Institutional Mythology and Historical Reality George M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Special Investigative Counsel Regarding the Actions of the Pennsylvania State University Related to the Child Sexual Abuse Committed by Gerald A

Report of the Special Investigative Counsel Regarding the Actions of The Pennsylvania State University Related to the Child Sexual Abuse Committed by Gerald A. Sandusky Freeh Sporkin & Sullivan, LLP July 12, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Scope of Review and Methodology ..........................................................................................8 Independence of the Investigation .........................................................................................11 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................13 Findings Recommendations for University Governance, Administration, and the Protection of Children in University Facilities and Programs Timeline of Significant Events ................................................................................................19 Chapter 1: The Pennsylvania State University – Governance and Administration ...........................................................................................................................31 I. Key Leadership Positions A. President B. Executive Vice President and Provost (“EVP‐ Provost”) C. Senior Vice President ‐ Finance and Business (“SVP‐ FB”) D. General Counsel II. Principal Administrative Areas A. University Police and Public Safety (“University Police Department”) B. Office of Human Resources (“OHR”) C. Department of Intercollegiate Athletics (“Athletic Department”) D. Outreach III. Administrative Controls A. Policies and Procedures B. Oversight and -

Montana Kaimin, 1898-Present (ASUM)

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 10-23-1964 Montana Kaimin, October 23, 1964 Associated Students of Montana State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of Montana State University, "Montana Kaimin, October 23, 1964" (1964). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 4084. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/4084 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 9 to 5 in Lodge Today Freshmen Vote for CB Delegates JACK CURRIERO GENE MEAD STEVE KNIGHT GLENDA LARSON CLIFF CHRISTIAN JACK CRAWFORD Chemistry Major Undecided Liberal Arts Business Administration History-Political Science Pre-Law Wayne, N. J. Spokane, Wash. West Terrehaute, Ind. Thompson Falls Helena Glasgow State Economy Has Never MONTANA KAIMIN Been Better, Babcock Says Montana State University Vol. 67, No. 14 The economy of the state has ocratic undersecretary of agricul Missoula, Montana a n independent d a i l y n e w s p a p e r Friday, October 23, 1964 never been better, Gov. Babcock ture last year. said here yesterday. Mr. Renne’s “philosophy is not Montana has gone from a $2% the type that fits a true Montan million deficit to a $2 million sur an,” the governor said. -

Curriculum Vitae DAVID L

July 13, 2020 curriculum vitae DAVID L. PASSMORE [email protected] +1.814.689.9337 personal web pages: http://DavidPassmore.net CURRICULUM VITAE OF DAVID L. PASSMORE CONTENTS CURRENT AFFILIATIONS .................................................................................................................................................................................1 EDUCATION ............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 PERSONAL, CONTACT, & INDEXING INFORMATION .........................................................................................................................2 AWARDS & HONORS .........................................................................................................................................................................................2 PREVIOUS PROFESSIONAL WORK EXPERIENCE .............................................................................................................................3 EDITORIAL WORK ...............................................................................................................................................................................................5 PUBLICATIONS .....................................................................................................................................................................................................6 BOOKS, MONOGRAPHS, -

2014 Penn Staters for Responsible Stewardship Endorsed Candidates

2014 Penn Staters for Responsible Stewardship Endorsed Candidates Albert L. Lord (1967) Alice Pope (1979, 1983g, 1986g) Robert C. Jubelirer (1959, 1962JD) Al’s Position Statement Alice’s Position Statement Bob’s Position Statement (Ballot Position 22) (Ballot Position 27) (Ballot Position 28) I walked onto the Ogontz (now Abington) If elected as trustee, I will: Serious challenges continue to face our Campus mid-December, 1963. Since, I have Honor our past: I will help find meaningful University. The Board needs an infusion of felt an outsized, almost inexplicable new blood to support the alumni-elected ways to acknowledge and publicize Penn affection for Penn State. Though a very trustees from 2012 and 2013. Yet, we must State's long tradition of academic and average student I always have felt fortunate still rely on the considerable advantages of athletic success, including the to possess a Penn State degree. Penn State’s life and professional experiences. Two contributions of the Paterno family. relentless evolution from just a state valuable attributes I bring are well-directed Planning for the future requires building university to America’s best has been a fifty advocacy, and insight into effectively on our past. year source of pride. engaging state officials and legislators. Renew our pride: I will insist that the Better than others, Graham Spanier and Joe Twenty-six years in top legislative board re-examine the events surrounding Paterno created the healthy alliance of leadership taught me valuable skills that the Sandusky scandal. We will develop a academics and athletics. Penn State wins apply here: Bringing people with differing clear and honest understanding of these national championships in several sports interests together for results, as well as events that can be used to prevent child and graduates America’s best prepared regrouping and forging ahead after predators from harming children, at Penn students. -

Penn State: Symbol and Myth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholar Commons | University of South Florida Research University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-10-2009 Penn State: Symbol and Myth Gary G. DeSantis University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation DeSantis, Gary G., "Penn State: Symbol and Myth" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1930 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Penn State: Symbol and Myth by Gary G. DeSantis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Humanities and American Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Robert E. Snyder, Ph.D. Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. James Cavendish, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 10, 2009 Iconography, Religion, Culture, Democracy, Education ©Copyright 2009, Gary G. DeSantis Table of Contents Table of Contents i Abstract ii Introduction 1 Notes 6 Chapter I The Totemic Image 7 Function of the Mascot 8 History of the Lion 10 The Nittany Lion Mascot 10 The Lion Shrine 12 The Nittany Lion Inn 16 The Logo 18 Notes 21 Chapter II Collective Effervescence and Rituals 23 Football During the Progressive Era 24 History of Beaver Field 27 The Paterno Era 31 Notes 36 Chapter III Food as Ritual 38 History of the Creamery 40 The Creamery as a Sacred Site 42 Diner History 45 The Sticky 46 Notes 48 Conclusion 51 Bibliography 55 i Penn State: Symbol and Myth Gary G. -

Download This

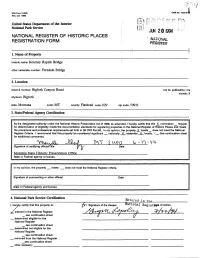

'/•""•'/• fc* NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-00 (Rev. Oct 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUN20I994 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES NATIONAL REGISTRATION FORM REGISTER 1. Name of Property historic name: Kearney Rapids Bridge other name/site number: Ferndale Bridge 2. Location street & number: Bigfork Canyon Road not for publication: n/a vicinity: X cityAown: Bigfork state: Montana code: MT county: Rathead code: 029 zip code: 59911 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _ nationally X statewide X locally. (_ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official/Title \fjF~ Date Montana State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency or bureau In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification Entered in t I, hereby certify that this property is: Signature of the Keeper National Begistifte of Action ^/entered in the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined not eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ removed from the National Register _see continuation sheet _ other (explain): ___________ Kcarnev Rapids Bridge Flathead County. -

Rocky Boy's Reservation Timeline

Rocky Boy’s Reservation Timeline Chippewa and Cree Tribes March 2017 The Montana Tribal Histories Reservation Timelines are collections of significant events as referenced by tribal representatives, in existing texts, and in the Montana tribal colleges’ history projects. While not all-encompassing, they serve as instructional tools that accompany the text of both the history projects and the Montana Tribal Histories: Educators Resource Guide. The largest and oldest histories of Montana Tribes are still very much oral histories and remain in the collective memories of individuals. Some of that history has been lost, but much remains vibrant within community stories and narratives that have yet to be documented. Time Immemorial – “This is an old, old story about the Crees (Ne-I-yah-wahk). A long time ago the Indians came from far back east (Sah-kahs-te-nok)… The Indians came from the East not from the West (Pah-ki-si-mo- tahk). This wasn’t very fast. I don’t know how many years it took for the Indians to move West.” (Joe Small, Government. Ethnic Heritage Studies Program: Plains Indians, Cheyenne-Cree-Crow-Lakota Sioux. Bozeman, MT: Center for Bilingual/Multicultural Education, College of Education, Montana State University, 1982. P. 4) 1851 – Treaty with the Red Lake and Pembina Chippewa included a land session on both sides of the Red River. 1855 – Treaty negotiated with the Mississippi, Pillager, and Lake Winnibigoshish bands of Chippewa Indians. The Tribes ceded a portion of their aboriginal lands in the Territory of Minnesota and reserved lands for each tribe. The treaty contained a provision for allotment and annuities. -

New York Times 1 November 5, 2011 Former Coach at Penn State Is Charged with Abuse by MARK VIERA

New York Times 1 November 5, 2011 Former Coach at Penn State Is Charged With Abuse By MARK VIERA A former defensive coordinator for the Penn State football team was arrested Saturday on charges of sexually abusing eight boys across a 15-year period. Jerry Sandusky, 67, who had worked with needy children through his Second Mile foundation, was arraigned and released on $100,000 bail after being charged with 40 counts related to sexual abuse of young boys. Two top university officials — Gary Schultz, the senior vice president for finance and business, and Tim Curley, the athletic director — were charged Saturday with perjury and failure to report to authorities what they knew of the allegations, as required by state law. “This is a case about a sexual predator who used his position within the university and community to repeatedly prey on young boys,” the Pennsylvania attorney general, Linda Kelly, said in a statement. Mr. Sandusky was an assistant defensive coach to Joe Paterno, the coach with the most career victories in major college football, who helped propel Penn State to the top tiers of the sport. Until now, the Big Ten university had one of the most sterling images in college athletics, largely thanks to Mr. Paterno and his success in 46 seasons as head coach. A grand jury said that when Mr. Paterno learned of one allegation of abuse in 2002, he immediately reported it to Mr. Curley. The grand jury did not implicate Mr. Paterno in any wrongdoing,though it was unclear if he ever followed up on his initial conversation with Mr. -

Have Sued the NCAA

IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS OF CENTRE COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA GEORGE SCOTT PATERNO, ) as duly appointed representative of the ) ESTATE and FAMILY of JOSEPH PATERNO; ) ) RYAN MCCOMBIE, ANTHONY LUBRANO, ) Civil Division AL CLEMENS, PETER KHOURY, and ) ADAM TALIAFERRO, members of the ) Docket No. ____________ Board of Trustees of Pennsylvania State University; ) ) PETER BORDI, TERRY ENGELDER, ) SPENCER NILES, and JOHN O’DONNELL, ) members of the faculty of Pennsylvania State University; ) ) WILLIAM KENNEY and JOSEPH V. (“JAY”) PATERNO, ) former football coaches at Pennsylvania State University; and ) ) ANTHONY ADAMS, GERALD CADOGAN, ) SHAMAR FINNEY, JUSTIN KURPEIKIS, ) RICHARD GARDNER, JOSH GAINES, PATRICK MAUTI, ) ANWAR PHILLIPS, and MICHAEL ROBINSON, ) former football players of Pennsylvania State University, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION ) (“NCAA”), ) ) MARK EMMERT, individually ) and as President of the NCAA, and ) ) EDWARD RAY, individually and as former ) Chairman of the Executive Committee of the NCAA, ) ) Defendants. ) ) COMPLAINT Plaintiffs, by and through counsel, hereby file this complaint against the National Collegiate Athletic Association (“NCAA”), its President Mark Emmert, and the former Chairman of its Executive Committee Edward Ray. INTRODUCTION 1. This action challenges the unlawful conduct of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (“NCAA”), its President, and the former Chairman of its Executive Committee in connection with their improper interference in and gross mishandling of a criminal matter that falls far outside the scope of their authority. In particular, this lawsuit seeks to remedy the harms caused by their unprecedented imposition of sanctions on Pennsylvania State University (“Penn State”) for conduct that did not violate the NCAA’s rules and was unrelated to any athletics issue the NCAA could permissibly regulate. -

Frank Bird Linderman, Author (1869-1938)

Frank Bird Linderman 1869 - 1938 “Sign-Talker with a Straight Tongue” FRANK BIRD LINDERMAN (1869 – 1938) carved a notable niche in Western literature by recording faithfully Plains Indian tales, legends, and customs. And, in the end, he succeeded as a writer because “he was Doer before he was a Teller.” LINDERMAN WAS BORN on September 25, 1869 in Cleveland, Ohio but moved to Montana’s Flathead Valley when he was only 16. After enjoying a variety of careers – including trapper, cowhand, assayer, newspaper editor and politician – Linderman, with his wife and three daughters, moved to the west shore of Flathead Lake in 1917. There he devoted his full attention to writing. Before his death in 1938, he published 5 volumes of traditional Native American lore, 2 trapper novels, 2 recorded Indian biographies, one volume of poetry, a juvenile nature tale, and numerous periodical pieces. LINDERMAN HAD BEEN a friend of Montana’s Native American people since his earliest days in the state (even playing an instrumental role in the establishment of Rocky Boy’s Reservation for the Chippewa and Cree in 1916). In his writing about these peoples, Linderman proved to be a perfectionist. He diligently interviewed tribal elders, and always checked his interpreter’s translation through his expert use of sign language. Frank Linderman may have begun as an amateur ethnographer, but his publications exhibit a writer of immense integrity, clarity, and humility – an absolutely trustworthy observer and recorder, a “creative listener.” THE “SIGN-TALKER WITH A STRAIGHT TONGUE” was adopted into the Blackfeet, the Cree, and the Crow tribes. -

Library Official Takes Issue with Funding Formula

11/20/12 ● Publisher: NewsLanc.com, LLC ● Volume II, No. 184 Library official takes issue with funding formula INTELLIGENCER JOURNAL NEW ERA: The EDITOR: The article merits a careful reading. funding formula for local libraries isn’t fair, a top city library official says. As we have previously pointed out, either there should be a System that owns and operates the The Lancaster Public Library on Duke Street and its library or there should be libraries that simply branches in Leola and Mountville cover 40 percent contract for services with a much scaled back of the county’s service area but receive only 29 System. Right now we have the worst of both worlds percent of state allocations, city library board with the ridiculousness of each library, tiny or president Todd Smith said… gigantic, only having one vote in decision making. Further, Smith said, far too much money is spent at When Lancaster Public Library (LPL) president the system level, never making it to the county’s Scott Todd told the System board that LPL is at a member libraries. For instance, Smith said, only 8 “breaking point”, this might foreshadow an LPL exit percent of the $2.1 million allocated by the county and the death knell of the bloated System. RIP. for library services goes to the libraries; the rest, he said, is spent at the system level… One Year Later, Alumni Watchdog Group Raises More Questions Penn Staters for Responsible Stewardship intense judicial scrutiny for allowing a suspected continues to pressure board of trustees pedophile to remain in contact with children? on need for objective investigation, immediate resignations and transparent leadership 4. -

Acknowledging the Past While Looking to the Future: Exploring Indigenous Child Trauma

Acknowledging the Past while Looking to the Future: Exploring indigenous child trauma Shanley Swanson Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education Norway Spring 2012 Acknowledging the Past while Looking to the Future: Exploring Indigenous Child Trauma By Shanley M. Swanson Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education University of Tromsø Norway Spring 2012 Supervised by Merete Saus, PhD, Head of department, Regionalt kunnskapssenter for barn og unge – Nord ii iii For Sage and Dean iv v Acknowledgements “No matter what you accomplished, somebody helped you.” –Althea Gibson, African American athlete It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible. First and foremost I would like to thank my interviewees. I am grateful for the stories and knowledge you’ve shared with me. I respectfully wish you each the best in your important work. To the Center for Sámi Studies, and in particular Bjørg Evjen, Hildegunn Bruland and Per Hætta, for this wonderful opportunity. Your support and encouragement throughout this process has been gratefully appreciated. I am thankful to Kate Shanley and all of my teachers in the fields of indigenous studies, social work, Native American studies, psychology and art for inspiring me and contributing to my education. Thanks to all of my former clients and their children for teaching me the really important stuff. A kjempestor thanks to my supervisor Merete Saus for her patience, guidance and kindness. Thanks to Kristin, Ketil, and the superhero also known as Bjørn for their help with little things that make a big difference.