Urban Waterways Newsletter 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEPTEMBER 2017 The

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce SEPTEMBER 2017 the Passenger Count Up at Mobile Airport 20 Years of Industry Growth in Mobile Continues Eagle Awards the business view SEPTEMBER 2017 1 We work for you. With technology, you want a partner, not a vendor. So we built the most accessible, highly responsive teams in our industry. Pair that with solutions o ering the highest levels of reliability and security and you have an ally that never stops working for you. O cial Provider of Telecommunication Solutions to the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce Leading technology. Close to home. business solutions cspire.com/business | [email protected] | 251.459.8999 C SpireTM and C Spire Business SolutionsTM are trademarks owned by Cellular South, Inc. Cellular South, Inc. and its a liates provide products and services under the C SpireTM and C Spire Business SolutionsTM brand. 2 the©2017 business C Spire. All rights view reserved. SEPTEMBER 2017 FOCUS ON WHATFOCUS COUNTS ON Cypress EmploymentWHAT Services Enables COUNTS Employers To Focus On Productivity, Profitability and Staffing Flexibility by Re-Defining Cypress The On-Time, Employment Best-Fit Staffing Services Enables Solution ModelEmployers For Employers To Focus On Productivity, Profitability and Staffing Flexibility by ADMINISTRATIONRe-Defining & CLERKS The On-Time, Best-Fit Staffing Accounting, officeSolution administration, Model sales For personnel, Employers file clerks & legal personnel INDUSTRIALADMINISTRATION & TECHNICAL SKILLS & CLERKS Welders, pipe fitters, riggers, journeyman plumbers -

How the Energy

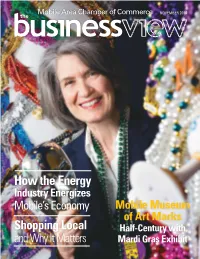

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce NOVEMBER 2014 the How the Energy Industry Energizes Mobile’s Economy Mobile Museum of Art Marks Shopping Local Half-Century with and Why It Matters Mardi Gras Exhibit ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY IS: Fiber optic data that doesn’t slow you down C SPIRE BUSINESS SOLUTIONS CONNECTS YOUR BUSINESS. • Guaranteed speeds up to 100x faster than your current connection. • Synchronous transfer rates for sending and receiving data. • Reliable connections even during major weather events. CLOUD SERVICES Get Advanced Technology Now. Advanced Technology. Personal Service. 1.855.212.7271 | cspirebusiness.com 2 the business view NOVEMBER 2014 the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce NOVEMBER 2014 | In this issue From the Publisher - Bill Sisson ON THE COVER Deborah Velders, director of the Mobile Museum Mobile Takes Bridge Message to D.C. of Art, gets in the spirit of Mardi Gras for the museum’s upcoming 50th anniversary celebration. Story on Recently, the Coastal Alabama as the Chamber’s “Build The I-10 page 10. Photo by Jeff Tesney Partnership (CAP) organized a Bridge Coalition,” as well as the regional coalition of elected officials work of CAP and many others. But from the Mobile Bay region to visit we’re still only at the beginning of Sens. Jeff Sessions and Richard the process. Now that the federal 4 News You Can Use Shelby, Cong. Bradley Byrne, and agencies have released the draft several congressmen from Alabama, Environmental Impact Study, 10 Mobile Museum of Art Celebrates Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi in public hearings have been held and 50 Years Washington, D.C. -

Mobile 1 Cemetery Locale Location Church Affiliation and Remarks

Mobile 1 Cemetery Locale Location Church Affiliation and Remarks Ahavas Chesed Inset - 101 T4S, R1W, Sec 27 adjacent to Jewish Cemetery; approximately 550 graves; Berger, Berman, Berson, Brook, Einstein, Friedman, Frisch, Gernhardt, Golomb, Gotlieb, Gurwitch, Grodsky, Gurwitch, Haiman, Jaet, Kahn, Lederman, Liebeskind, Loeb, Lubel, Maisel, Miller, Mitchell, Olensky, Plotka, Rattner, Redisch, Ripps, Rosner, Schwartz, Sheridan, Weber, Weinstein and Zuckerman are common to this active cemetery (35) All Saints Inset - 180 T4S, R1W, Sec 27 All Saints Episcopal Church; 22 graves; first known interment: Louise Shields Ritter (1971-1972); Bond and Ritter are the only surnames of which there are more than one interment in this active cemetery (35) Allentown 52 - NW T3S, R3W, Sec 29 established 1850, approximately 550 graves; first known interment: Nancy Howell (1837-1849); Allen, Busby, Clark, Croomes, Ernest, Fortner, Hardeman, Howell, Hubbard, Jordan, Lee, Lowery, McClure, McDuffie, Murphree, Pierce, Snow, Tanner, Waltman and Williams are common to this active cemetery (8) (31) (35) Alvarez Inset - 67 T2S, R1W, Sec 33 see Bailey Andrus 151 - NE T2S, R1W, Sec 33 located on Graham Street off Celest Road in Saraland, also known as Saraland or Strange; the graves of Lizzie A. Macklin Andrus (1848-1906), Alicia S. Lathes Andrus (1852-1911) and Pelunia R. Poitevent Andrus (1866-1917), all wives of T. W. Andrus (1846-1925) (14) (35) Axis 34 - NE T1S, R1E, Sec 30 also known as Bluff Cemetery; 12 marked and 9 unmarked graves; first interment in 1905; last known interment: Willie C. Williams (1924-1991); Ames, Ethel, Green, Hickman, Lewis, Rodgers and Williams are found in this neglected cemetery (14) (31) (35) Bailey Inset - 67 T2S, R1W, Sec 33 began as Alvarez Cemetery, also known as Saraland Cemetery; a black cemetery of approximately 325 marked and 85 unmarked graves; first known interment: Emmanuel Alvarez (d. -

What Will It Take to Make Alabama's

TABLE OF CONTENTS BCA Information Building The Best Business Climate 02 A Letter to Alabama Businesses 18 BCA's ProgressPac: Elect, Defend, Defeat, and Recruit 04 2017 Legislative Action Summary 20 Education: A Better Workforce Starts in the Classroom 05 Why Invest in BCA? 22 Infrastructure: Alabama's Arteries of Commerce 06 National Partnerships 24 Manufacturing: Building the State's Economy 07 State Partnerships 26 Labor and Employment: Alabama's Vibrant and Productive 08 BCA 2018 Board of Directors Workforce is No Accident 10 BCA Professional Team 28 Judicial and Legal Reform: Fairness and Efficiency 11 BCA Leadership for all Alabamians 12 Alabama Legislators 29 Environment and Energy: A Healthy Environment is 14 Federal Affairs Good for Business 16 BCA 2018 Events Calendar 30 Health Care: Alabama can Lead the Nation We represent more than 1 million 31 Tax and Fiscal Policy: Fairness and Consistency are Keys to Growth 32 Small Business: The Economic Engine of Alabama working Alabamians and their ability to provide for themselves, their families, and their communities. 1 PERSPECTIVE'18 education and works to serve students and parents. We work to ensure that students receive the appropriate education and skill-training and we look forward to working with the Legislature to accomplish a fair and equitable business environment that includes sound education policies. By working together, Alabama's business community and health care community, including physicians, nurses, hospitals, nursing homes, insurance carriers, and other health care providers and professionals, can inform each other and policy makers about how best to solve the problems facing those who access the health care system and marketplace. -

Alabama African American Historic Sites

Historic Sites in Northern Alabama Alabama Music Hall of Fame ALABAMA'S (256)381-4417 | alamhof.org 617 U.S. Highway 72 West, Tuscumbia 35674 The Alabama Music Hall of Fame honors Alabama’s musical achievers. AFRICAN Memorabilia from the careers of Alabamians like Lionel Richie, Nat King Cole, AMERICAN W. C. Handy and many others. W. C. Handy Birthplace, Museum and Library (256)760-6434 | florenceal.org/Community_Arts HISTORIC 620 West College Street, Florence 35630 W. C. Handy, the “Father of the Blues” wrote beloved songs. This site SITES houses the world’s most complete collection of Handy’s personal instruments, papers and other artifacts. Information courtesy of Jesse Owens Memorial Park and Museum alabama.travel (256)974-3636 | jesseowensmuseum.org alabamamuseums.org. 7019 County Road 203, Danville 35619 The museum depicts Jesse Owens’ athletic and humanitarian achieve- Wikipedia ments through film, interactive exhibits and memorabilia. Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center (256)609-4202 428 West Willow Street, Scottsboro 35768 The Scottsboro Boys trial was the trial pertaining to nine black boys allegedly raping two white women on a train. This site contains many artifacts and documents that substantiate the facts that this trial of the early 1930’s was the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. State Black Archives Research Center and Museum 256-372-5846 | stateblackarchives.net Alabama A&M University, Huntsville 35810 Unique archive museum center which serves as a repository of African Ameri- can history and culture providing a dialogue between present and past through archival collections and exhibits. Weeden House Museum 256-536-7718 | weedenhousemuseum.com 300 Gates Avenue, Huntsville 35801 Ms. -

2017 Spring Commencement

University of South Alabama Alma Mater All hail great university Our Alma Mater dear, South Alabama, red and blue proud colors we revere. Nestled midst the hills of pine enduring throughout time, Upward, onward may your fame continue in its climb. So with thy blessings now send us pray that highest be our aim, University of South Alabama may we ever lif and glorify your name! South Alabama U-S-A! Spring Commencement May 6, 2017 University of South Alabama Spring Commencement Saturday, May 6, 2017 9:30 a.m. Ceremony Bachelor’s Degrees Master’s and Educational Doctoral Degrees Specialist Degrees College of Arts and Sciences College of Arts and Sciences College of Arts and Sciences College of Education College of Education College of Education School of Computing Graduate School College of Medicine School of Continuing Education School of Computing Graduate School and Special Programs School of Computing 2:00 p.m. Ceremony Bachelor’s Degrees Master’s Degrees Doctoral Degrees College of Engineering College of Engineering College of Engineering College of Nursing College of Nursing College of Nursing Mitchell College of Business Mitchell College of Business Mitchell College of Business Pat Capps Covey College of Pat Capps Covey College of Pat Capps Covey College of Allied Health Professions Allied Health Professions Allied Health Professions Processional ..................................................................................................Pomp and Circumstance No. 1 Te USA Commencement Band William H. Petersen, D.M., Conductor Director of Bands and Assistant Professor of Music Presentation of Colors ...............................................................................................Te USA Color Guard Te National Anthem ...................................................................................................Olivia Renee´ Drake Junior Music Major Te USA Commencement Band Invocation .......................................................................................................... -

Known Descendants of Isham Alford (1755-1832) January 2009

Known Descendants of Isham Alford (1755-1832) January 2009 This is a work in progress and is probably not yet complete and it may have some error. The AAFA manager of this branch of the family is descendant, Janice Smith. In an effort to protect the privacy of the living data only five generations is being displayed here. For more information or to report additions and corrections contact Janice with email sent to [email protected]. Be sure to mention Isham or Janice in the subject. 1. Isham Alford #1 b. Oct 30 1755, Franklin County, North Carolina,1 (son of Lodwick Alford #1300 and _____ _____ #1301) ref: ISH755NC,2 m. Est __ 1780, in North Carolina, Anne Ferrell #2, b. May 15 1755, Franklin County, North Carolina, (daughter of John Ferrell #1297 and Ann Fish #1298) d. Bef __ 1820, Georgia. Isham died ___ __ 1832, Troup County, Georgia. There is no proof that Isham was the son of Lodwick Alford however there is some circumstantial evidence suggesting that he might be. The search continues. November 12 1777 Bute Co. NC Deed from Nathan Hall to Isham Alford was proved by oath of Isaac Pippen in Bute Co. Court. [Need source from Lynn] 1778- Isaac, Goodridge, John, Isum Alford took oath of Allegiance to US. (Pencil extract of NC records by William Mitchiner AAFA #0010) [Goodridge son of Lodwick] September 1779 Franklin Co. NC Isham was the Jurat on a transaction selling 455 acres in Franklin County - on the north side of Flat Rock Creek - from Isaac Alford of Franklin County to Thomas Martin of Wake County. -

THE RSA:20 Years on Water Street, NY

Strength. Stability. Security. THE RSA: 20 Years on Water Street, NY The Boards of Control and the Retirement Sys- prior to “Sandy.” There is no debt on the building tems of Alabama (RSA) staff are pleased to present and it is currently 93.3% leased. 55 Water Street is the 37th Annual Report for the fiscal year ended the second largest privately-owned office building September 30, 2013. in America. The RSA currently manages 23 funds with aggre- Renovation continues on the historic Van Ant- gate assets of approximately $35.1 billion. For fiscal werp Building in Mobile, which the RSA purchased year 2013, the Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) as- early in the fiscal year. This building is ten stories sets totaled $20.7 billion, the Employees’ Retirement high and over 58,000 square feet. BBVA Compass System (ERS) assets totaled $10.0 billion, and the Ju- will relocate its Mobile headquarters to the 105-year- dicial Retirement Fund (JRF) assets totaled $255 mil- old building in mid-2014, occupying three floors. The lion. The annualized return was 14.93% for the TRS, Van Antwerp Building is one of Mobile’s oldest struc- 14.60% for the ERS and 14.05% for the JRF. tures and joins RSA’s stable of Port City hold- Market performance during fiscal ings that include the RSA Battle House year 2013 was fairly stable, with Tower, the RSA Trustmark Building, equity markets performing well the Renaissance Mobile River- over the course of the year; do- view Plaza Hotel and The Battle mestic and international equi- House Renaissance Mobile ties returned over 21% during Hotel & Spa. -

July 27, 2020 MOBILE COUNTY COMMISSION the Mobile County

July 27, 2020 MOBILE COUNTY COMMISSION The Mobile County Commission met in regular session in the Government Plaza Auditorium, in the City of Mobile, Alabama, on Monday, July 27, 2020 at 10:00 A. M. The following members of the Commission were present: Jerry L. Carl, President, Merceria Ludgood and Connie Hudson, Members. Also present were Glenn L. Hodge, County Administrator/Clerk of the Commission, Jay Ross, County Attorney, and W. Bryan Kegley II, County Engineer. President Carl chaired the meeting. __________________________________________________ INVOCATION The invocation was given by Commissioner Connie Hudson, Mobile County District 2. __________________________________________________ President Jerry L. Carl: Good morning, Mr. Arthur. We are so excited to see you. Theodore Arthur, Jr., Africatown Direct Descendants, 228 South Williams Avenue, Prichard, AL 36610: I would like to say in the wonderful presence of the almighty God, it is a pleasure to be here. Thank you very much for Commissioner Carl to invite me. Commissioner Ludgood, I have not spoken with you in a while. My main purpose for being here today is to let you know that Pollee Allen was my great-grandfather. He had a daughter named Julia Ellis, who was my grandmother. A lot of people do not know that, so I wanted to make it clear today. We have a lot of people participating on this side of town since the Clotilda was found. When Sylviane A. Diouf came down in 2007, we interviewed with her. Miss Beatrice Ellis was the president at that time and she passed away in 2011. As the vice president, I assumed her role right after that. -

Keeping Seas Safe

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce NOVEMBER 2015 the Mobile Exports Keeping on the Rise Seas Safe Chamber Chase Local Vet Starts Exceeds Goal Global Company WITH YOU ON THE FRONT LINES The battle in every market is unique. Ally yourself to a technology leader that knows a truly e ective solution comes from keeping people at the center of technology. Our dedicated Client Account Executives provide an unmatched level of agility and responsiveness as they work in person to fi ne-tune our powerful arsenal of communication solutions for your specifi c business. Four solutions. One goal. A proven way to get there— Personal service. We’re here to help you win. cspire.com/business | 855.277.4732 | [email protected] 2 the business view NOVEMBER 2015 10623 CSpire CSBS PersonalService 9.25x12.indd 1 6/25/15 1:08 PM the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce NOVEMBER 2015 | In this issue ON THE COVER Jonathan McConnell took his combat experience as a U.S. Marine and turned it into Meridian Consulting, a From the Publisher - Bill Sisson successful worldwide maritime security company. See story on pg. 10. Celebrating 25 Years at VT MAE Photo by L.A. Fotographee. “Some people dream of All you have to do is attend 4 News You Can Use success, while others wake up one of MAE’s employee and work hard at it.” luncheons or family picnics 10 Meridian Consulting – Veteran- I cannot help but recall this to see the impact it has on owned Business has Global quotable quote attributed to an our region. -

Guide to the Municipal Archives (PDF)

INTRODUCTION HISTORY OF MOBILE'S MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT, 1814-1999 Once the capital of the vast French Louisiana Province, and later a strategic military outpost and commercial port for the British and Spanish colonial empires, Mobile became an American possession in 1813. As part of the Mississippi Territory, Mobile was incorporated as a town on January 20, 1814. Town government consisted of a board of seven commissioners, one of whom served as president. When the general assembly of the newly formed State of Alabama met in 1819, one of its first actions was to grant a charter to the City of Mobile. The charter, dated December 17, 1819, provided for the election of a seven member board of aldermen to govern the city. The aldermen elected a mayor from among their ranks until 1826 when the charter was revised to allow for his popular election. In the wake of the city's financial difficulties of 1837-1838, the general assembly amended the charter to provide for a board of common council. The amendment, adopted January 31, 1839, sought to put the city back on sound financial ground by granting the council the authority to approve or disapprove all ordinances and resolutions of the mayor and board of aldermen dealing with financial matters. Large bond issues and mismanagement of municipal funds brought on another financial crisis for the city in the 1870s. As a result, on February 11, 1879, the legislature dissolved the corporation of the City of Mobile and established in its place the Port of Mobile. The executive and legislative functions of the port were vested in a police board. -

A Bibliography of African American Family History

A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF AFRICAN AMERICAN FAMILY HISTORY AT THE NEWBERRY LIBRARY By Jack Simpson and Matt Rutherford 1 Cover Image: Illustration from History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Call # F8349.486 2 A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF AFRICAN AMERICAN FAMILY HISTORY AT THE NEWBERRY LIBRARY by Jack Simpson and Matt Rutherford Chicago: The Newberry Library, ©2005 Free and open to the public, the Newberry Library is an independent humanities library offering exhibits, lectures, classes and concerts relating to its collections. For further information, call our reference desk at (312) 255-3512, visit www.newberry.org, or write the Newberry Library, 60 W. Walton, Chicago, IL. 60610. 3 4 Table of Contents ABOUT THE GUIDE........................................................................................................................................... 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................................. 8 GENERAL SOURCES ......................................................................................................................................... 9 GUIDES AND TOOLS FOR GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH ........................................................................................ 9 GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES FOR AFRICAN AMERICAN GENEALOGY ............................................................. 9 NEWSPAPERS AND PERIODICALS......................................................................................................................