The Art of Crime: the Application of Literary Proceeds of Crime Confiscation Legislation to Visual Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heat and Light

FREE SEPTEMBER 2014 BOOKS MUSIC FILM EVENTS HEAT AND LIGHT Ceridwen Dovey on Ellen van Neerven’s debut work of fiction page 6 THE CHILDREN ACT Brigid Mullane on Ian McEwan’s new novel page 9 THE READINGS NEW AUSTRALIAN WRITING AWARD The shortlist announced page 12 NEW IN SEPTEMBER SONYA HELEN LORELEI WES ROBERT HARTNETT GARNER VASHTI ANDERSON PLANT $29.99 $32.99 $27.99 $39.95 $21.95 page 7 $29.99 page 14 $32.95 page 22 page 14 page 21 You’ve looked after Dad’s reading needs, now look after your own. The Bone Clocks A mind-stretching, kaleidoscopic, globetrotting feast. When The Night Comes An evocative and gently told story about how kindness can change lives. The Paying Guests Vintage Sarah Waters – excruciating tension and real tenderness. The Secret Place A breathtakingly suspenseful disentangling of the truth. Get the whole story at hachette.com.au READINGS MONTHLY SEPTEMBER 2014 3 News INDIGENOUS LITERACY DAY This year, Indigenous Literacy Day is on Wednesday 3 September. The Indigenous Literacy Foundation (ILF) aims to raise literacy levels and improve the opportunities of Indigenous Australians living in remote and isolated regions. The foundation does this through a free book supply program that goes to over 200 organisations and communities, and through a community publishing project that publishes books and stories, largely written by children. The foundation needs your support to help raise funds to buy books and literacy resources for children in these communities. Readings will donate 10% of sales from our shops on this day to the Indigenous Literacy Foundation. -

Adam CULLEN Born Sydney 1965, Died 2012

Adam CULLEN Born Sydney 1965, died 2012 Adam Cullen was an Australian artist, most known for winning the Archibald Prize in 2000 with a portrait of actor David Wenham. He was also known for his controversial subjects or work. His style has at times been called by some critics as simplistic, crude, adolescent or puerile, though he is regarded one of Australia's most collectible contemporary artists. Cullen's studio was located at Wentworth Falls, in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales. He had stated that he had painted to the music of punk bands such as the Meat Puppets, Black Flag and the Butthole Surfers. Cullen painted such things as dead cats, 'bloodied' kangaroos, headless women and punk men, many of which represent what he termed "Loserville". The artist used a highly personal visual language to address a broad range of topics including crime, masculinity and cowboy culture. He merged high and low cultural influences in works which are defined by their iridescent colours and bold gestural marks. His works combine irreverent humour with an astute sensitivity to society. Cullen’s work is held in collections including the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth; Monash University, Melbourne; and Griffith University, Brisbane. I HEART PAINT curated by Iain Dawson gallery.begavalley.nsw.gov.au Adam CULLEN Mare from Kildare 2004 acrylic on canvas 102 x 76cm Private Collection Adam CULLEN Auto Portrait 2005 acrylic on canvas 52 x 41cm Private Collection Adam CULLEN My Crackerjack 2004 acrylic on canvas 182 x 182cm Private Collection Adam CULLEN When she goes, I dress up 2003 acrylic on canvas 182 x 152cm Private Collection I HEART PAINT curated by Iain Dawson gallery.begavalley.nsw.gov.au Alesandro LJUBICIC Born 1986, Jajce, Bosnia and Herzegovina Lives and works Sydney, New South Wales Ljubicic studied at the National Art School in Sydney where he was involved in a number of exhibitions and Art awards between 2004 - 07. -

ADAM CULLEN Artist 1965-2012 ADAM WE HARDLY KNEW YOU

ADAM CULLEN Artist 1965-2012 ADAM WE HARDLY KNEW YOU It is just over a year since wellknown artist, Archibald Prize winner Adam Cullen was found dead at his cottage in Wentworth Falls aged just 46. The artist had achieved extraordinary heights as an artist and even had a hotel named after him, The Cullen Hotel in Melbourne. Much has been written about the artist and the man, critical and adulatory. What follows here is a glimpse of how this controversial artist was perceived in the Blue Mountains art community in the last years of his life — a life closely observed, as is the way in a village, and offering extreme polarities in opinion. A frisson ran through the Blue Mountains art community everyone. While describing Anita’s rape and murder as when in 2000 Adam Cullen came to town — imagine a ‘a disgusting crime’ Cullen also expressed sympathy for cowboy with pistols hugging both hips (he liked cowboys the murderers. ‘Things are more complex than the single and other masculine imagery). There was anticipation issue of rape and murder and associated crimes against at the prospect of meeting this art world curiosity and women – especially when art is involved.’ ‘I’ve painted seeing him around the traps. the killers of Anita Cobby because, as with all my work, I’m responding to information – information on all levels, Cullen and his then girlfriend Carrie Miller settled in this televisual and printed media. This is why the killers are of well-off Blue Mountains village - a community wellknown legitimate interest. In no way is my focus ignoring the plight for its artists - in a typical Mountains cottage with an of the victim. -

Travelling Showcase 2018 with Festival Favourites to Screen Across Regional Victoria

Travelling Showcase MIFF GOES ON THE ROAD FOR THE TRAVELLING SHOWCASE 2018 WITH FESTIVAL FAVOURITES TO SCREEN ACROSS REGIONAL VICTORIA MIFF Travelling Showcase, the Melbourne International Film Festival’s tour of regional Victoria returns from late August to November, featuring eight of the most talked about films of the 67th festival. Supported by the Victorian State Government, a varied series of weekend programs featuring Australian and international feature films and documentaries will take place in nine locations starting in Belgrave on 31 August, before moving on to Bairnsdale, Ballarat, Wangaratta, Bendigo, Geelong, Bright, Mansfield and Mildura. From a dramatically striking tale of two wildly different men who formed a unique and unlikely bond, to an exploration into the life of a world lauded pianist whose talents were overlooked at home in Australia, this year’s program features MIFF Premiere Fund-supported films Acute Misfortune, The Eulogy, Undermined: Tales from the Kimberley, Undertow and The Coming Back Out Ball Movie alongside uproarious new Aussie comedy The Merger, American star-studded rom-com Juliet, Naked and audacious crime drama American Animals. 2018 TRAVELLING SHOWCASE PROGRAM: Feature films Acute Misfortune (MIFF Premiere Fund-supported) – winner of The Age Critics’ Award for best Australian feature film, Daniel Henshall (Snowtown) stars as infamous Archibald Prize-winning artist Adam Cullen in a lyrical adaptation of The Saturday Paper editor Erik Jensen’s acclaimed biography. Starring Toby Wallace (Romper Stomper), Max Cullen (Love My Way) and Genevieve Lemon (The Dressmaker), Top of the Lake actor Thomas M. Wright makes his directorial feature debut weaving a striking tale of the bright young wunderkind writer and the brilliant yet deeply troubled artist. -

Annual Report 2015–16 © National Gallery of Australia 2016 All Rights Reserved

Annual Report 2015–16 © National Gallery of Australia 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. National Gallery of Australia Parkes Place, Canberra ACT 2600 GPO Box 1150, Canberra ACT 2601 Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Carla Da Silva Index by Sherrey Quinn Printed by New Millennium Print ISSN 1323 5192 nga.gov.au/aboutus/reports Cover: Tom’s Studio, the family activity room for Tom Roberts, supported by Tim Fairfax AC, February 2016. CONTENTS Letter of transmittal 5 About the NGA 6 Executive summary 9 Chair’s report 10 Director’s report 12 Snapshot 20 Performance summary 24 Performance statements 25 Engage, educate and inspire 27 Managing resources 35 Collect, share and digitise 37 Management and accountability 47 Governance 48 Corporate services 55 Statutory compliance 58 Appendices 59 Appendix A: Exhibitions 60 Appendix B: Publishing and papers 62 Appendix C: Acquisitions 66 Appendix D: Supporters 79 Appendix E: Legislative requirements 91 Appendix F: Index of requirements 95 Appendix G: Agency resource statement 96 Financial statements 97 Independent auditor’s report 98 Financial statements 100 Notes 105 Glossary 124 Index 126 NGA Annual Report 2015–16 3 Tables Table 1: Performance summary 2015–16 24 Table 2: Visitation 27 Table 3: Public programs 28 Table 4: School participation 30 Table 5: Online visits -

The Limits of Taste: Politics, Aesthetics, and Christ in Contemporary Australia Zoe Alderton

The Limits of Taste: Politics, Aesthetics, and Christ in Contemporary Australia Zoe Alderton Introduction This article argues that there is a tacit system of social values operating around the reception of mainstream, normative Christianity in Australian art. Christianity, although a revolutionary movement at its start, has been tied to notions of decency, respect, tradition, and stability since its institutionalisation by the Roman Empire. Additionally, religious imagery has always been of concern in this faith as it stands in relation to a commandment that warns against graven images. Religious art and Christianity have clashed wildly and radically at various times in the life of the Church, the iconoclastic period of the Byzantine Empire being one startling example amongst many of how much religious iconography matters. Similarly, religious art today, especially that which challenges institutionalised Christianity, is taken by many to be not only art bordering on blasphemy, but as an affront to dominant cultural values. This article employs examples from the Blake Prize for Religious Art (1951 to the present) as a case study for the increasingly common fear that contemporary Australian art is a site of declining morality. Focusing on recent artworks by Rodney Pople, Adam Cullen, and Luke Roberts, the boundaries of permissible Christian imagery will be explored. Art that is perceived as sexually deviant, too broadly „spiritual,‟ or ugly, appears to fail the test of acceptability. Headlines are guaranteed as religious commentators and outraged journalists lampoon and deride what is perceived to be irreligious art. Under the present spirit of reactionary journalism, the intended (and often fairly obvious) meaning behind contentious artworks is dismissed in favour of moral outrage at any image of Christianity that is deemed unorthodox.1 Jocularity, shock, and satirical elements are unfairly read as blasphemous whilst genuine social commentary and messages of compassion in the artworks are often ignored. -

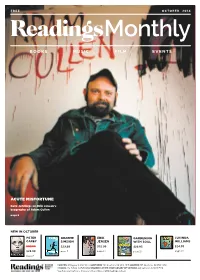

Books Music Film Events

FREE OCTOBER 2014 BOOKS MUSIC FILM EVENTS ACUTE MISFORTUNE Kate Jennings on Erik Jensen’s biography of Adam Cullen page 6 NEW IN OCTOBER PETER GRAEME ERIK GARDENING LUCINDA CAREY SIMSION JENSEN WITH SOUL WILLIAMS $32.99 $29.99 $32.99 $29.95 $24.95 $29.99 page 7 page 14 page 21 page 22 page 7 READINGS MONTHLY OCTOBER 2014 3 News 2-FOR-1 TICKET SPECIAL FOR Samson & Delilah and Ten Canoes. Don’t THE VICTOR HUGO EXHIBITION miss out on this wonderful opportunity If you haven’t had a chance to visit the to own a cut of Australian film history. magnificent Victor Hugo: Les Misérables Available from now until 31 October in all – From Page to Stage exhibition at the Readings shops and online at State Library of Victoria, then now is readings.com.au. Only while stocks last. your chance. We have a limited number of flyers offering 2-for-1 tickets to the 25% OFF LONELY PLANET exhibition available in each of our Spring is upon us, and what better time shops, redeemable at the State Library than now to begin planning for your next box office (offering a saving of $15). travel adventure. Whatever your travel Featuring rare items from the collections style – cruisy resort holidays, brave jaunts of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, in the jungle, deep desert explorations or Maisons de Victor Hugo, Musée Rodin just plain culture shock – Lonely Planet and Cameron Mackintosh, and including is brimming with inspiration to help you original drawings and watercolours by choose your next escape. -

FEATURE FILMS in COMPETITION Foxtel and Netflix Now All in One Place

2019 AACTA AWARDS PRESENTED BY FOXTEL FEATURE FILMS IN COMPETITION Foxtel and Netflix now all in one place ACUTE MISFORTUNE ANGEL OF MINE The flm adaptation of Erik Jensen's Divorced mother, Lizzie, an imbalanced biography of Adam Cullen is the story of the woman battling for custody of her son, has biographer and his subject as it descends her life turned upside down on crossing into a dependent and abusive relationship. paths with Lola, a child who she believes to be the daughter she lost seven years ago in PRODUCER Virginia Kay, Jamie Houge, a hospital fre. Unable to let her suspicions Liz Kearney, Thomas M Wright go, Lizzie stalks and befriends Lola's mother, DIRECTOR Thomas M Wright Claire, inching her way into Lola's life, to the SCREENWRITER Thomas M Wright, bewilderment of her family. Claire grows Erik Jensen suspicious on discovering that this strange LEAD ACTOR Daniel Henshall, Toby Wallace woman is systematically following her little girl, SUPPORTING ACTOR Max Cullen appearing everywhere. As Lizzie's obsession SUPPORTING ACTRESS Gillian Jones, heightens and her behaviour becomes Genevieve Lemon increasingly disturbing, Claire confronts her, CINEMATOGRAPHER Germain McMicking, which brings deeply buried secrets to the Stefan Duscio surface and the devastating truth is revealed. EDITOR Luca Cappelli COMPOSER Evelyn Ida Morris PRODUCER Brian Etting, Josh Etting, SOUND Chris Goodes, Steve Bond, Su Armstrong Cam Rees DIRECTOR Kim Farrant PRODUCTION DESIGNER Leah Popple SCREENWRITER Luke Davies, David Regal COSTUME DESIGNER Sophie -

SKIN PRESSEMEDDELELSE.Pdf

Another World Entertainment Saltum Allé 4 2770 Kastrup Jan Schmidt [email protected] 40 55 51 11 PRÆSENTERER Skin En film af Guy Nattiv Skin - 110 min – USA 2018 PRESSEVISNING mandag, den 7. oktober 2019, kl. 12.00 i Vester Vov Vov Danmarkspremiere torsdag, den 17. oktober 2019 i følgende biografer: Gloria Biograf, Vester Vov Vov, Valby Kino, Øst for Paradis, Værløse Bio m.fl. Another World Entertainment Saltum Allé 4 2770 Kastrup Jan Schmidt [email protected] 40 55 51 11 "ROMPER STOMPER" MØDER "AMERICAN HISTORY X" I HØJAKTUELT SPÆNDINGS- DRAMA INSTRUERET AF OSCAR-VINDENDE GUY NATTIV. SYNOPSIS: Bryon Widner, en af FBIs mest eftersøgte skinheads, lever et destruktivt liv med kroppen dækket af racistiske tatoveringer fra top til tå, som han får lov at bære som belønning for sine utallige brutale hadforbrydelser. Da han møder Julie og hendes tre unge døtre fra et tidligere forhold, vækker faderrollen følelser som ansvarlighed og kærlighed i ham, og giver ham et brændende ønske om at lægge sin gamle tilværelse bag sig. Det viser sig dog snart, at hans gamle venner ikke bryder sig om hans beslutning om at lægge sit liv om, og han må leve med dødstrusler og chikane fra sin gamle bande. Med hjælp fra FBI og SPLC får han hjælp til at forlade det neo-nazistiske miljø og får fjernet de mange tatoveringer, der skæmmer hans udseende i bytte for informationer om deres betydning – informationer, der resulterer i anholdelsen af hans tidligere bande. En brutal og nådesløs fortælling om racisme og ignorance, men også en fortælling om, at det aldrig er for sent at give slip på hadet og vende sig mod noget nyt. -

2019 Aacta Awards Presented by Foxtel

2019 AACTA AWARDS PRESENTED BY FOXTEL – FEATURE FILM IN COMPETITION – ACUTE MISFORTUNE The film adaptation of Erik Jensen's biography of Adam Cullen is the story of the biographer and his subject as it descends into a dependent and abusive relationship. Director: Thomas M Wright Producers: Virginia Kay, Jamie Houge, Liz Kearney, Thomas M Wright Writer: Thomas M Wright , Erik Jensen Editor: Luca Campbell Sound: Chris Goodes, Steve Bond, Cam Rees Cinematographer: Germain McMicking, Stefan Duscio Original Music Score: Evelyn Ida Morris Production Designer: Leah Popple Costume Design: Sophie Fletcher Lead Actor: Daniel Henshall, Toby Wallace Supporting Actor: Max Cullen Supporting Actress: Gillian Jones, Genevieve Lemon Casting Director: Jane Norris, Holly Anderson ANGEL OF MINE Divorced mother, Lizzie, an imbalanced woman battling for custody of her son, has her life turned upside down on crossing paths with Lola, a child who she believes to be the daughter she lost seven years ago in a hospital fire. Unable to let her suspicions go, Lizzie stalks and befriends Lola's mother, Claire, inching her way into Lola's life, to the bewilderment of her family. Claire grows suspicious on discovering that this strange woman is systematically following her little girl, appearing everywhere. As Lizzie's obsession heightens and her behaviour becomes increasingly disturbing, Claire confronts her, which brings deeply buried secrets to the surface and the devastating truth is revealed. Director: Kim Farrant Producer: Brian Etting, Josh Etting, Su Armstrong Writer: Luke Davies, David Regal Editor: Jack Hutchings Sound: Ann Aucote, Chris Goodes, Luke Millar, Lee Yee Cinematographer: Andrew Commis Original Music Score: Gabe Noel Production Designer: Ruby Mathers Lead Actress: Noomi Rapace, Yvonne Strahovski Supporting Actor: Finn Little Supporting Actress: Annika Whiteley Casting Director: Alison Meadows Page 1 of 7 ANIMALS After a decade of partying, Laura and Tyler's friendship is strained when Laura falls in love. -

Acute Misfortune: the Life and Death of Adam Cullen Online

qjbsS [Free read ebook] Acute Misfortune: The Life and Death of Adam Cullen Online [qjbsS.ebook] Acute Misfortune: The Life and Death of Adam Cullen Pdf Free Erik Jensen audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4537247 in Books 2014-09-24Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.50 x .75 x 5.51l, 1.10 #File Name: 186395693X226 pages | File size: 16.Mb Erik Jensen : Acute Misfortune: The Life and Death of Adam Cullen before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Acute Misfortune: The Life and Death of Adam Cullen: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. A harsh realityBy Nathaniel D.A harrowing and tragic tale of Shakespearian proportions. The teetering on the edge of genius and insanity is so visceral in this read and the beauty and destruction that can be produced in the name of creativity is a sad and yet more common combination than we usually want to admit. But it's on full display in this book. A must read for those interested in the biography of artists who also have mental illness.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. ExcellentBy RoseHow have I never heard of this book before? Even though I'm not familiar with Adam Cullen's work, I still really enjoyed this book. Lovers of narrative non fiction will not be disappointed. Thanks Erik.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Crazy... out there. Amazingly written. ...By Joanne OllivierCrazy...out there.Amazingly written.Another one please Erik Jensen. -

Acute Misfortune

ACUTE MISFORTUNE A Film by Thomas M. Wright Based on Acute Misfortune: The Life and Death of Adam Cullen by Erik Jensen “Endurance is more important than truth.” ONE LINE SYNOPSIS The film adaptation of Erik Jensen’s award-winning biography of Adam Cullen is the story of the biographer and his subject, as it descends into a dependent and abusive relationship. OUTLINE The film adaptation of Erik Jensen’s award-winning biography of Adam Cullen is a true story, taking place in Sydney and the Blue Mountains between 2008 to 2012. Erik Jensen was an ambitious nineteen year-old journalist at the Sydney Morning Herald when he was commissioned to write a profile of the painter Adam Cullen, who at forty two was the subject of a career retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. After reading the article, Cullen invited Jensen to write his biography for Thames and Hudson. Acute Misfortune is the story of the biographer and his subject, told inside the years Jensen spent on and off with the painter. It is the story of their increasingly claustrophobic relationship. The Cullen that Jensen met was an iconic figure. His Quotes were reported across the press. But he was also violent and unpredictable. In turn, Jensen was both ruthless and naive - and in Cullen he found a subject he could not hope to understand. He was overwhelmed by him, desperate to know him and trapped by his own hubris. Cullen lied to Jensen. He shot him in the leg with a shotgun. He threw him from a motorbike.