10 Florida Field Naturalist Determining the Origin Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reciprocal Admissions Program

ST. PETERSBURG WINTER PARK Florida Holocaust Museum Albin Polasek Museum & Sculpture Garden * (AHS) 727–820–0100 | flholocaustmuseum.org 407–647–6294 | polasek.org | FREE admission 50% off admission NEW YORK Great Explorations Children’s Museum Utica Zoo 727–821–8992 | greatex.org | 50% off admission 315–738–0472 | Uticazoo.org | 50% off admission Sunken Gardens * (AHS) 727–551–3102 | sunkengardens.org | FREE admission PLEASE NOTE TAMPA • Attractions marked with an * indicates free admission. American Victory Ship and Museum 813–228–8766 | americanvictory.org | 50% off admission • Attractions marked (AHS) indicates they are part of the American Horticultural Society Reciprocal Florida Aquarium 813–273–4000 | flaquarium.org | 50% off admission Admission Program. M.O.S.I. (Museum of Science & Industry) • Please contact organization before visiting to confirm (excludes IMAX films) Reciprocal Admission benefits. 813–987–6000 | mosi.org | 50% off admission • Reciprocal Admission benefits are valid only for Tampa Bay History Center member(s) listed on the card, and do not extend to 813–228–0097 | tampabayhistorycenter.org guests. In the case of a family, couple or household 50% off admission card that does not list names, Bok Tower Gardens will Tampa Museum of Art extend the benefit to at least two (2) of the members. 813–274–8130 | tampamuseum.org | 50% off admission University of South Florida Botanical Garden * (AHS) • You must present your Bok Tower Gardens RECIPROCAL 813–974–2329 | gardens.usf.edu | FREE admission membership card and a valid photo ID to receive benefits. ADMISSIONS PROGRAM VERO BEACH JANUARY 1 – DECEMBER 31, 2019 McKee Botanical Garden* (AHS) • Reciprocal admission privileges do not include concerts 772–794–0601 | mckeegarden.org | FREE admission or other special events. -

Front Desk Concierge Book Table of Contents

FRONT DESK CONCIERGE BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS I II III HISTORY MUSEUMS DESTINATION 1.1 Miami Beach 2.1 Bass Museum of Art ENTERTAINMENT 1.2 Founding Fathers 2.2 The Wolfsonian 3.1 Miami Metro Zoo 1.3 The Leslie Hotels 2.3 World Erotic Art Museum (WEAM) 3.2 Miami Children’s Museum 1.4 The Nassau Suite Hotel 2.4 Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) 3.3 Jungle Island 1.5 The Shepley Hotel 2.5 Miami Science Museum 3.4 Rapids Water Park 2.6 Vizcaya Museum & Gardens 3.5 Miami Sea Aquarium 2.7 Frost Art Museum 3.6 Lion Country Safari 2.8 Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) 3.7 Seminole Tribe of Florida 2.9 Lowe Art Museum 3.8 Monkey Jungle 2.10 Flagler Museum 3.9 Venetian Pool 3.10 Everglades Alligator Farm TABLE OF CONTENTS IV V VI VII VIII IX SHOPPING MALLS MOVIE THEATERS PERFORMING CASINO & GAMING SPORTS ACTIVITIES SPORTING EVENTS 4.1 The Shops at Fifth & Alton 5.1 Regal South Beach VENUES 7.1 Magic City Casino 8.1 Tennis 4.2 Lincoln Road Mall 5.2 Miami Beach Cinematheque (Indep.) 7.2 Seminole Hard Rock Casino 8.2 Lap/Swimming Pool 6.1 New World Symphony 9.1 Sunlife Stadium 5.3 O Cinema Miami Beach (Indep.) 7.3 Gulfstream Park Casino 8.3 Basketball 4.3 Bal Harbour Shops 9.2 American Airlines Arena 6.2 The Fillmore Miami Beach 7.4 Hialeah Park Race Track 8.4 Golf 9.3 Marlins Park 6.3 Adrienne Arscht Center 8.5 Biking 9.4 Ice Hockey 6.4 American Airlines Arena 8.6 Rowing 9.5 Crandon Park Tennis Center 6.5 Gusman Center 8.7 Sailing 6.6 Broward Center 8.8 Kayaking 6.7 Hard Rock Live 8.9 Paddleboarding 6.8 BB&T Center 8.10 Snorkeling 8.11 Scuba Diving 8.12 -

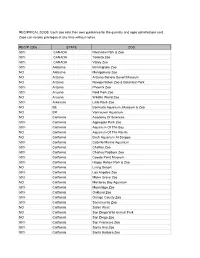

2006 Reciprocal List

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

Florida City Index

41 ALABAMA 137 153 87 167 109 53 27 122 91 84 19 G 122 1 85 2 2 E Bainbridge 29 2 2 O 133 Century 331 71 R 333 84 G 129 97 189 81 84 4 I Valdosta 197 83 A 69 94 Crestview DeFuniak Ponce Chipley 90 7 A 87 Baker Bonifay Marianna L Springs de Leon 26 40 A 90 Holt 90 10 B 333 121 Fernandina Beach A 95A 31 M 79 231 Sneads 267 94 A Milton 10 90 Hillard 1 Yulee 41 85 285 Quincy 27 59 95 319 129 GEORGIA A1A 42 Amelia Island 10 221 A1A 81 Vernon Greensboro 19 53 Jacksonville 87 331 Havana 145 Jennings 41 90A 10 Monticello Museum of 17 85 Niceville 71 90 2 94 International Pensacola 79 69 Madison Science & 301 115 90 90 20 77 12 6 Jasper History (MOSH) Airport Regional Airport Fountain Blountstown ✈ ✈ Navarre 189 Ebro 267 Tallahassee Lee 17 Pensacola 20 90 Grayton Beach Point 20 20 10 White Bryceville A1A 43 Washington 29 90 105 98 98 59 Bristol 20 263 27 Springs 110 Destin 98 Panama City Lamont 295 Atlantic Beach 292 399 51 Fort Walton 441 Jacksonville 9A Shipwreck Gulf 19 Navarre Beach Santa Seaside Bay County Youngstown ✈ 75 Rosa Beach 267 19 41 10 Neptune Beach Island at 21 Breeze Beach International Airport 41 90 18 Adventure Pensacola Sandestin Seagrove Beach 375 53 Live Oak Jacksonville Beach Perdido Beach 231 12 363 59 27 221 90 Landing 71 65 Tallahassee Ponte Vedra Beach Key Blue Mountain Beach Seacrest Beach ALT 251 10 16 202 Ghost Tours of St. -

TEVA 2019-2020 Brochure.Indd

Welcome to your Fun In the Sun Guide to South Florida. Explore all the great places that surround us. From National Parks to State Parks to family attractions to bountiful agri-tourism locations, we are truly blessed to be able to share the place we call home with travelers from around the world. Our Visitor Center is located in Florida City which lies next to the City of Homestead. Both cities are on the upswing with many new hotels and businesses coming into our area. Stroll downtown Homestead’s historic district featuring the Seminole Theatre, Pioneer &Town Hall Museums, and the great Mexican restaurant Casita Tejas. You will get a taste of the diversity of our area from Key West to Miami presented in this visitor guide. We also hope that you will take advantage of our travel app. As our non-profit turns 32 years old, we truly thank our community, the supporting businesses presented in this guide, our Board of Directors and all the women and men who have volunteered at our Visitor Center over these last 32 years. Stop by our Visitor Center. Our staff truly likes to tell people where to go. Mostly, enjoy your trip! Table Of Contents South Florida Featured Attractions 7 - 8 Coral Castle 2 Botanical/Historical 7 - 8 AMR Motorplex 3 Out and About with More RF Orchids 5 Great Attractions 8 - 10 Monkey Jungle 6 Banking 10 Cauley Square 9 Fruit & Vegetable Stands 10 Robert Is Here Fruit Stand 9 Parks & National Parks 13 & 16 Schnebly Redlandʼs Shopping 17 Winery & Brewery 10 Restaurants 17 Flamingo at Everglades Bureaus & Associations 18 National -

FLAMINGO GARDENS Help Us Preserve This Beauty Spot

FLAMINGO GARDENS Help Us Preserve This Beauty Spot 2020 WELCOME TO FLAMINGO GARDENS More than nine decades ago, after the devastating Hurricane of 1926, Davie pioneers, Floyd L. and Jane Wray, planted summer oranges in the rich muck soil of reclaimed Everglades land. This simple act founded one of the earliest tourist attractions and botanical gardens in Florida. With the help of a U.S. Department of Agriculture program, the gardens received foreign plants and trees from around the world in the 20s, 30s, and 40s, establishing an impressive collection of botanical specimens. 2 HELP US Preserve This Beauty Spot From the beginning the Wrays welcomed visitors Our visitor, staff, and technological needs have to their garden. Daily tours of the citrus groves and outgrown the current facilities and infrastructure. the botanical gardens were given to the public, Our facilities no longer meet the needs of the extolling the virtues of citrus, tropical plants, and the 150,000 guests that visit Flamingo Gardens each Everglades. The beauty of the area and the need to year as attendance has surpassed current parking preserve that beauty was paramount to the Wrays. and restroom capacities. The Meeting Room is inadequate to accommodate the requests Through the years Flamingo Gardens has from the community and the ravages brought forth the vision of Mr. & Mrs. of time, storms, and Hurricane Irma Wray, preserving this beautiful and have rendered the space unfit for historical place, protecting native plants public use. and wildlife, and educating the public about the significance of the Everglades. Though facing daunting challenges, You are welcome to Flamingo [Gardens] and are invited to spend as much time as you desire, my only request being.. -

Financial Responsibility Y/N License Code Date

License Date App business business Business Location Location Facility Financial Responsibility Y/N Status Business Name Business Address business City Facility Name Location Address Location City Latitude Longitude Region County Email Classes Code Expires Id State Zip Phone State Zip Phone 32301- 33140- (305)673- N ESA 2/7/12 ISSUED 1590 BGW DESIGNS LIMITED, INC. 1535 W. 27TH. STREET MIAMI BEACH FL 0000 (305)576-8888 WEISS, BARTON G 1535 W. 27TH. STREET, #2 MIAMI BEACH FL 0000 8830 25.71938 -80.42948 FWSB DADE [email protected] I D1, I T1, I D3 32301- 33187- (305)673- N ESA 12/30/11 ISSUED 1591 BGW DESIGNS LIMITED, INC. 1535 W. 27TH. STREET MIAMI BEACH FL 0000 (305)576-8888 WEISS, BARTON G 21200 S.W. 147TH. AVENUE MIAMI FL 0000 8830 25.802558-80.144058FWSB DADE [email protected] I D1, I T1, I D3, II I1 33523- (352)303- N ESA 5/8/12 ISSUED13118 BIDDLE, JESSICA K 38614 CLINTON AVE DADE CITY FL 33525 (352)303-6867 BIDDLE, JESSICA K 36906 CHRISTIAN ROAD DADE CTIY FL 0000 6867 28.4344 -82.205667FWSW PASCO jesscrn11@yahoo,com I A1, I E, II A7, II A9, II B6 90036- 99110- (310)717- OUT OF N ESA 1/26/12 ISSUED 2144 BRIAN STAPLES PRODUCTIONS 910 1/2 S. ORANGE GROVE AVE. LOS ANGELES CA 0000 (310)717-1324 STAPLES, BRIAN 4420 WASHINGTON STREET CLAYTON WA 0000 1324 0 0 OS STATE blstaples@gmail,com I A3, I A6, I A5, II C8 I C2, I E, I B3, I A1, I G1, I H, I A3, I A2, I A6, I A5, I A4, II B6, II Q, II A9, II 33982- 33982- (239)872- A11, II O1, II O5, II A8, II C8, II A15, II N ESA 3/19/12 ISSUED 2688 CARON, LAURI ANN 41660 HORSESHOE ROAD PUNTA GORDA FL 0000 (239)543-1130 CARON, LAURI ANN 41660 HORSESHOE ROAD PUNTA GORDA FL 0000 7952 26.786175-81.766063FWSW CHARLOTTE [email protected] C14, CARVALHOS FRIENDS OF SHINGLE 95682- 33132- (530)903- N ESA 1/29/12 ISSUED 2749 FEATHER P.O. -

Buy 2 Days Get 2 Days Free

The State of Georgia Entertainment Discounts for Employees! Company Code Orlando: 407-393-5862 SOG13 Toll Free: 800-331-6483 March 2020-National *Save Money *Avoid Admission Lines *Have Your TicKets Before You Go *Convenient Delivery Options BUY 2 DAYS GET 2 DAYS FREE ORLANDO & TAMPA ATTRACTIONS Walt Disney World ® Resort – 4 Park Magic Ticket Savings 7D Dark Ride Adventure Orlando – Save 20% Andretti Indoor Karting & Games: Orlando – Save over 35% Universal Orlando – Buy 2 Days, Get 2 Days Free Tampa Bay CityPASS – Save up to 49% Machine Gun America: Orlando – Save over 25% Blue Man Group Orlando – Save up to 25% The Florida Aquarium – Save Over 30% Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition – Save Over 20% Legoland Florida – Save up to 40% Crayola Experience: Orlando – Save Over 35% VIP Shop & Dine 4Less eCard – Save 30% SeaWorld Orlando – Save over 45% Wild Florida Airboats and Gator Park – Safari Park Now Open: Save 30% Victory Casino Cruises – Save Over 55% Aquatica Orlando – Save over 40% Ripley’s Believe It or Not! (Orlando) – Save Over 25% Arcade City Orlando – Save 20% Busch Gardens Tampa Bay – Save up to 45% SEA LIFE Aquarium – Save up to 50% Marineland Dolphin Adventure – Save up to 14% Kennedy Space Center – Save over 30% Chocolate Kingdom – Save Over 45% Orlando Dinner Shows I-Ride Trolley – Save over 45% Revolution Adventures – Save Over 20% Mango’s Tropical Cafe Orlando – Save 55% ZooTampa at Lowry Park – Save up to 25% Machine Gun America: Orlando – Save Over 25% The Outta Control Dinner Show – Save 25% Orlando Starfyer – Save over 30% WonderWorks-Orlando – Save 40% Sleuths Mystery Dinner Show – Save 40% St. -

The Cruise Capital of the World…

Surrounded by the gentle swells of the Atlantic Ocean, Greater Miami and the Beaches is celebrated for its turquoise Welcome to the Cruise waters, white sandy Capital of the World… beaches and picture perfect weather. Myriad attractions, recreational activities, museums, festivals and fairs add a Shan Shan Sheng, Ocean Waves I and II, 2007 Cruise Terminal D, Port of Miami spicy sense of fun. First- Miami-Dade County Public Art Collection class accommodations, world-class cuisine, sizzling nightlife, and infinite shopping opportunities are just part of the magical appeal of our city. Whether it’s your first time here or you’re a returning 701 Brickell Avenue, Suite 2700 visitor, we invite you to Miami, FL 33131 USA 305/539-3000 • 800/933-8448 experience our tropical and MiamiandBeaches.com cosmopolitan destination. MiamiDade.gov/PortOfMiami CruiseMiami.org FSC Logo Here TS 030310 THE CRUISE CAPITAL OF THE WORLD 10 mm high © Greater Miami Convention & Visitors Bureau Tantalizing Treats Attractions Galore Adventures in Shopping A Taste of the Arts Miami’s international flair, seaside locale and fresh, Few places in the world have it all. But Greater Miami and Greater Miami and the Beaches shopping offers everything This town knows how to put on a show. At our performing local produce add up to unforgettable dining experiences. the Beaches definitely does. Miami is an attraction itself. from designer creations to everyday great deals. From elegant arts centers, the playbill includes symphony concerts, New World cuisine tantalizes with dishes featuring Miami is also home to a bevy of unique and historic outdoor malls to hip neighborhood Miami shopping districts, world-class dance, theater and opera, and so much more. -

Free & Cheap Things for Kids to Do in Miami This Summer

Miami on the Cheap Guide Free & Cheap Things for Kids to Do in Miami this Summer Summer vacation is here, and soon your kids may be whining “I’m bored.” We have some suggestions for free and cheap things to do with kids in Miami-Dade this summer. Instead of whining “I’m bored,” your kids will be struggling to choose among all the great options. Summer in South Florida brings free or cheap kids’ movies, the Summer Savings Pass discount for attractions and a chance for kids to bowl free. Plus, we have places like the beach, which are always free, and regular discount days at museums. Here are our suggestions for free and cheap things to do with kids this summer, compiled from Miami on the Cheap. Visit four attractions unlimited times for one price with the Summer Savings Pass The deal is good for Zoo Miami, the Miami Seaquarium, the Museum of Discovery and Science in Fort Lauderdale and Lion Country Safari. It costs $58 plus tax for adults and $48 plus tax for kids ages 3 to 12. If you already hold an annual pass to one of these venues, you can get the Summer Savings Pass at a discount: $33 plus tax for adults and $23 plus tax for youngsters. Details: https://miamionthecheap.com/summer-savings-pass/ Visit five attractions for the price of one with the South Florida Adventure Pass This deal is good for Flamingo Gardens, Sawgrass Recreation Park, XTreme Action Park, Bonnet House Museum and Young at Art Museum. The South Florida Adventure Pass is $45 plus tax for adults and $35 plus tax for children 3-12. -

Inhalt Miami & Key West Miami

Inhalt Bass Museum of Art 32 Biltmore Hotel 33 Miami & Key West Casa Casuarina 34 Coral Castle 34 Vorwort 12 Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden 35 Fantasy Theatre Factory 35 Miami Freedom Tower 37 Gold Coast Railroad Museum 37 Stadtplan Miami 20 History Miami 37 Hofbräu Beerhall 38 Stadtplan Legende 22Holocaust-Memorial 36 Jungle Island 33 Die Geschichte in Kürze 24Lowe Art Museum 39 Matheson Hammock Park 40 Die schönsten Viertel Metro-Dade Cultural Center 40 Miami s 27 Miami Children's Museum 40 Coral Gables 27 Miami Seaquarium 41 Coconut Grove & Umgebung 27Miami Zoo 41 Downtown 28 Monkey Jungle 42 Little Havana 28 Museum of Little Haiti 29 Contemporary Art (MOCA) 42 Wynwood-Streetart-Viertel 29 New World Center 42 Par rot Jungle 43 Sehenswertes 30Perez Art Museum 43 1111 - das weltweit Phillip and Patricia Frost schönste Parkhaus 30 Museum of Science 43 Adrienne Arsht Center Rubell Family Collection 44 for the Performing Arts 30 South Pointe Park 44 American Airline Arena 30 Venetian Pool 45 Ancient Spanish Monastery 31 Villa Vizeaya 46 Bai Harbour 32 World Erotic Art Museum 46 Übernachten 48 dass at the Forge 66 Beacon Hotel South Beach 51 Hoy Como Ayer 66 Bikini Hostel 51 Icon 66 Cardozo Hotel 51 Jazid 66 Catalina Hotel & Beach Club 52 Juvia 67 Circa39 52 UV 68 Clay-Hotel 53 Mansion 68 Clevelander 53 Mangos Tropical Cafe 69 Delano 53 Mynth 70 Dream South Beach 54 Pawn Broker 70 Eden House 54 Set 70 Fontainebleau Miami 54 Tantra 70 Gale South Beach 55 The 1 Rooftop 70 Impala Hotel 56 The Broken Shaker 71 Mondrian South Beach 56 The Fifth 71 Sense Beach House 57 Twist 71 Setai 57 Wall Lounge 71 Shore Club 57 South Beach Hostel 58 Den Promis dicht The Raleigh Hotel 60 auf den Fersen 72 The Standard 60 Essen & Trinken 74 Heiße Nächte und Azul 76 legendäre Clubs 61 B.E.D. -

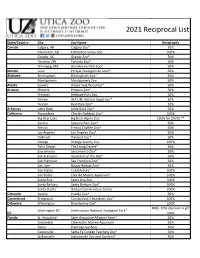

2021 Reciprocal List

2021 Reciprocal List State/Country City Zoo Name Reciprocity Canada Calgary, AB Calgary Zoo* 50% Edmonton, AB Edmonton Valley Zoo 100% Granby, QC Granby Zoo* 50% Toronto, ON Toronto Zoo* 50% Winnipeg, MB Assiniboine Park Zoo* 50% Mexico Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon* 50% Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo* 50% Montgomery Montgomery Zoo 50% Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center* 50% Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo* 50% Prescott Heritage Park Zoo 50% Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium* 50% Tuscon Reid Park Zoo* 50% Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo* 50% California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo* 100% Big Bear Lake Big Bear Alpine Zoo 100% for 2A/3C ** Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo* 50% Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo* 50% Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo* 50% Oakland Oakland Zoo* 50% Orange Orange County Zoo 100% Palm Desert The Living Desert* 50% Sacramento Sacramento Zoo* 50% San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay* 50% San Francisco San Francisco Zoo* 50% San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo* 50% San Mateo CuriOdyssey* 100% San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium* 100% Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo 100% Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo* 100% Santa Clarita Gibbon Conservation Center 100% Colorado Pueblo Pueblo Zoo* 50% Connecticut Bridgeport Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo* 100% Delaware Wilmington Brandywine Zoo* 100% FREE- 10% discount in gift Washington DC Smithsonian National Zoological Park* DC shop Florida St. Augustine Saint Augustine Alligator Farm* 50% Clearwater Clearwater Marine Aquarium 50% Davie Flamingo Gardens 50% Gainesville Santa Fe College Teaching Zoo* 50% Jacksonville Jacksonville