Music Notation and Theory for Intelligent Beginners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

An Adaptive Tuning System for MIDI Pianos

David Løberg Code Groven.Max: School of Music Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, MI 49008 USA An Adaptive Tuning [email protected] System for MIDI Pianos Groven.Max is a real-time program for mapping a renstemningsautomat, an electronic interface be- performance on a standard keyboard instrument to tween the manual and the pipes with a kind of arti- a nonstandard dynamic tuning system. It was origi- ficial intelligence that automatically adjusts the nally conceived for use with acoustic MIDI pianos, tuning dynamically during performance. This fea- but it is applicable to any tunable instrument that ture overcomes the historic limitation of the stan- accepts MIDI input. Written as a patch in the MIDI dard piano keyboard by allowing free modulation programming environment Max (available from while still preserving just-tuned intervals in www.cycling74.com), the adaptive tuning logic is all keys. modeled after a system developed by Norwegian Keyboard tunings are compromises arising from composer Eivind Groven as part of a series of just the intersection of multiple—sometimes oppos- intonation keyboard instruments begun in the ing—influences: acoustic ideals, harmonic flexibil- 1930s (Groven 1968). The patch was first used as ity, and physical constraints (to name but three). part of the Groven Piano, a digital network of Ya- Using a standard twelve-key piano keyboard, the maha Disklavier pianos, which premiered in Oslo, historical problem has been that any fixed tuning Norway, as part of the Groven Centennial in 2001 in just intonation (i.e., with acoustically pure tri- (see Figure 1). The present version of Groven.Max ads) will be limited to essentially one key. -

Dynamic Generation of Musical Notation from Musicxml Input on an Android Tablet

Dynamic Generation of Musical Notation from MusicXML Input on an Android Tablet THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Laura Lynn Housley Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Rajiv Ramnath, Advisor Jayashree Ramanathan Copyright by Laura Lynn Housley 2012 Abstract For the purpose of increasing accessibility and customizability of sheet music, an application on an Android tablet was designed that generates and displays sheet music from a MusicXML input file. Generating sheet music on a tablet device from a MusicXML file poses many interesting challenges. When a user is allowed to set the size and colors of an image, the image must be redrawn with every change. Instead of zooming in and out on an already existing image, the positions of the various musical symbols must be recalculated to fit the new dimensions. These changes must preserve the relationships between the various musical symbols. Other topics include the laying out and measuring of notes, accidentals, beams, slurs, and staffs. In addition to drawing a large bitmap, an application that effectively presents sheet music must provide a way to scroll this music across a small tablet screen at a specified tempo. A method for using animation on Android is discussed that accomplishes this scrolling requirement. Also a generalized method for writing text-based documents to describe notations similar to musical notation is discussed. This method is based off of the knowledge gained from using MusicXML. -

Kisd Band Ms 3 Curriculum Year at a Glance

KISD BAND MS 3 CURRICULUM YEAR AT A GLANCE TEXT: Essential Elements for Band THE LEARNER WILL: 1st 9-Weeks 2nd 9-Weeks 3rd 9-Weeks 4th 9-Weeks Identify, define, write, and analyze whole, half, quarter, paired and single Identify, define, write, and analyze all previously learned elements adding eighth, sixteenth, dotted half, and dotted quarter notes with corresponding 9/8, 12/8, and 5/4 time signatures and the keys of G and Db. (1B, 1D, 1C, rests in simple time and dotted quarters and triplets in compound time; 2B, 3F) multi-measure rests; repeat, first and second endings, da capo al fine, dal segno al fine, da capo al coda, dal segno al coda; dynamics (pp-ff); staccato, Identify, define, write and analyze all previously learned elements in addition to the following: largo-presto, sforzando, fortepiano, chord structures legato, accent, marcato; crescendo, decrescendo; 2/4, 3/4 ,4/4, 2/2, 6/8; keys and tuning in a major key. (1B, 1D, 1C, 2B, 3F) of Bb, Eb, F; instrument names; musical forms; fermata; andante, moderato, ritardando, accelerando, largo, adagio, allegro. (1B, 1D, 1C, 2B, 3F) Perform a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, fingerings, and Perform from memory a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, Perform from memory a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, Perform from memory a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, accurate intonation. (1B) fingerings, and accurate intonation (quarter = 80bpm utilizing an eighth fingerings and accurate intonation (quarter = 100bpm utilizing an eighth fingerings, and accurate intonation (quarter = 100bpm utilizing a triplet note pattern). -

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

New International Manual of Braille Music Notation by the Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union

1 New International Manual Of Braille Music Notation by The Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union Compiled by Bettye Krolick ISBN 90 9009269 2 1996 2 Contents Preface................................................................................ 6 Official Delegates to the Saanen Conference: February 23-29, 1992 .................................................... 8 Compiler’s Notes ............................................................... 9 Part One: General Signs .......................................... 11 Purpose and General Principles ..................................... 11 I. Basic Signs ................................................................... 13 A. Notes and Rests ........................................................ 13 B. Octave Marks ............................................................. 16 II. Clefs .............................................................................. 19 III. Accidentals, Key & Time Signatures ......................... 22 A. Accidentals ................................................................ 22 B. Key & Time Signatures .............................................. 22 IV. Rhythmic Groups ....................................................... 25 V. Chords .......................................................................... 30 A. Intervals ..................................................................... 30 B. In-accords .................................................................. 34 C. Moving-notes ............................................................ -

The Baroque. 3.3: Vocal Music: the Da Capo Aria and Other Types of Arias

UNIT 3: THE BAROQUE. 3.3: VOCAL MUSIC: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS EXPLANATION 3.3: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS. THE ARIA The aria in the operas is the part sung by the soloist. It is opposed to the recitative, which uses the recitative style. In the arias the composer shows and exploits the dramatic and emotional situations, it becomes the equivalent of a soliloquy (one person speach) in the spoken plays. In the arias, the interpreters showed their technique, they showed off, even in excess, which provoked a lot of criticism from poets and musicians. They were often sung by castrati: soprano men undergoing a surgical operation so as not to change their voice when they grew up. One of them, the most famous, Farinelli, acquired international fame for his great technique and vocal expression. He lived twenty-five years in Spain. THE DA CAPO ARIA The Da Capo aria is a vocal work in three parts or sections (tripartite form). It began to be used in the Baroque in operas, oratorios and cantatas. The form is A - B - A, the last part being a repetition of the first. 1. The first section is a complete musical entity, that is to say, it could be sung alone and musically it would have complete meaning since it ends in the tonic. The tonic is the first grade or note of a scale. 2. The second section contrasts with the first section in tonality, texture, mood and sometimes in tempo (speed). 3. -

10 - Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1

Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef Chapter 2. Bass Clef In this chapter you will: 1.Write bass clefs 2. Write some low notes 3. Match low notes on the keyboard with notes on the staff 4. Write eighth notes 5. Identify notes on ledger lines 6. Identify sharps and flats on the keyboard 7.Write sharps and flats on the staff 8. Write enharmonic equivalents date: 2.1 Write bass clefs • The symbol at the beginning of the above staff, , is an F or bass clef. • The F or bass clef says that the fourth line of the staff is the F below the piano’s middle C. This clef is used to write low notes. DRAW five bass clefs. After each clef, which itself includes two dots, put another dot on the F line. © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 10 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef 2.2 Write some low notes •The notes on the spaces of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom space are: A, C, E and G as in All Cows Eat Grass. •The notes on the lines of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom line are: G, B, D, F and A as in Good Boys Do Fine Always. 1. IDENTIFY the notes in the song “This Old Man.” PLAY it. 2. WRITE the notes and bass clefs for the song, “Go Tell Aunt Rhodie” Q = quarter note H = half note W = whole note © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 11 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. -

Use of Scale Modeling for Architectural Acoustic Measurements

Gazi University Journal of Science Part B: Art, Humanities, Design And Planning GU J Sci Part:B 1(3):49-56 (2013) Use of Scale Modeling for Architectural Acoustic Measurements Ferhat ERÖZ 1,♠ 1 Atılım University, Department of Interior Architecture & Environmental Design Received: 09.07.2013 Accepted:01.10.2013 ABSTRACT In recent years, acoustic science and hearing has become important. Acoustic design tests used in acoustic devices is crucial. Sound propagation is a complex subject, especially inside enclosed spaces. From the 19th century on, the acoustic measurements and tests were carried out using modeling techniques that are based on room acoustic measurement parameters. In this study, the effects of architectural acoustic design of modeling techniques and acoustic parameters were investigated. In this context, the relationships and comparisons between physical, scale, and computer models were examined. Key words: Acoustic Modeling Techniques, Acoustics Project Design, Acoustic Parameters, Acoustic Measurement Techniques, Cavity Resonator. 1. INTRODUCTION (1877) “Theory of Sound”, acoustics was born as a science [1]. In the 20th century, especially in the second half, sound and noise concepts gained vast importance due to both A scientific context began to take shape with the technological and social advancements. As a result of theoretical sound studies of Prof. Wallace C. Sabine, these advancements, acoustic design, which falls in the who laid the foundations of architectural acoustics, science of acoustics, and the use of methods that are between 1898 and 1905. Modern acoustics started with related to the investigation of acoustic measurements, studies that were conducted by Sabine and auditory became important. Therefore, the science of acoustics quality was related to measurable and calculable gains more and more important every day. -

An App to Find Useful Glissandos on a Pedal Harp by Bill Ooms

HarpPedals An app to find useful glissandos on a pedal harp by Bill Ooms Introduction: For many years, harpists have relied on the excellent book “A Harpist’s Survival Guide to Glisses” by Kathy Bundock Moore. But if you are like me, you don’t always carry all of your books with you. Many of us now keep our music on an iPad®, so it would be convenient to have this information readily available on our tablet. For those of us who don’t use a tablet for our music, we may at least have an iPhone®1 with us. The goal of this app is to provide a quick and easy way to find the various pedal settings for commonly used glissandos in any key. Additionally, it would be nice to find pedal positions that produce a gliss for common chords (when possible). Device requirements: The application requires an iPhone or iPad running iOS 11.0 or higher. Devices with smaller screens will not provide enough space. The following devices are recommended: iPhone 7, 7Plus, 8, 8Plus, X iPad 9.7-inch, 10.5-inch, 12.9-inch Set the pedals with your finger: In the upper window, you can set the pedal positions by tapping the upper, middle, or lower position for flat, natural, and sharp pedal position. The scale or chord represented by the pedal position is shown in the list below the pedals (to the right side). Many pedal positions do not form a chord or scale, so this window may be blank. Often, there are several alternate combinations that can give the same notes. -

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T

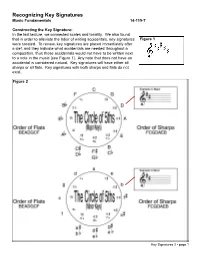

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T Constructing the Key Signature: In the last lecture, we connected scales and tonality. We also found that in order to alleviate the labor of writing accidentals, key signatures Figure 1 were created. To review, key signatures are placed immediately after a clef, and they indicate what accidentals are needed throughout a composition, thus those accidentals would not have to be written next to a note in the music [see Figure 1]. Any note that does not have an accidental is considered natural. Key signatures will have either all sharps or all flats. Key signatures with both sharps and flats do not exist. Figure 2 Key Signatures 2 - page 1 The Circle of 5ths: One of the easiest ways of recognizing key signatures is by using the circle of 5ths [see Figure 2]. To begin, we must simply memorize the key signature without any flats or sharps. For a major key, this is C-major and for a minor key, A-minor. After that, we can figure out the key signature by following the diagram in Figure 2. By adding one sharp, the key signature moves up a perfect 5th from what preceded it. Therefore, since C-major has not sharps or flats, by adding one sharp to the key signa- ture, we find G-major (G is a perfect 5th above C). You can see this by moving clockwise around the circle of 5ths. For key signatures with flats, we move counter-clockwise around the circle. Since we are moving “backwards,” it makes sense that by adding one flat, the key signature is a perfect 5th below from what preceded it. -

Key Relationships in Music

LearnMusicTheory.net 3.3 Types of Key Relationships The following five types of key relationships are in order from closest relation to weakest relation. 1. Enharmonic Keys Enharmonic keys are spelled differently but sound the same, just like enharmonic notes. = C# major Db major 2. Parallel Keys Parallel keys share a tonic, but have different key signatures. One will be minor and one major. D minor is the parallel minor of D major. D major D minor 3. Relative Keys Relative keys share a key signature, but have different tonics. One will be minor and one major. Remember: Relatives "look alike" at a family reunion, and relative keys "look alike" in their signatures! E minor is the relative minor of G major. G major E minor 4. Closely-related Keys Any key will have 5 closely-related keys. A closely-related key is a key that differs from a given key by at most one sharp or flat. There are two easy ways to find closely related keys, as shown below. Given key: D major, 2 #s One less sharp: One more sharp: METHOD 1: Same key sig: Add and subtract one sharp/flat, and take the relative keys (minor/major) G major E minor B minor A major F# minor (also relative OR to D major) METHOD 2: Take all the major and minor triads in the given key (only) D major E minor F minor G major A major B minor X as tonic chords # (C# diminished for other keys. is not a key!) 5. Foreign Keys (or Distantly-related Keys) A foreign key is any key that is not enharmonic, parallel, relative, or closely-related.