Eleanor Dare Stone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

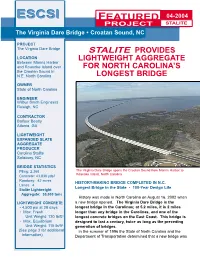

FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT the MONTH STALITE the Virginia Dare Bridge ¥ Croatan Sound, NC

ESCSIESCSI FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT THE MONTH STALITE The Virginia Dare Bridge • Croatan Sound, NC PROJECT The Virginia Dare Bridge STALITE PROVIDES LOCATION LIGHTWEIGHT AGGREGATE Between Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island over FOR NORTH CAROLINA’S the Croatan Sound in N.E. North Carolina LONGEST BRIDGE OWNER State of North Carolina ENGINEER Wilbur Smith Engineers Raleigh, NC CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty Atlanta, GA LIGHTWEIGHT EXPANDED SLATE AGGREGATE PRODUCER Carolina Stalite Salisbury, NC BRIDGE STATISTICS Piling: 2,368 The Virginia Dare Bridge spans the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, North Carolina Concrete: 43,830 yds3 Roadway: 42 acres HISTORY-MAKING BRIDGE COMPLETED IN N.C. Lanes: 4 Longest Bridge in the State • 100-Year Design Life Stalite Lightweight Aggregate: 30,000 tons History was made in North Carolina on August 16, 2002 when LIGHTWEIGHT CONCRETE a new bridge opened. The Virginia Dare Bridge is the • 4,500 psi at 28 days longest bridge in the Carolinas; at 5.2 miles, it is 2 miles • Max. Fresh longer than any bridge in the Carolinas, and one of the Unit Weight: 120 lb/ft3 longest concrete bridges on the East Coast. This bridge is • Max. Equilibrium designed to last a century, twice as long as the preceding Unit Weight: 115 lb/ft3 generation of bridges. (See page 3 for additional In the summer of 1996 the State of North Carolina and the information) Department of Transportation determined that a new bridge was ESCSI The Virginia Dare Bridge 2 required to replace the present William B. Umstead Bridge con- necting the Dare County main- land with the hurricane-prone East Coast. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Outdoor Theatre in North Carolina Lagniappe

* Lagniappe *Lagniappe (lan-yap, lan yap ) n. An extra or unexpected gift or benefit. [Louisiana French] William Joseph Thomas, Assistant Director for Collections and Scholarly Communications, Joyner Library, East Carolina University From “The Lost Colony” to “Unto These Hills”: Outdoor Theatre in North Carolina ummertime is high season for outdoor dramas, and North Carolina has a rich history of Sthem. Many NC natives have at- tended a production of “The Lost Colony” in Manteo or “Unto These Hills” in Cherokee. Other outdoor dramas in our state include “Strike at the Wind,” in Pembroke; “Horn in the West,” in Boone; “Tom Dooley: A Wilkes County Legend,” in Wil- kesboro; “First for Freedom,” in Halifax; and “From this Day Forward,” in Valdese. Shakespeare has his place in North Carolina too, from Ashe- ville’s Montford Park Players to Wilm- ington’s Cape Fear Shakespeare. The first, and arguably best-known, of North Carolina’s outdoor dramas is “The Lost Colony.” Written by Pu- litzer prize-winning NC native Paul Figure 1: Andy Griffith in the The Lost Colony, 1950, from Joyner Library Digital Collections, Green to commemorate its 350th an- http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/34133. niversary, “The Lost Colony” tells the story of the intended settlement of Colony” has entertained millions of around Robeson County from 1864 1587 and subsequent disappearance audience members and provided op- to 1872.3 Written by NCCU profes- of the 117 English colonists, includ- portunity for some 5,000 actors, in- sor of drama Randolph Umberger, ing Virginia Dare, first English child cluding favorite North Carolina son “Strike at the Wind” was performed born in the New World.1 Opening Andy Griffith. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) J, UN1TEDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS___________ | NAME HISTORIC Lane's New Fort in Virginia/Cittie of Raleigh AND/OR COMMON ~ Fort Raleigh National Historic Site ( \\ ^f I____________ LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER North end of Roanoke Island; 1 mile east of William B. Umstead Memorial Bridge on U.S. 64. —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Manteo — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE North Carolina 37 Dare 055 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT ^.PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL 2L.PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -^.EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE XsiTE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE JCENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) National Park Service. Department of the Interior, Southeast Regional Office STREET 8» NUMBER 1895 Phoenix Boulevard CITY. TOWN STATE Atlanta VICINITY OF Georgia 30349 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Dare County Courthouse/Register of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Courthouse Building CITY, TOWN STATE Manteo North Carolina 27954 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS JCALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The boundaries of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site include 159 acres. However, most of this acreage is either developed area, being managed as a natural area or the Elizabethan Gardens maintained by the Garden Club of North Carolina. -

Cover, Summary and Table of Contents.Pdf

PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Summary S.1 Contacts Gregory J. Thorpe, Ph.D., Manager Project Development and Environmental Analysis Branch North Carolina Department of Transportation 1548 Mail Service Center Raleigh, North Carolina 27699‐1548 (919) 733‐3141 S.2 Type of Action This State Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) has been prepared for the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) in accordance with the requirements of the North Carolina State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA G.S. 113A, Article 1), for the purpose of evaluating the potential impacts of a proposed transportation improvement project. This is an informational document intended for use by both decision‐makers and the public. As such, it represents a disclosure of relevant environmental information concerning the proposed action. This document conforms to the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) guidelines that provide direction regarding implementation of the procedural provisions of SEPA/ National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The United States Army Corps of Engineers is serving in the role of Lead Federal Agency on this project. S.3 Brief Description of the Project The action proposed in this state‐funded Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) is located in northeastern North Carolina along a rural 27.3‐mile corridor of US 64 from east of Columbia in Tyrrell County to US 264 in Dare County (Chapter 1, Figure 1‐1 and Figure 1‐2). The project is located as shown on Figure S‐1. The NCDOT proposes to widen the existing road from a two‐lane highway to a four‐lane expressway and build a new four‐lane bridge over the Alligator River. -

Commonlit | Settling a New World: the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island

Name: Class: Settling a New World: The Lost Colony of Roanoke Island By National Park Service 2016 The Fort Raleigh National Historic Site is dedicated to the preservation of England’s first New World settlements, as well as the cultural legacy of Native Americans, European Americans, and African Americans who lived on Roanoke Island. In 1585 and 1587, England tried its hand at establishing a colonial presence in North America under the leadership of Sir Walter Raleigh. The attempts were failures on both accounts but they would come to form one of the most puzzling mysteries in early American history: the disappearance of the Roanoke colony. As you read, take notes on what circumstances or mistakes might have put the English settlers at a disadvantage in creating a lasting colony. [1] "About the place many of my things spoiled and broken, and my books torn from the covers, the frames of some of my pictures and maps rotted and spoiled with rain, and my armor almost eaten through with rust." - John White1 on the lost colony of Roanoke Island 1584 Voyage In the late sixteenth-century, England’s primary goal in North America was to disrupt Spanish "John White discovers the word "CROATOAN" carved at Roanoke's shipping. Catholic Spain, under the rule of Philip fort palisade" by Unknown is in the public domain. II,2 had dominated the coast of Central and South America, the Caribbean, and Florida for the latter part of the 1500s. Protestant England, under the rule of Elizabeth I,3 sought to circumvent4 Spanish dominance in the region by establishing colonies in the New World. -

The Nativist Lobby Three Faces of Intolerance

The Nativist Lobby Three Faces of Intolerance A Report from the Southern Poverty Law Center Montgomery, Alabama February 2009 The Nativist Lobby Three Faces of Intolerance By Heidi BeiricH • edited By Mark Potok the southern poverty law center is a nonprofit organization that combats hate, intolerance and discrimination through education and litigation. Its Intelligence Project, which prepared this report and also produces the quarterly investigative magazine Intelligence Report, tracks the activities of hate groups and the nativist movement and monitors militia and other extremist anti- government activity. Its Teaching Tolerance project helps foster respect and understanding in the classroom. Its litigation arm files lawsuits against hate groups for the violent acts of their members. MEDIA AND GENERAL INQUIRIES Mark Potok, Editor Heidi Beirich Southern Poverty Law Center 400 Washington Ave., Montgomery, Ala. (334) 956-8200 www.splcenter.org • www.intelligencereport.org • www.splcenter.org/blog This report was prepared by the staff of the Intelligence Project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. The Center is supported entirely by private donations. No government funds are involved. © Southern Poverty Law Center. All rights reserved. southern poverty law center Table of Contents Preface 4 The Puppeteer: John Tanton and the Nativist Movement 5 FAIR: The Lobby’s Action Arm 9 CIS: The Lobby’s ‘Independent’ Think Tank 13 NumbersUSA: The Lobby’s Grassroots Organizer 18 southern poverty law center Editor’s Note By Mark Potok Three Washington, D.C.-based immigration-restriction organizations stand at the nexus of the American nativist movement: the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS), and NumbersUSA. -

We've Wondered, Sponsored Two Previous Expeditions to Roanoke Speculated and Fantasized About the Fate of Sir Island

/'\ UNC Sea Grant June/July, 7984 ) ,, {l{HsT4IIHI'OII A Theodor de Bry dtawin! of a John White map Dare growing up to become an Indian princess. For 400 yearS, Or, the one about the Lumbee Indians being descendants of the colonists. Only a few people even know that Raleigh we've wondered, sponsored two previous expeditions to Roanoke speculated and fantasized about the fate of Sir Island. Or that those expeditions paved the way Walter Raleigh's Lost Colony. What happened to for the colonies at Jamestown and Plymouth. the people John White left behind? Historians This year, North Carolina begins a three-year and archaeologists have searched for clues. And celebration of Raleigh's voyages and of the people still the answers elude us. who attempted to settle here. Some people have filled in the gaps with fic- Coastwatc.tr looks at the history of the Raleigh tionalized.accounts of the colonists' fate. But ex- expeditions and the statewide efforts to com- perts take little stock in the legend of Virginia memorate America's beginnings. In celebration of the beginning an July, the tiny town of Manteo will undergo a transfor- Board of Commissioners made a commitment to ready the I mation. In the middle of its already crowded tourist town for the anniversary celebration, says Mayor John season, it will play host for America's 400th Anniversary. Wilson. Then, the town's waterfront was in a state of dis- Town officials can't even estimate how many thousands of repair. By contrast, at the turn of the century more than people will crowd the narrow streets. -

Foundation Document Overview, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Fort Raleigh National Historic Site North Carolina Contact Information For more information about the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, contact: [email protected] or (252) 473-2111 or write to: Superintendent, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, 1401 National Park Drive, Manteo, NC 27954 Purpose Significance and Fundamental Resources and Values Significance statements express why Fort Raleigh National Historic Site resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • The park preserves the site on Roanoke Island where English explorers attempted to create England’s first colonial settlement in the New World in 1585–1587. • Fort Raleigh National Historic Site is the birthplace of Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the New World. FORT RALEIGH NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE • Fort Raleigh National Historic Site preserves archeological preserves and interprets the site of the evidence of the first English colonization efforts, and first English Colony in the New World, is supports research on the history and archeology of the the site of the theatrical production, historic site and the associated peoples and events to reveal The Lost Colony, and interprets the information on the Roanoke voyages and resolve the mystery historical events of the the history of the of the lost colony of 1587. -

Tar Heel Junior Historian

by Sandra Boyd* More than four hundred years ago, and children. Also aboard were two Indians, Europeans wanted to set up Manteo and Wanchese, who had gone to colonies in the New World. For England with Raleigh's previous expedition them, the New World meant the present- and were returning to their home. The pilot day continents of North was a Spaniard, Simon Fernando, and the and South America. What challenging times those must have been! Sir Walter Raleigh, an adventurous English gentleman, sent a group of men to explore the New World. A later expedition established a settlement on Roanoke Island, on the North Carolina coast. In 1586, after enduring winter hardships, lack of food, and disagreements with the Indians, survivors of this colony returned home to England with Sir Francis Drake. Then Raleigh decided to send a second group of colonists. On The baptism of Virginia Dare. April 26,1587, a small fleet set sail from England, hoping to establish governor of the new colony was John White. the first permanent English settlement in the Among the colonists were Governor White's New World. daughter, Eleanor, and her husband, This second group of colonists differed Ananias Dare. The voyage took longer than from the first because it included not only the usual six weeks, and the ships finally men but also women and children. It would anchored off Roanoke Island on July 22. be a permanent colony. The little fleet Once the colonists landed, they began consisted of the ship Lyon, a flyboat (a fast, repairing the houses already there and flat-bottomed boat capable of maneuvering started building new homes. -

Manteo Harbor Report

A CULTURAL RESOURCE EVALUATION OF SUBMERGED LANDS AFFECTED BY THE 400TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION Manteo, North Carolina Conducted By Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources Richard W. Lawrence, Head Leslie S. Bright Mark Wilde-Ramsing Report Prepared by Mark Wilde-Ramsing November, 1983 Abstract Field investigations of the submerged bottom lands at Manteo, North Carolina were carried out by the Underwater Archaeology Branch, Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources. The purpose of these investigations was to identify historically and/or archaeologically significant cultural materials lying within the area to be affected by construction of a bridge and canal system and berthing area proposed for the 400th Anniversary Celebration (1984 to 1987) on Roanoke Island. Initially, a systematic survey of the project area was performed using a proton precession magnetometer to isolate magnetic disturbances, any of which might be generated by cultural material. Following this, a diving and probing search was conducted on isolated magnetic targets to determine the source. With the exception of the remains of a sunken vessel, Underwater Site #0001ROS, all magnetic disturbances were attributed to cultural debris of recent origin (twentieth century) and were determined historically and archaeologically insignificant. Recommendations for the sunken vessel located on the south side of the proposed berthing area are (1) complete avoidance of the site during construction activities, or (2) further -

US History- Sweeney

©Java Stitch Creations, 2015 Part 1: The Roanoke Colony-Background Information What is now known as the lost Roanoke Colony, was actually the third English attempt at colonizing the eastern shores of the United States. Following through with his family's thirst for exploration, Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Sir Walter Raleigh a royal charter in 1584. This charter gave him seven years to establish a settlement, and allowed him the power to explore, colonize and rnle, in return for one-fifth of all the gold and silver mined in the new lands. Raleigh immediately hired navigators Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to head an expedition to the intended destination of the Chesapeake Bay area. This area was sought due to it being far from the Spanish-dominated Florida colonies, and it had milder weather than the more northern regions. In July of that year, they landed on Roanoke Island. They explored the area, made contact with Native Americans, and then sailed back to England to prove their findings to Sir Walter Raleigh. Also sailing from Roanoke were two members oflocal tribes of Native Americans, Manteo (son of a Croatoan) and Wanchese (a Roanoke). Amadas' and Barlowe's positive report, and Native American assistance, earned the blessing of Sir Walter Raleigh to establish a colony. In 1585, a second expedition of seven ships of colonists and supplies, were sent to Roanoke. The settlement was somewhat successful, however, they had poor relations with the local Native Americans and repeatedly experienced food shortages. Only a year after arriving, most of the colonists left.