Surfactant Cleaners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate

Catalog Number: 102918, 190522, 194831, 198957, 811030, 811032, 811033, 811034, 811036 Sodium dodecyl sulfate Structure: Molecular Formula: C12H25NaSO4 Molecular Weight: 288.38 CAS #: 151-21-3 Synonyms: SDS; Lauryl sulfate sodium salt; Dodecyl sulfate sodium salt; Dodecyl sodium sulfate; Sodium lauryl sulfate; Sulfuric acid monododecyl ester sodium salt Physical Appearance: White granular powder Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC): 8.27 mM (Detergents with high CMC values are generally easy to remove by dilution; detergents with low CMC values are advantageous for separations on the basis of molecular weight. As a general rule, detergents should be used at their CMC and at a detergent-to-protein weight ratio of approximately ten. 13,14 Aggregation Number: 62 Solubility: Soluble in water (200 mg/ml - clear, faint yellow solution), and ethanol (0.1g/10 ml) Description: An anionic detergent3 typically used to solubilize8 and denature proteins for electrophoresis.4,5 SDS has also been used in large-scale phenol extraction of RNA to promote the dissociation of protein from nucleic acids when extracting from biological material.12 Most proteins bind SDS in a ratio of 1.4 grams SDS to 1 gram protein. The charges intrinsic to the protein become insignificant compared to the overall negative charge provided by the bound SDS. The charge to mass ratio is essentially the same for each protein and will migrate in the gel based only on protein size. Typical Working Concentration: > 10 mg SDS/mg protein Typical Buffer Compositions: SDS Electrophoresis -

Effects of Surfactants on the Toxicitiy of Glyphosate, with Specific Reference to RODEO

SERA TR 97-206-1b Effects of Surfactants on the Toxicitiy of Glyphosate, with Specific Reference to RODEO Submitted to: Leslie Rubin, COTR Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Biotechnology, Biologics and Environmental Protection Environmental Analysis and Documentation United States Department of Agriculture Suite 5A44, Unit 149 4700 River Road Riverdale, MD 20737 Task No. 5 USDA Contract No. 53-3187-5-12 USDA Order No. 43-3187-7-0028 Prepared by: Gary L. Diamond Syracuse Research Corporation Merrill Lane Syracuse, NY 13210 and Patrick R. Durkin Syracuse Environmental Research Associates, Inc. 5100 Highbridge St., 42C Fayetteville, New York 13066-0950 Telephone: (315) 637-9560 Fax: (315) 637-0445 CompuServe: 71151,64 Internet: [email protected] February 6, 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................... iii 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................1 2. CONSTITUENTS OF SURFACTANT FORMULATIONS USED WITH RODE0 ....4 2.1. AGRI-DEX ..........................................4 2.2. LI-700 .............................................4 2.3. R-11 ...............................................6 2.4. LATRON AG-98 ......................................6 2.5. LATRON AG-98 AG ....................................7 3. INFORMATION ON EFFECTS OF SURFACTANT FORMULATIONS ON THE TOXICITY OF RODEO ................................8 3.1. HUMAN HEALTH ......................................8 3.1.1. LI 700 ........................................8 3.1.2. Phosphatidylcholine ................................8 -

Is Colonic Propionate Delivery a Novel Solution to Improve Metabolism and Inflammation in Overweight Or Obese Subjects?

Commentary in IgG levels in IPE-treated subjects versus Is colonic propionate delivery a novel those receiving cellulose supplementa- tion. This interesting discovery is the Gut: first published as 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318776 on 26 April 2019. Downloaded from solution to improve metabolism and first evidence in humans that promoting the delivery of propionate in the colon inflammation in overweight or may affect adaptive immunity. It is worth noting that previous preclinical and clin- obese subjects? ical data have shown that supplementation with inulin-type fructans was associated 1,2 with a lower inflammatory tone and a Patrice D Cani reinforcement of the gut barrier.7 8 Never- theless, it remains unknown if these effects Increased intake of dietary fibre has been was the lack of evidence that the observed are directly linked with the production of linked to beneficial impacts on health for effects were due to the presence of inulin propionate, changes in the proportion of decades. Strikingly, the exact mechanisms itself on IPE or the delivery of propionate the overall levels of SCFAs, or the pres- of action are not yet fully understood. into the colon. ence of any other bacterial metabolites. Among the different families of fibres, In GUT, Chambers and colleagues Alongside the changes in the levels prebiotics have gained attention mainly addressed this gap of knowledge and of SCFAs, plasma metabolome analysis because of their capacity to selectively expanded on their previous findings.6 For revealed that each of the supplementa- modulate the gut microbiota composition 42 days, they investigated the impact of tion periods was correlated with different 1 and promote health benefits. -

Pulmonary Surfactant: the Key to the Evolution of Air Breathing Christopher B

Pulmonary Surfactant: The Key to the Evolution of Air Breathing Christopher B. Daniels and Sandra Orgeig Department of Environmental Biology, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia Pulmonary surfactant controls the surface tension at the air-liquid interface within the lung. This sys- tem had a single evolutionary origin that predates the evolution of the vertebrates and lungs. The lipid composition of surfactant has been subjected to evolutionary selection pressures, partic- ularly temperature, throughout the evolution of the vertebrates. ungs have evolved independently on several occasions pendent units, do not necessarily stretch upon inflation but Lover the past 300 million years in association with the radi- unpleat or unfold in a complex manner. Moreover, the many ation and diversification of the vertebrates, such that all major fluid-filled corners and crevices in the alveoli open and close vertebrate groups have members with lungs. However, lungs as the lung inflates and deflates. differ considerably in structure, embryological origin, and Surfactant in nonmammals exhibits an antiadhesive func- function between vertebrate groups. The bronchoalveolar lung tion, lining the interface between apposed epithelial surfaces of mammals is a branching “tree” of tubes leading to millions within regions of a collapsed lung. As the two apposing sur- of tiny respiratory exchange units, termed alveoli. In humans faces peel apart, the lipids rise to the surface of the hypophase there are ~25 branches and 300 million alveoli. This structure fluid at the expanding gas-liquid interface and lower the sur- allows for the generation of an enormous respiratory surface face tension of this fluid, thereby decreasing the work required area (up to 70 m2 in adult humans). -

The Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST) Transition

Copyright by David Samuel Simmons 2009 The Dissertation Committee for David Samuel Simmons certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Phase and Conformational Behavior of LCST-Driven Stimuli Responsive Polymers Committee: ______________________________ Isaac Sanchez, Supervisor ______________________________ Nicholas Peppas ______________________________ Krishnendu Roy ______________________________ Venkat Ganesan ______________________________ Thomas Truskett Phase and Conformational Behavior of LCST-Driven Stimuli Responsive Polymers by David Samuel Simmons, B.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2009 To my grandfather, who made me an engineer before I knew the word and to my wife, Carey, for being my partner on my good days and bad. Acknowledgements I am extraordinarily fortunate in the support I have received on the path to this accomplishment. My adviser, Dr. Isaac Sanchez, has made this publication possible with his advice, support, and willingness to field my ideas at random times in the afternoon; he has my deep appreciation for his outstanding guidance. My thanks also go to the members of my Ph.D. committee for their valuable feedback in improving my research and exploring new directions. I am likewise grateful to the other members of Dr. Sanchez’ research group – Xiaoyan Wang, Yingying Jiang, Xiaochu Wang, and Frank Willmore – who have shared their ideas and provided valuable sounding boards for my mine. I would particularly like to express appreciation for Frank’s donation of his own post-graduation time in assisting my research. -

Tutorial on Working with Micelles and Other Model Membranes

Tutorial on Working with Micelles and Model Membranes Chuck Sanders Dept. of Biochemistry, Dept. of Medicine, and Center for Structural Biology Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. http://structbio.vanderbilt.edu/sanders/ March, 2017 There are two general classes of membrane proteins. This presentation is on working with integral MPs, which traditionally could be removed from the membrane only by dissolving the membrane with detergents or organic solvents. Multilamellar Vesicles: onion-like assemblies. Each layer is one bilayer. A thin layer of water separates each bilayer. MLVs are what form when lipid powders are dispersed in water. They form spontaneously. Cryo-EM Micrograph of a Multilamellar Vesicle (K. Mittendorf, C. Sanders, and M. Ohi) Unilamellar Multilamellar Vesicle Vesicle Advances in Anesthesia 32(1):133-147 · 2014 Energy from sonication, physical manipulation (such as extrusion by forcing MLV dispersions through filters with fixed pore sizes), or some other high energy mechanism is required to convert multilayered bilayer assemblies into unilamellar vesicles. If the MLVs contain a membrane protein then you should worry about whether the protein will survive these procedures in folded and functional form. Vesicles can also be prepared by dissolving lipids using detergents and then removing the detergent using BioBeads-SM dialysis, size exclusion chromatography or by diluting the solution to below the detergent’s critical micelle concentration. These are much gentler methods that a membrane protein may well survive with intact structure and function. From: Avanti Polar Lipids Catalog Bilayers can undergo phase transitions at a critical temperature, Tm. Native bilayers are usually in the fluid (liquid crystalline) phase. -

Henry's Law Constants and Micellar Partitioning of Volatile Organic

38 J. Chem. Eng. Data 2000, 45, 38-47 Henry’s Law Constants and Micellar Partitioning of Volatile Organic Compounds in Surfactant Solutions Leland M. Vane* and Eugene L. Giroux United States Environmental Protection Agency, National Risk Management Research Laboratory, 26 West Martin Luther King Drive, Cincinnati, Ohio 45268 Partitioning of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into surfactant micelles affects the apparent vapor- liquid equilibrium of VOCs in surfactant solutions. This partitioning will complicate removal of VOCs from surfactant solutions by standard separation processes. Headspace experiments were performed to quantify the effect of four anionic surfactants and one nonionic surfactant on the Henry’s law constants of 1,1,1-trichloroethane, trichloroethylene, toluene, and tetrachloroethylene at temperatures ranging from 30 to 60 °C. Although the Henry’s law constant increased markedly with temperature for all solutions, the amount of VOC in micelles relative to that in the extramicellar region was comparatively insensitive to temperature. The effect of adding sodium chloride and isopropyl alcohol as cosolutes also was evaluated. Significant partitioning of VOCs into micelles was observed, with the micellar partitioning coefficient (tendency to partition from water into micelle) increasing according to the following series: trichloroethane < trichloroethylene < toluene < tetrachloroethylene. The addition of surfactant was capable of reversing the normal sequence observed in Henry’s law constants for these four VOCs. Introduction have long taken advantage of the high Hc values for these compounds. In the engineering field, the most common Vast quantities of organic solvents have been disposed method of dealing with chlorinated solvents dissolved in of in a manner which impacts human health and the groundwater is “pump & treat”swithdrawal of ground- environment. -

Dive Theory Guide

DIVE THEORY STUDY GUIDE by Rod Abbotson CD69259 © 2010 Dive Aqaba Guidelines for studying: Study each area in order as the theory from one subject is used to build upon the theory in the next subject. When you have completed a subject, take tests and exams in that subject to make sure you understand everything before moving on. If you try to jump around or don’t completely understand something; this can lead to gaps in your knowledge. You need to apply the knowledge in earlier sections to understand the concepts in later sections... If you study this way you will retain all of the information and you will have no problems with any PADI dive theory exams you may take in the future. Before completing the section on decompression theory and the RDP make sure you are thoroughly familiar with the RDP, both Wheel and table versions. Use the appropriate instructions for use guides which come with the product. Contents Section One PHYSICS ………………………………………………page 2 Section Two PHYSIOLOGY………………………………………….page 11 Section Three DECOMPRESSION THEORY & THE RDP….……..page 21 Section Four EQUIPMENT……………………………………………page 27 Section Five SKILLS & ENVIRONMENT…………………………...page 36 PHYSICS SECTION ONE Light: The speed of light changes as it passes through different things such as air, glass and water. This affects the way we see things underwater with a diving mask. As the light passes through the glass of the mask and the air space, the difference in speed causes the light rays to bend; this is called refraction. To the diver wearing a normal diving mask objects appear to be larger and closer than they actually are. -

Biomechanics of Safe Ascents Workshop

PROCEEDINGS OF BIOMECHANICS OF SAFE ASCENTS WORKSHOP — 10 ft E 30 ft TIME AMERICAN ACADEMY OF UNDERWATER SCIENCES September 25 - 27, 1989 Woods Hole, Massachusetts Proceedings of the AAUS Biomechanics of Safe Ascents Workshop Michael A. Lang and Glen H. Egstrom, (Editors) Copyright © 1990 by AMERICAN ACADEMY OF UNDERWATER SCIENCES 947 Newhall Street Costa Mesa, CA 92627 All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by photostat, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publishers Copies of these Proceedings can be purchased from AAUS at the above address This workshop was sponsored in part by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Department of Commerce, under grant number 40AANR902932, through the Office of Undersea Research, and in part by the Diving Equipment Manufacturers Association (DEMA), and in part by the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS). The U.S. Government is authorized to produce and distribute reprints for governmental purposes notwithstanding the copyright notation that appears above. Opinions presented at the Workshop and in the Proceedings are those of the contributors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences PROCEEDINGS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF UNDERWATER SCIENCES BIOMECHANICS OF SAFE ASCENTS WORKSHOP WHOI/MBL Woods Hole, Massachusetts September 25 - 27, 1989 MICHAEL A. LANG GLEN H. EGSTROM Editors American Academy of Underwater Sciences 947 Newhall Street, Costa Mesa, California 92627 U.S.A. An American Academy of Underwater Sciences Diving Safety Publication AAUSDSP-BSA-01-90 CONTENTS Preface i About AAUS ii Executive Summary iii Acknowledgments v Session 1: Introductory Session Welcoming address - Michael A. -

Exercise and Cellular Respiration Lab

California State University of Bakersfield, Department of Chemistry Exercise and Cellular Respiration Lab Standards: MS-LS1-7 Develop a model to describe how food is rearranged through chemical reactions forming new molecules that support growth and/or release energy as this matter moves through an organism. Introduction: I. Background Information. Cellular respiration (see chemical reaction below) is a chemical reaction that occurs in your cells to create energy; when you are exercising your muscle cells are creating ATP to contract. Cellular respiration requires oxygen (which is breathed in) and creates carbon dioxide (which is breathed out). This lab will address how exercise (increased muscle activity) affects the rate of cellular respiration. You will measure 3 different indicators of cellular respiration: breathing rate, heart rate, and carbon dioxide production. You will measure these indicators at rest (with no exercise) and after 1 and 2 minutes of exercise. Breathing rate is measured in breaths per minute, heart rate in beats per minute, and carbon dioxide in the time it takes bromothymol blue to change color. Carbon dioxide production can be measured by breathing through a straw into a solution of bromothymol blue (BTB). BTB is an acid indicator; when it reacts with acid it turns from blue to yellow. When carbon dioxide reacts with water, a weak acid (carbonic acid) is formed (see chemical reaction below). The more carbon dioxide you breathe into the BTB solution, the faster it will change color to yellow. The purpose of this lab activity is to analyze the effect of exercise on cellular respiration. Background: I. -

Effect of Surfactant on Interfacial Gas Transfer Studied by Axisymmetric Drop Shape Analysis-Captive Bubble (ADSA-CB)

5446 Langmuir 2005, 21, 5446-5452 Effect of Surfactant on Interfacial Gas Transfer Studied by Axisymmetric Drop Shape Analysis-Captive Bubble (ADSA-CB) Yi Y. Zuo,† Dongqing Li,† Edgar Acosta,‡ Peter N. Cox,§ and A. Wilhelm Neumann*,† Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, University of Toronto, 5 King’s College Road, Toronto, ON, M5S 3G8, Canada, Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, University of Toronto, 200 College Street, Toronto, ON, M5S 3E5, Canada, and Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Avenue, Toronto, ON, M5G 1X8, Canada Received January 31, 2005. In Final Form: April 3, 2005 A new method combining axisymmetric drop shape analysis (ADSA) and a captive bubble (CB) is proposed to study the effect of surfactant on interfacial gas transfer. In this method, gas transfer from a static CB to the surrounding quiescent liquid is continuously recorded for a short period (i.e., 5 min). By photographical analysis, ADSA-CB is capable of yielding detailed information pertinent to the surface tension and geometry of the CB, e.g., bubble area, volume, curvature at the apex, and the contact radius and height of the bubble. A steady-state mass transfer model is established to evaluate the mass transfer coefficient on the basis of the output of ADSA-CB. In this way, we are able to develop a working prototype capable of simultaneously measuring dynamic surface tension and interfacial gas transfer. Other advantages of this method are that it allows for the study of very low surface tensions (<5 mJ/m2) and does not require equilibrium of gas transfer. -

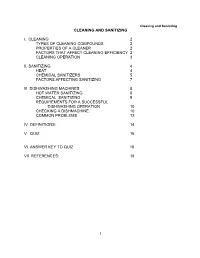

Cleaning and Sanitizing I. Cleaning 2 Types Of

Cleaning and Sanitizing CLEANING AND SANITIZING I. CLEANING 2 TYPES OF CLEANING COMPOUNDS 2 PROPERTIES OF A CLEANER 2 FACTORS THAT AFFECT CLEANING EFFICIENCY 2 CLEANING OPERATION 3 II. SANITIZING 4 HEAT 4 CHEMICAL SANITIZERS 5 FACTORS AFFECTING SANITIZING 7 III. DISHWASHING MACHINES 8 HOT WATER SANITIZING 8 CHEMICAL SANITIZING 9 REQUIREMENTS FOR A SUCCESSFUL DISHWASHING OPERATION 10 CHECKING A DISHMACHINE 10 COMMON PROBLEMS 12 IV. DEFINITIONS: 14 V. QUIZ 16 VI. ANSWER KEY TO QUIZ 18 VII. REFERENCES: 18 1 Cleaning and Sanitizing This section is presented primarily for information. The only information the BETC participant will be responsible for is to know the sanitization standards for chemical and hot water sanitizing as found in the Rules for Food Establishment Sanitation. CLEANING AND SANITIZING I. CLEANING Cleaning is a process which will remove soil and prevent accumulation of food residues which may decompose or support the growth of disease causing organisms or the production of toxins. Listed below are the five basic types of cleaning compounds and their major functions: 1. Basic Alkalis - Soften the water (by precipitation of the hardness ions), and saponify fats (the chemical reaction between an alkali and a fat in which soap is produced). 2. Complex Phosphates - Emulsify fats and oils, disperse and suspend oils, peptize proteins, soften water by sequestering, and provide rinsability characteristics without being corrosive. 3 Surfactant - (Wetting Agents) Emulsify fats, disperse fats, provide wetting properties, form suds, and provide rinsability characteristics without being corrosive. 4. Chelating - (Organic compounds) Soften the water by sequestering, prevent mineral deposits, and peptize proteins without being corrosive.