8. Durántez & Martínez ENG VF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anuario 2019

RESEARCH TEAM FOR SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTION IN CANTABRIA 2019 ACTIVITY SOSPROCAN TEAM SOSPROCAN TEAM The hosts more than 60 SOSPROCAN team DEPRO Research Group researchers of the University of Cantabria with • Head of the Group: background in the analysis, design and • Prof. Ángel Irabien Gulías optimization of environmental and production ASP Research Group processes. • Head of the Group: • Prof. Inmaculada Ortiz Uribe The aim of this team is to develop cutting-edge TAB Research Group research to progress the sustainability and • Head of the Group: innovation of production, energy and • Prof. Ane Urtiaga Mendía environmental processes. IPS Research Group The members of SOSPROCAN team belong to • Head of the Group • Prof. Raquel Ibáñez Mendizábal four research groups: New Head of the Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering Department Prof. Ane Urtiaga was nominated as Head of the Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering Department. The event, chaired by the Rector of the University of Cantabria, Prof. Ángel Pazos, took place on October 16th, 2019. A representative group of researchers of the Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Department wanted to share with her this moment. Prof. Angel Irabien Prof. Inmaculada Ortiz Prof. Ane M. Urtiaga Prof. Raquel Ibáñez Head of the research group Head of the research group Head of the research group Head of the research group DEPRO PAS TAB IPS [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Aurora Garea Prof. Daniel Gorri Ignacio Fernández [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] -

Infotainment Programs As Substitutes for Leaders' Debates

RLCS, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 76, 59-80 [Research] DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2020-1437 | ISSN 1138-5820 | Year 2020 Infotainment programs as substitutes for leaders’ debates: the case of Miguel Ángel Revilla Los programas de infoentretenimiento como sustituto de los debates electorales: el caso de Miguel Ángel Revilla Noelia Fontecoba. University of Vigo. Spain. [email protected] [CV] Ana Belén Fernández-Souto University of Vigo. Spain [email protected] [CV] Iván Puentes-Rivera University of A Coruña. Spain. [email protected] [CV] This article is part of the studies carried out within the research projects framework “DEBATv”, Leaders’ Debates on Spanish television: Models, Process, Diagnose and Suggestion” (CSO2017-83159-R), project of R+D+I (challenges) financed by Ministerio de Innovación, Ciencia y Universidades and Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) of the Spanish Government, with the support of European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) of the European Union (EU). How to cite this article / Standard reference Fontecoba, N., Fernández-Souto, A. & Puentes-Rivera, I. (2020). Infotainment programs as substitutes for leaders’ debates: the case of Miguel Ángel Revilla. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (76), 59-80. https://www.doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1437 ABSTRACT Currently, the role of political leaders has acquired a new dimension. Television and social media have made, through image, the attention be focused on the candidate and not on ideas or programs. Thus, the leader is not just as such for his/her intellectual qualities, but also for his/her media competence. With this new picture, where more iconic and show centered politics take place, television has incorporated the presence of politicians in their infotainment programs with aims of drawing the highest number of audience possible. -

APROMAR Report AQUACULTURE in SPAIN 2020 0.Pdf

Index 1. Executive Summary 3 2. Introduction 5 3. Aquaculture in the world 8 3.1. Global availability of aquatic products 8 3.2. Situation of aquaculture in the world 10 3.3. Aquaculture productions in the world 11 3.4. Aquaculture productions by groups and by environments 16 3.5. Potential of aquaculture and sustainable development 18 4. Aquaculture in the European Union 20 4.1. Situation of aquaculture in the European Union 20 4.2. Situation of finfish aquaculture in the European Union 24 4.3. Situation of shellfish aquaculture in the European Union 27 4.4. Potential of European aquaculture 28 4.5. Videos of interest 30 5. Aquaculture production in Spain and Europe 31 5.1. Aquatic food production in Spain 31 5.2. Types of aquaculture facilities in Spain 34 5.3. Number of aquaculture establishments in Spain 35 5.4. Employment in aquaculture in Spain 36 5.5. Consumption of aquaculture feed in Spain 37 5.6. Marine aquaculture in Spain and Europe 38 5.7. Freshwater aquaculture in Spain and Europe 63 6. Marketing and consumption of aquaculture products in Europe and Spain 68 6.1. Consumption of aquatic products in the European Union 68 6.2. Food consumption in Spain 70 6.3. Consumption of aquatic products in Spain 70 6.4. Consumption of fresh aquatic products in Spain 73 6.5. Sea bream market development 75 6.6. Sea bass market development 78 6.7. Turbot market development 80 7. Spanish scientific production in the field of aquaculture 82 8. The challenges of aquaculture in Spain 89 9. -

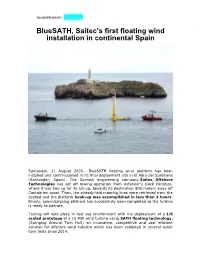

PR Bluesath Installation

BlueSATH, Saitec’s first floating wind installation in continental Spain Santander, 11 August 2020.- BlueSATH floating wind platform has been installed and commissioned in its final deployment site in El Abra del Sardinero (Santander, Spain). The Spanish engineering company Saitec Offshore Technologies has set off towing operation from Astander’s Dock Pontejos, where it was tied up for its set-up, towards its destination 800 meters away off Cantabrian coast. Then, the already-laid mooring lines were retrieved from the seabed and the platform hook-up was accomplished in less than 3 hours. Finally, commissioning offshore has successfully been completed so the turbine is ready to operate. Testing will take place in real sea environment with the deployment of a 1:6 scaled prototype of a 10 MW wind turbine using SATH floating technology, (Swinging Around Twin Hull) an innovative, competitive and cost efficient solution for offshore wind industry which has been validated in several water tank tests since 2014. The location in El Abra del Sardinero has been chosen due to its ideal characteristics to carry out the tests as it offers scaled conditions that perfectly adapted to BlueSATH platform. David Carrascosa, CTO Saitec Offshore Technologies, has commented that this is "the definitive step to test the technology in real conditions". He has also affirmed that this kind of energy has a very high local content, so it is a lever to generate employment. In addition, he has remarked that this is an emerging market that has huge possibilities by removing the depth barriers. And he concluded by saying that "we are facing a very good opportunity for Spain to once again be a pioneer in renewables". -

Responsable General: José Miguel López Higuera

Responsable General: José Miguel López Higuera Índice/Outlook I.‐ Resumen/Summary 4 II.‐ Datos Significativos/Significant Data 6 III.‐ Conferencias Invitadas/Invited Talks 7 IV.‐ Premio s Optoel´11/Optoel´11 Awards 8 V.‐ Exhibición/Exhibition 11 VI.‐ Reportaje Gráfico/Graphic Report 13 VII.‐ Reportaje Gráfico Específico 28 José Miguel López-Higuera e-mail: [email protected] Responsable General Optoel´11 Web: http://grupos.unican.es/GIf Informe Final/Final Report Contiene un breve resumen, datos y detalles de lo más significativo acontecido en la reunión. Se finaliza con un reportaje gráfico que ilustra lo anterior. It contains a brief report on what has taken place in the meeting: data and details on the most relevant issues are also considered. A graphic coverage illustrating the above mentioned points will also be included at the end. I. Resumen Auspiciado por el Comité de Optoelectrónica de la Sociedad Española de Óptica (SEDÓPTICA) Optoel es un foro en el que se comunican, discuten e intercambian los últimos avances científicos y técnicos en el campo de la Fotónica. Bienalmente se ha venido celebrando en regiones de influencia en el sector y tras iniciarse la serie en Aragón y circular por Barcelona, Madrid, Elche, Bilbao y Málaga, la última edición, OPTOEL 2011, se celebró en Santander entre el 29 de junio y el 1 de julio de 2011. Fue inaugurada por el presidente de Cantabria, Ignacio Diego, y el Presidente de la CRUE y rector de la Universidad de Cantabria Federico Gutiérrez Solana. Se constituyó un excelente foro en el que se debatieron y discutieron los avances realizados y las nuevas tendencias; se fomentó la colaboración y cohesión de los distintos agentes; se aportó visibilidad internacional a la industria y grupos de investigación presentes y, se incentivó la participación e interacción de los investigadores jóvenes llamados a ser actores principales en la I+D+i española en la materia en los cruciales años venideros. -

Santander Encounter of Music and Academy

Cantabria and the city of Santander host the Santander Encounter of Music and Academy, and offer their best scenarios at the service of this wonderful educational and musical project, a one-of-a-kind international event in the world years SantanDER ENCOUNTER OF MUSIC AND ACADEMY CANTABRIA 2001—2021 Paloma o’Shea Founding President of the Albéniz Foundation he Santander Music and Academy Encounter was born alongside the beginning of this century. I had visited Tanglewood Music School in Massachusetts, led by Leon Fleisher, and saw that the concepts of a Tsummer music festival and an academy merged there with a level of perfection that was difficult to achieve in Europe. At the same time, there was an increasingly evident gap in the music season in Santander and the entire region. With these two realities in mind, the Albéniz Foundation designed the Encounter of Music and Academy, and offered it to the Government of Cantabria. Their response was immediate and positive and, since then, both entities promote the project side by side each year. For its part, the Santander City Council enthusiastically joined the initiative. In addition, the Menéndez Pelayo International University, the University of Cantabria, and many private companies in the region decided to collaborate on a project that, from the onset, enjoyed the public’s favor. During these years, the Encounter has hosted top international academic experts and performers of each instrument. Their names are included in this book, but I would like to remember here one who was the soul of the Encounter every time he came: our dear Professor Dmitri Bashkirov, who has just left us. -

The Case of Miguel Ángel Revilla

RLCS, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 76, 59-80 [Research] DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2020-1437 | ISSN 1138-5820 | Year 2020 Infotainment programs as substitutes for leaders’ debates: the case of Miguel Ángel Revilla Los programas de infoentretenimiento como sustituto de los debates electorales: el caso de Miguel Ángel Revilla Noelia Fontecoba. University of Vigo. Spain. [email protected] [CV] Ana Belén Fernández-Souto University of Vigo. Spain [email protected] [CV] Iván Puentes-Rivera University of A Coruña. Spain. [email protected] [CV] This article is part of the studies carried out within the research projects framework “DEBATv”, Leaders’ Debates on Spanish television: Models, Process, Diagnose and Suggestion” (CSO2017-83159-R), project of R+D+I (challenges) financed by Ministerio de Innovación, Ciencia y Universidades and Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) of the Spanish Government, with the support of European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) of the European Union (EU). How to cite this article / Standard reference Fontecoba, N., Fernández-Souto, A. & Puentes-Rivera, I. (2020). Infotainment programs as substitutes for leaders’ debates: the case of Miguel Ángel Revilla. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (76), 59-80. https://www.doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1437 ABSTRACT Currently, the role of political leaders has acquired a new dimension. Television and social media have made, through image, the attention be focused on the candidate and not on ideas or programs. Thus, the leader is not just as such for his/her intellectual qualities, but also for his/her media competence. With this new picture, where more iconic and show centered politics take place, television has incorporated the presence of politicians in their infotainment programs with aims of drawing the highest number of audience possible. -

A N N U a L R E P O R T 2 0

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Index 3 Presentation 5 Board of Trustees 6 Advisory Councils 7 Management Team 8 Summary of Activities in 2014 9 Investment in 2014 10 Chairman’s Letter 13 Emilio Botín - Chairman (1993-2014) Activities in 2014 30 Botín Centre 32 Science 34 Trend Observatory 36 Education 38 Rural Development 40 Social Action 42 Collaborations 2 | EMILIO BOTÍN - CHAIRMAN (1993-2014) Presentation Fundación Marcelino Botín was created in 1964 by Marcelino Botín Sanz de Sautuola and his wife, Carmen Yllera, to promote social development in Cantabria. Today, fifty years later, having kept its main focus on Cantabria, the Fundación Botín operates all over Spain and Latin America, contributing to the overall development of society by exploring new ways of uncovering creative talent and supporting it to generate cultural, social and economic wealth. Fundación Botín organises programmes in the realms of the arts and culture, education, science and rural development, and supports social institutions in Cantabria so as to reach those most in need. It has also created a Trend Observatory to gain in-depth knowl- edge of society and pinpoint key factors to help generate wealth and guide development. The Observatory also promotes talent detection and development programmes in the so- cial and public sectors. The Foundation’s headquarters are in Santander, where it has an exhibition hall as well as El Promontorio and Villa Iris, two emblematic locations in the city used for institutional events and for holding exhibitions and workshops, respectively. Since 2012 it has had offices in Madrid to cater for the growing demands of its activity. -

Fifth REHABEND Congress)

REHABEND 2014 CONSTRUCTION PATHOLOGY, REHABILITATION TECHNOLOGY AND HERITAGE MANAGEMENT (Fifth REHABEND Congress) Santander (Spain), April 1-4, 2014 UNIVERSITY OF CANTABRIA Civil Engineering School Department of Structural and Mechanical Engineering Building Technology R&D Group (GTED-UC) Avenue Los Castros s/n 39005 SANTANDER (SPAIN) Tel: +34 942 201 738 (43) Fax: +34 942 201 747 E-mail: [email protected] www.rehabend2014.unican.es FIFTH LATIN AMERICAN CONGRESS ON CONSTRUCTION PATHOLOGY, REHABILITATION TECHNOLOGY AND HERITAGE MANAGEMENT REHABEND 2014 ORGANIZED BY: UNIVERSITY OF CANTABRIA TECHNOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF CONSTRUCTION TECNALIA BUILDING TECHNOLOGY R&D GROUP VALÈNCIA PARC TECNOLÒGIC PARQUE TECNOLÓGICO DE BIZKAIA E.T.S. ING. DE CAMINOS, C. Y P. AVDA. LOS AVDA. BENJAMÍN FRANKLIN 17 C/ GELDO, EDIFICIO 700 CASTROS S/N, 39005 SANTANDER 46980 PATERNA, VALENCIA 48160 DERIO www.gted.unican.es www.aidicio.es www.tecnalia.com CONFERENCE CHAIRMEN: LUIS VILLEGAS JAVIER YUSTE JESÚS DÍEZ CONGRESS COORDINATORS: IGNACIO LOMBILLO CLARA LIAÑO HAYDEE BLANCO EDITORS: LUIS VILLEGAS IGNACIO LOMBILLO HAYDEE BLANCO YOSBEL BOFFILL INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE: HUMBERTO VARUM – UNIVERSITY OF AVEIRO (PORTUGAL) PERE ROCA – TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF CATALONIA (SPAIN) ANTONIO NANNI – UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI (USA) The editors does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or quality of the information provided by any article published. The information and opinion contained in the publications of are solely those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editors. Therefore, we exclude any claims against the author for the damage caused by use of any kind of the information provided herein, whether incorrect or incomplete. -

37º IAHS World Congress on Housing

REHABEND 2014 CONSTRUCTION PATHOLOGY, REHABILITATION TECHNOLOGY AND HERITAGE MANAGEMENT (Fifth REHABEND Congress) Santander (Spain), April 1-4, 2014 UNIVERSITY OF CANTABRIA Civil Engineering School Department of Structural and Mechanical Engineering Building Technology R&D Group (GTED-UC) Avenue Los Castros s/n 39005 SANTANDER (SPAIN) Tel: +34 942 201 738 (43) Fax: +34 942 201 747 E-mail: [email protected] www.rehabend2014.unican.es FIFTH LATIN AMERICAN CONGRESS ON CONSTRUCTION PATHOLOGY, REHABILITATION TECHNOLOGY AND HERITAGE MANAGEMENT REHABEND 2014 ORGANIZED BY: UNIVERSITY OF CANTABRIA TECHNOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF CONSTRUCTION TECNALIA BUILDING TECHNOLOGY R&D GROUP VALÈNCIA PARC TECNOLÒGIC PARQUE TECNOLÓGICO DE BIZKAIA E.T.S. ING. DE CAMINOS, C. Y P. AVDA. LOS AVDA. BENJAMÍN FRANKLIN 17 C/ GELDO, EDIFICIO 700 CASTROS S/N, 39005 SANTANDER 46980 PATERNA, VALENCIA 48160 DERIO www.gted.unican.es www.aidicio.es www.tecnalia.com CONFERENCE CHAIRMEN: LUIS VILLEGAS JAVIER YUSTE JESÚS DÍEZ CONGRESS COORDINATORS: IGNACIO LOMBILLO CLARA LIAÑO HAYDEE BLANCO EDITORS: LUIS VILLEGAS IGNACIO LOMBILLO HAYDEE BLANCO YOSBEL BOFFILL INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE: HUMBERTO VARUM – UNIVERSITY OF AVEIRO (PORTUGAL) PERE ROCA – TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF CATALONIA (SPAIN) ANTONIO NANNI – UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI (USA) The editors does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or quality of the information provided by any article published. The information and opinion contained in the publications of are solely those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editors. Therefore, we exclude any claims against the author for the damage caused by use of any kind of the information provided herein, whether incorrect or incomplete. -

II Edición GYLF 2017 Introducción

II Edición GYLF 2017 Introducción La Segunda Edición del Global Youth Leadership Forum se celebrará del 24 al 30 de septiembre de 2017 en el Palacio de la Magdalena de Santander (España). Impulsado por Naciones Unidas (a través de la Oficina de Naciones Unidas Contra la Droga y el Delito), el Banco Mundial y los Gobiernos de España, Santander y Cantabria, numerosos gobiernos, organismos internacionales, empresas y universidades de primer nivel se han sumado en la promoción del primer foro mundial de debate intergeneracional para el análisis de los principales retos que afrontará la Comunidad Internacional en los próximos años. A lo largo de siete días, 200 jóvenes líderes (menores de 40 años) con importantes responsabilidades en sus países, convivirán y debatirán con las principales figuras mundiales del ámbito político, económico, social y académico sobre los desafíos que, como sociedad, afrontaremos en los próximos años. Por ello, y convencidos de la enorme potencialidad que tiene este nuevo escenario para la mejora de las condiciones de vida de nuestros conciudadanos, hemos creado el Global Youth Leadership Forum (GYLF), espacio que pretende convertirse en centro de debate y discusión entre los principales actores internacionales (Gobiernos, Organismos Internacionales, Empresas, Universidades…) y jóvenes líderes que ya ostentan importantes responsabilidades en sus países y tratan de buscar las mejores soluciones para la Comunidad Internacional. Geopolítica, seguridad nacional e internacional, comercio y desarrollo económico, la importancia de la internacionalización desde la óptica regional y local, el empleo juvenil, la educación, el comercio internacional, el rol de los organismos internacionales, mercados energéticos y desarrollo sostenible, desarrollo regional, el papel de los emprendedores, el liderazgo de la mujer en el nuevo contexto global o la importancia de las empresas en la contribución al bienestar de nuestras naciones serán analizadas para tratar de armar un cuerpo de propuestas que contribuyan a la gobernanza y desarrollo de nuestras naciones. -

Press Release

Press Release Xella Opens A New Plant for Gypsum Fibreboards in Spain Santander/Duisburg, 26 June 2013 – Today in the presence of the Regional Government President of Cantabria, Ignacio Diego, the Duisburg-based building materials group Xella will officially open the new production plant in Orejo, located near the Cantabrian capital of Santander, Northern Spain. The production plant will manufacture high quality gypsum fibreboards and will lay the foundations for further profitable growth of Fermacell GmbH, a subsidiary of Xella . At the start of 2012, Xella submitted a bid in a public auction for the newly built but unfinished plant in Orejo, previously owned by GFB Cantabria S.A. In April, Xella won the bid for the purchase price of € 14.5 million. Another € 8 million have been invested for creating a state-of-the-art factory and the plant is now ready to work to its full production capacity. As a part of the official opening it was announced that further €8 million will be invested for expansion in the near future. The total investment will amount to around € 30 million. Fermacell intends to produce up to 12 million sqm of gypsum fibreboards every year and 60 new jobs will be created. Xella CEO Jan Buck-Emden says: “The reasons for expanding the production of gypsum fiberboards has been the increased market demand, which has been rising for years, and the considerable additional sales potential in all product segments which are faced with extensive utilization of existing factories. With the quantities we produce in Spain we are going to supply the large construction markets in France, Great Britain and Scandinavia.” Moreover, our presence on the Spanish market will contribute to strengthening of our market positions in Europe.