Title of the Thesis: 'Hip Hop Versus Rap'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life of George Brooks Artist in Stone by Juanita Brooks 1965

The Life of George Brooks Artist in Stone by Juanita Brooks 1965 Chapter 1 BACKGROUND AND EARLY LIFE For ages the rocky promitory on the north extremity of Wales has jutted out into the sea, to be known by the early inhabitants of the area as “The Point of Ayr.” Surrounded on three sides by water, with a low, gravelly beach at low tide, it became inundated up to several feet at high tide, and a boiling, foaming torrent in storms. It was such a hazard to seafaring men that by 1700 it was marked with a small lighthouse, erected for and supported by the merchants of Chester, far down at the end of the bay, As the city of Liverpool grew in importance, this danger spot became their concern also, for their commerce was constantly threatened by the submerged rocks. During the summer of 1963, the author, her husband, William Brooks, and her daughter, Mrs. Thales A. Derrick, visited the lighthouse here at the point of Ayr and became acquainted with a man who gave them the address of the present owner of the property, Mr. H. F. Lewis. In a letter dated August 27, 1963, he said: “. The Elder Brethren of Trinity House, who did not like privately owned lighthouses, heard of the defaulting of the Port of Chester Authority & petitioned the King in 1815 to have the jurisdiction of the L. H. Placed under their auspices. This was granted by King George III. I have this document as the first of the L. H. Deeds . “Originally the keeper lived ashore at the house still known as the Lighthouse cottage. -

The Winning Entries of the 13 Annual

The United Jewish Community of the Virginia Peninsula, Inc. Presents The Winning Entries of the 13th Annual Holocaust Writing Competition for Students 2014 Beyond Courage Rescuers and Resistors of the Holocaust Special Thanks This competition is made possible through the generosity of The Sarfan/Gary S. and William M. Nachman Philanthropic Fund of the UJC Endowment Fund. In Appreciation.... Special thanks to the Holocaust Writing Competition Committee for their dedication and commitment to this annual project. Our competition final judges have been outstanding and we thank them for their time and commitment to excellence. Committee/Readers Sandy Katz, Co-chair Helaine Shinske, Co-Chair Rhoda Beckman Margo Drucker Milton Katz Elaine Nadig Linda Roesen Ruth Sacks Barbara Seligman Lucy Sukman Jayne Zilber b b b Competition Final Judges Bonnie Fay Tom Fay Dr. Linda Burgess-Getts Joan Goldman Dr. Andrew Falk The Honorable Judie Kline Dr. Paulette Molin Meera Rao Joanne K. Roos b b b Linda Molin, UJC Staff -2- The 13th Annual Holocaust Writing Competition Sponsored by The United Jewish Community of the Virginia Peninsula, Inc. and made possible with a generous grant from the Sarfan/Gary S. and William M. Nachman Philanthropic Fund of the UJC Endowment Fund. ne of the primary goals of this writing competition is to encourage young people to apply the lessons Oof history to the moral decisions they make today. Through studying the Holocaust, students explore the issues of moral courage as well as the dangers of prejudice, peer pressure, unthinking obedience to authority, and indifference. This competition provides students an opportunity to think and express themselves creatively about what they have learned. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra to Honor Legendary Composer Stanley Silverman at Annual Gala in Beverly Hills

AMERICAN FRIENDS OF THE ISRAEL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA TO HONOR LEGENDARY COMPOSER STANLEY SILVERMAN AT ANNUAL GALA IN BEVERLY HILLS Silverman will be honored at the organization’s Los Angeles gala on October 25, 2018, which will bring together entertainment, music and philanthropic notables for an evening celebrating the global impact of music LOS ANGELES, August 24, 2018 - Stanley Silverman will be honored by the American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (AFIPO), on the occasion of his 80th birthday, at their upcoming Los Angeles gala, October 25, 2018 at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills. The event will honor the life and work of the diverse Grammy and Tony nominated American composer, with a program inclusive of classical and popular music Silverman has composed for both theater and film, along with remarks by special guests. Actors Rob Morrow and Jane the Virgin star Jaime Camil will MC the event. Pianist Ory Shihor will perform alongside members of the Israel Philharmonic. Silverman joins other musical legends who have been honored by the AFIPO at their Los Angeles gala, including multi-Oscar winning composer Hans Zimmer in 2014, and conductor Zubin Mehta in 2017. “I am honored to be receiving this recognition from the AFIPO,” said Silverman, “As a passionate supporter of the organization, I am very much looking forward to the gala in October and hearing some of my important pieces played by these musicians of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.” “From the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra’s founding, by some of the best musicians across Europe, the roots of the orchestra have always been about moving the world through music. -

Introduction: the Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology

Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology 1 Mary Evelyn Tucker and John A. Grim Introduction: The Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology HIS ISSUE OF DÆDALUS brings together for the first time diverse perspectives from the world’s religious traditions T regarding attitudes toward nature with reflections from the fields of science, public policy, and ethics. The scholars of religion in this volume identify symbolic, scriptural, and ethical dimensions within particular religions in their relations with the natural world. They examine these dimensions both historically and in response to contemporary environmental problems. Our Dædalus planning conference in October of 1999 fo- cused on climate change as a planetary environmental con- cern.1 As Bill McKibben alerted us more than a decade ago, global warming may well be signaling “the end of nature” as we have come to know it.2 It may prove to be one of our most challenging issues in the century ahead, certainly one that will need the involvement of the world’s religions in addressing its causes and alleviating its symptoms. The State of the World 2000 report cites climate change (along with population) as the critical challenge of the new century. It notes that in solving this problem, “all of society’s institutions—from organized re- ligion to corporations—have a role to play.”3 That religions have a role to play along with other institutions and academic disciplines is also the premise of this issue of Dædalus. The call for the involvement of religion begins with the lead essays by a scientist, a policy expert, and an ethicist. -

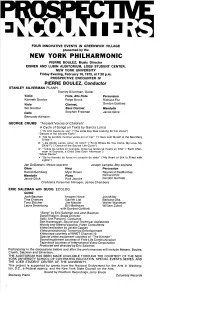

Prospective Encounters

FOUR INNOVATIVE EVENTS IN GREENWICH VILLAGE presented by the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PIERRE BOULEZ, Music Director EISNER AND LUBIN AUDITORIUM, LOEB STUDENT CENTER, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Friday Evening, February 18, 1972, at 7:30 p.m. PROSPECTIVE ENCOUNTER IV PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor STANLEY SILVERMAN PLANH Stanley Silverman, Guitar Violin Flute, Alto Flute Percussion Kenneth Gordon Paige Brook Richard Fitz Viola Clarinet, Gordon Gottlieb Sol Greitzer Bass Clarinet Mandolin Cello Stephen Freeman Jacob Glick Bernardo Altmann GEORGE CRUMB "Ancient Voices of Children" A Cycle of Songs on Texts by Garcia Lorca I "El niho busca su voz" ("The Little Boy Was Looking for his Voice") "Dances of the Ancient Earth" II "Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar" ("I Have Lost Myself in the Sea Many Times") III "6De d6nde vienes, amor, mi nino?" ("From Where Do You Come, My Love, My Child?") ("Dance of the Sacred Life-Cycle") IV "Todas ]as tardes en Granada, todas las tardes se muere un nino" ("Each After- noon in Granada, a Child Dies Each Afternoon") "Ghost Dance" V "Se ha Ilenado de luces mi coraz6n de seda" ("My Heart of Silk Is Filled with Lights") Jan DeGaetani, Mezzo-soprano Joseph Lampke, Boy soprano Oboe Harp Percussion Harold Gomberg Myor Rosen Raymond DesRoches Mandolin Piano Richard Fitz Jacob Glick PaulJacobs Gordon Gottlieb Orchestra Personnel Manager, James Chambers ERIC SALZMAN with QUOG ECOLOG QUOG Josh Bauman Imogen Howe Jon Miller Tina Chancey Garrett List Barbara Oka Tony Elitcher Jim Mandel Walter Wantman Laura Greenberg Bill Matthews -

<Pkthouse Condemned

An Associated Collegiate Press Four-Star All-American Newspaper TUESDAY September 16, 1997 Volume 124 • THE • Number 4 Non-Profit Org. U.S . Postage Paid Newark, DE 250 Student Center• University of Delaware • Newark, DE 19716 Pennit No. 26 Police issue 112 charges in weekend crackdown BY KENDRA SINEATH As part of the Multi-Agency "But the next minute everybody was were carding people left and right - violators. Most of the City News Editor Alcohol Enforcement Project, the running, trying to get away from the luckily for us, everyone they carded ·:It's been a while since we've had In a ci tywide crackdown on Newark Police Special Operations cops.'· was over 21 .'' this type of heightened enforcement," underage drinking and excessive noise, Unit, in conjunction with the Delaware The streets hardest hit were, Haines Pink's housemates have a Sept. 25 he said. '·and students were just not arrests were 112 charges were made last weekend A lcoholi c Beverage Control Street, Madison A venue, Wilbur Street court date. where they plan to contest prepared to deal with the aggression of w:th offenses ranging from underage Enforcement Section, used six plain and New London Road. the charges. this force.'' consumption of alcohol to possession clothed officers to target bars. liquor Although junior Stefanic Pink was "It was our first offense and we Even though the multi-agency for breaking of LSD. stores, pru1ies and public areas where not at her Haines Street home at the didn't even get a warning." she said. "I enforcement project put into effect last "The majority of the arrests made underage drinking has been a problem. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Williams, Justin A. (2010) Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop Music: Theoretical Frameworks and Case Studies

Williams, Justin A. (2010) Musical borrowing in hip-hop music: theoretical frameworks and case studies. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. Access from the University of Nottingham repository: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11081/1/JustinWilliams_PhDfinal.pdf Copyright and reuse: The Nottingham ePrints service makes this work by researchers of the University of Nottingham available open access under the following conditions. · Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. · To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in Nottingham ePrints has been checked for eligibility before being made available. · Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not- for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. · Quotations or similar reproductions must be sufficiently acknowledged. Please see our full end user licence at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/end_user_agreement.pdf A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the repository url above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact [email protected] MUSICAL BORROWING IN HIP-HOP MUSIC: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS AND CASE STUDIES Justin A. -

THE TIME of OUR LIVES: LEARNING from the TIME EXPERIENCES of TEACHERS and ADMINISTRATORS DWGA PEMOD of EDUCATIONAL Refohii

THE TIME OF OUR LIVES: LEARNING FROM THE TIME EXPERIENCES OF TEACHERS AND ADMINISTRATORS DWGA PEMOD OF EDUCATIONAL REFOhiI A thesis submitted in confonnity with the requirements for the degree oCDoctor of Philosophy, Graduate Deparunent of Theory and Policy Studies in Education. Ontario Institute for Studies in EducatiodUniversity of Toronto O Copyright by Ciayton Laîleur 200 1 BitiIbthéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Eibliigraphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wetlington Street 395. nie Wellinglon Ottewa ON K1A ON4 Oltawa ON K1A ON4 CaMda CaMda Yowb VafmriMnrr* Our kb Nam rd* The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Lïbrary of Canada to Bibliotkque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seU reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/Eilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format éiectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son ~ermission. autorisation. The Time of Our Lives A thesis szibmitted in conformity with the reqiiirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, -

MOBO Performers PR

**Embargoed until 00.01 Wednesday September 24, 2008** MOBO AWARDS LINE UP SUPERSTARS ESTELLE AND JOHN LEGEND CONFIRM MOBO PERFORMANCES SUGABABES TEAM UP WITH TAIO CRUZ FOR UNIQUE COLLABORATION Stars from the US and UK will line-up up to play the prestigious MOBO Awards at Wembley Arena on Wednesday October 15 th . British superstar Estelle is determined to steal the show and looks set to shine on the night after receiving 5 nominations for this year’s Awards. The Londoner has achieved huge acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic with her album Shine this year. She will take her place in a line up that also includes her American mentor, label manager and fellow megastar John Legend , who was introduced to Estelle by mutual friend Kanye West. Legend signed the British singer to his Hometown Records label and launched her into the musical stratosphere. For Legend, it is doubly satisfying for Estelle to be the hot favourite on the night, “I am so excited to be able to perform at MOBO and showcase some songs from my new album,” says Legend, “I am so happy that Estelle is nominated 5 times too! She is a huge talent and it has been great to be part of her story.” Legend’s own eagerly awaited new album, Evolver , is released in October and features Estelle, Kanye West and Andre 3000. Bridging the Atlantic is Londoner Taio Cruz , a player in the US music scene where he has written for Usher, Mya and Britney Spears and had his own career mentored by Dallas Austin.