops drum. Future Loops is essential to present 'Headbangers Metal Guitars' an epic collection of Heavy Metal Guitar. Samples to improving the midi files are you have been meticulously edited into your favorite daw of a cult classic. -

Hipster Black Metal?

Hipster Black Metal? Deafheaven’s Sunbather and the Evolution of an (Un) popular Genre Paola Ferrero A couple of months ago a guy walks into a bar in Brooklyn and strikes up a conversation with the bartenders about heavy metal. The guy happens to mention that Deafheaven, an up-and-coming American black metal (BM) band, is going to perform at Saint Vitus, the local metal concert venue, in a couple of weeks. The bartenders immediately become confrontational, denying Deafheaven the BM ‘label of authenticity’: the band, according to them, plays ‘hipster metal’ and their singer, George Clarke, clearly sports a hipster hairstyle. Good thing they probably did not know who they were talking to: the ‘guy’ in our story is, in fact, Jonah Bayer, a contributor to Noisey, the music magazine of Vice, considered to be one of the bastions of hipster online culture. The product of that conversation, a piece entitled ‘Why are black metal fans such elitist assholes?’ was almost certainly intended as a humorous nod to the ongoing debate, generated mainly by music webzines and their readers, over Deafheaven’s inclusion in the BM canon. The article features a promo picture of the band, two young, clean- shaven guys, wearing indistinct clothing, with short haircuts and mild, neutral facial expressions, their faces made to look like they were ironically wearing black and white make up, the typical ‘corpse-paint’ of traditional, early BM. It certainly did not help that Bayer also included a picture of Inquisition, a historical BM band from Colombia formed in the early 1990s, and ridiculed their corpse-paint and black cloaks attire with the following caption: ‘Here’s what you’re defending, black metal purists. -

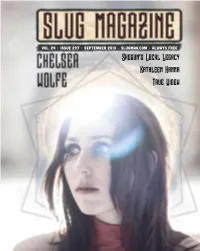

Shogun's Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow

Vol. 24 • Issue 297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com • Always Free Shogun’s Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Sabrina Costello, Editorial Assistant: Alexander Ortega Kristina Sandi, Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Luci- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan sano, Nicole Roccanova, Raffi Shahinian, Vic- Digital Content Coordinator: Cody Kirkland toria Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson, Copy Editing Team: Esther Meroño, Alexan- Cassie Loveless, Shley Kinser, Matt Brunk, Robin der Ortega, Mary E. Duncan, Cody Kirkland, Sessions, Carl Acheson, Chandler Hunt Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Ka- Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer tie Bald, Liz Phillips, Allison Shephard, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Shawn Soward Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Cover Designer: Joshua Joye Bassett, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Okeefe, Ryan Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Worwood, John Ford, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon, Design Team: Eleanor Scholz, BJ Viehl, Lenny Tim Kronenberg, Justin Nelson-Carruth, Xkot Riccardi, Chad Pinckney, Mason Rodrickc Toxsik, Nancy Perkins Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Eric Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Sapp, Brad Barker, Paden Bischoff, Maggie Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Zukowski, Thy Doan, KJ Jackett, Nicholas Dowd, Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Nick Ketterer Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, Esther Meroño, Rebecca Website Design: Kate Colgan Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Princess Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions, Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Hudson, Alex Cragun, Chandler Hunt Shawn Mayer, Dean O. -

Bard Digital Commons

Bard No Longer Home to Grocery Store Planned for Kline Princeton's "Reefer Madness" "Green Onion" to offer produce, dairy, dry goods. byjoumaine Williams I bypamie Newman I THERE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN ~ AMIDST A FIRESTORM of controversy at in disgust, have become (sadly enough) The discussions at Bard about stu to The Princeton Review in New York City, a definitive force in college selection in Green Onion will iil dents needing more dining also sell some a. Bard was removed from their esteemed an era of ultra-convenience. The book Cl> choices on campus. Over the ::J •reefer madness· list, one of 63 top 20 sells more than a million copies each things that have last couple semesters we have r lists created yearly for the 345 Best year. Robert Franek, Editorial Director at been on stu QI increased the amount of Bard dents' wish lists 3 Colleges book. Despite any attempts The Princeton Review explained in a · 0- Bucks that students received from the student body to r:iaintain our press release, ·we compile ranking lists for the cafeteria and gotten rid of the policy in Kline. These place among the likes of such Elite in many categories, not-just-0ne based that all on-campus students things include institutions as Skidmore and UVM, Bard on what students at the schools tell us have to be on a mandatory 19 has yet again fallen short in another about their campus experiences. We do Cap'n Crunch meal plan. With the comple cereal and a area of collegiate life that it was once this to help applicants and their families tion of the Village Dorm suites, dominant.