The Unconstitutional Trial of Mary Surratt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Confession of George Atzerodt

The Confession of George Atzerodt Full Transcript (below) with Introduction George Atzerodt was a homeless German immigrant who performed errands for the actor, John Wilkes Booth, while also odd-jobbing around Southern Maryland. He had been arrested on April 20, 1865, six days after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth. Booth had another errand boy, a simpleton named David Herold, who resided in town. Herold and Atzerodt ran errands for Booth, such as tending horses, delivering messages, and fetching supplies. Both were known for running their mouths, and Atzerodt was known for drinking. Four weeks before the assassination, Booth had intentions to kidnap President Lincoln, but when his kidnapping accomplices learned how ridiculous his plan was, they abandoned him and returned to their homes in the Baltimore area. On the day of the assassination the only persons remaining in D.C. who had any connection to the kidnapping plot were Booth's errand boys, George Atzerodt and David Herold, plus one of the key collaborators with Booth, James Donaldson. After David Herold had been arrested, he confessed to Judge Advocate John Bingham on April 27 that Booth and his associates had intended to kill not only Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward, but Vice President Andrew Johnson as well. David Herold stated Booth told him there were 35 people in Washington colluding in the assassination. This information Herold learned from Booth while accompanying him on his flight after the assassination. In Atzerodt's confession, this band of assassins was described as a crowd from New York. -

How Did Booth Break His

STATE YOUR CASE (No. 2), John Elliott: How Did John Wilkes Booth Break His Leg? I believe that John Wilkes Booth did not break his leg when jumping from the balustrade to the stage at Ford’s Theatre. I support Michael Kauffman’s theory that Booth broke his Fibula when his horse fell on him after he crossed in to Maryland. First I will refute the diary entry Booth wrote during his escape, claiming he broke his leg in jumping. Booth’s version of events is filled with exaggerated claims that were written in response to newspaper articles calling him a coward. Next, I will present the first eyewitness accounts taken in the early days after the assassination that state John Wilkes Booth ran or rushed across the stage after jumping from the box. Surely a man who had just broken his leg would show some signs of pain or would limp after breaking his leg. Last, I will present the evidence that I believe shows JWB broke his leg when his horse fell on him. This includes more eyewitness accounts and medical opinions. Sources: We Saw Lincoln Shot Timothy S. Good American Brutus Mike Kauffman The Lincoln Assassination/The Evidence Edwards and Steers Jr. Booth’s Diary Entry History books tell us that John Wilkes Booth broke his leg while jumping from the balustrade of President Lincoln’s box to the stage at Ford’s Theatre. This is the most commonly held belief because John Wilkes Booth wrote that it happened that way. But should we take his word for it? A closer examination of his diary entry shows that he tried to paint a more daring and heroic image of himself during what he believed to be his crowning achievement. -

The Assassination 1 of 2 a Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy

5-2 The Assassination 1 of 2 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy The Assassination Lincoln Assassination. Clipart ETC. 18 July 2008. Educational Technology Clearinghouse. University of South Florida. <http://etc.usf.edu/clipart> March 17, 1865 John Wilkes Booth’s plot to kidnap Lincoln is foiled by Lincoln’s failure to show up at the soldiers’ hospital where Booth planned to carry out the kidnapping. April 14,1865 Booth fires his derringer the President while Lincoln, his wife Mary Todd Lincoln, Maj. Henry R. Rathbone, and his fiancée Clara Harris are in a private box in Ford’s Theater viewing a special performance of Our American Cousin. Entering through the President's left ear, the bullet lodges behind his right eye, leaving him paralyzed. Booth leaps from the box on to the stage, declaring “Sic simper tyrannis” and breaking his right fibula. Nearly simultaneously, Lewis Paine twice slashes Secretary of State William Henry Seward’s throat while the Secretary lies in bed recovering from a carriage accident. A metal surgical collar prevents the attack from accomplishing its deadly objective. Believing his attempt successful, Paine fights his way out of the mansion. Dr. Charles Leale examines the President. Lincoln is moved to a boarding house, now called the Peterson House, across Office of Curriculum & Instruction/Indiana Department of Education 09/08 This document may be duplicated and distributed as needed. 5-2 The Assassination 2 of 2 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy from the theater on 10th Street. Co-conspirator George Atzerodt fails to carry out the plan to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson. -

The Lincoln Assassination

The Lincoln Assassination The Civil War had not been going well for the Confederate States of America for some time. John Wilkes Booth, a well know Maryland actor, was upset by this because he was a Confederate sympathizer. He gathered a group of friends and hatched a devious plan as early as March 1865, while staying at the boarding house of a woman named Mary Surratt. Upon the group learning that Lincoln was to attend Laura Keene’s acclaimed performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, Booth revised his mastermind plan. However it still included the simultaneous assassination of Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. By murdering the President and two of his possible successors, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to throw the U.S. government into disarray. John Wilkes Booth had acted in several performances at Ford’s Theatre. He knew the layout of the theatre and the backstage exits. Booth was the ideal assassin in this location. Vice President Andrew Johnson was at a local hotel that night and Secretary of State William Seward was at home, ill and recovering from an injury. Both locations had been scouted and the plan was ready to be put into action. Lincoln occupied a private box above the stage with his wife Mary; a young army officer named Henry Rathbone; and Rathbone’s fiancé, Clara Harris, the daughter of a New York Senator. The Lincolns arrived late for the comedy, but the President was reportedly in a fine mood and laughed heartily during the production. -

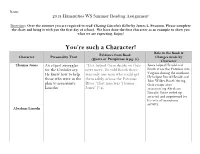

You're Such a Character!

Name:_____________________________________________ 2018 Humanities WS Summer Reading Assignment Directions: Over the summer you are required to read Chasing Lincoln’s Killer by James L. Swanson. Please complete the chart and bring it with you the first day of school. We have done the first character as an example to show you what we are expecting. Enjoy! You’re such a Character! Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Thomas Jones An expert smuggler “Cox helped them decide on their Jones helped Herold and for the Confederacy. next move. He told Booth there Booth cross the Potomac into He knew how to help was only one man who could get Virginia during the manhunt. those who were in the them safely across the Potomac He helped David Herold and John Wilkes Booth during plan to assassinate River. That man was Thomas their escape after Lincoln. Jones” (74). assassinating Abraham Lincoln. Jones ended up arrested and imprisoned for his acts of treasonous activity. Abraham Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Wilkes Booth Edwin Stanton George Atzerodt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Garrett John Surratt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Mary Surratt Mary Todd Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. -

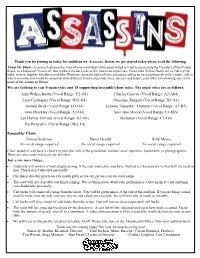

We Are Looking to Cast 9 Main Roles and 15 Supporting/Ensemble/Choir Roles

Thank you for joining us today for auditions for Assassins. Before we get started today please read the following: About the Show: Assassins lays bare the lives of nine individuals who assassinated or tried to assassinate the President of the United States, in a historical "revusical" that explores the dark side of the American experience. From John Wilkes Booth to Lee Harvey Os- wald, writers, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman, bend the rules of time and space, taking us on a nightmarish roller coaster ride in which assassins and would-be assassins from different historical periods meet, interact and inspire each other to harrowing acts in the name of the American Dream. We are looking to cast 9 main roles and 15 supporting/ensemble/choir roles. The main roles are as follows: John Wilkes Booth (Vocal Range: F2-G4) Charles Guiteau (Vocal Range: A2-Ab4) Leon Czologosz (Vocal Range: G#2-G4) Giuseppe Zangara (Vocal Range: B2-A4) Samuel Byck (Vocal Range: D3-G4) Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme (Vocal Range: A3-B5) John Hinckley (Vocal Range: A2-G4) Sara Jane Moore (Vocal Range: F3-Eb5) Lee Harvey Oswald (Vocal Range: A2-G4) Balladeer (Vocal Range: C3-G4) The Proprietor (Vocal Range: Gb2-F4) Ensemble/ Choir: Emma Goldman David Herold Billy Moore No vocal range required No vocal range required No vocal range required Choir members will have a chance to play the roles of the presidents, tourists, news reporters, bystanders, or photographers. There are also some solo parts for the choir. Just a few more things… Auditions will consist of your prepared song. -

The Flimsy Case Against Mary Surratt: the Judicial Murder of One

The Flimsy Case Against Mary Surratt: The Judicial Murder of One of the Accused Lincoln Assassination Conspirators Michael T. Griffith 2019 @All Rights Reserved On June 30, 1865, an illegal military tribunal found Mrs. Mary Surratt guilty of conspiring with John Wilkes Booth and others to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln, and sentenced her to death by hanging. Despite numerous appeals to commute her sentence to life in prison, she was hung seven days later on July 7. She was the first woman ever to be executed by the federal government. The evidence that the military commission used as the basis for its verdict was flimsy and entirely circumstantial. Even worse, the War Department’s prosecutors withheld evidence that indicated Mrs. Surratt did not know that Booth intended to shoot President Lincoln. The prosecutors also refused to allow testimony that would have seriously impeached one of the two chief witnesses against her. Mary Surratt John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln’s assassin. He shot President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington on April 14, 1865. The military tribunal claimed that Mary Surratt: * Knew about the assassination plot and failed to report it * On April 11, 1865, told John Lloyd that the “shooting irons” (rifles) that had been delivered to him would be needed soon 1 * An April 14, the day of the assassination, gave Lloyd a package from Booth and told him to have the rifles ready that night * Falsely claimed that she did not recognize Lewis Payne (Lewis Powell) when he showed up at her boarding house on April 17 * Falsely claimed that her youngest son, John Surratt, was not in Washington on the day of the assassination Two Plots: Kidnapping and Assassination Before we begin to examine the military commission’s case against Mary Surratt, we need to understand that Booth initiated two separate plots against Lincoln. -

Look Inside Women’S History Month with a Luncheon at Newton White Mansion

THE MARYLAND-NATIONAL CAPITAL PARK AND PLANNING COMMISSION EMPLOYEE NEWS A UpdateBI-COUNTY COMMISSION SERVING MONTGOMERY AND PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTIES VOLUME XXIV • ISSUE 4 WWW.MNCPPC.ORG APRIL 2015 M-NCPPC Celebrates National Look Inside Women’s History Month with a Luncheon at Newton White Mansion Staff and guests gathered at Newton White Man- Prince George's Planning Updates sion on Monday, March 16 to celebrate Women's History Citizens' Handbook Month. The event began with Executive Director Patricia .............................................................page 3 Colihan Barney's opening remarks and a welcome by M-NCPPC Vice-Chair Casey Anderson. Commissioner Year-End Purchasing Reminders Marye Wells-Harley performed Mistress of Ceremonies .............................................................page 3 duties. Attendees were treated to lunch and, in keep- ing with the national theme of "Weaving the Stories of Montgomery Parks In-Service Training Women's Lives," guests got to enjoy a weaving demon- stration and interactive weaving activities. Presentations .............................................................page 4 were given by A. Shuanise Washington, Prince George’s County Commissioner, Natali Fani-Gonzalez, Montgom- Health and Benefits Update ery County Commissioner and Maureen Dougherty, Ph.D., ........................................................pages 6-7 Visiting Professor and Program Coordinator, Community College of Baltimore County (Catonsville). ERS LifeTimes The committee provided interactive displays for at- ...........................................................page 10 tendees to experience various types of weaving looms. Participants were invited to write their names on strips of fabric, which were then woven into a shawl on a giant community loom. The shawl was presented to Commis- See Women's History, page 2 The deadline for submissions to the next issue of Update is close of business Friday, May 1. -

Mary Surratt: the Unfortunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita History Class Publications Department of History 2013 Mary Surratt: The nforU tunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death Leah Anderson Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Leah, "Mary Surratt: The nforU tunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death" (2013). History Class Publications. 34. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history/34 This Class Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Class Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Surratt: The Unfortunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death Leah Anderson 1 On the night of April 14th, 1865, a gunshot was heard in the balcony of Ford’s Theatre followed by women screaming. A shadowy figure jumped onto the stage and yelled three now-famous words, “Sic semper tyrannis!” which means, “Ever thus to the tyrants!”1 He then limped off the stage, jumped on a horse that was being kept for him at the back of the theatre, and rode off into the moonlight with an unidentified companion. A few hours later, a knock was heard on the door of the Surratt boarding house. The police were tracking down John Wilkes Booth and his associate, John Surratt, and they had come to the boarding house because it was the home of John Surratt. An older woman answered the door and told the police that her son, John Surratt, was not at home and she did not know where he was. -

The History Page: Lincoln's Female 'Assassin'

The History Page: Lincoln’s female ‘assassin’ Housekeeper Mary Surratt is hanged for conspiracy on flimsy evidence Photo: Corbis By Rob Ogden, Saturday, August 6, 2011, The Daily, http://bit.ly/ogbWUD More than 1,000 people watched as Mary Surratt, a handsome widow and mother of three, stood on a trapdoor with a noose around her neck. Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated just three months earlier, and Surratt had been convicted of conspiring to kill him. Despite her pleas of innocence, U.S. authorities took her to the gallows, put a noose around her neck and pulled the lever. Surratt became the first woman executed by the U.S. government on July 7, 1865. Though convicted of treason, she insisted on her innocence until her death, and evidence suggests that she was, in fact, uninvolved with the Lincoln assassination plot. Tragedy had followed Mary her whole life, beginning with her father’s death in 1825, when she was 2 years old. Her mother ran the family affairs well and put Mary through Catholic boarding school near her home in Waterloo, Md. She grew into a comely young woman with dark hair, high cheekbones and large, mournful eyes. She befriended the local priest and became devoutly Catholic. Perhaps for lack of fatherly guidance, she married at 16 to a man named John Surratt, who had a troublesome background including financial problems and an illegitimate child he’d fathered the year before. But things started off well enough: Between 1841 and 1844, Mary had three children: Isaac, Elizabeth and John Jr. -

Robert Purdy, 3Rd WV Inf/6Th WV Cav & Potomac

ROBERT PURDY, CIVIL WAR SOLDIER FROM MARSHALL COUNTY Written by Linda Cunningham Fluharty, May 21, 2012 Eric McFadden sent a file (which follows) about Civil War soldier, Robert C. Purdy, of Moundsville, Marshall County. Purdy had some connection to the President Lincoln Conspiracy-Assassination trials and Eric's records are from that proceeding. At first, it seemed that the Robert Purdy was the man in the 3rd West Virginia that subsequently became the 6th West Virginia Cavalry, but evidence now indicates that the Robert C. Purdy related to the Assassination Trial enlisted in the 2nd Maryland Cavalry and was transferred to Company "M" of the Maryland 1st Regiment Potomac Home Brigade. Since only one Robert C. Purdy has been found, perhaps the same man was in both organizations. Service Records of Robert C. Purdy exist for both regiments. Robert C. Purdy in Company "I" of the 3rd Infanty/6th Cavalry was 41 when he enlisted 11 Dec 1861 in the 3rd Infantry. He was born in West Chester, NY. He received a Medical Discharge 11 July 1863. This is his family in the 1860 Census of Marshall County: PURDY (551) Robt. C...39-wm...painter...NY Minerva...38-wf...OH William...20-wm...VA Mary E...18-wf...VA Henrietta M...16-wf...OH Martha N...12-wf...OH Robert C Purdy - "alias Ashley," according to the Service Record - in Company "M" of the 1st Regiment Potomac Home Brigade, Maryland was 23 years old (one page says 33), 5'10" tall, born in Marshall County, when he enlisted 9 Sep 1864 at Cumberland, MD to serve two years. -

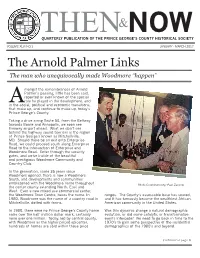

The Arnold Palmer Links the Man Who Unequivocally Made Woodmore “Happen”

&NOW THENQUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XLVI NO.1 JANUARY - MARCH 2017 The Arnold Palmer Links The man who unequivocally made Woodmore “happen” mongst the remembrances of Arnold Palmer’s passing, little has been said, reported or even known of the special role he played in the development, and inA the social, political and economic transitions, that make up, and continue to make up, today’s Prince George’s County. Taking a drive along Route 50, from the Beltway towards Bowie and Annapolis, we soon see Freeway airport ahead. What we don’t see behind the highway sound barriers is the region of Prince George’s known as Mitchellville, MD. Should there be an exit onto Enterprise Road, we could proceed south along Enterprise Road to the intersection of Enterprise and Woodmore Road. Enter through the security gates, and arrive inside of the beautiful and prestigious Woodmore Community and Country Club. In the generation, some 35 years since Woodmore opened, there is now a Woodmore South, and developments and communities emblazoned with the Woodmore name throughout Photo Contributed by: Paul Zanecki the center county extending North, East and West. Even a new mixed use commercial center, the Woodmore Town Centre, bears the name. In ranges. The County’s assessable base has soared, 1980, Woodmore was the name of a country road in and it has famously become the wealthiest African- Mitchellville, dotted with farms. American community in the United States. In 1980, there were no Prince George’s County home Was this dynamic change a natural demographic sales over the half million dollar mark, certainly evolution, or did some catalytic or transformative none over one million.