Philippines 2018 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drug Recycling' Officers in the Recycling of for Operations (DRDO) in Cen- Leged Involvement in Illegal Seized Illegal Drugs

MDM MONday | SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 P3 TIT FOR TAT Go wants some US senators banned from PH over de Lima Senator Christopher Lawrence Go on Saturday said he will suggest to President Rodrigo Duterte an equal retaliatory action against US senators who want to ban Philippine government officials from their country for their involvement in the detention of Senator Leila de Lima. “I will suggest to President Duterte to ban American legislators from entering our country for interfering in our internal affairs. These senators think they know better than us in governing ourselves,” Go said. Significantly, the senator made the statement in his speech at the 118th Balangiga Day Commemoration in Balangiga, Eastern Samar on Saturday, September 28. The Balangiga encounter was a successful surprise attack carried out by Filipino fighters against US troops during the Philippine-American War. It is considered by historians as one of the greatest displays of the bravery of the Filipinos fighting for their freedom. Commenting on news that a US Senate panel had approved an amendment in an appropriations bill that will ban Philippine government officials involved in the detention of de Lima, Go had choice words for the US senators: “Nakakaloko kayo.” “I condemn this act by a handful US senators… It is an affront to our sovereignty and to our ability to govern ourselves. It unduly pressures our independent courts and disrespects the entire judicial process of the Philippines by questioning its competence,” he said. Go said the US senators who proposed the initiative must themselves also be banned from the Philippines. -

Of Auxiliary Forces and Private Armies: Security Sector Governance (SSG) and Conflict Management in Maguindanao, Mindanao

The RSIS Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed in this publication are entirely those of the author(s), and do not represent the official position of RSIS. If you have any comments, please send them to [email protected]. Unsubscribing If you no longer want to receive RSIS Working Papers, please click on “Unsubscribe” to be removed from the list. No. 267 Of Auxiliary Forces and Private Armies: Security Sector Governance (SSG) and Conflict Management in Maguindanao, Mindanao Maria Anna Rowena Luz G. Layador S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Singapore 16 January 2014 This working paper is an outcome of a research initiative on the theme ‘Responding to Internal Crises and Their Cross Border Effects’ led by the Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). The initiative was organised around related sub-themes, each of which was addressed by a research group comprising selected scholars from across Southeast Asia. This paper emerged from work by the research group focused on ‘Bridging Multilevel and Multilateral Approaches to Conflict Prevention and Resolution: Security Sector Governance and Conflict Management in Southeast Asia’. This project was supported by the MacArthur Foundation’s Asia Security Initiative (ASI). For more information on the ASI, please visit http://www.asicluster3.com. i About RSIS The S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) was established in January 2007 as an autonomous School within the Nanyang Technological University. Known earlier as the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies when it was established in July 1996, RSIS‟ mission is to be a leading research and graduate teaching institution in strategic and international affairs in the Asia Pacific. -

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

Philippines: Information on the Barangay and on Its Leaders, Their

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 19 September 2003 PHL41911.E Philippines: Information on the barangay and on its leaders, their level of authority and their decision-making powers (1990-2003) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Ottawa A Cultural Attache of the Embassy of the Philippines provided the attached excerpt from the 1991 Local Government Code of the Philippines, herein after referred to as the code, which describes the role of the barangay and that of its officials. As a community-level political unit, the barangay is the planning and implementing unit of government policies and activities, providing a forum for community input and a means to resolve disputes (Republic of the Philippines 1991, Sec. 384). According to section 386 of the code, a barangay can have jurisdiction over a territory of no less than 2,000 people, except in urban centres such as Metro Manila where there must be at least 5,000 residents (ibid.). Elected for a term of five years (ibid. 14 Feb. 1998, Sec. 43c; see the attached Republic Act No. 8524, Sec. 43), the chief executive of the barangay, or punong barangay enforces the law and oversees the legislative body of the barangay government (ibid. 1991, Sec. 389). Please consult Chapter 3, section 389 of the code for a complete description of the roles and responsibilities of the punong barangay. In addition to the chief executive, there are seven legislative, or sangguniang, body members, a youth council, sangguniang kabataan, chairman, a treasurer and a secretary (ibid., Sec. -

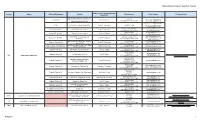

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

Ethnic and Religious Conflict in Southern Philippines: a Discourse on Self-Determination, Political Autonomy, and Conflict Resolution

Ethnic and Religious Conflict in Southern Philippines: A Discourse on Self-Determination, Political Autonomy, and Conflict Resolution Jamail A. Kamlian Professor of History at Mindanao State University- ILigan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT), ILigan City, Philippines ABSTRACT Filipina kini menghadapi masalah serius terkait populasi mioniritas agama dan etnis. Bangsa Moro yang merupakan salah satu etnis minoritas telah lama berjuang untuk mendapatkan hak untuk self-determination. Perjuangan mereka dilancarkan dalam berbagai bentuk, mulai dari parlemen hingga perjuangan bersenjata dengan tuntutan otonomi politik atau negara Islam teroisah. Pemberontakan etnis ini telah mengakar dalam sejarah panjang penindasan sejak era kolonial. Jika pemberontakan yang kini masih berlangsung itu tidak segera teratasi, keamanan nasional Filipina dapat dipastikan terancam. Tulisan ini memaparkan latar belakang historis dan demografis gerakan pemisahan diri yang dilancarkan Bangsa Moro. Setelah memahami latar belakang konflik, mekanisme resolusi konflik lantas diajukan dalam tulisan ini. Kata-Kata Kunci: Bangsa Moro, latar belakang sejarah, ekonomi politik, resolusi konflik. The Philippines is now seriously confronted with problems related to their ethnic and religious minority populations. The Bangsamoro (Muslim Filipinos) people, one of these minority groups, have been struggling for their right to self-determination. Their struggle has taken several forms ranging from parliamentary to armed struggle with a major demand of a regional political autonomy or separate Islamic State. The Bangsamoro rebellion is a deep- rooted problem with strong historical underpinnings that can be traced as far back as the colonial era. It has persisted up to the present and may continue to persist as well as threaten the national security of the Republic of the Philippines unless appropriate solutions can be put in place and accepted by the various stakeholders of peace and development. -

The State of Human Rights in the Philippines 2012

The State of Human Rights in the Philippines in 2012 AHRC-SPR-009-2012 PHILIPPINES: The State of Human Rights in 2012 Strong rights, No remedy The discourse on protection of rights this year in the Philippines has been unique. Rights that were not previously recognized are now recognized; public officials and security officers, who could not be prosecuted even in one’s imagination, were prosecuted; and victims and their families, who often chose to keep silent due to fear and oppression, now seek remedies demanding their rights. This phenomenon is taking many forms, offering enormous prospects for the protection of rights. To cite a few examples: the conviction of Renato Corona, former chief justice, following a widely publicized impeachment trial, has given rise to the discourse on judicial accountability. The prosecution of former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and her former General Jovito Palparan, who is now a fugitive, for corruption and abduction of student activists respectively, has given rise to the prospect that public and security officials who breached public trust and committed human violations in the past, can now be prosecuted. Also, that a group of people—particularly the Muslims in the south—who had been subject to systematic and widespread subjugation for many decades, would now agree on creating a political entity under the same sovereignty which it fought against, is further evidence of confidence in the government. The Bangsamoro Framework Agreement (BFA), signed between the rebel group and the government on October 15, 2012, is a historic development, which offers the prospect, not only of peace emerging from decades of conflict in Mindanao, but also of the building of democratic institutions. -

Judicial Tenure and the Politics of Impeachment

C International Journal for Court Administration International Association For copywriteart.pdf 1 12/20/17 8:30 AM Vol.CourtM Administration 9 No. 2, July 2018 ISSNY 2156-7964 URL: http://www.iacajournal.org CiteCM this as: DOI 10.18352/ijca.260 Copyright: MY CY JudicialCMY Tenure and the Politics of Impeachment - 1 ComparingK the United States and the Philippines David C. Steelman2 Abstract: On May 11, 2018, Maria Lourdes Sereno was removed from office as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines. She had been a vocal critic of controversial President Rodrigo Duterte, and he had labeled her as an “enemy.” While she was under legislative impeachment investigation, Duterte’s solicitor general filed aquo warranto petition in the Supreme Court to challenge her right to hold office. The Supreme Court responded to that petition by ordering her removal, which her supporters claimed was politically-motivated and possibly unconstitutional. The story of Chief Justice Sereno should give urgency to the need for us to consider the proposition that maintaining the rule of law can be difficult, and that attacks on judicial independence can pose a grave threat to democracy. The article presented here considers the impeachment of Chief Justice David Brock in the American state of New Hampshire in 2000, identifying the most significant institutional causes and consequences of an event that presented a crisis for the judiciary and the state. It offers a case study for the readers of this journal to reflect not only on the removal of Chief Justice Sereno, but also on the kinds of constitutional issues, such as judicial independence, judicial accountability, and separation of powers in any democracy, as arising from in conflicts between the judiciary and another branch of government. -

Asa350071998en.Pdf

amnesty international PHILIPPINES Marlon Parazo, deaf and mute, faces execution August 1998 AI INDEX: ASA 35/07/98 DISTR: SC/CO/GR Marlon Parazo, aged 27, was born into poverty in the province of Nueva Ecija, Philippines. Profoundly deaf and mute since birth, he is effectively isolated from ordinary contact with society and is only able to communicate with his family through touch and gestures. He has never learned any official form of sign language and is unable to read or write, having received only two months’ schooling at the age of seven. In the Philippines, there is little or no provision for special schooling for the disabled. In March 1995 Marlon Parazo was convicted of rape and attempted homicide and was sentenced to death, despite the fact that the trial court made no attempt to ensure that he understood the proceedings against him. Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which the Philippines is a party, states that the defendant has the right to be informed “in detail in a language which he understands of the nature and cause of the charge against him” and “to have the free assistance of an interpreter if he cannot understand or speak the language used in court”. During the trial no one - not even Marlon Parazo’s court-appointed defence lawyer - made any reference to his disabilities. Despite this violation of his right to a fair trial, the Supreme Court confirmed his death sentence in May 1997. Marlon Parazo’s case has now been taken up by the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG), a leading association of human rights lawyers. -

Philippines's Constitution of 1987

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 constituteproject.org Philippines's Constitution of 1987 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 Table of contents Preamble . 3 ARTICLE I: NATIONAL TERRITORY . 3 ARTICLE II: DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLES AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES . 3 ARTICLE III: BILL OF RIGHTS . 6 ARTICLE IV: CITIZENSHIP . 9 ARTICLE V: SUFFRAGE . 10 ARTICLE VI: LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT . 10 ARTICLE VII: EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT . 17 ARTICLE VIII: JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT . 22 ARTICLE IX: CONSTITUTIONAL COMMISSIONS . 26 A. COMMON PROVISIONS . 26 B. THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION . 28 C. THE COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS . 29 D. THE COMMISSION ON AUDIT . 32 ARTICLE X: LOCAL GOVERNMENT . 33 ARTICLE XI: ACCOUNTABILITY OF PUBLIC OFFICERS . 37 ARTICLE XII: NATIONAL ECONOMY AND PATRIMONY . 41 ARTICLE XIII: SOCIAL JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS . 45 ARTICLE XIV: EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ARTS, CULTURE, AND SPORTS . 49 ARTICLE XV: THE FAMILY . 53 ARTICLE XVI: GENERAL PROVISIONS . 54 ARTICLE XVII: AMENDMENTS OR REVISIONS . 56 ARTICLE XVIII: TRANSITORY PROVISIONS . 57 Philippines 1987 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 • Source of constitutional authority • General guarantee of equality Preamble • God or other deities • Motives for writing constitution • Preamble We, the sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty God, in order to build a just and humane society and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promote the common good, conserve and develop our patrimony, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law and a regime of truth, justice, freedom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and promulgate this Constitution. -

Sandiganbayan Quezon City

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Sandiganbayan Quezon City SIXTH DIVISION PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, SB-16-CRM-0334 Plaintiff, For: Violation of Section 7(d) of R.A. No. 6713 SB-16-CRM-0335 For: Direct Bribery - versus - Present: FERNANDEZ, SJ, JL, ANGELITO DURAN SACLOLO, JR., Chairperson BT AL. MIRANDA, J". and Accused. VIVERO, J. Promulgated: J tf X- -X DECISION FERNANDEZ, SJ, J. Accused Angelito Duran Saclolo, Jr. and Alfredo G. Ortaleza stand charged for violation of Article 210 of the Revised Penal Code^ and of Section 7(d) of R.A. No. 6713,2 for demanding and accepting the amount of PhP300,000.00 / from Ma. Linda Moya of Richworld Aire and Technologie&V 'Republic Act No. 3815 2 Code ofConduct and Ethical Standardsfor Public Officials and Employees, Februaiy 20, 1989 DECISION People vs. Saclolo et at. Criminal Case Nos. SB-16-CRM-0334 to 0335 Page 2 of63 X X Corporation (Richworld), in consideration for the immediate passage of a Sangguniang Panlungsod Resolution authorizing the construction of Globe Telecoms cell sites in Cabanatuan City. The Information in SB'16-CRM'0334 reads: For: Violation ofR.A. No. 6713, Sec. 7(d) That on April 10, 2013 or sometime prior or subsequent thereto, in the City of Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija, Philippines and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the accused, Angelito Duran Saclolo, Jr. and Alfredo Garcia Ortaleza, both public officers, being then a Member of the Sangguniang Panlungsod and concurrent Chairman of the Committee on Transportation and Communications and Secretaiy to the Sangguniang Panlungsod, respectively, of Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija, while in the performance of their official functions, committing the offense in relation to their office and taking advantage of their official positions, conspiring and confederating with one another, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and criminally accept the amount of Three Hundred Thousand Pesos (P300,000.00) from Ma. -

Chapter 3 Socio Economic Profile of the Study Area

CHAPTER 3 SOCIO ECONOMIC PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA 3.1 SOCIAL CONDITIONS 3.1.1 Demographic Trend 1) Population Trends by Region Philippine population has been continuously increasing from 48.1million in 1980, 76.3 million in 2000 to 88.5million in 2007 with 2.15% of annual growth rate (2000-2007). Population of both Mindanao and ARMM also showed higher increases than national trend since 2000, from 18.1 in 2000 to 21.6 million in 2007 (AAGR: 2.52%), and 2.9 in 2000 to 4.1million in 2007 (AAGR: 5.27%), respectively. Population share of Mindanao to Philippines and of ARMM to Mindanao significantly increased from 23.8% to 24.4% and 15.9% to 24.4%, respectively. 100,000,000 90,000,000 Philippines Mindanao 80,000,000 ARMM 70,000,000 60,000,000 50,000,000 40,000,000 30,000,000 20,000,000 10,000,000 0 1980 1990 1995 2000 2007 Year Source: NSO, 2008 FIGURE 3.1.1-1 POPULATION TRENDS OF PHILIPPINES, MINDANAO AND ARMM Population trends of Mindanao by region are illustrated in Figure 3.1.1-2 and the growth in ARMM is significantly high in comparison with other regions since 1995, especially from 2000 to 2007. 3 - 1 4,500,000 IX 4,000,000 X XI 3,500,000 XII XIII ARMM 3,000,000 2,500,000 2,000,000 1,500,000 1,000,000 1980 1990 1995 2000 2007 year Source NSO, 2008 FIGURE 3.1.1-2 POPULATION TRENDS BY REGION IN MINDANAO As a result, the population composition within Mindanao indicates some different features from previous decade that ARMM occupies a certain amount of share (20%), almost same as Region XI in 2007.