The Last Puritan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O Klahoma City

MEDIA GUIDE O M A A H C L I K T Y O T R H U N D E 2 0 1 4 2 0 1 5 THUNDER.NBA.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ALL-TIME RECORDS General Information .....................................................................................4 Year-By-Year Record ..............................................................................116 All-Time Coaching Records .....................................................................117 THUNDER OWNERSHIP GROUP Opening Night ..........................................................................................118 Clayton I. Bennett ........................................................................................6 All-Time Opening-Night Starting Lineups ................................................119 2014-2015 OKLAHOMA CITY THUNDER SEASON SCHEDULE Board of Directors ........................................................................................7 High-Low Scoring Games/Win-Loss Streaks ..........................................120 All-Time Winning-Losing Streaks/Win-Loss Margins ...............................121 All times Central and subject to change. All home games at Chesapeake Energy Arena. PLAYERS Overtime Results .....................................................................................122 Photo Roster ..............................................................................................10 Team Records .........................................................................................124 Roster ........................................................................................................11 -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

You Never Saw a Fish on the Wall with Its Mouth Shut

IAN WINTER QC YOU NEVER SAW A FISH ON THE WALL WITH ITS MOUTH SHUT THE PRIVILEGE AGAINST SELF-INCRIMINATION AND THE DECISION OF THE COURT OF APPEAL IN R V K [2009] EWCA CRIM 1640 ISSUE NINE WINTER 2009 PUBLISHED BY CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS Nicholas Purnell QC Richard Horwell QC John Kelsey-Fry QC Timothy Langdale QC Ian Winter QC Jonathan Barnard Clare Sibson Cloth Fair Chambers specialises in fraud and commercial crime, complex and organised crime, regulatory and disciplinary matters, defamation and in broader litigation areas where specialist advocacy and advisory skills are required. 2 CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS IAN WINTER QC YOU NEVER SAW A FISH ON THE WALL WITH ITS MOUTH SHUT1 THE PRIVILEGE AGAINST SELF-INCRIMINATION AND THE DECISION OF THE COURT OF APPEAL IN R V K [2009] EWCA CRIM 1640 ISSUE NINE WINTER 2009 PUBLISHED BY CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS 1 Unreliably attributed to Sally Berger but the true origin is unclear. King John, pressured by the barons and threatened with insurrection, reluctantly signs the great charter on the Thames island of Runnymede CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS he fish on the wall has its mouth open unreliable testimony produced as a result of it. because it couldn’t resist the temptation to open it when the occasion appeared to Had paragraph 38 of Magna Carta remained the law, which justify doing so. There are few convicted could have been the case even once the use of torture had defendants who likewise could resist the been outlawed2, the question over the admissibility of the temptation to open their mouths and accused’s statement would not have been whether the Tthereby assist their prosecutors with their own words. -

Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 094 892 PS 007 449 AUTHOR Snyder, Agnes TITLE Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 421p. AVAILABLE FROM Association for Childhood Education International, 3615 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 ($9.50, paper) EDRS PRICE NF -$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Biographical Inventories; *Early Childhood Education; *Educational Change; Educational Development; *Educational History; *Educational Philosophy; *Females; Leadership; Preschool Curriculum; Women Teachers IDENTIFIERS Association for Childhood Education International; *Froebel (Friendrich) ABSTRACT The lives and contributions of nine women educators, all early founders or leaders of the International Kindergarten Union (IKU) or the National Council of Primary Education (NCPE), are profiled in this book. Their biographical sketches are presented in two sections. The Froebelian influences are discussed in Part 1 which includes the chapters on Margarethe Schurz, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Susan E. Blow, Kate Douglas Wiggins and Elizabeth Harrison. Alice Temple, Patty Smith Hill, Ella Victoria Dobbs, and Lucy Gage are- found in the second part which emphasizes "Changes and Challenges." A concise background of education history describing the movements and influences preceding and involving these leaders is presented in a single chapter before each section. A final chapter summarizes the main contribution of each of the women and also elaborates more fully on such topics as IKU cooperation with other organizations, international aspects of IKU, the writings of its leaders, the standardization of curriculuis through testing, training teachers for a progressive program, and the merger of IKU and NCPE into the Association for Childhood Education.(SDH) r\J CS` 4-CO CI. -

George Santayana: a Critical Anomaly Carol Ann Erickson University of Nebraska at Omaha

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 2-1966 George Santayana: A critical anomaly Carol Ann Erickson University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Erickson, Carol Ann, "George Santayana: A critical anomaly" (1966). Student Work. 55. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/55 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE 1SANT.A.YANA, CRITICAL ANOMALY A Thesis J 4;) Presented to the Department o.f English and the Fa~ulty or the Oollege of Graduate Studies :University of Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degre& Master of Arts by -Carol A. Erickson February 1966 UM I Number: EP72700 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material ~ad to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ' UMf. UMI EP72700 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 13'1·6 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 - 1346 Accepted for the faculty of the College of Graduate Studies of the University of Omaha, 1n_part1al fulfillment of.the requirements for the degree Master of Arts. -

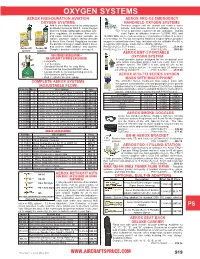

Oxygen Systems

OXYGEN SYSTEMS AEROX HIGH-DURATION AVIATION AEROX PRO-O2 EMERGENCY OXYGEN SYSTEMS HANDHELD OXYGEN SYSTEMS Add to your flying comfort by using oxygen Provides oxygen until the aircraft can reach a lower at altitudes as low as 5000 ft. Aerox Oxygen altitude. And because Pro-O2 is refillable, there is no CM Systems include lightweight aluminum cyl in- need to purchase replacement O2 cartridges. During ders, regulators, all hardware, flow meter, short flights at altitudes between 12,500ft. MSL and and nasal cannulas (masks available as 14,000ft. MSL where maneuvering over mountains or turbulent weather option). Oxysaver oxygen saving cannulas is necessary, the Pro-O2 emergency handheld oxygen system provides & Aerox Flow Control Regulators increase oxygen to extend these brief legs. Included with the refillable Pro-O2 is WP the duration of oxygen supply about 4 times, a regulator with gauge, mask and a refillable cylinder. and prevent nasal irritation and dryness. Pro-O2-2 (2 Cu. Ft./1 mask)........................P/N 13-02735 .........$328.00 Aerox 2D Aerox 4M Complete brochure available on request. Pro-O2-4 (2 Cu. Ft./2 masks) ......................P/N 13-02736 .........$360.00 system system AEROX EMT-3 PORTABLE 500 SERIES REGULATOR – AN AIRCRAFT SPRUCE EXCLUSIVE! OXYGEN SYSTEM ME A small portable system designed for the occasional user • Low profile who wants something smaller and less costly than a full • 1, 2, & 4 place portable system. The EMT-3 is also ideal for use as an • Standard Aircraft filler for easy filling emergency oxygen system. The system lasts 25 minutes at • Convenient top mounted ON/OFF valve 2.5 LPM @ 25,000 FT. -

Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs

2013-14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs 60 Atlanta Hawks 10 Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs Gold 60 Atlanta Hawks 5 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs 88 Atlanta Hawks 325 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs Gold 88 Atlanta Hawks 25 Dennis Schroder Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 23 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys 25 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys Prime 25 Atlanta Hawks 25 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs 4 Atlanta Hawks 15 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs Prime 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink 56 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink Gold 56 Atlanta Hawks 5 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs 1 Atlanta Hawks 35 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 1 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs 4 Atlanta Hawks 25 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs Gold 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs 10 Atlanta Hawks 15 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs Prime 10 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink 23 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink Gold 23 Atlanta Hawks 5 Pero Antic Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 43 Atlanta Hawks 299 Spud Webb Main Exhibit Signatures 2 Atlanta Hawks 75 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs 3 Atlanta Hawks 199 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 3 Atlanta Hawks 25 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs 31 Atlanta Hawks 325 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs Gold 31 Atlanta Hawks 25 groupbreakchecklists.com 13/14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Bill Sharman Top-Notch Autographs -

Character and Opinion in the United States

GEORGE SANTAYANA Character & Opinion in the United States NEW YORK GEORGE BRAZILLER l 955 PUBLISHED BY GEORGE BRAZILLER, INC. l o a n s ta c k MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA :B 9 4 ~ 5 SZ3C5 CONTENTS \ 9 5 * 5 CHARACTER AND OPINION IN THE UNITED STATES Preface 3 >/ I. The Moral Background 6 H. The Academic Environment 24 ill. W illiam James 39 IV. Josiah Royce 57 v. Later Speculations 79 V VI. Materialism and Idealism in American L ife 93 VII. English Liberty in America 108 381 Character and Opinion in United States PREFACE H E major part of this book is composed of lectures originally addressed to British audiences. I have added a good deal, but I make no apology, now that theT whole may fall under American eyes, for preserving the tone and attitude of a detached observer. Not at all on the ground that “ to see ourselves as others see us” would be to see ourselves truly; on the contrary, I agree with Spinoza where he says that other people’s idea of a man is apt to be a better expression of their nature than of his. I accept this prin ciple in the present instance, and am willing it should be ap plied to the judgments contained in this book, in which the reader may see chiefly expressions of my own feelings and hints of my own opinions. Only an American—and I am not one except by long association1—can speak for the heart of America. I try to understand it, as a family friend may who has a different temperament j but it is only my own mind that I speak for at bottom, or wish to speak for. -

Justus Buchler Biography

Justus Buchler Biography Table of Contents BookRags Biography....................................................................................................1 Justus Buchler.......................................................................................................1 Copyright Information..........................................................................................1 Justus Buchler Biography............................................................................................2 Works....................................................................................................................2 Further Reading....................................................................................................5 Dictionary of Literary Biography Biography.......................................................8 i BookRags Biography Justus Buchler For the online version of BookRags' Justus Buchler Biography, including complete copyright information, please visit: http://www.bookrags.com/biography/justus−buchler−dlb/ Copyright Information Kathleen A. Wallace, Hofstra University.. Dictionary of Literary Biography. ©2005−2006 Thomson Gale, a part of the Thomson Corporation. All rights reserved. (c)2000−2006 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BookRags Biography 1 Justus Buchler Biography Name: Justus Buchler Birth Date: March 27, 1914 Death March 19, 1991 Date: Nationality: American Gender: Male Works WRITINGS BY THE AUTHOR:BOOKS • Charles Peirce's Empiricism (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1939; New York: -

The Letters of George Santayana Book Two, 1910—1920

The Letters of George Santayana Book Two, 1910—1920 To Josephine Preston Peabody Marks [1910 or 1911] • Cambridge, Massachusetts (MS: Houghton) COLONIAL CLUB CAMBRIDGE Dear Mrs Marks1 Do you believe in this “Poetry Society”? Poetry = solitude, Society = prose, witness my friend Mr. Reginald Robbins!2 I may still go to the dinner, if it comes during the holidays. In that case, I shall hope to see you there. Yours sincerely GSantayana 1Josephine Preston Peabody (1874–1922) was a poet and dramatist whose plays kept alive the tradition of poetic drama in America. Her play, The Piper, was produced in 1909. She was married to Lionel Simeon Marks, a Harvard mechanical engineering professor. 2Reginald Chauncey Robbins (1871–1955) was a writer who took his A.B. from Harvard in 1892 and then did graduate work there. To William Bayard Cutting Sr. [January 1910] • [Cambridge, Massachusetts] (MS: Unknown) His intellectual life was, without question, the most intense, many-sided and sane that I have ever known in any young man,1 and his talk, when he was in college, brought out whatever corresponding vivacity there was in me in those days, before the routine of teaching had had time to dull it as much as it has now … I always felt I got more from him than I had to give, not only in enthu- siasm—which goes without saying—but also in a sort of multitudinousness and quickness of ideas. [Unsigned] 1William Bayard Cutting Jr. (1878–1910) was a member of the Harvard class of 1900. He served as secretary of the vice consul in the American consulate in Milan (1908–9) and Secretary of the American Legation, Tangier, Morocco (1909). -

Player - Spectra (17-18) Basketball

Set Info - Player - Spectra (17-18) Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Donovan Mitchell 1424 273 324 339 488 Malik Monk 1424 273 324 339 488 Jonathan Isaac 1424 273 324 339 488 Lauri Markkanen 1424 273 324 339 488 Kyle Kuzma 1424 273 324 339 488 Bam Adebayo 1424 273 324 339 488 Dennis Smith Jr. 1424 273 324 339 488 Frank Ntilikina 1424 273 324 339 488 Jordan Bell 1424 273 324 339 488 John Collins 1423 273 324 339 487 Markelle Fultz 1275 273 175 339 488 Jayson Tatum 1275 273 175 339 488 Josh Jackson 1275 273 175 339 488 Lonzo Ball 1275 273 175 339 488 De`Aaron Fox 1252 273 175 339 465 Zach Collins 1151 0 324 339 488 Justin Patton 1151 0 324 339 488 D.J. Wilson 1151 0 324 339 488 Harry Giles 1151 0 324 339 488 Ante Zizic 1151 0 324 339 488 Luke Kennard 1151 0 324 339 488 Derrick White 1151 0 324 339 488 TJ Leaf 1151 0 324 339 488 Semi Ojeleye 1151 0 324 339 488 Kristaps Porzingis 1091 273 90 339 389 Frank Mason III 1085 273 324 0 488 Rudy Gobert 1075 273 0 339 463 Nikola Jokic 1040 273 189 339 239 Giannis 1031 273 90 378 290 Antetokounmpo Kyrie Irving 981 273 90 528 90 Blake Griffn 981 273 90 528 90 Karl-Anthony Towns 941 273 90 378 200 Kevin Durant 941 273 0 528 140 Andrew Wiggins 891 273 90 528 0 Kemba Walker 851 273 189 189 200 Anthony Davis 831 273 90 378 90 Damian Lillard 831 273 90 378 90 Dwayne Bacon 827 0 0 339 488 Terrance Ferguson 827 0 0 339 488 Jarrett Allen 827 0 0 339 488 Caleb Swanigan 827 0 0 339 488 Frank Jackson 812 0 324 0 488 Ivan Rabb 812 0 324 -

NCAA Men's Final Four Records (The Final Four)

The Final Four Championship Results ............................... 8 Final Four Game Records.......................... 9 Championship Game Records ............... 12 Semifinal Game Records ........................... 14 Final Four Two-Game Records ............... 17 Final Four Cumulative Records .............. 18 8 CHAMPIONSHIP RESULts Championship Results Year Champion Score Runner-Up Third Place Fourth Place 1939 Oregon 46-33 Ohio St. † Oklahoma † Villanova 1940 Indiana 60-42 Kansas † Duquesne † Southern California 1941 Wisconsin 39-34 Washington St. † Pittsburgh † Arkansas 1942 Stanford 53-38 Dartmouth † Colorado † Kentucky 1943 Wyoming 46-34 Georgetown † Texas † DePaul 1944 Utah 42-40 + Dartmouth † Iowa St. † Ohio St. 1945 Oklahoma St. 49-45 New York U. † Arkansas † Ohio St. 1946 Oklahoma St. 43-40 North Carolina Ohio St. California 1947 Holy Cross 58-47 Oklahoma Texas CCNY 1948 Kentucky 58-42 Baylor Holy Cross Kansas St. 1949 Kentucky 46-36 Oklahoma St. Illinois Oregon St. 1950 CCNY 71-68 Bradley North Carolina St. Baylor 1951 Kentucky 68-58 Kansas St. Illinois Oklahoma St. 1952 Kansas 80-63 St. John’s (NY) Illinois Santa Clara 1953 Indiana 69-68 Kansas Washington LSU 1954 La Salle 92-76 Bradley Penn St. Southern California 1955 San Francisco 77-63 La Salle Colorado Iowa 1956 San Francisco 83-71 Iowa Temple SMU 1957 North Carolina 54-53 ‡ Kansas San Francisco Michigan St. hotos 1958 Kentucky 84-72 Seattle Temple Kansas St. P AA 1959 California 71-70 West Virginia Cincinnati Louisville C N 1960 Ohio St. 75-55 California Cincinnati New York U. 1961 Cincinnati 70-65 + Ohio St. * St. Joseph’s Utah cKee/ 1962 Cincinnati 71-59 Ohio St. Wake Forest UCLA M 1963 Loyola (IL) 60-58 + Cincinnati Duke Oregon St.