A Prophet (Un Prophète)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Cedric Jimenez

THE STRONGHOLD Directed by Cédric Jimenez INTERNATIONAL MARKETING INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY Alba OHRESSER Margaux AUDOUIN [email protected] [email protected] 1 SYNOPSIS Marseille’s north suburbs hold the record of France’s highest crime rate. Greg, Yass and Antoine’s police brigade faces strong pressure from their bosses to improve their arrest and drug seizure stats. In this high-risk environment, where the law of the jungle reigns, it can often be hard to say who’s the hunter and who’s the prey. When assigned a high-profile operation, the team engages in a mission where moral and professional boundaries are pushed to their breaking point. 2 INTERVIEW WITH CEDRIC JIMENEZ What inspired you to make this film? In 2012, the scandal of the BAC [Anti-Crime Brigade] Nord affair broke out all over the press. It was difficult to escape it, especially for me being from Marseille. I Quickly became interested in it, especially since I know the northern neighbourhoods well having grown up there. There was such a media show that I felt the need to know what had happened. How far had these cops taken the law into their own hands? But for that, it was necessary to have access to the police and to the files. That was obviously impossible. When we decided to work together, me and Hugo [Sélignac], my producer, I always had this affair in mind. It was then that he said to me, “Wait, I know someone in Marseille who could introduce us to the real cops involved.” And that’s what happened. -

Educational Newsletter

Educational Newsletter http://campaign.r20.constantcontact.com/render?llr=zg5n4wcab&v=001K... The content in this preview is based on the last saved version of your email - any changes made to your email that have not been saved will not be shown in this preview. February 2012 Educational Newsletter French Consulate in Boston Our Academic News In This Issue Formation pour professeurs de français Offre de formation "Réaliser une "Voyages en Francophonie" production audiovisuelle" Our 2011 Contest! Nous avons la possibilité de faire SPCD Grant intervenir à Boston un formateur du The Green Connection Centre de liaison de l'enseignement et des médias d'information (CLEMI) sur le CampusArt thème suivant : "Réaliser une production Hewmingway Grant Program audiovisuelle en classe de français langue étrangère" (détails ICI ). Elle La FEMIS pourrait accueillir une trentaine de Merrimack College Language professeurs de middle schools et high schools. La formation se Programs déroulerait sur deux fois 3 heures en "afterschool" les 27 et 28 "Voyages en Francophonie" février, ou le 28 février sur 6 heures en journée (il est possible de n'assister qu'à la première session, mais en faisant l'impasse Printemps des Poètes sur la partie pratique). Tous les frais sont pris en charge par les "A Preview of 2012 in France" services culturels de l'ambassade de France. Si cette formation Clermont-Ferrand International Short intéresse un nombre suffisant d'entre vous, nous serions Film Festival heureux de l'organiser. Dans ce cas, merci de le faire savoir rapidement à Guillaume Prigent compte tenu des délais très Providence French Film Festival courts. -

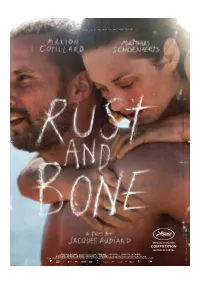

Marion Cotillard Matthias Schoenaerts RUST AND

RustnBone1.indd 1 6/5/12 15:12:51 Why Not Productions and Page 114 present Marion Cotillard Matthias Schoenaerts RUST AND BONE A film by Jacques Audiard Armand Verdure / Céline Sallette / Corinne Masiero Bouli Lanners / Jean-Michel Correia France / Belgium / 2012 / color / 2.40 / 120 min International Press: International Sales: Magali Montet Celluloid Dreams [email protected] 2, rue Turgot - 75009 Paris Tel: +33 6 71 63 36 16 Tel: +33 1 4970 0370 Fax: +33 1 4970 0371 Delphine Mayele [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +33 6 60 89 85 41 Contact in Cannes Celluloid Dreams 84, rue d’Antibes 06400 Cannes Hengameh Panahi +33 6 11 96 57 20 Annick Mahnert +33 6 37 12 81 36 Agathe Mauruc +33 6 82 73 80 04 Director’s Note There is something gripping about Craig Davidson’s short story collection “Rust and Bone”, a depiction of a dodgy, modern world in which individual lives and simple destinies are blown out of all proportion by drama and accident. They offer a vision of the United States as a rational universe in which the physical needs to fight to find its place and to escape what fate has in store for it. Ali and Stephanie, our two characters, do not appear in the short stories, and Craig Davidson’s collection already seems to belong to the prehistory of the project, but the power and brutality of the tale, our desire to use drama, indeed melodrama, to magnify their characters all have their immediate source in those stories. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

February 8Th, 2021

Town Manager’s Newsletter February 8th, 2021 1. Thank You’s - A. Bethany Immigration Services B. National Repertory Orchestra C. Soupz On D. Summit Nordic Ski Club 2. DMMO Download from the BTO - A. COVID Update - February 3rd B. COVID Update - February 5th C. COVID Update - February 8th 3. Summit County Government Meetings - A. Work Session - February 9th B. Special Board of Health Meeting - February 9th C. Regular Meeting - February 9th D. Board of Health Meeting - February 9th & 11th 4. Summit County Government Updates - A. Prescribed Pile Burning at Wildernest-Mesa Cortina Open Space Concluded for the ‘20-‘21 Season B. Creating a Safe Super Bowl LV Experience C. State Releases COVID-19 Dial 2.0 D. Summit County Residents Test Positive for Covid-19 Variants E. Summit County Updates 5 Star Program Guidelines to Align with Dial 2.0 Town Manager’s Newsletter February 8th, 2021 5. Local Organization Updates - A. Breck Film - - February Newsletter - Live Q&A Tonight, February 9th B. Breck Music C. BreckCreate - Upcoming Classes + Events D. Colorado River District Update E. National Repertory Orchestra & Breck Music F. Mountain Top Exploratorium G. Summit Chamber - - Town Hall with Public Health on Wed, Feb. 10th at 10:30am - Child Care, the Workforce & the Economy on Feb. 11th at Noon H. Summit School District - - 2020-2021 Pupil Membership Statistics 6. Colorado Municipal League - A. DOLA to discuss Emergency Rental Assistance through H.R. 133 on Feb. 10 B. Annual Legislative Workshop Deadline to Register is Feb. 10 C. Newsletter - February 8th 7. Colorado Association of Ski Towns - A. Winter 2021 Newsletter Making Summer or Fall Event Plans...Maybe? We want to know your tentative event plans for summer or fall. -

Gender, Sexuality and Ethnicity in Contemporary France

Immigration and Sexual Citizenship: Gender, Sexuality and Ethnicity in Contemporary France Mehammed Amadeus Mack Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mehammed Amadeus Mack All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dissertation Title: “Immigration and Sexual Citizenship: Gender, Sexuality and Ethnicity in Contemporary France” Mehammed Amadeus Mack This dissertation considers discourses bearing on the social dynamics of immigration and postcolonial diversity in contemporary France in light of their interconnections with issues of sexuality and assimilation. Synthesizing and building on recent work by anthropologists, sociologists and cultural theorists it explores the current debate over French identity--a debate that has to a considerable extent revolved around the impact of recent postwar immigration to France and the "integration" of immigrants on the cultural level, and of which a recent symptom has been the Sarkozy government's launch of a public national debate about "l'identité nationale" (national identity). Overall, my project focuses on the intermingling of the cultural and the political in cultural representations of immigrants and their descendants. Specifically, I consider the highly charged terrain of the representation of sexuality. In the discourse on laïcité (secularism) and integration, gender norms and tolerance of homosexuality have emerged as key components and are now often employed to highlight immigrants' "un-French" attitudes. I argue that, as French and immigrant identities have been called into question, sexuality has constituted a favored prism through which to establish the existence of difference. Through the study of cultural representations of immigration, I will explain how the potential of immigrants and their descendants to assimilate is often judged according to the "fitness" of their attitudes about sexuality. -

No Vember/De Cember 20 18

NOV/DEC 2018 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2018 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER Christmas atCINEMASTERS: GFT BILLY WILDER PETERLOO | WIDOWS | NAE PASARAN SUSPIRIA | SHOPLIFTERS | OUTLAW KING FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL | AFRICA IN MOTION THE OLD MAN AND THE GUN | UTØYA | SQIFF GLASGOWFILM.ORG | 0141 332 6535 12 ROSE STREET, GLASGOW, G3 6RB CONTENTS 3 Days in Quiberon 23 Possum + Q&A 21 White Christmas 17 Access Film Club: Blindspotting 28 Science Fair 21 CINEMASTERS: BILLY WILDER Scottish Animation: Access Film Club: Home Alone 28 7 The Apartment 15 Stories Brought to Life Anna and the Apocalypse + short 23 Double Indemnity 15 Shoplifters 22 Archive Film, Propaganda and The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes - 5 15 Spanish Civil War Sorry to Bother You 23 35mm Bad Reputation 20 Super November + Q&A 7 Some Like It Hot 15 Becoming Animal + Q&A 6 Suspiria 22 Sunset Boulevard 15 Been So Long + Q&A 6 Three Identical Strangers 23 COMEDY GENIUS Blue Black Permanent 24 Utøya - July 22 20 9 to 5 25 Blueprint: Scottish Independent Shorts 8 Visible Cinema: It’s A Wonderful Life 28 Shaun of the Dead 25 Calibre + Q&A 5 Visible Cinema: RCS Curates: Widows 28 South Park Sing-a-long - 35mm 25 21 Disobedience 23 Widows DID YOU MISS 22 The Wild Pear Tree 23 Distant Voices, Still Lives Black 47 25 20 Wildlife 22 Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot BlacKkKlansman 25 6 A Woman Captured + Q&A 5 Evelyn + Discussion C’est la vie 25 20 The Workshop 22 An Evening with Beverley Luff Linn Cold War 25 @glasgowfilm 24 Worlds of Ursula K Le Guin 7 The Evil Dead ESTONIA NOW Fahrenheit 11/9 20 AFRICA -

Un Prophète – Synopsis

Release 4 februari 2010 Un Prophète – synopsis Regisseur Jacques Audiard vertelt in Un Prophète het verhaal van de 19-jarige analfabeet Malik El Djebena (Tahar Rahim) die veroordeeld is tot zes jaar gevangenis. De fragiele Malik wordt al snel in het nauw gedreven door de leider van de Corsicaanse maffiabende, die de gevangenis beheerst, en moet een aantal vieze klussen opknappen. Wanneer hij daarin slaagt komt hij iets hoger in de pikorde van de gevangenis, hoewel hij afhankelijk blijft van het goeddunken van de bende. Maar Malik is sluw en maakt in het geheim zijn eigen plannen... Jacques Audiard, een meester in Franse genrefilms zoals Sur mes lèvres (2001) en De battre mon coeur s'est arrêté (2005), won eerder dit jaar met Un Prophète de Grand Prix du Jury op het filmfestival Cannes. De film is een groot box office-succes in Frankrijk en België, wordt wereldwijd enthousiast ontvangen en krijgt lovende kritieken. Na 5 weken trok Un Prophète in Frankrijk al meer dan een miljoen bezoekers. Un Prophète is uitgekozen om Frankrijk te vertegenwoordigen tijdens de 82ste uitreiking van de Academy Awards in de categorie beste buitenlandstalige film. 149 min. / 35mm / Kleur-Couleur / Dolby Digital/ Frans-Corsicaans-Arabisch gesproken Un Prophète – Nederlandse release Un Prophète wordt in Nederland gedistributeerd door ABC/ Cinemien. Beeldmateriaal kan gedownload worden vanaf: www.cinemien.nl/pers of vanaf www.filmdepot.nl Voor meer informatie kunt u zich richten tot Gideon Querido van Frank, +31(0)20-5776010 of [email protected] Un Prophète – cast Malik El Djebena ................................................................................. Tahar Rahim César Luciani ....................................................................................... Niels Arestrup Ryad.................................................................................................... -

Celebrating Forty Years of Films Worth Talking About

2 NOV 18 6 DEC 18 1 | 2 NOV 18 - 6 DEC 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSEcinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT Move over, Braveheart! Last month saw the culmination of our 40th anniversary celebrations here at Filmhouse, and it has been hugely interesting time (for me at any rate!) comparing the us of now with the us of then. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed spending time talking to Filmhouse’s first Artistic Director, Jim Hickey, and finding out in more detail than I knew what myriad ways the business of running Filmhouse has stayed the same and the as many ways it has not (one of these days I’ll write it all down and you can find out how interesting it is for yourselves!). UK film distribution itself has changed immeasurably – the dawn of the multiplex in the latter half of the 1980s saw to that. Back in 1978, Filmhouse itself was part of a sort of movement that saw the birth of a number of similar venues around the UK whose aim was to show a kind of cinema (predominantly foreign language) that simply was not catered for within mainstream film exhibition. Despite 40 years having passed and much having changed, the notion of an audience-driven, ‘curated’ cinema like Filmhouse remains something of a film exhibition anomaly; and something Jim Hickey wrote 30+ years ago rings just as true today as it did then: “But best of all, the new cinemas are being run by those who care about audiences as well as the films that they have paid to watch.” Now, we’ve got a bit of a first for you in November, for we have metaphorically got into bed with Netflix to give one of their films a hugely deserved, exclusive, short run in a cinema – namely David Mackenzie’s splendidly entertaining Robert the Bruce epic, Outlaw King. -

Art Film Theatre Digital Books Food Drink Home Mcr

art home film mcr. theatre org home digital books food drink .FILM may 1 Clouds of Sils Maria, 2014 MAXINE PEAKE AS HAMLET (12A) THE IMMORTAL STORY (15) events Mon 4 May, 18:45 Matinee Sun 10 May, 12:00 Thu 7 May, 18:45 Wed 13 May, 13:30 ROUTES: DANCING TO NEW Sat 9 May, 13:45 See P.04 for details. ORLEANS + SHORTS AND Q&A (PG) From its sell-out run at Manchester’s Royal Classics Sat 2 May, 16:00 Exchange Theatre comes this unique and critically acclaimed production of Shakespeare’s THE FRENCH CONNECTION (18) Dir Alex Reuben/GB 2008/48 mins tragic Hamlet. In this stripped-back, fresh and . Sun 17 May, 12:00 Alex Reuben’s debut feature Routes, is a fast-paced version, BAFTA nominee Maxine road movie through the dance and music of Peake creates a Hamlet for now, giving a Wed 20 May, 13:30 the American Deep South. Inspired by Harry performance hailed as “delicately ferocious” by Our popular ongoing Dir William Friedkin/US 1971/104 mins Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, and The Guardian and “a milestone Hamlet” by the Gene Hackman, Fernando Rey, Roy Scheider evocative of Maya Deren’s seminal Meshes Manchester Evening News. programme brings cinema ‘Popeye’ Doyle (Academy Award-winning Gene Of The Afternoon, Reuben’s film offers an Hamlet is Shakespeare’s most iconic work. The classics to the big screen Hackman) and Buddy Russo (Roy Scheider) idiosyncratic documentation of lesser-known play explodes with big ideas and is the ultimate are tough New York cops attempting to crack forms of American culture, and the extraordinary every month – with each film story of loyalty, love, betrayal, murder and a drug smuggling ring. -

Movie Museum AUGUST 2010 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum AUGUST 2010 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY 65th Anniversary of the Hawaii Premiere! THE GHOST WRITER DOWNFALL Bombing of Hiroshima THE GHOST WRITER HOME (2010-France/Germany/UK) aka Der Untergang BAREFOOT GEN (2010-France/Germany/UK) (2008-Switzerland/France/ in English & in widescreen aka Hadashi no Gen (2004-Germany/Italy/Austria) in English, in widescreen Belgium) (1983-Japan) in German/Russian with in French with English with Ewan McGregor, Pierce in English & in widescreen English subtitles & widescreen with Ewan McGregor, Pierce subtitles & in widescreen Brosnan, Olivia Williams, A powerful animated film on with Bruno Ganz, Alexandra Brosnan, Olivia Williams, with Isabelle Huppert, Olivier Timothy Hutton, Kim the atomic bomb's impact on Maria Lara, Ulrich Matthes, Timothy Hutton, Kim Cattrall, Gourmet, Adelaide Leroux, Cattrall, Tom Wilkinson. the life of a Japanese boy. Corinna Harfouch. Tom Wilkinson, Eli Wallach, Madeleine Budd. Jon Bernthal. Directed by Directed by Directed by Directed and Co-written by Roman Polanski. Mori Masaki. Oliver Hirschbiegel. Directed by Ursula Meier. Roman Polanski. 12:15, 2:30, 4:45, 7:00 & 12:30, 2:00, 3:30, 5:00, 6:30 12:15, 3:00, 5:45 & 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 9:15pm 12:30, 3, 5:30 & 8pm 5 & 8:00pm 6 8:30pm 7 8 & 8:30pm 9 GIOVANNA'S FATHER DOWNFALL V-J Day 65th Anniversary Hawaii Premiere! Hawaii Premiere! aka Il papa di Giovanna aka Der Untergang Hawaii Premiere! RAIN YACOUBIAN BUILDING (2008-Italy) (2004-Germany/Italy/Austria) THE SUN (2008-Bahamas) aka Omaret Yakobean in Italian with English in German/Russian with (2005-Russia/Italy/ in widescreen (2006-Egypt) subtitles & in widescreen English subtitles & widescreen Switzerland/France) in Arabic with English with Silvio Orlando, Francesca with Bruno Ganz, Alexandra in Japanese/English w/ Eng with Renel Brown, Nicki subtitles & in widescreen Neri, Alba Rohrwacher, Ezio Maria Lara, Ulrich Matthes, subtitles & in widescreen Micheaux, CCH Pounder, Ron Adel Imam, Nour El-Sherif, Greggio, Serena Grandi.