Front Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cognitive Psychology, 6Th Edition by Robert J. Sternberg and Karin Sternberg (Z-Lib.Org)

1 CHAPTER Introduction to Cognitive Psychology CHAPTER OUTLINE Cognitive Psychology Defined Three Cognitive Models of Intelligence Philosophical Antecedents of Psychology: Carroll: Three-Stratum Model of Intelligence Gardner: Theory of Multiple Intelligences Rationalism versus Empiricism Sternberg: The Triarchic Theory Psychological Antecedents of Intelligence of Cognitive Psychology Research Methods in Cognitive Psychology Early Dialectics in the Psychology of Cognition Goals of Research Understanding the Structure of the Mind: Distinctive Research Methods Structuralism Experiments on Human Behavior Understanding the Processes of the Mind: Psychobiological Research Functionalism Self-Reports, Case Studies, An Integrative Synthesis: Associationism and Naturalistic Observation It’s Only What You Can See That Counts: Computer Simulations and Artificial Intelligence From Associationism to Behaviorism Putting It All Together Proponents of Behaviorism Fundamental Ideas in Cognitive Psychology Criticisms of Behaviorism Behaviorists Daring to Peek into the Black Box Key Themes in Cognitive Psychology The Whole Is More Than the Sum of Its Parts: Summary Gestalt Psychology Thinking about Thinking: Analytical, Creative, Emergence of Cognitive Psychology and Practical Questions Early Role of Psychobiology Add a Dash of Technology: Engineering, Key Terms Computation, and Applied Cognitive Psychology Media Resources Cognition and Intelligence What Is Intelligence? 1 2 CHAPTER 1 • Introduction to Cognitive Psychology Here are some of the questions we will explore in this chapter: 1. What is cognitive psychology? 2. How did psychology develop as a science? 3. How did cognitive psychology develop from psychology? 4. How have other disciplines contributed to the development of theory and research in cognitive psychology? 5. What methods do cognitive psychologists use to study how people think? 6. -

Print This Article

Learnings, However Wise colorful narrative. The chapter is organized as much by experience as chronology, with Lyn Corno six key sections. Readers can find one- sentence lessons signaled by underlined material located at the start of some paragraphs within each key section. Why and How Educational Research I was an Arizona girl, born near the Grand Canyon, where my father had his first teaching job, and raised in Tempe just a short walk from Arizona State University. I was ready to leave home as soon as I finished college. As a child, my grandmother took me on bus trips to California, where beaches and flowering tree gardens lured me away from desert landscapes and endless days of sun. I wrote this chapter during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. How coincidental it is to be writing a reflective memoir at a time when it is hard to avoid reflecting. I had not thought I could tackle this project until well into the year, but sequestration at a rented house in South Carolina gave me time and so the pages multiplied in a different way. With this said, what is omitted is often the First grade photo, Broadmoor School, Tempe, most important material for reflection - the AZ emotional moments of childhood and the feelings that come with each turn of event. My parents appreciated my independent This is to be an account of things I may streak and, after helping me set up a studio have learned, however “wise,” for graduate apartment in Seal Beach, California, near my students or others who would have careers first job, my mother boarded a plane home in education and psychology, so it lacks a and left me to it. -

An Academic Genealogy of Psychometric Society Presidents

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) An Academic Genealogy of Psychometric Society Presidents Wijsen, L.D.; Borsboom, D.; Cabaço, T.; Heiser, W.J. DOI 10.1007/s11336-018-09651-4 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in Psychometrika License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wijsen, L. D., Borsboom, D., Cabaço, T., & Heiser, W. J. (2019). An Academic Genealogy of Psychometric Society Presidents. Psychometrika, 84(2), 562-588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-018-09651-4 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 psychometrika—vol. 84, no. 2, 562–588 June 2019 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-018-09651-4 AN ACADEMIC GENEALOGY OF PSYCHOMETRIC SOCIETY PRESIDENTS Lisa D. -

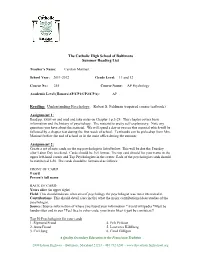

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Reading

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Teacher’s Name: Carolyn Marinari School Year: 2011-2012______________ Grade Level: 11 and 12 Course No.: 255 Course Name: AP Psychology Academic Level (Honors/AP/CP1/CP2/CPA): AP Reading: Understanding Psychology, Robert S. Feldman (required course textbook) Assignment 1: Read pp. xxxiv-iii and read and take notes on Chapter 1 p.3-29. This chapter covers basic information and the history of psychology. The material is pretty self-explanatory. Note any questions you have about the material. We will spend a day or two on this material which will be followed by a chapter test during the first week of school. Textbooks can be picked up from Mrs. Marinari before the end of school or in the main office during the summer. Assignment 2: Create a set of note cards on the top psychologists listed below. This will be due the Tuesday after Labor Day weekend. Cards should be 3x5 format. The top card should list your name in the upper left-hand corner and Top Psychologists in the center. Each of the psychologist cards should be numbered 1-50. The cards should be formatted as follows: FRONT OF CARD # card Person's full name BACK OF CARD Years alive (in upper right) Field: This should indicate what area of psychology the psychologist was most interested in. Contributions: This should detail (succinctly) what the major contributions/ideas/studies of the psychologist. Source: Source information of where you found your information *Avoid wikipedia *Must be handwritten and in pen *Feel free to color-code, your brain likes it-just be consistent!! Top 50 Psychologists for your cards 1. -

Research and Development Center for Teacher Education, the University of Texas

REPORT RESUMES ED 013 981 24 AA 000 252 RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CENTER FOR TEACHER EDUCATION, THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS. BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE MEMORANDUM NUMBER 13, PARTS A AND B. BY- MCGUIRE, CARSON TEXAS UNIV., AUSTIN, R! AND DEV. CTR. FOR ED. REPORT NUMBER BR- 23 PUB DATE 67 CONTRACT OEC-0 106 EDRS PRICE -$0.25 HC-$2.00 46P. DESCRIPTORS- *BIBLIOGRAPHIES, *ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHIES, *TEACHER EDUCATION, *BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES, *EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY, ELEMENTARY EDUCATION, SECONDARY EDUCATION PART A OF MIS MEMORANDUM IS AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR INSTRUCTORS IN TEACHER EDUCATION. PART B PRESENTS AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY THAT IS INTENDED AS AN ADDENDUM TO "BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE RESEARCH MEMORANDUMS" NUMBERS 10 AND 12. THESE BIBLIOGRAPHIES REPORT UPON TEXTS, BOOKS OF READINGS, SELECTED JOURNAL ARTICLES, VARIOUS MONOGRAPHS, AND RECENT BOOKS UPON TOPICS PERTINENT TO TEACHER EDUCATION. THE REFERENCES WERE COMPILED BY INSTRUCTORS OF EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY COURSES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AND BY RESEARCH PERSONNEL OF THE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CENTER FOR TEACHER EDUCATION LOCATED AT THE UNIVERSITY. THE AUTHOR STATES MOST OF THE REFERENCES ARE RELEVANT TO THE COURSE "BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES IN EDUCATION" OFFERED AT THE UNIVERSITY FOR BOTH ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION SECTIONS, (AL) AltC- 0A-q7- r A RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CENTER FOR TEACHER EDUCATION THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS , Behavioral Science Memorandum No. 13 This issue of the BSR Memo series reports upon texts, books of readings,selected journal ar- ia*. tidies, various monographs, and recent books upon topics pertinent toteacher education.Most of CC) the references are relevant to a course "Behavioral Sciences inEducation" (Elementary and Second- ary Education sections) offered at The University of Texas. -

Summer Assignment 2021

Welcome to AP Psychology! 2021 SUMMER ASSIGNMENT Ms. Nordone I am excited that you have decided to schedule this class and challenge yourself with the fascinating world of psychology. I am certain that you will find this course worthwhile and personally relevant. Although it is the summer, there is work to be done. Please note, AP Psychology is an elective, college-level course with higher student expectations than most courses taken by high school students. With that being said, it is imperative that we get a jump start on the AP Psychology curriculum. It is mandatory and, in your best interest, to complete the summer assignment. Your summer assignment consists of FOUR mini-assignments. Each assignment will serve a specific purpose that will assist you throughout the school year and aid in your preparations for the AP Exam in May, 2022. Summer Assignment #1 – “ Who’s Who?” Create Your Cards! Names to Know for the AP Psychology Exam Directions: You will create either a set of cards for the 38 most influential Psychologists. Using a reputable web source (www.famouspsychologists.org) or another search engine of your choice, look up each of the names below and research each of these psychologists. Use the template provided in Google Classroom or another program that designs flash cards. Read about their studies, their theories, and influential research relative to the field of psychology. On your flash card you should provide the person’s name and a detailed description of these things. (i.e. what they are most famous for in the field of -

International Journal of Scientific Research and Reviews Meaning

Islam Md. Nijairul, IJSRR 2018, 7(4), 1969-1982 Research article Available online www.ijsrr.org ISSN: 2279–0543 International Journal of Scientific Research and Reviews Meaning and nature of human intelligence: A review Islam Md. Nijairul Gazole Mahavidyalaya, Malda, West Bengal, India. PIN 732124. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT How to define intelligence seems to be a conundrum with human race. People have been pondering over the nature of intelligence for millennia. Simply put, intelligence is the ability to learn about, learn from, understand and interact with one‟s environment. This mental ability helps one in the task of theoretical as well as practical manipulation of things, objects or events present in one‟s environment in order to adapt to or face new challenges and problems of life as successfully as possible. Some psychometric theorists like Spearman believed that intelligence is a basic ability that affects performance on all cognitively oriented tasks – from computing mathematical problems to writing poetry or solving riddles, and that it can be measured through IQ tests. On the other hand, cognitive theorists like Earl B. Hunt hold that intelligence comprises of a set of mental representations of information and a set of processes that can operate on the mental representations. The latest ones – cognitive-contextual theorists of intelligence such as Howard Gardner – think that cognitive processes operate in various environmental contexts. The present paper tries to understand the meaning and nature of human intelligence from various perspectives, development of intelligence, and its measurement. KEY WORDS: Intelligence, understanding, psychometric theory, cognitive theory, cognitive- contextual theory. -

Copyrighted Material

CHAPTER 1 Educational Psychology: Contemporary Perspectives WILLIAM M. REYNOLDS AND GLORIA E. MILLER INTRODUCTION TO EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY IN THE SCHOOLS 12 PSYCHOLOGY 1 PERSPECTIVES ON EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS, CURRENT PRESENTATIONS OF THE FIELD 3 RESEARCH, AND POLICY 15 DISTINCTIVENESS OF THIS VOLUME 4 SUMMARY 18 OVERVIEW OF THIS VOLUME 5 REFERENCES 18 EARLY EDUCATION AND CURRICULUM APPLICATIONS 10 INTRODUCTION TO EDUCATIONAL assessment of intelligence and the study of gifted chil- PSYCHOLOGY dren (as well as related areas such as educational tracking), was monumental at this time and throughout much of the The field of educational psychology traces its begin- 20th century. Others, such as Huey (1900, 1901, 1908) nings to some of the major figures in psychology at were conducting groundbreaking psychological research the turn of the past century. William James at Harvard to advance the understanding of important educational University, who is often associated with the founding fields such as reading and writing. Further influences on of psychology in the United States, in the late 1800s educational psychology, and its impact on the field of edu- published influential books on psychology (1890) and edu- cation, have been linked to European philosophers of the cational psychology (1899). Other major theorists and mid- and late 19th century. For example, the impact of thinkers that figure in the early history of the field include Herbart on educational reforms and teacher preparation in G. Stanley Hall, John Dewey, and Edward L. Thorndike. the United States has been described by Hilgard (1996) Hall, cofounder of the American Psychological Asso- in his history of educational psychology. -

1 VITA NAME: Robert J. Sternberg ADDRESS: Department of Human Development, Cornell University, 116 Reservoir Ave., B44

VITA OF ROBERT J. STERNBERG 1 VITA NAME: Robert J. Sternberg ADDRESS: Department of Human Development, Cornell University, 116 Reservoir Ave., B44 MVR Hall, Ithaca, N 14853-4401 PHONE: 607-882-0001 E-MAIL: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., Stanford University, 1975 (Psychology); Advisor, Gordon Bower B.A., Yale University, 1972 (Psychology); Advisor, Endel Tulving Impact Indices (Google Scholar): Number of citations = 141,084 h index = 184 (number h of works cited at least h times) i10 Index = 900 (number of works cited at least 10 times) HONORS AND AWARDS Honorary Doctorates: Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Huelva, Spain, 2012 Doctor of Humanities, Honoris Causa, De la Salle University, Manila, Philippines, 2011 Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut, USA, 2009 Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, Eureka College, Illinois, USA, 2008 Doctor Honoris Causa, Ricardo Palma University, Peru, 2008 Doctor Honoris Causa, Tilburg University, Holland, 2007 Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, St. Petersburg State University, Russia, 2006 Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, University of Durham, England, 2006 Doctor Honoris Causa, Constantine the Philosopher University, Nitra, Slovakia, 2004 Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Leuven, Belgium, 2001 Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Cyprus, Cyprus, 2000 Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Paris V, France, 2000 Doctor Honoris Causa, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain, 1994 Scholarly Prizes and Awards: 1/20/2018 VITA OF ROBERT J. STERNBERG 2 Grawemeyer -

PCS AP Psych 0280

A Planned Course of Study for Advanced Placement Psychology ASHS Course # 0280 Abington School District Abington, Pennsylvania September, 2016 a. Objectives Students will demonstrate the appropriate level of proficiency in each of the following areas: History and Approaches • Recognize how philosophical and physiological perspectives shaped the development of psychological thought . • Describe and compare different theoretical approaches in explaining behavior: — structuralism, functionalism, and behaviorism in the early years; — Gestalt, psychoanalytic/psychodynamic, and humanism emerging later; — evolutionary, biological, cognitive, and biopsychosocial as more contemporary approaches . • Recognize the strengths and limitations of applying theories to explain behavior . • Distinguish the different domains of psychology (e .g ., biological, clinical, cognitive, counseling, developmental, educational, experimental, human factors, industrial–organizational, personality, psychometric, social) . • Identify major historical figures in psychology (e .g ., Mary Whiton Calkins, Charles Darwin, Dorothea Dix, Sigmund Freud, G . Stanley Hall, William James, Ivan Pavlov, Jean Piaget, Carl Rogers, B . F . Skinner, Margaret Floy Washburn, John B . Watson, Wilhelm Wundt) Research Methods • Differentiate types of research (e .g ., experiments, correlational studies, survey research, naturalistic observations, case studies) with regard to purpose, strengths, and weaknesses . • Describe how research design drives the reasonable conclusions that can be -

HD Scholarship in 2015

Department of Human Development/ HD Scholarship in 2015 HD Scholarship January 2015 Publications Sternberg, R.J., & Bridges, S.L. (2014). Varieties of genius. In D. K. Simonton (Ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of genius (pp. 185-197). New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell. Grant Awards Christopher Vredenburgh was recently awarded a two year National Research Service Award (NRSA) Individual Predoctoral Fellowship by the NIH to finish his dissertation work. He was also named one of 6 Department of Health and Human Services Head Start Graduate Student Research Scholars - 2 year grant funding his doctoral dissertation research. HD Scholarship February 2015 Publications Alea, N., & Wang, Q. (2015) (Eds.). Going global: The functions of autobiographical memory in cultural context. Special Issue in Memory, Volume 23, Issue 1. Hess, T., Strough, J. & Löckenhoff, C.E. (Eds.) (2015) Aging and decision making: Empirical and applied perspectives. Elsevier. Löckenhoff, C.E., Lee, D.S., Buckner, M.L., Moreira, M.O., Martinez, S.J. & Sun, M.Q. (2015). Cross-cultural differences in attitudes about aging: Moving beyond the East-West dichotomy. In S.T.Cheng, I. Chi, H. Fung, L. Li, & J. Woo (Eds.). Successful aging: Asian perspectives. Springer. Löckenhoff, C.E., & Rutt, J.L. (2015). Age differences in time perceptions and their implications for decision making across the lifespan. In T. Hess, J. Strough, & C.E. Löckenhoff (Eds.). Aging and decision making: Empirical and applied perspectives. Elsevier. Mendle, J., Moore, S.R., Briley, D. & Harden K.P. (2015). Puberty, socioeconomic status in girls: evidence for gene x environment interactions. Clinical Psychological Science. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1177/2167702614563598 Reyna, V.F., Brainerd, C.J. -

ED 315 663 CE 054 810 AUTHOR Fellenz, Robert A.; Conti, Gary J. TITLE Learning and Reality

DOCUMENT RESUM7, ED 315 663 CE 054 810 AUTHOR Fellenz, Robert A.; Conti, Gary J. TITLE Learning and Reality: Reflections on Trends in Adult Learning. information Series No. 336. INSTITUTION ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education, Columbus, Ohio. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Re5:earch and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 89 CONTRACT PI88062005 NOTF 44p. AVAILABLE FROMPublications Office, Center on Education and Training for Employment, 1900 Kenny Road, Columbus, OH 43210-1090 (order no. IN336: $5.25). PUB TYPE Information Analyses - ERIC Information Analysis Products (071) EDRS PRICE MF01/Prn2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; *Adult Learning; *Adult Students; Cognitive Processes; *Cognitive Psychology; Cognitive Style; Critical Thinking; Cultural Context; Educational Research; Educational Trends; *Learning Strategies; Memory; Metacognition; Participatory Research; Social Action; *Social Environment ABSTRACT The focus of thc, adult education field is shifting to adult learning. Current trends are the continued development of the concept: of andragogy and self-directed learning, increased emphasis on learning how to learn, and real-life learning. Cognitive psycholo,j is influencing work in adult learning. The concept of intelligence as it relates to adults is moving avay from the notion of IQ toward a recogn-it4.on that intelligence has multiple aspects. Application of the concept of learning style has been Hindered by confusion over terminology and lack of appropriate measurement instruments fc.1 adults. The teaching of learning strategies to adults tends to emphasize metacognition, memory, and ixtivation. Critical thinking is becoming more important in an environment complicated by an in_ormation explosion and rapid social and technological change. The influence of the social environment and culture upon learning is also being examined.