The Iconic Malcolm: the 1990S Polarization of the Mediated Images of Malcolm X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Contemporary Rhetoric About Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X in the Post-Reagan Era

ABSTRACT THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA by Cedric Dewayne Burrows This thesis explores the rhetoric about Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X in the late 1980s and early 1990s, specifically looking at how King is transformed into a messiah figure while Malcolm X is transformed into a figure suitable for the hip-hop generation. Among the works included in this analysis are the young adult biographies Martin Luther King: Civil Rights Leader and Malcolm X: Militant Black Leader, Episode 4 of Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads, and Spike Lee’s 1992 film Malcolm X. THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Cedric Dewayne Burrows Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2005 Advisor_____________________ Morris Young Reader_____________________ Cynthia Leweicki-Wison Reader_____________________ Cheryl L. Johnson © Cedric D. Burrows 2005 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One A Dead Man’s Dream: Martin Luther King’s Representation as a 10 Messiah and Prophet Figure in the Black American’s of Achievement Series and Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads Chapter Two Do the Right Thing by Any Means Necessary: The Revival of Malcolm X 24 in the Reagan-Bush Era Conclusion 39 iii THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA Introduction “What was Martin Luther King known for?” asked Mrs. -

Thefall of Wilson Phillips

THE FALL OF WILSON PHILLIPS ·SUPERMAN R.I.P. ·'HOMEALONE' AGAIN How Spike Lee willed 'Malcolm X' THE to the screen ~ o N o o 724464 3 " , , , 111111 , -11: ENeE: Extras cast as Muslim women at.a rally in the film " B V ANN E THO M P SON p H o T o G R A p H s B y o A v o L E E SPIKE LEE'S FACE is everywhere. Two stories tall, it this is the most amount of money DESERT FORM: stares down Los Angeles' Melrose Avenue from the side of ever spent on a movie in black history, In Egypt, Denzel Spike's Joint West, the newest branch ofthe clothing em- and we had to fight to get the amount Washington,.front _porium he started three years ago. There's his face again, on we got." left, and a cast a smaller scale, on Lee's white T-shirt. And then, above that, Does it bother him that many peo- of extras set up is the real thing: beard, glasses, and intense gaze. It's a Sat- ple wearing X hats and T-shirts don't a shot of a hajj urday morning in October, and the grand opening of this know who Malcolm X really was? during the filming newest Spike's Joint. With a half-dozen camera crews fo- "Maybe wearing the hat is the first of Malcolm X cusing on him, Lee takes a giant pair of scissors and gamely step," Lee suggests, "to going to the saws at the red and green ribbons strung across the entrance. -

Black Popular Culture

BLACK POPULAR CULTURE THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL AFRICOLOGY: A:JPAS THE JOURNAL OF PAN AFRICAN STUDIES Volume 8 | Number 2 | September 2020 Special Issue Editor: Dr. Angela Spence Nelson Cover Art: “Wakanda Forever” Dr. Michelle Ferrier POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 2 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State Bowling Green State University University University JUDITH FATHALLAH KATIE FREDRICKS KIT MEDJESKY Solent University Rutgers University University of Findlay JESSE KAVADLO ANGELA M. -

James Baldwin on My Shoulder

DISPATCH The Disorder of Life: James Baldwin on My Shoulder Karen Thorsen Abstract Filmmaker Karen Thorsen gave usJames Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket, the award-winning documentary that is now considered a classic. First broadcast on PBS/American Masters in August, 1989—just days after what would have been Baldwin’s 65th birthday—the film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 1990. It was not the film Thorsen intended to make. Beginning in 1986, she and Baldwin had been collaborating on a very different film project: a “nonfiction fea- ture” about the history, research, and writing of Baldwin’s next book, Remember This House. It was also going to be a film about progress: how far we had come, how far we still had to go, before we learned to trust our common humanity. The following memoir explores how and why their collaboration began. This recollec- tion will be serialized in two parts, with the second installment appearing in James Baldwin Review’s seventh issue, due out in the fall of 2021. Keywords: The Price of the Ticket, Albert Maysles, James Baldwin, film, screen- writing After two months of phone calls and occasional faxes, I sat down facing the entrance to wait for James Baldwin. It was April 1986, and this was The Ginger Man: the fabled watering hole across from Lincoln Center named after J. P. Don- leavy’s 1955 novel of the same name—a “dirty” book by an expatriate author that was banned in Ireland, published in Paris, censored in the U.S., and is now consid- ered a classic. -

The Only Living Boy in New York

Presents THE ONLY LIVING BOY IN NEW YORK A film by Marc Webb (88 min., USA, 2017) Language: English Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Twitter: @starpr2 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia THE ONLY LIVING BOY IN NEW YORK Adrift in New York City, a recent college graduate seeks the guidance of an eccentric neighbor as his life is upended by his father’s mistress in the sharp and witty coming-of-age story The Only Living Boy in New York. Thomas Webb (Callum Turner), the son of a publisher and his artistic wife, has just graduated from college and is trying to find his place in the world. Moving from his parents’ Upper West Side apartment to the Lower East Side, he befriends his neighbor W.F. (Jeff Bridges), a shambling alcoholic writer who dispenses worldly wisdom alongside healthy shots of whiskey. Thomas’ world begins to shift when he discovers that his long-married father (Pierce Brosnan) is having an affair with a seductive younger woman (Kate Beckinsale). Determined to break up the relationship, Thomas ends up sleeping with his father’s mistress, launching a chain of events that will change everything he thinks he knows about himself and his family. The Only Living Boy in New York stars Jeff Bridges (Hell or High Water, Crazy Heart), Kate Beckinsale (Love & Friendship, Underworld), Pierce Brosnan (GoldenEye, Tomorrow Never Dies), Cynthia Nixon (“Sex and the City,” A Quiet Passion), Callum Turner (Assassin’s Creed, Tramps) and Kiersey Clemons (Justice League, Neighbors 2: Sorority Rising). -

Laughing at American Democracy: Citizenship and the Rhetoric of Stand-Up Satire

LAUGHING AT AMERICAN DEMOCRACY: CITIZENSHIP AND THE RHETORIC OF STAND-UP SATIRE Matthew R. Meier A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2014 Committee: Ellen Gorsevski, Advisor Khani Begum Graduate Faculty Representative Alberto González Michael L. Butterworth, Co-Advisor © 2014 Matthew R. Meier All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Michael L. Butterworth and Ellen Gorsevski, Co-Advisors With the increasing popularity of satirical television programs such as The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report, it is evident that satirical rhetoric has unique and significant influence on contemporary American culture. The appeal of satirical rhetoric, however, is not new to the American experience, but its preferred rhetorical form has changed over time. In this dissertation, I turn to the development of stand-up comedy in America as an example of an historical iteration of popular satire in order to better understand how the rhetoric of satire manifests in American culture and how such a rhetoric can affect the democratic nature of that culture. The contemporary form of stand-up comedy is, historically speaking, a relatively new phenomenon. Emerging from the post-war context of the late 1950s, the form established itself as an enduring force in American culture in part because it married the public’s desire for entertaining oratory and political satire. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a generation of stand- up comedians including Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce, and Dick Gregory laid the foundation for contemporary stand-up comedy by satirizing politics, racism, and social taboos. -

Official Ballot

OFFICIAL BALLOT AFI is a trademark of the American Film Institute. Copyright 2005 American Film Institute. All Rights Reserved. AFI’s 100 Years…100 CHEERS America's Most Inspiring Movies AFI has compiled this ballot of 300 inspiring movies to aid your selection process. Due to the extraordinarily subjective nature of this process, you will no doubt find that AFI's scholars and historians have been unable to include some of your favorite movies in this ballot, so AFI encourages you to utilize the spaces it has included for write-in votes. AFI asks jurors to consider the following in their selection process: CRITERIA FEATURE-LENGTH FICTION FILM Narrative format, typically over 60 minutes in length. AMERICAN FILM English language film with significant creative and/or production elements from the United States. Additionally, only feature-length American films released before January 1, 2005 will be considered. CHEERS Movies that inspire with characters of vision and conviction who face adversity and often make a personal sacrifice for the greater good. Whether these movies end happily or not, they are ultimately triumphant – both filling audiences with hope and empowering them with the spirit of human potential. LEGACY Films whose "cheers" continue to echo across a century of American cinema. 1 ABE LINCOLN IN ILLINOIS RKO, 1940 PRINCIPAL CAST Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon DIRECTOR John Cromwell PRODUCER Max Gordon SCREENWRITER Robert E. Sherwood Young Abe Lincoln, on a mission for his father, meets Ann Rutledge and finds himself in New Salem, Illinois, where he becomes a member of the legislature. Ann’s death nearly destroys the young man, but he meets the ambitious Mary Todd, who makes him take a stand on slavery. -

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

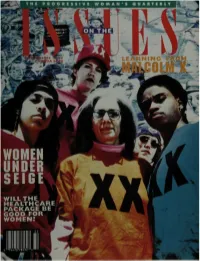

LEARNING SEIG WILL THE HEALTHCARE PACKAGE BE GOOD FOR WOMEN? Her hands are now at rest. Once they were bound. Both by her and by the strong arm of her government. Falima Ibrahim. A A speaker. A union lender for Sudanese women's rights. Her husband won an international Peace Medal. At the same moment he was executed, she was imprisoned. Denied food and medicine, Fatima fell into a coma. Yet few details of her ordeal are forgotten. Today, because of Amnesty International, and people like you, Fatima is considered lucky. She is alive'. Today, she is president of the Women's International Democratic Federation. Let no one tc our hands are bound. Pick up a pen and raise your voice for those who can't. Join Amnesty and become a Freedom Writer. Call 1-800-55-AMNESTY, It's your human right. M N Y N R N T I O N Summer 1993 Contents FEATURES 12 They Could Not be Moved: The Anti-Nazi Heroism of the White Rose by Fred Pelka 18 Healthcare for All — Will It Be Good For Women? by Elayne Clift 23 Communiques From the Front: LEARNING FROM Young Activists Chart Feminism's Third Wave MALCOLM X by Bonnie Pfister 27 29 Update: Inches From Freedom — Forever? The Prolonged Oppression of the Sahrawis by John W. Bartktt 29 What Women Can Learn From Malcolm X by Flo Kennedy and Irene Davall 44 The Deadly Denial An Interview With Feminist Author Susan Griffin by Heather Rhoads SPECIAL SECTION WOMEN UNDER SIEGE 32 For Irish Feminists: Activism=Imprisonment, Strip Search and Death by Betsy Swart The Message in the Murder of Sheena Campbell 34 Like The Phoenix We -

Film, History and Cultural Memory: Cinematic Representations of Vietnam-Era America During the Culture Wars, 1987-1995

FILM, HISTORY AND CULTURAL MEMORY: CINEMATIC REPRESENTATIONS OF VIETNAM-ERA AMERICA DURING THE CULTURE WARS, 1987-1995 James Amos Burton, BA, MA. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2007 Abstract My thesis is intended as an intellectual opportunity to take what, I argue, are the “dead ends” of work on the history film in a new direction. I examine cinematic representations of the Vietnam War-era America (1964-1974) produced during the “hot” culture wars (1987-1995). I argue that disagreements among historians and commentators concerning the (mis)representation of history on screen are stymied by either an over- emphasis on factual infidelity, or by dismissal of such concerns as irrelevant. In contradistinction to such approaches, I analyse this group of films in the context of a fluid and negotiated cultural memory. I argue that the consumption of popular films becomes part of a vast intertextual mosaic of remembering and forgetting that is constantly redefining, and reimagining, the past. Representations of history in popular film affect the industrial construction of cultural memory, but Hollywood’s intertextual relay of promotion and accompanying wider media discourses also contributes to a climate in which film impacts upon collective memory. I analyse the films firmly within the discursive moment of their production (the culture wars), the circulating promotional discourses that accompany them, and the always already circulating notions of their subjects. The introduction outlines my methodological approach and provides an overview of the relationship between the twinned discursive moments. Subsequent chapters focus on representations of returning veterans; representations of the counterculture and the anti-war protest movement; and the subjects foregrounded in the biopics of the period. -

Terence Blanchard

TERENCE BLANCHARD AWARDS & NOMINATIONS VENICE FILM FESTIVAL Passion for Film Award TIFF TRIBUTE AWARD TIFF Variety Artisan Award NAACP IMAGE AWARD NOMINATION Harriet (2020) Outstanding Soundtrack/Compilation Album HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA Harriet AWARD NOMINATION (2019) Original Score – Feature Film BMI FILM & TV AWARD (2019) Icon Award ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION BLACKkKLANSMAN (2019) Best Original Score BMI FILM & TV AWARD (2010) Icon Award GRAMMY AWARD (2019) Best Instrumental Composition Blut Und Boden (Blood And Soil) BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (2019) BLACKkKLANSMAN Best Original Music HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA BLACKkKLANSMAN AWARD NOMINATION (2018) Best Original Score: Feature Film BMI FILM & TV AWARD (2010) Classic Contribution Award GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2007) Best Long Form Music Video GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD 25th HOUR NOMINATION (2003) Best Original Score: Motion Picture WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD 25th HOUR NOMINATION (2002) Soundtrack Composer of the Year The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 TERENCE BLANCHARD FEATURE FILM BUD, NOT BUDDY Sylvain Chomet, dir. GKIDS BRUISED Guymon Casady, Terry Dougas, Brad Romulus Entertainment Feinstein, Linda Gottlieb, Gillian Hormel, Basil Iwanyk, Paris Kassidokostas-Latsis, Erica Lee prods. Halle Berry, dir. ONE NIGHT IN MIAMI Jess Wu Calder, Keith Calder, Chris Harding, ABKCO Films Jody Klein, prods. Regina King, dir. DA 5 BLOODS Spike Lee, dir. Netflix Jon Kilik, Spike Lee, Beatriz Levin, Lloyd Levin, prods. ON THE RECORD Kirby Dick, Amy Herdy, Jamie Rogers, Amy Chain Camera Pictures Ziering, prods Kirby Dick, Amy Ziering, dir. HARRIET Debra Martin Chase, Gregory Allen Howard, Focus Features Daniela Taplin Lundberg, prods. Kasi Lemmons, dir. GUILTY UNTIL PROVEN GUILTY Kate Steiker-Ginzberg, associate prod. -

Playthell Benjamin

p ,, ," SPIKE LEE: choice. For not only did Baldwin know Malcolm personally, he was also deeply committed to the black EARING liberation struggle. However, after a year of livin' large in Tinseltown at studio expense, he failed to come up with a usable and finished script. Two ~E other novelists tried their hand at it and failed: David Bradley, a black college professor and author of the celebrated novel The Chaneysville Incident, and Calder Willingham i 11 author of the novel Eternal Fire. Two Pulitzer prize-winning dramatists also bit the dust trying to produce a viable script: Charles Fuller ART AND POUTlCS, AMIR1 BARAKA AND and David Mamet. Fuller, a product of the sixties Black Arts Movement, SPIKE LEE HAVE CROSSED SWORDS "W eknow was significantly influenced-like we can't satisfy most of us of that generation-by the OVER LEE'S FILMING OF THE everybody's vision of example of Malcolm X. So there can Malcolm X. He has be no doubt that he took his task to UFE OF MALCOLM X. achieved mythic propor- heart. A brilliant playwright who has tions ...but we knew going into it taken us on marvelous excursions into that we'd have that problem," said the soul of African American culture, Spike Lee about his current work-in-progress, then he he seemed destined for the project. declared his intention "to be as honest as possible" and But alas, zilch. After Fuller wrote the "to make a great film." But in tackling this project Spike script, director Norman Jewison, with has not only undertaken a monumental artistic task, he whom Fuller had collaborated on the has also waded into troubled political waters. -

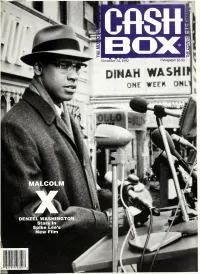

CASH CAMILLE COMPASIO Director, Coin Machine Operations LEEJESKE New York Editor RANDY CLARK Los Angeles Editor

November 14, 1992 Newspaper $3.50 DINAH WASHII ONE WEEK ONL 82791 19359 VOL LVI, NO. 12, NOVEMBER 14, 1992 STAFF BOX GEORGE ALBERT President end Publisher FRED L GOODMAN Editor In Chief/Genera! Manager CASH CAMILLE COMPASIO Director, Coin Machine Operations LEEJESKE New York Editor RANDY CLARK Los Angeles Editor MARKETING MARK WAGNER Director, Nashville MILT PETTY (LA) EDITORIAL COVER STORY MICHAEL MARTINEZ, Assoc. Ed. (LA) JOHN GOFF, Assoc. Ed. (LA) X Marks The Spot CORY CHESHIRE, Nashville Editor STEVE GIUFFRIDA (Nashville) BRAD HOGUE (Nashville) MALCOLM X was a music devotee throughout his life and numbered among GREGORY & COOPER—Gospel his friendships top musicians and entertainers of his era, so it is appropriate that (Nashville) Malcolm X, director Spike Lee's film about the life of the visionary leader is CHARTRESEARCH accompanied by two soundtrack albums and features a scene shot in front of the RAYMOND BALLARD, Chart legendary Apollo Theater which was a favorite of his. Cooidinator (LA) JOHN GILLEN (LA) Malcolm X, starring Denzel Washington in the title role, Al Freeman Jr. as the JOHN COSSIBOOM (Nash) CHRIS BERKEY (Nash) Honorable Elijah Muhammed and Angela Bassett as Betty Shabazz, opens nationwide Wednesday, November 18, a production of Lee's 40 Acres And A PRODUCTION Mule Film Works, and Producer Marvin Worth Productions. Sam Durham Former Malcolm friend and associate Quincy Jones' Qwest Records is releasing CIRCULATION on November 17 Music From The Motion Picture Malcolm X, featuring vintage NINATREGUB, Manager material used in the film and of the era. Arrested Developemnt contributes a new PUBLICATION OFFICES song, the biting "Revolution." NEW YORK A second release, trumpeter, bandleader, composer, arranger Terence 462 W.58th Street (Suite 2D) New York, NY 10019 Blanchard's Mlalcolm X The Original Motion Picture Score for Columbia is available Phone: (212) 533-0773 November 10.