Breastfeeding: Contradictory Messages and Meanings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Areola-Sparing Mastectomy: Defining the Risks

COLLECTIVE REVIEWS Areola-Sparing Mastectomy: Defining the Risks Alan J Stolier, MD, FACS, Baiba J Grube, MD, FACS The recent development and popularity of skin-sparing to actual risk of cancer arising in the areola and is pertinent mastectomy (SSM) is a likely byproduct of high-quality to any application of ASM in prophylactic operations. autogenous tissue breast reconstruction. Numerous non- 7. Based on clinical studies, what are the outcomes when randomized series suggest that SSM does not add to the risk some degree of nipple-areola complex (NAC) is preserved of local recurrence.1–3 Although there is still some skepti- as part of the surgical treatment? cism,4 SSM has become a standard part of the surgical ar- mamentarium when dealing with small or in situ breast ANATOMY OF THE AREOLA cancers requiring mastectomy and in prophylactic mastec- In 1719, Morgagni first observed that there were mam- tomy in high-risk patients. Some have suggested that SSM mary ducts present within the areola. In 1837, William also compares favorably with standard mastectomy for Fetherstone Montgomery (1797–1859) described the 6 more advanced local breast cancer.2 Recently, areola- tubercles that would bare his name. In a series of schol- sparing mastectomy (ASM) has been recommended for a arly articles from 1970 to 1974, William Montagna and similar subset of patients in whom potential involvement colleagues described in great detail the histologic anat- 7,8 by cancer of the nipple-areola complex is thought to be low omy of the nipple and areola. He noted that there was or in patients undergoing prophylactic mastectomy.5 For “confusion about the structure of the glands of Mont- ASM, the assumption is that the areola does not contain gomery being referred to as accessory mammary glands glandular tissue and can be treated the same as other breast or as intermediates between mammary and sweat 9 skin. -

What You Need to Know to Successfully Start Breastfeeding Your Baby

BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW TO SUCCESSFULLY START BREASTFEEDING YOUR BABY Northpoint Pediatrics supports breastfeeding for our patients and offers a full-time lactation expert to help. Breastfeeding is a natural way to feed your baby, but it does not always come easily as mom and baby learn how. Start with this brochure to learn how to get started, how to keep breastfeeding when you return to work, and the best breastfeeding diet. Getting started Don’t panic if your newborn seems to have trouble latching or staying on your nipple. Breastfeeding requires patience and lots of practice. Ask a nurse for help and request a visit from the hospital or Northpoint lactation consultant. Breastfeeding is going well if: Call your doctor if: □ Your baby is breastfeeding at least eight □ Your baby is having fewer than six wet diapers times in 24 hours a day by the sixth day of age □ Your baby has at least six wet diapers □ Your baby is still having meconium (black, every 24 hours tarry stools) on the fourth day of age or is □ Your baby has at least four bowel having fewer than four stools by the sixth day movements every 24 hours of age □ You can hear your baby gulping or □ Your milk supply is full but you don’t hear swallowing at feeds your baby gulping or swallowing frequently during breastfeeding □ Your breasts feel softer after a feed □ Your nipples are painful throughout the feed □ Your nipples are not painful □ Your baby seems to be breastfeeding □ Breastfeeding is an enjoyable experience “all the time” □ You don’t feel that your breasts are full and excreting milk by the fifth day □ Your baby is a “sleepy, good baby” and is hard to wake for feedings NORTHPOINTPEDS.COM — NOBLESVILLE — INDIANAPOLIS — 317-621-9000 1 BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW TO SUCCESSFULLY START BREASTFEEDING YOUR BABY Are you nursing correctly? Pumping at work A checklist from the American Academy of Pediatrics. -

Recognizing When Things Are Are Things Heading South? Well, It's All About the Clues

Investigating for Low Milk Supply Objectives Recognizing When Things are 1. Differentiate the three main categories of milk production problems. 2. List at least 3 risk factors for lactation problems in the early postpartum 3. Relate the importance of current pregnancy history to lactation capability 4. Explain the impact of infant suck on What’s going on? maternal milk production Lisa Marasco MA, IBCLC, FILCA [email protected] © 2019 ~No disclosures~ Are things Gathering good clues Start by listening to mom’s story heading south? Is there really a problem? No Reassure, educate Yes Take a detailed history Risk factors for delays Breastfeeding Management Yes Further Observations Infant assessment Well, it’s all Feeding assessment about the clues Maternal Assessment Differentiate delayed, primary and/or secondary causes Early weight loss Start Here → Is baby getting enough? >7%? >10%? Vag Lots of smaller stools OR Delivery Less often but blow-outs C-sect Once milk comes in, baby Delivery should start to gain 30- 45g/day in the first 1-2 mo Flaherman, et al. (2015). Early weight loss nomograms for exclusively breastfed newborns. Pediatrics How does baby look and act? Use day 2 weight as baseline for % loss - Noel-Weiss 2011 © Lisa Marasco 2019 1 Investigating for Low Milk Supply APPROXIMATE weight gain for babies in the 25th to 75th percentiles Week 1 Initially, loses up to 7-10% of birth weight (Note: weight at 24 hours may be more accurate true birth weight) Week 2 Regains to birth weight, or has started to gain 1oz (30g) per day WHO Velocity Weeks 3 & 4 Gains 8-9 oz (240-270g) per week Growth Charts Month 2 Gains 7-10 oz (210-300g) per week Month 3 Gains 5-7oz (150-210g) per week From: Riddle & Nommsen-Rivers (2017). -

Tongue Ties & Lip Ties

TONGUE TIES & LIP TIES: WHAT PARENTS NEED TO KNOW WHAT IS A WHAT IS A TONGUE TIE? LIP TIE? A tongue tie occurs when the thin membrane Many babies with a tongue under the baby’s tongue (the lingual tie, also have an abnormally frenulum) restricts the movement tight membrane attaching of the tongue. All babies are born their upper lip to their with some of this tissue, but for upper gums (the labial approximately 5-12% of new- frenulum). This is called borns, it is so tight that they a lip tie. Babies with cannot move their tongues a lip tie often have freely. This can affect their difficulty flanging their ability to breastfeed and lips properly to feed and lead to poor latch, nipple cannot create a proper seal pain and trauma, decreased at the breast. This can cause milk intake and a decline in them to take in excess air milk supply over time. The during breastfeeding, which often medical term for tongue tie is makes these babies gassy and fussy. “ankyloglossia” and studies show the defect is hereditary. The above photos are only examples of ties - NOT ALL TIES LOOK THE SAME. It takes an experienced provider to thoroughly investigate tongue function and symptoms associat- ed with each tie, and to take into account the variations of its clinical appearance. HOW AND WHY DO TIES AFFECT BREASTFEEDING? The mobility of the tongue is very important during breastfeeding, both for the mother and the baby. A baby with a tied tongue may not be able to latch deeply onto the breast, past the nipple onto the areola. -

What to Do If Your Breasts Are Swollen

What to Do If Your Breasts Are Swollen Breast swelling is a common but temporary problem that usually starts during the first few days after birth and resolves within a day or two. The swelling may be from the fluid shifts associated with pregnancy, labor and delivery or it may be from the increase in your milk production. These two different types of breast swellings look the same but you need a different technique for each to soften the breast and make it easier for your baby to breastfeed effectively and comfortably. Swollen breasts within the first three days are almost certainly from extra retention of water in your tissues. Hormonal shifts after delivery, intravenous fluids and side effects of medications given during labor can cause both your ankles and breasts to swell, which can flatten your nipples. If water retention is the cause of the swelling, pumping your breasts may make the problem worse. Imagine if you had a “fat lip” from an injury. The last thing you would want to do is apply suction. That would only draw more fluid into your lips and increase the swelling. Swelling in the tissue from extra water can also get in the way of milk flow when the milk increases between the second and fourth day. That’s why it is a good idea to reduce the swelling from postpartum edema before pumping. Natural breastfeeding is a great technique to help keep swelling to a minimum because the positioning helps gravity work to bring the fluid back towards the 1 body rather than down towards the nipple. -

Breastfeeding Myths!

Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments Breastfeeding Myths Many Women do not produce enough milk. Not True! But the baby may not be getting the milk mom has available. For more information, call Mary at (309) 525-0194. It is normal for breastfeeding to hurt. Not True! If it hurts, baby is not latched well. Baby will not get enough milk if the latch is not good, so do not tolerate pain. For more information, call Mary at (309) 525-0194. There is not enough milk in the first 3-4 days to satisfy baby. Wrong! The first milk produced is colostrum. It is similar to a power bar for athletes. It is measured in drops or teaspoons, not ounces. Your body knows how big your baby is before you do, and it knows how much to produce. Colostrum is perfect for the baby’s “unfinished” digestive system. A baby who is latched to the breast correctly will get all the milk he needs. A baby will need to be at breast for 5, 10, 20 minutes on each side to make sure they get enough to eat, and not cause nipple pain. False. Limiting time at breast will not fix a bad latch, which is what causes pain. Feeding for hours at a time will not fix a bad latch which is what limits milk available to baby. A baby who is latched well and transferring milk will not be at the breast for hours at a time. A mother should wash her nipples before feeding. -

Pregnancy-Associated Hyperkeratosis of the Nipple a Report of 25 Cases

OBSERVATION Pregnancy-Associated Hyperkeratosis of the Nipple A Report of 25 Cases H. William Higgins, MD; Jennifer Jenkins, MD, MPH; Thomas D. Horn, MD, MBA; George Kroumpouzos, MD, PhD Importance: Reported physiologic nipple changes in symptomatic aggravation only during pregnancy or breast- pregnancy do not include hyperkeratosis and are ex- feeding. The lesions persisted post partum in 22 pa- pected to resolve or improve post partum. Hyperkerato- tients (88%). Histopathologic features were conspicu- sis of the nipple and/or areola can develop in the con- ous orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, with papillomatosis text of inflammatory diseases (such as atopic dermatitis), and acanthosis being mild or absent. in acanthosis nigricans, as an extension of epidermal ne- vus, after estrogen treatment, and/or in nevoid hyper- Conclusions and Relevance: Pregnancy-associated hy- keratosis of the nipple and areola. We performed a clini- perkeratosis of the nipple can be symptomatic and per- copathologic analysis of cases of pregnancy-associated sist post partum. It may represent a physiologic change nipple hyperkeratosis. of pregnancy. The characteristic clinicopathologic fea- tures of this disorder allow differentiation from nevoid Observations: Twenty-five cases of pregnancy- hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola. We suggest that associated nipple hyperkeratosis identified during a 5-year this distinctive clinicopathologic entity be called preg- period (January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2012) nancy-associated hyperkeratosis of the nipple. are reported. The lesions were bilateral and involved pre- dominantly the top of the nipple. Lesions were sympto- matic in 17 patients (68%), causing tenderness or dis- JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(6):722-726. comfort, pruritus, sensitivity to touch, and/or discomfort Published online April 24, 2013. -

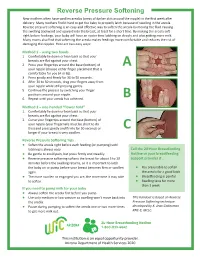

Reverse Pressure Softening New Mothers Often Have Swollen Areolas (Areas of Darker Skin Around the Nipple) in the First Week After Delivery

Reverse Pressure Softening New mothers often have swollen areolas (areas of darker skin around the nipple) in the first week after delivery. Many mothers find it hard to get the baby to properly latch because of swelling in the areola. Reverse pressure softening is an easy and effective way to soften the areola by moving the fluid causing the swelling backward and upward into the breast, at least for a short time. By making the areola soft right before feedings, your baby will have an easier time latching on deeply and also getting more milk. Many moms also find that softening the areola makes feedings more comfortable and reduces the risk of damaging the nipples. Here are two easy ways: Method 1 – using two hands 1. Comfortably lie down or lean back so that your breasts are flat against your chest. 2. Press your fingertips around the base (bottom) of A your nipple (choose either finger placement that is comfortable for you (A or B)). 3. Press gently and firmly for 30 to 50 seconds. 4. After 30 to 50 seconds, drag your fingers away from your nipple while still pressing gently. 5. Continue the process by switching your finger positions around your nipple. 6. Repeat until your areola has softened. B Method 2 – one-handed “flower hold” 1. Comfortably lie down or lean back so that your breasts are flat against your chest. 2. Curve your fingertips around the base (bottom) of your nipple (your fingernails must be short to do this) and press gently and firmly for 50 seconds or C longer if your breast is very swollen. -

Use of Medihoney® Paste Dressings by Breast-Feeding Mothers for the Management of Sore Or Cracked Nipples

MediHoney Wound and Burn Dressing Use of MediHoney® Paste Dressings by Breast-Feeding Mothers for the Management of Sore or Cracked Nipples ore and cracked nipples can be a real problem for breast-feeding mothers. This issue is one of the most common reasons moms stop breast-feeding early in their experience1. As much as 96% of breast-feeding moms report at least some nipple discomfort during S 2 the first 6 weeks after the birth of a baby . There are many possible contributors to the development of sore and cracked nipples during breast-feeding, so you should always speak to your physician, nurse and/or lactation consultant about your experiences and ask them for help and guidance in how you might decrease your discomfort. Nipple injuries can really interfere with your breast-feeding experience. The best treatment for nipple injuries is prevention! However, when they do occur, MediHoney® Wound and Burn Dressing may be used to help provide protection to the area, decrease chafing and help the injury to close. MediHoney Paste (100% Active Leptospermum Honey) is the most appropriate of the Medihoney products for this use. When using MediHoney, we recommend the following: • After nursing, gently cleanse the nipple area with a warm washcloth to remove any of the baby’s saliva. • Extrude a small amount of MediHoney from the tube and gently apply to the nipple and the areola (the colored area around the nipple) • Apply a nursing pad over the nipple area and wear a bra to help secure the pad • Just prior to nursing your baby, use a warm wet washcloth to clean off any MediHoney prior to allowing the baby to latch. -

Quick Reference Chart for Clinical Breast Examination Normal Breast Lump Change in Volume/Shape

Quick reference chart for clinical breast examination Clinical breast examination (CBE) Normal breast includes careful history-taking, visual inspection, palpation of both breasts, arm pits and root of the neck as well as educating women on breast self- examination and awareness, particularly on breast lumps. History-taking should include the following: 123 456age at menarche, marital status, parity, Normal female breasts: Note Lateral view of normal female breasts: Note Normal female breasts: Note Normal nippple Inverted nipple, horizontal age at first child birth, history of lactation similar size and shape, similar size and shape, nipples at the same similar size and shape, nipples and areola slit is a normal variation. It and breast-feeding, age at menopause, nipples at the same level, level, normal nipples, areola and skin at the same level, normal should not be diagnosed family history of breast and ovarian normal nipples, areola and nipples, areola and skin as retracted nipple as skin there is no underlying cancers in first degree relatives (mother, lump or other sign of sisters, aunts, grandmothers), history and breast cancer duration of oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), Lump treatment for infertility and tobacco use. After taking history, both breasts should be visually inspected, both in the sitting and lying down positions and with arms down and up, for any of the following: swelling, lumps, changes in size and shape, skin dimpling, skin retraction, skin thickening, 789101112skin nodules, skin ulceration, the level of Single, painless, hard lump in Single, painless, hard lump Painless, hard lump in the upper outer quadrant of the left Lobulated hard Large, lobulated hard both nipples, retraction of either nipple, the lower outer quadrant of in the lower quadrants of breast with restricted mobility. -

Tongue During

PERSPECTIVES 1211 Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.2005.077057 on 21 November 2005. Downloaded from Congenital anomalies The movements of the tongue during ....................................................................................... infant feeding have been studied by cine-radiography and more recently by ultrasound.12 13 Ultrasound reveals some Tongue tie similarities between the movements made by the baby when either breast D M B Hall, M J Renfrew or bottle feeding,14 but also some impor- tant differences.15 The tongue is pro- ................................................................................... jected further forward in breast 16 Common problem or old wives’ tale? feeding and the human nipple elon- gates during each suck in a way that an artificial teat cannot do.14 During feed- he resurgence of interest in breast tongue tie is an important issue—she ing, the artificial teat, or the nipple feeding has been accompanied by a experienced pain for many weeks while together with some breast tissue, is held Tlively debate about the significance breast feeding her first child, who fully in the mouth with the tongue of ‘‘tongue tie’’ or ankyloglossia. exhibited features said to be typical of covering the lower gum ridge. The Symptoms attributed to tongue tie tongue tie, and has since discussed this nipple is protected from damage and include nipple pain and trauma, diffi- issue widely with lactation specialists pain at the back of the baby’s mouth.16 culty in the baby attaching to the breast, and women having similar problems. The baby’s lower jaw is then elevated, frequent feeding, and uncoordinated The other (DH) accepted that ankylo- compressing the artificial teat, or the sucking. -

Naturopathic Doula Training Course

Naturopathic Doula Training Course DR. JESSICA SANGIULIANO-DUPONT, ND © Jessica Sangiuliano HELLO ¡ Doula since 2012; Naturopath since 2013 ¡ Course administrator since 2014 ¡ Practice focus is Women’s Health, Endocrinology, Fertility, Perinatal Care and Birth Services ¡ Attended over 200 births across the Dr. Jessica Dupont, ND & Birth Doula GTA (hospital, homebirth, birth center, midwives, OB/GYNs, water births, cesareans, etc.) ¡ Owner York Region Naturopathic Doulas ¡ www.yorkregiondoulas.com Course Goals You will: ¡ Learn to manage perinatal cases effectively utilizing proper assessment techniques, standard diagnostics, and treatment. ¡ Realize the importance of the spoken word as well as body language in affecting the outcome of a birth ¡ Have a good understanding of proper nutrition and supplementation during the childbearing year and beyond ¡ Learn useful, natural remedies for common perinatal concerns and issues that arise during labour/childbirth ¡ Be able to demonstrate various exercises, maneuvers, massage techniques, and acupressure points used in labour ¡ Be able to support a woman and her partner through pregnancy, a live birth and post-partum. ¡ And so much more… INTRODUCTION MODULE 1: DOULA BASICS MODULE 2: PREGNANCY MODULE 3: LABOUR/BIRTH MODULE 4: POSTPARTUM MODULE 5: BUSINESS & CASES MODULE 1 DOULA BASICS DOULA: DOULA-ing: dou-la \ doo-la “The act of , loving, “…a woman educatng experienced in respecting, listening, embracing, childbirth who advocating for, & assisting provides continuous a woman prenatally, during