[H]Orrible Muddy English Places’: Downriver, Swandown, and the Mock-Heroic Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iain Sinclair and the Psychogeography of the Split City

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Iain Sinclair and the psychogeography of the split city https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40164/ Version: Full Version Citation: Downing, Henderson (2015) Iain Sinclair and the psychogeog- raphy of the split city. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 IAIN SINCLAIR AND THE PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY OF THE SPLIT CITY Henderson Downing Birkbeck, University of London PhD 2015 2 I, Henderson Downing, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Iain Sinclair’s London is a labyrinthine city split by multiple forces deliriously replicated in the complexity and contradiction of his own hybrid texts. Sinclair played an integral role in the ‘psychogeographical turn’ of the 1990s, imaginatively mapping the secret histories and occulted alignments of urban space in a series of works that drift between the subject of topography and the topic of subjectivity. In the wake of Sinclair’s continued association with the spatial and textual practices from which such speculative theses derive, the trajectory of this variant psychogeography appears to swerve away from the revolutionary impulses of its initial formation within the radical milieu of the Lettrist International and Situationist International in 1950s Paris towards a more literary phenomenon. From this perspective, the return of psychogeography has been equated with a loss of political ambition within fin de millennium literature. -

William Hope Hodgson's Borderlands

William Hope Hodgson’s borderlands: monstrosity, other worlds, and the future at the fin de siècle Emily Ruth Alder A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 © Emily Alder 2009 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter One. Hodgson’s life and career 13 Chapter Two. Hodgson, the Gothic, and the Victorian fin de siècle: literary 43 and cultural contexts Chapter Three. ‘The borderland of some unthought of region’: The House 78 on the Borderland, The Night Land, spiritualism, the occult, and other worlds Chapter Four. Spectre shallops and living shadows: The Ghost Pirates, 113 other states of existence, and legends of the phantom ship Chapter Five. Evolving monsters: conditions of monstrosity in The Night 146 Land and The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’ Chapter Six. Living beyond the end: entropy, evolution, and the death of 191 the sun in The House on the Borderland and The Night Land Chapter Seven. Borderlands of the future: physical and spiritual menace and 224 promise in The Night Land Conclusion 267 Appendices Appendix 1: Hodgson’s early short story publications in the popular press 273 Appendix 2: Selected list of major book editions 279 Appendix 3: Chronology of Hodgson’s life 280 Appendix 4: Suggested map of the Night Land 281 List of works cited 282 © Emily Alder 2009 2 Acknowledgements I sincerely wish to thank Dr Linda Dryden, a constant source of encouragement, knowledge and expertise, for her belief and guidance and for luring me into postgraduate research in the first place. -

Walking, Witnessing, Mapping: an Interview with Iain Sinclair David Cooper and Les Roberts Les Roberts (LR): in Lights out for T

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-space: Manchester Metropolitan University's Research Repository Walking, Witnessing, Mapping: An Interview with Iain Sinclair David Cooper and Les Roberts Les Roberts (LR): In Lights Out for the Territory (2003: 142) you write: ‘We have to recognise the fundamental untrustworthiness of maps: they are always pressure group publications. They represent special pleading on behalf of some quango with a subversive agenda, something to sell. Maps are a futile compromise between information and knowledge. They require a powerful dose of fiction to bring them to life.’ In what ways do maps and mapping practices inform your work as a writer? Iain Sinclair (IS): What I’ve done from the start, I think, has been to try, linguistically, to create maps: my purpose, my point, has always been to create a map of somewhere by which I would know not only myself but a landscape and a place. When I call it a ‘map’, it is a very generalised form of a scrapbook or a cabinet of curiosities that includes written texts and a lot of photographs. I have what could be a map of the world made entirely of these hundreds and hundreds of snapshots that aren’t aesthetically wonderful, necessarily, but are a kind of logging of information, seeing the same things over and over again and creating plural maps that exist in all kinds of times and at the same time. It’s not a sense of a map that wants to sell something or to present a particular agenda of any kind; it’s a series of structures that don’t really take on any other form of description. -

Key Title Information Swandown

Key title information Swandown £20.00 Product Details BESTSELLER – now available again! Swandown is a travelogue and Artist(s) Andrew Kötting, Iain Sinclair odyssey of Olympian ambition; a poetic film-diary about encounter, Publisher Cornerhouse, HOME Artist Film myth and culture. It is also an endurance test and pedal-marathon in ISBN 9780956957139 which Andrew Kötting (the filmmaker) and Iain Sinclair (the writer) Format dual edition DVD PAL & Blu-ray pedal a swan-shaped pedalo from the seaside in Hastings to Hackney Illustrations running time: 94:00 in London, via the English inland waterways. Dimensions 170mm x 135mm With a nod to Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo and a pinch of Dada, Weight 100 Swandown documents Kötting and Sinclair’s epic journey, on which they are joined by invited guests including comedian Stewart Lee, Publication Date: Jan 2015 writer Alan Moore and actor Dudley Sutton. This was a perilous journey, akin to the river voyage of Bogart and Hepburn in The African Queen. It was also, for Kötting, a tribute to the legendary performer, traveller and conceptual artist Bas Jan Ader, who in 1975 was lost at sea attempting to cross the Atlantic in a pocket cruiser. This dual edition DVD and Blu-ray release includes caption subtitles, and 43 minutes of extras including the short films Glitter and Storm by Rebecca E. Marshall, Random Acts and Bunhill Fields, an excerpt from the Filmmakers’ Q&A, and the film trailer. ‘Swandown is utterly funny, deeply lyrical, wholly winning, unchallengeably unique. It converts Kötting at a stroke from an acquired taste to a required one.’ ***** The Financial Times ‘Swandown is a puckish, gently abstract, playfully absurd travelogue.’ **** The Daily Telegraph Swandown was commissioned by the Abandon Normal Devices (AND) Festival and premiered at Cornerhouse, Manchester, 2012. -

Psychogeography in Alan Moore's from Hell

English History as Jack the Ripper Tells It: Psychogeography in Alan Moore’s From Hell Ann Tso (McMaster University, Canada) The Literary London Journal, Volume 15 Number 1 (Spring 2018) Abstract: Psychogeography is a visionary, speculative way of knowing. From Hell (2006), I argue, is a work of psychogeography, whereby Alan Moore re-imagines Jack the Ripper in tandem with nineteenth-century London. Moore here portrays the Ripper as a psychogeographer who thinks and speaks in a mystical fashion: as psychogeographer, Gull the Ripper envisions a divine and as such sacrosanct Englishness, but Moore, assuming the Ripper’s perspective, parodies and so subverts it. In the Ripper’s voice, Moore emphasises that psychogeography is personal rather than universal; Moore needs only to foreground the Ripper’s idiosyncrasies as an individual to disassemble the Grand Narrative of English heritage. Keywords: Alan Moore, From Hell, Jack the Ripper, Psychogeography, Englishness and Heritage ‘Hyper-visual’, ‘hyper-descriptive’—‘graphic’, in a word, the graphic novel is a medium to overwhelm the senses (see Di Liddo 2009: 17). Alan Moore’s From Hell confounds our sense of time, even, in that it conjures up a nineteenth-century London that has the cultural ambience of the eighteenth century. The author in question is wont to include ‘visual quotations’ (Di Liddo 2009: 450) of eighteenth- century cultural artifacts such as William Hogarth’s The Reward of Cruelty (see From Hell, Chapter Nine). His anti-hero, Jack the Ripper, is also one to flaunt his erudition in matters of the long eighteenth century, from its literati—William Blake, Alexander Pope, and Daniel Defoe—to its architectural ideal, which the works of Nicholas Hawksmoor supposedly exemplify. -

The Alien in Greenwich. Iain Sinclair & the Millennium Dome

The Alien in Greenwich. Iain Sinclair & the Millennium Dome by Nicoletta Vallorani THE DOME THAT FELL ON EARTH For Iain Sinclair, London is a life project. It tends to take the same ideal shape of the city he tries to tell us about: a provisional landscape (Sinclair 2002: 44), multilevel and dynamically unstable, invaded by memories, projects, plans and virtual imaginations, walked through and re-moulded by the walker, finally fading away at its endlessly redrawn margins. One gets lost, and in doing so, he learns something more about the place he inhabits1: I’m in mid-stride, mid-monologue, when a deranged man (French) grabs me by the sleeve […] There’s something wrong with the landscape. Nothing fits. His compass has gone haywire. ‘Is this London?’ he demands, very politely. Up close, he’s excited rather than mad. Not a runaway. It’s just that he’s been working a route through undifferentiated suburbs for hours, without reward. None of the landmarks – Tower Bridge, the Tower of London, Harrod’s, the Virgin Megastore – that would confirm, or justify, his sense of the metropolis. But his question is a brute. ‘Is this London?’ Not in my book. London is whatever can be reached in a one-hour walk. The rest is fictional. […] ‘Four miles’ I reply. At a venture. ‘London.’ A reckless improvisation. ‘Straight on. Keep going. Find a bridge and cross it.’ I talk as if translating myself into a language primer (Sinclair & Atkins 1999: 38-43). Here, though conjured up by specific landmarks (Tower Bridge, the Tower of London, Harrod’s, the Virgin Megastore) and a few permanent inscriptions (the river and its bridges), the space of London stands out as a fiction made true by the steps of the walker. -

Iain Sinclair's Olympics

Iain Sinclair’s Olympics volume 34 number 16 30 august 2012 £3.50 us & canada $4.95 David Trotter: Lady Chatterley’s Sneakers Karl Miller: Stephen Spender’s Stories Stefan Collini: Eliot and the Dons Bruce Whitehouse: Mali Breaks Down Sheila Heti: ‘Leaving the Atocha Station’ London Review of Books volume 34 number 16 30 august 2012 £3.50 us and canada $4.95 3 David Trotter Lady Chatterley’s Sneakers editor: Mary-Kay Wilmers deputy editor: Jean McNicol senior editors: Christian Lorentzen, 4 Letters Karuna Mantena, Rosinka Chaudhuri, Amit Pandya, Ananya Vajpeyi, Paul Myerscough, Daniel Soar assistant editors: Andrew Whitehead, Miles Larmer, Marina Warner, A.E.J. Fitchett, Joanna Biggs, Deborah Friedell Stan Persky editorial assistant: Nick Richardson editorial intern: Alice Spawls contributing editors: Jenny Diski, 8 Steven Shapin World in the Balance: The Historic Quest for an Absolute System of Measurement Jeremy Harding, Rosemary Hill, Thomas Jones, by Robert Crease John Lanchester, James Meek, Andrew O’Hagan, Adam Shatz, Christopher Tayler, Colm Tóibín consulting editor: John Sturrock 11 Karl Miller New Selected Journals, 1939-95 by Stephen Spender, edited by Lara Feigel and publisher: Nicholas Spice John Sutherland associate publishers: Margot Broderick, Helen Jeffrey advertising director: Tim Johnson 12 Bill Manhire Poems: ‘Old Man Puzzled by His New Pyjamas’, ‘The Question Poem’ advertising executive: Siddhartha Lokanandi advertising manager: Kate Parkinson classifieds executive: Natasha Chahal 13 Stefan Collini The Letters of T.S. -

Iain Sinclair

Iain Sinclair: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Sinclair, Iain, 1943- Title: Iain Sinclair Papers Dates: 1882-2009 (bulk 1960s-2008) Extent: 135 document boxes, 8 oversize boxes (osb) (56.7 linear feet), 23 oversize folders (osf), 15 computer disks Abstract: The papers of British writer Iain Sinclair consist of drafts of works, research material, juvenilia, notebooks, personal and professional correspondence, business files, financial files, works by others, ephemera, and electronic files. They document Sinclair’s prolific and diverse career, from running his own press to his wide range of creative output including works of poetry, fiction, non-fiction, edited anthologies, screenplays, articles, essays, reviews, and radio and television contributions. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4930 Language: English; some French, German, and Italian Access: Open for research. Researchers must register and agree to copyright and privacy laws before using archival materials. Some materials restricted due to condition and conservation status. Use Policies: Ransom Center collections may contain material with sensitive or confidential information that is protected under federal or state right to privacy laws and regulations. Researchers are advised that the disclosure of certain information pertaining to identifiable living individuals represented in the collections without the consent of those individuals may have legal ramifications (e.g., a cause of action under common law for invasion of privacy may arise if facts concerning an individual's private life are published that would be deemed highly offensive to a reasonable person) for which the Ransom Center and The University of Texas at Austin assume no responsibility. -

In Conversation with Iain Sinclair

In Conversation with Iain Sinclair (1 February 2018) by Anna Viola Sborgi and Lawrence Napper IAIN SINCLAIR has been narrating London’s life since the mid-Seventies. He has captured the city in a series of successful novels – White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings (1987), Downriver (1991) – and non-fiction books – London Orbital (2002), Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire: A Confidential Report (2009), Ghost Milk (2011), and London Overground: A Day’s Walk around the Ginger Line (2015). He was trained as a filmmaker; his work is rich with interdisciplinary connections and he has collaborated with other artists both on their independent projects and on films inspired by his own work, such as, respectively, Memo Mori (Emily Richardson, 2009), Swandown (with Andrew Kötting, 2012) and London Orbital (with Chris Petit, 2002). In 2017, Sinclair published The Last London, an elegy to the impending disappearance of the city, and this – he claims – is also going to be his last London book. Our journal issue examines London’s cosmopolitanism at a time of crisis, so we set out to ask him about its origins and about whether this will really be his ‘last word on London’.1 1 Sinclair’s new book, Living with Buildings: Walking with Ghosts – On Health and Architecture, has just come out in September 2018, and, to the relief of his affectionate readers, London is still there, though among other locations this time. Interviste/Entrevistas/Entretiens/Interviews N. 19 – 05/2018 171 Sinclair has famously made his home in East London, so, on our way to the interview, we met on a cold day in February in the little green by Haggerston station, overlooked by All Saints Church. -

Lee Harwood Obituary. Final Version the INDEPENDENT

Biographer to the poet John Clare, Iain Sinclair was minded of Lee Harwood, 'full-lipped, fine-featured : clear eyes set on a horizon we can't bring into focus. Harwood's work, from whatever era, is youthful and optimistic: open.' Poet. Worker. British Rail guard, Better Books manager, forester, museum attendant, stone mason, exam invigilator, theatre dresser, bus conductor, postal clerk (a GPO letter framed in his bathroom commends Harwood's courage diffusing an armed raid at Western Road Post Office, Hove). Jobs that may appear modest entailed craft and motion, and a circular motion which matched his way of walking in the world with tenderness, and locally up onto the South Downs to see a rare orchid. Lee Harwood was raised during wartime near Weybridge in Chertsey. As a child his bedroom window was blown in by a German bomb exploding nearby. His poetry typified his life. Ascetic, delicate, gentle and candid : attentive and careful. He read English at Queen Mary College, London. Raising a young son Blake with Jenny Goodgame Harwood wrote 'Cable Street', a prose poem of place : Stepney with anti-Fascist testimony. His eye for Surrealism led him, at 24, to seek the Dada poet Tristan Tzara in Paris in 1963. He gained Tzara's blessing for his translations : a commitment which spanned 25 years of publications. The American poet John Ashberry had already lived in Paris for ten years when he met Harwood in 1965. The impact on Harwood's poetry on meeting Ashberry was immediate. Their relationship triggered a lifelong friendship. By 1967 he'd settled in Brighton, then in Hove. -

Contemporary British Literature and Urban Space After Thatcher

STATION TO STATION: CONTEMPORARY BRITISH LITERATURE AND URBAN SPACE AFTER THATCHER by KIMBERLY DUFF BA (Hons.), Simon Fraser University, 2001 MA, Simon Fraser University, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2012 © Kimberly Duff, 2012 ABSTRACT “Station to Station: Contemporary British Literature and Urban Space After Thatcher,” examines specific literary representations of public and private urban spaces in late 20th and early 21st-century Great Britain in the context of the shifting tensions that arose from the Thatcherite shift away from state-supported industry toward private ownership, from the welfare state to an American-style free market economy. This project examines literary representations of public and private urban spaces through the following research question: how did the textual mapping of geographical and cultural spaces under Margaret Thatcher uncover the transforming connections of specific British subjects to public/private urban space, national identity, and emergent forms of historical identities and citizenship? And how were the effects of such radical changes represented in post-Thatcher British literary texts that looked back to the British city under Thatcherism? Through an analysis of Thatcher’s progression towards policies of privatization and social reform, this dissertation addresses the Thatcherite “cityspace” (Soja) and what Stuart Hall -

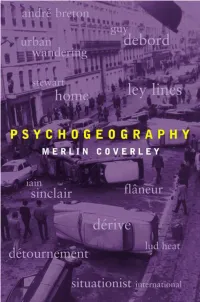

2D3bc7b445de88d93e24c0bab4

PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 2 Other titles in this series by the same author: London Writing PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 3 Psychogeography MERLIN COVERLEY POCKET ESSENTIALS PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 4 First published in 2006 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts,AL5 1XJ www.pocketessentials.com © Merlin Coverley 2006 The right of Merlin Coverley to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publishers. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 904048 61 7 EAN 978 1 904048 61 9 24681097531 Typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPD Ltd, Ebbw Vale,Wales PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 5 To C at h e r i n e PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 6 PSYCHOGEOPE 4/5/06 1:52 pm Page 7 Contents Introduction 9 1: London and the Visionary Tradition 31 Daniel Defoe and the Re-Imagining of London; William Blake and the Visionary Tradition; Thomas De Quincey and the Origins of the Urban Wanderer; Robert Louis Stevenson and the Urban Gothic; Arthur Machen and the Art of Wandering;