Municipal Revenue Generation and Development in the Calgary and Edmonton Metropolitan Regions†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calgary Metropolitan Plan Environment Report: Strategies and Actions: Part 1

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Richard Parker Professorship Repository Calgary Regional Partnership Documents 2009 Calgary Metropolitan Plan Environment Report: Strategies and Actions: Part 1 O2 Planning + Design Inc. O2 Planning + Design Inc. Calgary Regional Partnership. (2009). Calgary Metropolitan Plan Environment Report: Strategies and Actions: Part 1. Calgary: O2 Planning + Design Inc. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/107163 report Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca CALGARY METROPOLITAN PLAN ENVIRONMENT REPORT: STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS Presented to: CALGARY REGIONAL PARTNERSHIP Presented by: O2 PLANNING + DESIGN INC. 2009 October 2010 Version Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction........................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Existing Environment ............................................................................................................ 8 2.1 Land ................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1.1 Natural Regions and Subregions............................................................................. 8 2.1.2 Landforms .............................................................................................................. 12 2.1.3 Landscape Units .................................................................................................... 14 2.1.4 Vegetation and Land Cover .................................................................................. -

WAM Industrial Park Local Area Structure Plan with Amendments

(Consolidation including Bylaw 04-16 March 22, 2016) WAM Development Group WAM Industrial Park Local Area Structure Plan Prepared by: UMA Engineering Ltd. 17007 - 107 Avenue Edmonton, AB T 780-486-7000 F 780-486-7070 www.uma.aecom.com E527-003-00-01-4.6.1 January 2008 WAM Industrial Park - Local Area Structure Plan Office Consolidation – March 22, 2016 Bylaws Amending WAM Industrial Park - LASP Bylaw No. Date 04-16 March 22, 2016 Maps 5 – 10 Replaced with Dec. 17, 2015 Version of Maps 5 - 10 NOTE: Anyone using this consolidation is advised that the amendment has been included for convenience only and that the original WAM Industrial Park LASP and the original amending Bylaws should be consulted for all purposes of interpreting and applying the Bylaws. BY-LAW NO. 40-07 OF LEDUC COUNTY IN THE PROVINCE OF ALBERTA A BYLAW OF LEDUC COUNTY TO ADOPT THE WAM INDUSTRIAL PARK LOCAL AREA STRUCTURE PLAN. WHEREAS The Council of Leduc County deems it to be in the public interest to adopt the WAM Industrial Park Local Area Structure Plan; NOW THEREFORE, THE COUNCIL OF LEDUC COUNTY, DULY ASSEMBLED, ENACTS AS FOLLOWS: That the WAM Industrial Park Local Area Structure Plan, being Schedule "An attached and forming part of this Bylaw, be adopted. This Bylaw shall take effect on the date of the third reading. Read a first time this 28th day of August, A.D., 2007. SEAL COUNTY MANAGER Read a second time this 29th day of January, A.D., 2008. Read a third time this 29th day of January, A.D., 2008. -

Annual Information Form May 18, 2000 2

WELL SERVICE LTD. Revised Annual Information Form May 18, 2000 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page THE COMPANY ................................................................... 2 BUSINESS OF THE COMPANY .......................................................... 2 Overview ................................................................. 2 History ................................................................... 3 Acquisition of Superior Oilwell Cementers Inc. ..................................... 4 Acquisition of Northline Energy Services Inc. ...................................... 4 Well Servicing Operations ..................................................... 4 Future Plans ............................................................... 5 SELECTED FINANCIAL INFORMATION ................................................... 6 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS ............................................. 7 ENVIRONMENTAL MATTERS .......................................................... 7 DIRECTORS AND OFFICERS ........................................................... 7 DIVIDEND RECORD AND POLICY ...................................................... 10 MARKET FOR COMMON SHARES OF THE COMPANY ....................................... 10 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ......................................................... 10 THE COMPANY Trican Well Service Ltd. (“Trican” or the “Company”) was incorporated under the Companies Act (Alberta) on April 11, 1979 under the name 216858 Oilwell Service Co. Ltd. The Company’s name was changed to Trican Oilwell -

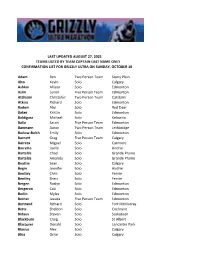

Last Updated August 27, 2021 Teams Listed by Team Captain Last Name Only Confirmation List for Grizzly Ultra on Sunday, October 10

LAST UPDATED AUGUST 27, 2021 TEAMS LISTED BY TEAM CAPTAIN LAST NAME ONLY CONFIRMATION LIST FOR GRIZZLY ULTRA ON SUNDAY, OCTOBER 10 Adam Ben Two Person Team Stony Plain Alto Kevin Solo Calgary Ashkin Allison Solo Edmonton Aslin Lynell Five Person Team Edmonton Atchison Christofer Two Person Team Carstairs Atkins Richard Solo Edmonton Badoni Atul Solo Red Deer Baker Kristin Solo Edmonton Baldigara Michael Solo Kelowna Balla Sarah Five Person Team Edmonton Banmann Aaron Two Person Team Lethbridge Barlow-Bolch Emily Solo Edmonton Barnett Greg Five Person Team Calgary Barrera Miguel Solo Canmore Barrette Joelle Solo Airdrie Bartelds Chad Solo Grande Prairie Bartelds Amanda Solo Grande Prairie Beattie Sean Solo Calgary Begin Jennifer Solo Airdrie Bentley Chris Solo Fernie Bentley Sheri Solo Fernie Bergen Roslyn Solo Edmonton Bergeron Cait Solo Edmonton Berlin Myles Solo Edmonton Bernat Jessica Five Person Team Edmonton Bertrand Richard Solo Fort McMurray Betts Sheldon Solo Cochrane Bidaux Steven Solo Saskatoon Blackburn Craig Solo St Albert Blacquier Donald Solo Lancaster Park Blasius Alex Solo Calgary Bliss Orrie Solo Calgary Boisvenue Melissa Solo Redwood Meadows Borba Renata Two Person Team Edmonton Boyd Suzanne Solo Calgary Brandt Frank Solo Steinbach Brandt Juanita Solo Calgary Bratland Lisa Solo Hythe Bratland Kailey Solo Hythe Brekkas Elana Solo Aurora Brenner Tina Two Person Team Edmonton Brescia Laura Solo Calgary Brezden Julian Solo Edmonton Brinen Peter Solo Red Deer Brochu Rachelle Two Person Team Peace River Brockman Nancy Two -

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1 Alberta Municipal Affairs, Government of Alberta November 2018 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ISBN 978-1-4601-4254-7 ISSN 2368-7320 Data for this publication are from the 2016 federal census of Canada, or from the 2018 municipal census conducted by municipalities. For more detailed data on the census conducted by Alberta municipalities, please contact the municipalities directly. © Government of Alberta 2018 The publication is released under the Open Government Licence. This publication and previous editions of the Municipal Affairs Population List are available in pdf and excel version at http://www.municipalaffairs.alberta.ca/municipal-population-list and https://open.alberta.ca/publications/2368-7320. Strategic Policy and Planning Branch Alberta Municipal Affairs 17th Floor, Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: (780) 427-2225 Fax: (780) 420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 780-420-1016 Toll-free in Alberta, first dial 310-0000. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2018 Municipal Census Participation List .................................................................................... 5 Municipal Population Summary ................................................................................................... 5 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ....................................................................................... -

Olivia Colic

Olivia Colic Managing Partner, Alberta A seasoned and trusted real estate lawyer, clients Region turn to Olivia for her practical and timely solutions Partner to help them overcome obstacles facing the real Calgary estate industry [email protected] Olivia is McCarthy Tétrault’s Regional Managing Partner for Alberta and t. +1 403-260-3661 is a partner in the firm’s Real Property & Planning Group in Calgary. Her practice encompasses all areas of commercial real estate including acquisition and sale transactions, domestic and cross-border financing, development and leasing. With more than 25 years’ experience acting as a trusted real estate advisor to property owners, lenders and borrowers, landlords, managers and tenants, Olivia’s solutions- Olivia Colic orientated approach ensures clients are successful in mitigating any multi-faceted contractual, operational and financial issues they may Managing Partner, Alberta Region face throughout Canada and abroad. Partner Calgary She’s good to deal with and knows her stuff. She takes reasonable positions on matters and her work is of a high quality. [email protected] t. +1 403-260-3661 — CHAMBERS CANADA, REAL ESTATE - ALBERTA, CLIENT INTERVIEW Bar Admission Having acted for several major property developers, pension funds, Alberta 1995 REIT’s as well as other private investors on the acquisition and disposition of office and industrial properties, hotels and shopping Law School centres, clients benefit from Olivia’s wide-range of experience on many University of Alberta commercial property financings ranging from single property loans to large financings involving complex ownership structures and properties Practices across multiple jurisdictions. She is also one of only a few lawyers in Real Estate Canada to have been invited to become a Fellow of the American Real Property Acquisitions & College of Mortgage Attorneys. -

Bylaw 31/2018 Amendment to Waste Management Bylaw Agenda Item: 5C

Town of Cochrane Council Report Meeting: Regular Council Meeting Date: October 9, 2018 Originated By: Fabrizio Bertolo, Manager, Waste & Recycling Title: Bylaw 31/2018 Amendment to Waste Management Bylaw Agenda Item: 5c RECOMMENDED ACTION That Council gives First Reading to Bylaw 31/2018. STRATEGIC / SUSTAINABILITY PLAN ITEM Town of Cochrane Strategic Plan 1.2 Future infrastructure, facilities and plans be developed and implemented to accommodate growth. 1.4 Promote/Advocate the Cochrane Sustainability Plan by aligning our plans and actions. 3.3 Promote and celebrate a culture of engagement, customer service, innovation, responsibility and accountability. Cochrane Sustainability Plan 4. We contribute to the solution on climate change BACKGROUND Attached for First Reading is Bylaw 31/2018 which proposes to amend Town of Cochrane Waste Management Bylaw 08/2018, to reduce residential waste pick up (black carts) from every week to every two weeks. Council adopted the Zero Waste Framework in the Fall of 2012 as the Town of Cochrane’s waste management vision. The Zero Waste Framework outlines how Cochrane can achieve Zero Waste by focusing on reducing our environmental footprint by minimizing the amount of waste that must be landfilled through waste reduction, reuse, recycling, redesign, composting and other actions. The overall vision is Zero Waste with the interim goal of 80% of waste diverted from the landfill by 2020. The Zero Waste Framework identifies 5 Pathways to achieving our goals: Organics (in all sectors), Multi-family Recycling, Industrial Commercial Institutional Recycling, Construction & Demolition Recycling and Events & Public Spaces. Diversion Rate for the Town of Cochrane moved from 31% (2016) to 61% after the implementation of the Organics program. -

The Fiscal Implications of Land Use

Cost of Community Services study for Red Deer County The Fiscal Implications of Land Use: A “Cost of Community Services” Study for Red Deer County MAIN REPORT The Fiscal Implications of Land Use: A “Cost of Community Services” Study for Red Deer County Report 2: MAIN REPORT Prepared by Guy Greenaway and Stephanie Sanders April 2006 Miistakis Institute c/o EVDS - University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Ph: 403-220-8968 Email: [email protected] Web: www.rockies.ca Acknowledgements In developing the methods for this study, we relied heavily on those who had gone before, and those with expertise in this area. We are particularly indebted to Mark Haggerty and Ray Rasker of the Sonoran Institute, Carl Mailler and Julia Freedgood of the American Farmland Trust, Bill Symonds of Alberta Municipal Affairs, Larissa Muller of the Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, and Mike Quinn and Greg Chernoff of the Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary. We are also grateful to the other municipalities who took the time to participate and contribute to the Cost of Community Services Multi-Municipality Workshop, specifically the representatives from County of Camrose, County of Stettler, Lacombe County, Leduc County, MD of Rocky View, Mountain View County, Strathcona County, Sturgeon County, Town of Bowden, and Wheatland County. One of the greatest difficulties we anticipated with conducting this project was appearing in the Red Deer County offices as outside researchers and facing a group of managers and staff who saw this study as an unclear academic exercise that was a drain on their already full calendars. -

2017 Municipal Affairs Population List

2017 Municipal Affairs Population List Population figures are based on the latest municipal or federal census counts reported to the Minister as of September 1, 2017 in compliance with the Determination of Population Regulation 63/2001 under Section 604 of the Municipal Government Act. Strategic Policy and Planning Branch Alberta Municipal Affairs 17th Floor, Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 2017 Municipal Affairs Population List Alberta Municipal Affairs © Government of Alberta 2018 ISSN 978-1-4601-3652-2 ISBN 2368-7320 Printed in Canada The publication is released under the Open Government Licence. This publication and previous editions of the Municipal Affairs Population are available in pdf and excel version at http://www.municipalaffairs.alberta.ca/mc_official_populations and http://open.alberta.ca/publications/2368-7320. Data for this publication are from the 2016 federal census of Canada, or from the 2016 or 2017 municipal census conducted by municipalities. For more detailed data on the census conducted by Alberta municipalities, please contact the municipalities directly. Questions concerning the Municipal Affairs Population List can be directed to: Strategic Policy and Planning Branch Alberta Municipal Affairs 17th Floor, Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: (780) 427-2225 Fax: (780) 420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 780-420-1016 To be connected toll-free in Alberta, first dial 310-0000. - Page ii - 2017 Municipal Affairs Population List Table of Contents Introduction -

Communities Within Specialized and Rural Municipalities (May 2019)

Communities Within Specialized and Rural Municipalities Updated May 24, 2019 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] COMMUNITIES WITHIN SPECIALIZED AND RURAL MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES COMMUNITY STATUS MUNICIPALITY Abee Hamlet Thorhild County Acadia Valley Hamlet Municipal District of Acadia No. 34 ACME Village Kneehill County Aetna Hamlet Cardston County ALBERTA BEACH Village Lac Ste. Anne County Alcomdale Hamlet Sturgeon County Alder Flats Hamlet County of Wetaskiwin No. 10 Aldersyde Hamlet Foothills County Alhambra Hamlet Clearwater County ALIX Village Lacombe County ALLIANCE Village Flagstaff County Altario Hamlet Special Areas Board AMISK Village Municipal District of Provost No. 52 ANDREW Village Lamont County Antler Lake Hamlet Strathcona County Anzac Hamlet Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo Ardley Hamlet Red Deer County Ardmore Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87 Ardrossan Hamlet Strathcona County ARGENTIA BEACH Summer Village County of Wetaskiwin No. 10 Armena Hamlet Camrose County ARROWWOOD Village Vulcan County Ashmont Hamlet County of St. Paul No. 19 ATHABASCA Town Athabasca County Atmore Hamlet Athabasca County Balzac Hamlet Rocky View County BANFF Town Improvement District No. 09 (Banff) BARNWELL Village Municipal District of Taber BARONS Village Lethbridge County BARRHEAD Town County of Barrhead No. 11 BASHAW Town Camrose County BASSANO Town County of Newell BAWLF Village Camrose County Beauvallon Hamlet County of Two Hills No. 21 Beaver Crossing Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87 Beaver Lake Hamlet Lac La Biche County Beaver Mines Hamlet Municipal District of Pincher Creek No. 9 Beaverdam Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. -

City of Edmonton Annexation Application (March 2018). Appendix

CITY OF EDMONTON ANNEXATION APPLICATION APPENDIX 11.0 MEDIA MARCH 2018 CITY OF EDMONTON ANNEXATION APPLICATION APPENDIX 11: MEDIA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 8 2. NEWS ARTICLES 8 2.1. 2013 8 2.1.1. Global News Edmonton “Edmonton wants to annex 15,600 hectares of Leduc County, including airport” (March 5, 2013) 8 2.1.2. CTV News “City Starting Process to Annex Lands South of Edmonton, Including Airport” (March 5, 2013) 9 2.1.3. CBC News Edmonton “Edmonton looks to annex part of Leduc County” (March 5, 2013) 11 2.1.4. CTV News “Leduc County, Beaumont, Farmers Planning to Push Back Against Annexation” (March 6, 2013) 12 2.1.5. Global News Edmonton “Neighbouring municipalities defend land in light of Edmonton’s annexation plans” (March 6, 2013) 15 2.1.6. Leduc County Open Letter to Residents “Leduc County Residents and Businesses: Council Responds to City of Edmonton’s Proposed Annexation of 38,000 Acres” (March 12, 2013) 18 2.1.7. CTV News “Leduc County Responds to City of Edmonton’s Annexation Plan” (March 13, 2013) 21 2.1.8. Global News Edmonton “Leduc County wants Edmonton to end its ‘heavy handed’ annexation bid” (March 28 2013) 23 2.1.9. Global News Edmonton “City of Edmonton moving forward with Leduc County annexation plan” (November 8 2013) 25 2.1.10. Metro Edmonton “Leduc County mayor feels snubbed by Edmonton in looking land takeover” (November 8) 29 2.1.11. iNews “City launching annexation open houses” (November 8) 30 2.1.12. The Edmonton Sun “Land deal in works; Leduc promised annexation compensation” (November 9) 31 2.1.13. -

Living in Edmonton

LIVING I N EDMONTON A HANDY GUIDE TO WORK AT BioWare EDMONTON MAIN MENU EDMONTON FACTS ACCOMODATIONS TRANSPORTATION CULTURE & FUN BIOWARE PHOTOBOOTH INTRO We would like to thank you for your interest in BioWare, a division of EA. We know working in another country can be a challenge, but it can also be a unique opportunity to get to know a new place, culture, and people and have a great amount of new experiences. This guide has useful information about various topics that should answer many of your questions, but feel free to contact your recruiter to address any questions or concerns you may have. EDMONTON FACTS COST OF LIVING We imagine that you are wondering if your income will be enough to get by in Edmonton. Below you can find some examples of regular consumption products along with their average prices in the city. Lunch: $12-$15 Cup of cappuccino: $4.00 1 pint of beer (bar): $5.00 Drink (bar): $6.00 Milk (1 L): $2.15 Beefsteak (1lbs): $12.00 Bread loaf: $2.50 Pasta (packet): $3.00 Bag of chips: $2.00 Roasted chicken: $10.00 Can of Coke: 1.50 Chocolate bar: $1.50 Gyms $30-$60 Movie ticket: $13.00 Amusement Park: $20-$40 FINDING ACCOMODATIONS It is highly recommended to start your house hunting and checking out all other amenities over the internet. Below you can find some websites that could prove useful in your search. Useful Links Housing Family Resources City information Padmapper Public Schools General information Rent Edmonton Catholic Schools Edmonton Tourism Edmonton Kijiji Childcare Discover Edmonton Realtor.ca Child Friendly Immigration Alberta Craigslist Health Care Services Edmonton Public Library Environment Telephone Find a Doctor Edmonton Recycling Hospitals Travel Alberta Video Rogers Telus Pets Bell Fido General Info Edmonton Humane Internet/Cable Society Vets & Pet Hospitals Bell Pet Licences Telus Shaw Energy Epcor Enmax EDMONTON BY DISTRICTS 1 – North West 2 – North East 2 · A suburban area of Edmonton.