White Chuck Road Repair Revised Environmental Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suspended-Sediment Concentration in the Sauk River, Washington, Water Years 2012-13

Prepared in cooperation with the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe Suspended-Sediment Concentration in the Sauk River, Washington, Water Years 2012-13 By Christopher A. Curran1, Scott Morris2, and James R. Foreman1 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Washington Water Science Center, Tacoma, Washington 2 Department of Natural Resources, Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, Darrington, Washington Photograph of glacier-derived suspended sediment entering the Sauk River immediately downstream of the Suiattle River mouth (August 5, 2014, Chris Curran). iii Introduction The Sauk River is one of the few remaining large, glacier-fed rivers in western Washington that is unconstrained by dams and drains a relatively undisturbed landscape along the western slope of the Cascade Range. The river and its tributaries are important spawning ground and habitat for endangered Chinook salmon (Beamer and others, 2005) and also the primary conveyors of meltwater and sediment from Glacier Peak, an active volcano (fig. 1). As such, the Sauk River is a significant tributary source of both fish and fluvial sediment to the Skagit River, the largest river in western Washington that enters Puget Sound. Because of its location and function, the Sauk River basin presents a unique opportunity in the Puget Sound region for studying the sediment load derived from receding glaciers and the potential impacts to fish spawning and rearing habitat, and downstream river-restoration and flood- control projects. The lower reach of the Sauk River has some of the highest rates of incubation mortality for Chinook salmon in the Skagit River basin, a fact attributed to unusually high deposition of fine-grained sediments (Beamer, 2000b). -

Continuing Education Summer 2017 Catalog

2017 SUMMER 2017 REGISTRATION FORM 2 0 1 7 2 5 Otis ID# /SSN (required for CT or CR) M/F Birthdate (mm/dd/yy) Year (Semester) Session Open House Legal Last Name Legal First Name MI Home Address (Required) Apartment Sunday, May 21, 2017 1 -3 pm City State Zip Elaine & Bram Goldsmith Campus Mailing Address (If different from Home Address) Apartment 9045 Lincoln Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90045 City State Zip 310-665-6850 Cell Work Landline Cell Emergency # Attend free information sessions on: Digital Media Arts and Graphic Design Email Address > Get information on Certificate Programs and *All above information is required to register. Incomplete forms will not be processed. Enter your courses below Summer of Art Reg# (ex: 25000; not "X" number) Course Title Tuition non-credit > Meet with instructors and program representatives certificate 2 5 credit > Tour the facilities non-credit 2 5 certificate > Participate in a drawing for a free Continuing Education credit course ($514 or less) Check#: Amount: $50 Early Bird Discount (Where Applicable) MC /Visa/AmEx/Disc#: > Register for most courses at $50 Early Bird discount 3-Digit Other Discounts Exp. Date: Billing Zip: Security Code on back Subtotal (Please note: Although all instructors are invited to attend the Open House, their Cardholder's Name: participation is not guaranteed; please call ahead if you are hoping to meet a particular Non-refundable Do you need Otis Goldsmith campus parking? yes Registration Fee if $25.00 instructor at the Open House.) no semester tuition totals $101 or more (no fee for children ages 5-12) $14.00 For further information, please call 310-665-6850, ext. -

Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization And

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Washington Fish and Wildlife Office 510 Desmond Dr. SE, Suite 102 Lacey, Washington 98503 In Reply Refer To: AUG 1 6 2011 13410-2011-F-0141 13410-2010-F-0175 Daniel M. Mathis, Division Adnlinistrator Federal Highway Administration ATIN: Jeff Horton Evergreen Plaza Building 711 Capitol Way South, Suite 501 Olympia, Washington 98501-1284 Michelle Walker, Chief, Regulatory Branch Seattle District, Corps of Engineers ATIN: Rebecca McAndrew P.O. Box 3755 Seattle, Washington 98124-3755 Dear Mr. Mathis and Ms. Walker: This document transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Biological Opinion (Opinion) based on our review of the proposed State Route 20, Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization and Chronic Environmental Deficiency Project in Skagit County, Washington, and its effects on the bull trout (Salve linus conjluentus), marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus), northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina), and designated bull trout critical habitat, in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.) (Act). Your requests for initiation of formal consultation were received on February 3, 2011, and January 19,2010. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - Seattle District (Corps) provided information in support of "may affect, likely to adversely affect" determinations for the bull trout and designated bull trout critical habitat. On April 13 and 14, 2011, the FHWA and Corps gave their consent for addressing potential adverse effects to the bull trout and bull trout critical habitat with a single Opinion. -

LCSH Section W

W., D. (Fictitious character) William Kerr Scott Lake (N.C.) Waaddah Island (Wash.) USE D. W. (Fictitious character) William Kerr Scott Reservoir (N.C.) BT Islands—Washington (State) W.12 (Military aircraft) BT Reservoirs—North Carolina Waaddah Island (Wash.) USE Hansa Brandenburg W.12 (Military aircraft) W particles USE Waadah Island (Wash.) W.13 (Seaplane) USE W bosons Waag family USE Hansa Brandenburg W.13 (Seaplane) W-platform cars USE Waaga family W.29 (Military aircraft) USE General Motors W-cars Waag River (Slovakia) USE Hansa Brandenburg W.29 (Military aircraft) W. R. Holway Reservoir (Okla.) USE Váh River (Slovakia) W.A. Blount Building (Pensacola, Fla.) UF Chimney Rock Reservoir (Okla.) Waaga family (Not Subd Geog) UF Blount Building (Pensacola, Fla.) Holway Reservoir (Okla.) UF Vaaga family BT Office buildings—Florida BT Lakes—Oklahoma Waag family W Award Reservoirs—Oklahoma Waage family USE Prix W W. R. Motherwell Farmstead National Historic Park Waage family W.B. Umstead State Park (N.C.) (Sask.) USE Waaga family USE William B. Umstead State Park (N.C.) USE Motherwell Homestead National Historic Site Waahi, Lake (N.Z.) W bosons (Sask.) UF Lake Rotongaru (N.Z.) [QC793.5.B62-QC793.5.B629] W. R. Motherwell Stone House (Sask.) Lake Waahi (N.Z.) UF W particles UF Motherwell House (Sask.) Lake Wahi (N.Z.) BT Bosons Motherwell Stone House (Sask.) Rotongaru, Lake (N.Z.) W. Burling Cocks Memorial Race Course at Radnor BT Dwellings—Saskatchewan Wahi, Lake (N.Z.) Hunt (Malvern, Pa.) W.S. Payne Medical Arts Building (Pensacola, Fla.) BT Lakes—New Zealand UF Cocks Memorial Race Course at Radnor Hunt UF Medical Arts Building (Pensacola, Fla.) Waʻahila Ridge (Hawaii) (Malvern, Pa.) Payne Medical Arts Building (Pensacola, Fla.) BT Mountains—Hawaii BT Racetracks (Horse racing)—Pennsylvania BT Office buildings—Florida Waaihoek (KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa) W-cars W star algebras USE Waay Hoek (KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa : USE General Motors W-cars USE C*-algebras Farm) W. -

WDFW Wildlife Program Bi-Weekly Report August 1-15, 2020

Wildlife Program – Bi-weekly Report August 1 to August 15, 2020 DIVERSITY DIVISION HERE’S WHAT WE’VE BEEN UP: 1) Managing Wildlife Populations Fishers: Fisher reintroduction project partners from Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the National Park Service, Conservation Northwest, Calgary Zoo, and United States Forest Service recently initiated a genetic analysis of fishers to predict the effect of augmenting ten new fishers to Olympic National Park. One main goal of the analysis is to determine how the success of the augmentation could differ depending on whether the fishers came from British Columbia versus; two genetically different source-populations. Using existing genotypes from British Columbia and Alberta fishers, this analysis will provide insights into the best source population of fishers to use for the planned augmentation to the Olympic National Park, where 90 fishers from British Columbia were reintroduced from 2008 to 2010. A 2019 genetic analysis of fishers on the Olympic Peninsula (based on hair samples collected at baited hair-snare and camera stations from 2013-2016) indicated that genetic diversity of the Olympic fisher population had declined slightly and would be expected to decline further in the future, which could put that population at risk. An augmentation of new fishers could restore this genetic diversity and this new analysis of the effects of releasing more British Columbia versus Alberta fishers into this population will help us decide the best source population and the best implementation approach. 2) Providing Recreation Opportunities Nothing for this installment. 3) Providing Conflict Prevention and Education Nothing for this installment. 4) Conserving Natural Areas Nothing for this installment. -

Structure and Petrology of the Deer Peaks Area Western North Cascades, Washington

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Winter 1986 Structure and Petrology of the Deer Peaks Area Western North Cascades, Washington Gregory Joseph Reller Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Reller, Gregory Joseph, "Structure and Petrology of the Deer Peaks Area Western North Cascades, Washington" (1986). WWU Graduate School Collection. 726. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/726 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRUCTURE AMD PETROLOGY OF THE DEER PEAKS AREA iVESTERN NORTH CASCADES, WASHIMGTa^ by Gregory Joseph Re Her Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requiremerjts for the Degree Master of Science February, 1986 School Advisory Comiiattee STRUCTURE AiO PETROIDGY OF THE DEER PEAKS AREA WESTERN NORTIi CASCADES, VC'oHINGTON A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Western Washington University In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Gregory Joseph Re Her February, 1986 ABSTRACT Dominant bedrock mits of the Deer Peaks area, nortliv/estern Washington, include the Shiaksan Metamorphic Suite, the Deer Peaks unit, the Chuckanut Fontation, the Oso volcanic rocks and the Granite Lake Stock. Rocks of the Shuksan Metainorphic Suite (SMS) exhibit a stratigraphy of meta-basalt, iron/manganese schist, and carbonaceous phyllite. Tne shear sense of stretching lineations in the SMS indicates that dioring high pressure metamorphism ttie subduction zone dipped to the northeast relative to the present position of the rocks. -

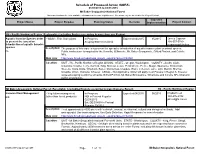

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2015 to 03/31/2015 Mt Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R6 - Pacific Northwest Region, Regionwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Region) Aquatic Invasive Species order - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:04/2015 05/2015 James Capurso to prevent the spread or Scoping Start 05/05/2014 208-557-5780 introduction of aquatic invasive [email protected] species Description: The purpose of this order is to prevent the spread or introduction of aquatic invasive plant or animal species. CE Public involvement is targeted for the Umatilla, Willamette, Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie, Gifford Pinchot, and Colville NFs. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=44360 Location: UNIT - R6 - Pacific Northwest Region All Units. STATE - Oregon, Washington. COUNTY - Asotin, Clark, Columbia, Cowlitz, Ferry, Garfield, King, Klickitat, Lewis, Pend Oreille, Pierce, Skagit, Skamania, Snohomish, Stevens, Walla Walla, Whatcom, Baker, Clackamas, Douglas, Grant, Jefferson, Lane, Linn, Marion, Morrow, Umatilla, Union, Wallowa, Wheeler. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Order will apply to all Forests in Region 6, however targeted scoping is with the Umatilla, Gifford Pinchot, Mt. Baker/Snoqualmie, Willamette and Colville NFs tribal and public scoping lists. Mt Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R6 - Pacific Northwest Region Invasive Plant Management - Vegetation management In Progress: Expected:04/2015 05/2015 Phyllis Reed EIS (other than forest products) NOI in Federal Register 360-436-2332 02/28/2012 [email protected] Est. -

Mt Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest EA CE

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2007 to 09/30/2007 Mt Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Aerial Application of Fire - Fuels management In Progress: Expected:08/2007 08/2007 Christopher Wehrli Retardant 215 Comment Period Legal 202-205-1332 EA Notice 07/28/2006 [email protected] Description: The Forest Service proposes to continue the aerial application of fire retardant to fight fires on National Forest System lands. An environmental analysis will be conducted to prepare an Environmental Assessment on the proposed action. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/retardant/index.html Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. Nation Wide. R6 - Pacific Northwest Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Aquatic Outfitter and Guide - Special use management Developing Proposal Expected:08/2008 01/2009 Don Gay Special Use Permits Est. Scoping Start 11/2007 360-856-5700 CE [email protected] Description: Issuance of special use permits for outfitter and guides using the N.F. Nooksack, Skagit, Sauk, Skykomish, and Cispus Rivers. Location: UNIT - Mt Baker Ranger District, Darrington Ranger District, Skykomish Ranger District, Cowlitz Ranger District. STATE - Washington. COUNTY - Lewis, Skagit, Snohomish, Whatcom. LEGAL - T40NR6E, T39NR6 and 7E, T39NR7E, T35NR8,9,10E, T36NR11E, T31-35NR10E, T32NR9E, T27NR9 and 10E, T11NR5,6,7, and 8E. N. F. Nooksack, Skagit, Sauk, Skykomish, and Cispus Rivers. -

Yakama-Cowlitz Trail: Ancient and Modern Paths Across the Mountains

COLUMBIA THE MAGAZINE OF NORTHWEST HISTORY ■ SUMMER 2018 Yakama-Cowlitz Trail: Ancient and modern paths across the mountains North Cascades National Park celebrates 50 years • Explore WPA Legacies A quarterly publication of the Washington State Historical Society TWO CENTURIES OF GLASS 19 • JULY 14–DECEMBER 6, 2018 27 − Experience the beauty of transformed materials • − Explore innovative reuse from across WA − See dozens of unique objects created by upcycling, downcycling, recycling − Learn about enterprising makers in our region 18 – 1 • 8 • 9 WASHINGTON STATE HISTORY MUSEUM 1911 Pacific Avenue, Tacoma | 1-888-BE-THERE WashingtonHistory.org CONTENTS COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History A quarterly publication of the VOLUME THIRTY-TWO, NUMBER TWO ■ Feliks Banel, Editor Theresa Cummins, Graphic Designer FOUNDING EDITOR COVER STORY John McClelland Jr. (1915–2010) ■ 4 The Yakama-Cowlitz Trail by Judy Bentley OFFICERS Judy Bentley searches the landscape, memories, old photos—and President: Larry Kopp, Tacoma occasionally, signage along the trail—to help tell the story of an Vice President: Ryan Pennington, Woodinville ancient footpath over the Cascades. Treasurer: Alex McGregor, Colfax Secretary/WSHS Director: Jennifer Kilmer EX OFFICIO TRUSTEES Jay Inslee, Governor Chris Reykdal, Superintendent of Public Instruction Kim Wyman, Secretary of State BOARD OF TRUSTEES Sally Barline, Lakewood Natalie Bowman, Tacoma Enrique Cerna, Seattle Senator Jeannie Darneille, Tacoma David Devine, Tacoma 14 Crown Jewel Wilderness of the North Cascades by Lauren Danner Suzie Dicks, Belfair Lauren14 Danner commemorates the 50th22 anniversary of one of John B. Dimmer, Tacoma Washington’s most special places in an excerpt from her book, Jim Garrison, Mount Vernon Representative Zack Hudgins, Tukwila Crown Jewel Wilderness: Creating North Cascades National Park. -

Seasonal Distribution and Habitat Associations of Salmonids With

Seasonal Distribution and Habitat Associations of Salmonids with Extended Juvenile Freshwater Rearing in Different Precipitation Zones of the Skagit River, WA January, 2020 Erin D. Lowery1*, Jamie N. Thompson1, Ed Connor2, Dave Pflug2, Bryan Donahue1, Jon- Paul Shannahan3 Introduction a freshwater rearing period lasting more than one Anadromous salmonids (Salmonidae spp.) year (Quinn 2005, SRSC and WDFW 2005). experience a variety of freshwater and marine As climate change progresses, the timing and habitats through the completion of their life cycle. magnitude of hydrologic cycles are expected to shift Certain life stages and habitats have been associated significantly, and these changes could dramatically with critical periods of growth or survival, wherein affect the overall capacity of watersheds to support the growth performance achieved within the critical anadromous salmonids as well as the spatial- period is highly and positively correlated to survival temporal distribution of habitats that support the through subsequent life stages. Alternatively, positive growth trajectories that improve the survival disproportionately high or variable mortality might of these fishes (Battin et al. 2007; Schindler et al. be associated with these periods, but the variability 2008). Pacific salmonids, Oncorhynchus and in mortality is strongly mediated by growth or Salvelinus spp., that rely on extended freshwater environmental conditions (Beamish and Mahnken rearing like steelhead O. mykiss, spring, summer, and 2001). The timing and location of these critical fall Chinook salmon O. tshawytscha, Coho salmon O. periods can vary considerably among species, kisutch, Sockeye salmon O. nerka, and Bull Trout S. populations, among years within populations, and confluentus are likely to be more vulnerable to could operate on the growth performance achieved climatic shifts in hydrology and thermal regime than in either freshwater (e.g., Steelhead, Ward et al. -

Structure and Petrology of the Grandy Ridge-Lake Shannon Area, North Cascades, Washington Moira T

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Winter 1986 Structure and Petrology of the Grandy Ridge-Lake Shannon Area, North Cascades, Washington Moira T. (Moira Tracey) Smith Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Moira T. (Moira Tracey), "Structure and Petrology of the Grandy Ridge-Lake Shannon Area, North Cascades, Washington" (1986). WWU Graduate School Collection. 721. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/721 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASTER'S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master's degree at Western Washington University, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood, however, that any copying or publication of this thesis for commercial purposes, or for financial gain, shall not be allowed without my written permission . Bellin^hum, W'Mihington 9HZZS □ izoai aTG-3000 STRUCTURE AND PETROLOGY OF THE GRANDY RIDGE-LAKE SHANNON AREA, NORTH CASCADES, WASHINGTON By Moira T. Smith Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science aduate School ADVISORY COMMITEE: Chairperson MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. -

Distribution and Abundance of Mountain Goats Within the Ross Lake Watershed, North Cascades National Park Service Complex

' I ; q£ 04. & 9) -~o3 Distribution and Abundance of Mountain Goats within the Ross Lake Watershed, North Cascades National Park Service Complex Final Report to Skagit Environmental Endowment Commission Sarah J. Welch Robert C. Kuntz II Ronald E. Holmes Roger G. Christophersen North Cascades National Park Service Complex 2105 State Route 20 Sedro-Woolley, Washington 98284-9314 December 1997 1997 SEC #10 . ' Table of Contents I. Introduction 1 2. Study Area 3. Methods 3 4. Results. 4 5. Discussion 5 6. Recommendations 6 7. Literature Cited 7 List of Figures 1. Figure 1: Mountain goat study area in Ross Lake watershed, North Cascades National Park Service Complex (1996-1997) 2 List of Tables 1. Table l: Mountain goat observations. 4 2. Table 2: Habitat characteristics where mountain goats were observed 5 Distribution and Abundance of Mountain Goats within the Ross Lake Watershed, North Cascades National Park Service Complex Introduction Mountain goats (Oreamnus americanus) are native to northwestern North America and can be found throughout the North Cascades National Park Service Complex (NOCA). Their habitat requirements are quite specific and suitable habitat is patchily distributed across the landscape. During a11 seasons, mountain goat habitat is characterized by steep, rocky terrain. Summer habitat is generally above 1525 m (5000 ft) elevation, and features rock outcrops in or near subalpine meadows and forest (Welch, 1991; Holmes, 1993; Schoen and Kirchoff, 1981; NCASI, 1989; Chadwick, 1983; Benzon and Rice, 1988). Many mountain goat populations in Washington have declined during the last 20 years. Although specific causes have not been identified, several factors may have contributed to the regional decline.