Dynamics of Youth and Violence: Findings from Rubkona County, Unity State, South Sudan 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

DRC DDG South Sudan Organogram 2016

Nhialdiu Payam Rubkona County // Unity // South Sudan Rapid Site Assessment GPS N 29.68332 // E 09.02619 April 2019 CURRENT CONTEXT LOCATION The DRC RovingCCCM team covers priority Beyond Bentiu Response (BBR) counties within Unity State; Rubkona, Guit and Koch. The team carries out CCCM activities using an area based approach, working through the CCCM cluster to disseminate information. Activities in Nhialdiu on 13th and 14th March 2019 included a multi-sector needs assessment in the area, analysis of displacement situation, mapping of structures and services and meeting with community representatives. For more information, contact Anna Salvarli [email protected] and Ezekiel Duol [email protected] COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP STRUCTURE TOTAL MEMBERS: 25 13 Female 12 Male SITE POPULATION & DISPLACEMENT CONTEXT HUMANITARAIN ACTORS STATE Unity State There are 5 humanitarian actors whose services are accessed in Nhialdiu Payam from the surrounding villages with COUNTY Rubkona County inadequate services. There have been decreased static humanitarian intervention due to insecurity incidents in 2018 in the area. The key services provided and noted were the following: PAYAM Nhialdiu Payam POPULATION 3,262 HHs , 15,036 individuals (IOM DTM March 2019) SITE TYPE Spontaneous returnees (integrated with host community) CCCM DRC (roving team from Bentiu) SITE MANAGER Self managed EDUCATION Mercy Corps (standards 1 to 4, 201 pupils; 120 female, 81 male) FSL None (WHH food assistance) DISPLACEMENT POPULATION HEALTH CASS (National Organization) There is an estimated total of over 800 individuals returnees to Nhialdiu who came between November NUTRITION Cordaid 2018 and March 2019 as per the information given by the local authority. -

Promoting Peace and Resilience in Unity State, South Sudan

BRIEF / FEBRUARY 2021 Promoting peace and resilience in Unity state, South Sudan The town of Bentiu, located in Rubkona County, is the comprising 11,529 households.1 Although people capital of the oil-rich Unity state and is predominately living in the PoC site are provided with protection and inhabited by the Nuer people. A series of waterways and humanitarian assistance, they still face challenges swamps cover large parts of the state and these provide including economic hardship, being targeted by armed pasture in the dry season for animals belonging to Nuer groups, violent crime, revenge killings inside the PoC and Dinka pastoralists, as well as other pastoralist site, and outbreaks of disease as a result of the crowded groups from neighbouring Sudan who migrate with conditions in which they live. In July 2020, UNMISS their animals into South Sudan during dry seasons in initiated consultations about its intention to re-designate search of grazing land and water. Unity state also sits the PoC sites in the country to IDP camps and hand over on some of the largest oil deposits in South Sudan and a responsibility of these camps to the government of South considerable amount of petroleum-related activity takes Sudan. People living in the Bentiu PoC site expressed place in and around Bentiu. The production of oil has concern at this plan – while conditions inside the contributed to fuelling conflicts in the state, resulting in camp are very poor, IDPs fear the threat of violence and displacement and environmental degradation. insecurity outside the PoCs if responsibility is transferred. -

South Sudan Village Assessment Survey

IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY DATA COLLECTION: August-November 2019 COUNTIES: Bor South, Rubkona, Wau THEMATIC AREAS: Shelter and Land Ownership, Access and Communications, Livelihoods, Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies, Health, WASH, Education, Protection 1 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN CONTENTS RUBKONA COUNTY OVERVIEW 15 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 15 RETURN PATTERNS 15 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 16 KEY FINDINGS 17 Shelter and Land Ownership 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Access and Communications 17 LIST OF ACRONYMS 3 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Livelihoods 18 BACKROUND 6 Health 19 WASH 19 METHODOLOGY 6 Education 20 LIMITATIONS 7 Protection 20 WAU COUNTY OVERVIEW 8 BOR SOUTH COUNTY OVERVIEW 21 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 8 RETURN PATTERNS 8 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 21 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 9 RETURN PATTERNS 21 KEY FINDINGS 10 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 22 KEY FINDINGS 23 Shelter and Land Ownership 10 Access and Communications 10 Shelter and Land Ownership 23 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 10 Access and Communications 23 Livelihoods 11 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 23 Health 12 Livelihoods 24 WASH 13 Health 25 Protection 13 Education 26 Education 14 WASH 27 Protection 27 2 3 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN LIST OF ACRONYMS AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome -

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN COUNTRY OFFICE Rapid Response Team

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN COUNTRY OFFICE Rapid Response Team Report Location (State/County/Payam/etc): Unity/Rubkona/Nhialdiu Date of the Mission: 16-25 October 2014 1 Name & Title of Kibrom Tesfaselassie - Nutrition Specialist UNICEF Team Leader 2 Names & Titles (with 1. Elizabeth Mukheb, Child protection UNIDO – Tel No. 0927328405; [email protected] org/depart/section) 2. Hari Vinathan, Nutrition Consultant, UNICEF - Tel no. 0955492068; [email protected] of other members of 3. Luel Deng, Education officer, UNICEF - Tel no. 0955158685; [email protected] 4. Okwera Joseph Okot, Health consultant - Tel no. 0959001482; [email protected] the team 5. Paul Okullu, WASH officer, International Aids Services (IAS), Tel no. 0955963274 3 Sites visited Nhialdiu HQ, Nhialdiu payam, Rubkona County, Unity State GPS; virtually centre of Nhial-Diu:- Latitude : N 09001’19.91’’ Longitude : E 029040’45.44’’ Altitude : 428.4m Information and Data collected 4 General General information about the mission site Information Number of registered people: 40,000 based on WFP verification process for previously given registration card last July. Number of households: over 14,000 including IDPs Total number of children under five (if available): Not Applicable as there was no new registration. Total number of children under 18 years (if available): NA Humanitarian situation and needs (IDPs, last time they received support, who is in control of the area etc.): Nhialdiu is a Payam of Rubkona County consisting of 16 Bomas southwest of Bentiu town approximately 40 km away. As per WFP, this mission covers four/five Payams including IDPs, with a total of population above 40,000. -

Human Security in Sudan: the Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission

Human Security in Sudan: The Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission Prepared for the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ottawa, January 2000 Disclaimer: This report was prepared by Mr. John Harker for the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. The views and opinions contained in this report are not necessarily those of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. 1 Human Security in Sudan: Executive Summary 1 Introduction On October 26, 1999, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lloyd Axworthy and the Minister for International Co-operation, Maria Minna, announced several Canadian initiatives to bolster international efforts backing a negotiated settlement to the 43-year civil war in Sudan, including the announcement of an assessment mission to Sudan to examine allegations about human rights abuses, including the practice of slavery. There are few other parts of the world where human security is so lacking, and where the need for peace and security - precursors to sustainable development - is so pronounced. Canada's commitment to human security, particularly the protection of civilians in armed conflict, provides a clear basis for its involvement in Sudan and its support for the peace process. Charm Offensive, or Signs of Progress? Following the visit to Khartoum of an EU Mission, a political dialogue was launched by the European Union on November 11 1999. The EU was of the view that there has been sufficient progress in Sudan to warrant a renewed dialogue. In this view, there has been a positive change, and it is necessary to encourage the Sudanese, and push them further where there is need. -

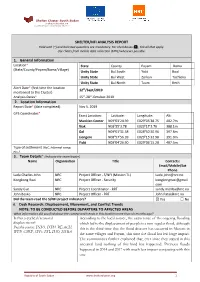

Shelter/Nfi Analysis Report 1

Shelter Cluster South Sudan sheltersouthsudan.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER/NFI ANALYSIS REPORT Field with (*) and italicized questions are mandatory. For checkboxes (☐), tick all that apply. Use charts from mobile data collection (MDC) wherever possible. 1. General Information Location* State County Payam Boma (State/County/Payam/Boma/Village) Unity State Bul South Yidit Bool Unity State Bul West Zorkan Tochloka Unity State Bul North Taam Kech Alert Date* (first time the location 12th/Sept/2019 mentioned to the Cluster) Analysis Dates* 15th-28th-October-2019 2. Location Information Report Date* (date completed) Nov 5, 2019 GPS Coordinates* Exact Location: Latitude: Longitude: Alt: Mankien Center N09003’24.99 E029005’38.75 402.7m Riak N08055’3.78 E029017’3.70 388.1m Gol N09001’31.38 E028050’40.96 397.8m Liengere N08057’56.39 E029015’32.98 391.0m Yidit N09004’26.90 E029006’15.20 407.5m Type of settlement (PoC, informal camp, etc.) 3. Team Details* (Indicate the team leader) Name Organisation Title Contacts: Email/Mobile/Sat Phone Ladu Charles John NRC Project Officer - S/NFI (Mission TL) [email protected] Kongkong Ruei NRC Project Officer - Security kongkongruei@gmail. com Sandy Gur NRC Project Coordinator - RRT [email protected] John Bosko NRC Project Officer - RRT [email protected] Did the team read the S/NFI project indicators? ☒ Yes ☐ No 4. Desk Research: Displacement, Movement, and Conflict Trends NOTE: TO BE CONDUCTED BEFORE DEPARTURE TO AFFECTED AREAS What information did you find about the context and trends in this location more than six months ago? Is this a cyclical/seasonal According to the local source, the occurrence of the ongoing flooding displacement? which led to the displacement of people is a non-regular flood, although Possible sources: INSO, DTM, REACH, this is the third time that the flood disaster has occurred in Mayom in WFP, CSRF, SFPs, FSL IMO, HSBA the same villages and Payam, this time the flood has left huge impact. -

Protecting Civilians from Unexploded Ordinance Through Community Engagement and Humanitarian Coordination in Rubkona County, Unity State

Protecting Civilians from Unexploded Ordinance through Community Engagement and Humanitarian Coordination in Rubkona County, Unity State their plots. Thoan, a settlement comprised of approximately 30 households, is located in close proximity to the bridge between Rubkona and Bentiu towns, and served as a strategic military area where government soldiers were stationed during the war. Currently, the barracks are abandoned and returnees from Sudan and Uganda have been moving back into the area, taking advantage of the abandoned infrastructure and the proximity of the river to enable agricultural. In April 2020, NP learned that inter-communal violence and instances of cattle raiding had been disturbing the lives of civilians in the county. Observing that only a few NGOs had interacted with the communities in Thoan, NP’s Beyond Photo: UXO in Thoan/Unity State, South Sudan/2020/NP Bentiu Response (BBR) team conducted a patrol in Thoan to establish a relationship with the When South Sudan descended into civil war in late returnees and assess protection concerns as the 2013, Unity State became a hotspot for hostilities newly formed settlement was also in close with heavy weapons used by all parties to the proximity to a cattle camp. While speaking to a conflict. By the time the signing of the Revitalized female community member who was occupying an Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the abandoned metal corrugated container, during a Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) halted the patrol, the BBR team noticed a pile of bullet heavy fighting in late 2018, large territories of casings beside her shelter. -

Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014

IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014 Important: - IRNA Report should include secondary data collected by all stakeholders and jointly analyzed - IRNA Report should also include community level assessment analysis by clusters and then jointly analyzed by all stakeholders - Report should adequately cover the de-briefing analysis of assessment team leaders - This report should be produced within two days after the IRNA taking place 1 IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Situation Overview (use the secondary information as well as the information gathered under the ‘Generalist’ section of the IRNA questionnaire. Map Drivers of Crisis and underlying factors Place map of affected area if available Conflict has spread across South Sudan following an alleged coup attempt three weeks ago in Juba. Among the states directly affected by the crisis is Unity State which neighbours Warrap State to the East. An influx of Internally Displaced People (IDPs) into Warrap’s Twic County has steadily increased since the last week of December Affected population: 2013. Most of those IDPs have been directly attacked or been caught (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) up in the cross fire during the fighting that has ensued in Unity State, while some have run out of seer fear. Displaced population: (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) Scope of crisis and humanitarian profile Most of the displaced are from Mayom County in Unity State, while 3,215 individuals some have been displaced from as far as Bentiu town the Unity State with possible increase in coming days capital itself, in Rubkona County. -

The War(S) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace

Conflict Research Programme The War(s) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace Flora McCrone in collaboration with the Bridge Network About the Authors Flora McCrone is an independent researcher based in East Africa. She has specialised in research on conflict, armed groups, and political transition across the Horn region for the past nine years. Flora holds a master’s degree in Human Rights from LSE and a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Durham University. The Bridge Network is a group of eight South Sudanese early career researchers based in Nimule, Gogrial, Yambio, Wau, Leer, Mayendit, Abyei, Juba PoC 1, and Malakal. The Bridge Network members are embedded in the communities in which they conduct research. The South Sudanese researchers formed the Bridge Network in November 2017. The team met annually for joint analysis between 2017-2020 in partnership with the Conflict Research Programme. About the Conflict Research Programme The Conflict Research Programme is a four-year research programme hosted by LSE IDEAS, the university’s foreign policy think tank. It is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Our goal is to understand and analyse the nature of contemporary conflict and to identify international interventions that ‘work’ in the sense of reducing violence or contributing more broadly to the security of individuals and communities who experience conflict. © Flora McCrone and the Bridge Network, February 2021. This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Following the Thread: Arms and Ammunition Tracing in Sudan and South Sudan

32 Following the Thread: Arms and Ammunition Tracing in Sudan and South Sudan By Jonah Leff and Emile LeBrun Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2014 First published in May 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Tania Inowlocki Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-9700897-1-1 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 32 Contents List of boxes, figures, maps, and tables .......................................................................................................................... 5 List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Republic of South Sudan

Republic of South Sudan Situation Report #102 on Cholera in South Sudan As at 23:59 Hours, 5 January 2017 Situation Update Cholera outbreaks have been confirmed in 9 (32%) of 28 states countrywide. The affected states include Imatong, Eastern Lakes, Jubek, Terekeka, Jonglei, Western Bieh, Northern Liech, Southern Liech; and Eastern Nile (Table 1 and Figure 1.0). In Southern Liech, one case from Ganyliel was confirmed in week 52 of 2016. Suspect cholera cases were reported in Mayendit and Ayod but were not confirmed (Table 4). Cumulatively 146 (35.7 %) of the samples tested positive for Vibrio Cholerae inaba in the National Public Health Laboratory as of 5 January 2017 (Table 3). Table 1: Summary of cholera cases reported in South Sudan as of 5 January 2017 Highlights in week 52 of 2016: 1. A total of 55 cases reported from Bentiu PoC in week 52 of 2016; compared to 101 cases in week 51 of 2016 (Table 1, Figure 1.1). 2. One cholera case from Ganyliel, Panyijiar confirmed as Vibrio cholerae inaba on 3 Jan 2017 (Table 3). 3. Resurgence of cholera in UN House PoC with 6 cases confirmed in week 52 of 2016 (Table 1 and Table 3). 4. Overall; active transmission is ongoing in Northern Liech and Southern Liech with case resurgence in UN House PoC. In Northern Liech state, 835 cholera cases including 22 confirmed cases and nine deaths (CFR 1.08%) were reported in Bentiu Town/PoC since 29 September 2016. The cholera taskforce, chaired by MoH and constituted by Health and WASH cluster partners is coordinating the response.