As My First Agent Rightly Said to Me, Go with the Material, Not the Money

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Digest Document 3

ighty first-year students were of medical school is going to be quite welcomed into the medical different from anything you’ve done artmouth Medical School has Eprofession with the white coat before. It’s not going to be like high received an $11.6 million ceremony October 26, which intro- school and it’s not going to be like Daward from the National duced the new students to the privi- college.” He characterized this period Institutes of Health (NIH) to establish leges and responsibilities associated as an important transition in the stu- a nationally recognized center of bio- with becoming a physician. dents’ lives, an experience that is not medical research excellence in only intellectual but also profoundly immunology and inflammation.The emotional.“It’s an attitudinal transi- five-year grant will support collabora- tion,” he said,“for you will notice a tive projects at DMS in conjunction change in the way you study and a with the University of New change in the way you think about Hampshire (UNH), promoting people.” research opportunities for biomedical Baldwin said that medical training investigators in New Hampshire with prepares physicians to perform two broad potential for understanding and basic tasks: relieve suffering and pro- treating diseases of the immune sys- long life. Physicians, therefore, have tem and cancer. Flying SquirrelFlying Graphics limited expertise and are not meant to The funds are awarded through a Dean John C. Baldwin, MD, welcomes MD/PhD be judges, policemen or moral guides special program called COBRE, -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

Arts&Sciences

CALENDAR College of Liberal Arts and Sciences The University of Iowa School of Music is 240 Schaeffer Hall celebrating its centennial throughout 2006-07; The University of Iowa visit www.uiowa.edu/~music for a calendar Iowa City, Iowa 52242-1409 of events. November E-mail: [email protected] Visit the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences REQUIEM at www.clas.uiowa.edu By Giuseppe Verdi A School of Music, Division of Performing Arts, centennial event featuring the University Symphony Orchestra and Choirs with alumni Arts&Sciences guest soloists FALL 2006 Arts & Sciences is published for alumni and friends of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences December at The University of Iowa. It is produced by the Offi ce of the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and by the Offi ce of University Relations Publications. WINTER COMMENCEMENT Address changes: Readers who wish to change their mailing address for JanuaryFebruary Arts & Sciences may call Alumni Records at 319-335-3297 or 800-469-2586; or send an e-mail to [email protected]. INTO THE WOODS Music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim DEAN Linda Maxson Department of Theatre Arts, Division of E XECUTIVE E DITOR Carla Carr Performing Arts M ANAGING E DITOR Linda Ferry February CONSULTING E DITOR Barbara Yerkes M AIA STRING QUARTET DESIGNER Anne Kent COLLABORATION P HOTOGRAPHER Tom Jorgensen Department of Dance and School of Music, CONTRIBUTING FEATURE WRITERS Division of Performing Arts Peter Alexander, Winston Barclay, Lori Erickson, Richard Fumerton, Gary W. May Galluzzo, Lin Larson, Jen Knights, Sara SPRING COMMENCEMENT Epstein Moninger, David Pedersen COVER P HOTO: Art Building West provides a study June in refl ected light. -

Primetime • Tuesday, April 17, 2012 Early Morning

Section C, Page 4 THE TIMES LEADER—Princeton, Ky.—April 14, 2012 PRIMETIME • TUESDAY, APRIL 17, 2012 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 ^ 9 Eyewitness News Who Wants to Be a Last Man Standing (7:31) Cougar Town Dancing With the Stars (N) (S) (Live) (9:01) Private Practice Erica’s medical Eyewitness News Nightline (N) (CC) (10:55) Jimmy Kimmel Live “Dancing WEHT at 6pm (N) (CC) Millionaire (CC) (N) (CC) (N) (CC) (CC) condition gets worse. (N) (CC) at 10pm (N) (CC) With the Stars”; Ashanti. (N) (CC) # # News (N) (CC) Entertainment To- Last Man Standing (7:31) Cougar Town Dancing With the Stars (N) (S) (Live) (9:01) Private Practice Erica’s medical News (N) (CC) (10:35) Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live “Dancing With the WSIL night (N) (CC) (N) (CC) (N) (CC) (CC) condition gets worse. (N) (CC) (N) (CC) Stars”; Ashanti. (N) (CC) $ $ Channel 4 News at Channel 4 News at The Biggest Loser The contestants re- The Voice “Live Eliminations” Vocalists Fashion Star “Out of the Box” The design- Channel 4 News at (10:35) The Tonight Show With Jay (11:37) Late Night WSMV 6pm (N) (CC) 6:30pm (N) (CC) view their progress. (N) (CC) face elimination. (N) (S) (Live) (CC) ers push creative boundaries. (N) 10pm (N) (CC) Leno (CC) With Jimmy Fallon % % Newschannel 5 at 6PM (N) (CC) NCIS “Rekindled” The team investigates a NCIS: Los Angeles “Lone Wolf” A discov- Unforgettable “Trajectories” A second NewsChannel 5 at (10:35) Late Show With David Letter- Late Late Show/ WTVF warehouse fire. -

James Newton Howard

JAMES NEWTON HOWARD AWARDS/NOMINATIONS SATURN AWARD (2009) DARK KNIGHT Best Music * ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2009) DEFIANCE Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (2008) THE DARK KNIGHT Music * BROADCAST FILM CRITICS ASSOCIATION THE DARK KNIGHT NOMINATION (2008) Best Composer * GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION (2008) DEFIANCE Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD AWARD (2008) DARK KNIGHT Best Score Soundtrack Album* iTUNES AWARD (2008) DARK KNIGHT Best Score* WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD (2008) CHARLIE WILSON’S WAR Film Composer of the Year MICHAEL CLAYTON I AM LEGEND ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2008) MICHAEL CLAYTON Best Original Score INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2007) Film Composer of the Year GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2007) BLOOD DIAMOND Be st Score Soundtrack Album GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION (2005) KING KONG Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2005) THE VILLAGE Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2002) “Main Titles” from SIGNS Best Instrumental Composition EMMY AWARD (2001) GIDEON’S CROSSING Outstanding Main Title Theme Music The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 JAMES NEWTON HOWARD GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2000) “The Egg Travels” from DINOSAUR Best Instrumental Composition ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1997) MY BEST FRIEND’S WEDDING Best Original Musical or Comedy Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1997) "For The First Time" Best Song Written for a Motion Picture or Television* from ONE FINE DAY ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1996) "For The First Time" GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION from ONE FINE DAY (1996) Best Original Song* ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) "Look What Love Has Done" GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1994) from JUNIOR Best Original Song* ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1993) THE FUGITIVE Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOM INATION (1991) THE PRINCE OF TIDES Best Original Score EMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1995) E.R. -

R.I.P. B.B. King 1925-2015

June 2015 www.torontobluessociety.com Published by the TORONTO BLUES SOCIETY since 1985 [email protected] Vol 31, No 6 PHOTO COURTESY SHOWTIME MUSIC ARCHIVES (TORONTO) SHOWTIME MUSIC COURTESY PHOTO R.I.P. B.B. King 1925-2015 CANADIAN PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT #40011871 BB Remembered John’s Blues Picks Talent Search Finals Loose Blues News Selena Evangeline Event Listings 2 MapleBlues June 2015 www.torontobluessociety.com MARK YOUR CALENDAR PHOTO COURTESY SHOWTIME MUSIC ARCHIVES (TORONTO) SHOWTIME MUSIC COURTESY PHOTO Dave "Daddy Cool" Booth will be making his first DJ appearance in many years at the TBS 30th bash at the Palais Royale on July 16 spinning some of his favourite blues tracks for the dinner crowd and Jack de Keyzer will be playing Sundown Solo Sets for both early ticket and concert ticket holders. Saturday, June 20 (afternoon), Dan Aykroyd Wine Tasting, Summerhill LCBO (10 Scrivener Square, just outside the Summerhill subway) Performance by David Owen Barbara Klunder has provided the new imagery for the 29th Women's Blues Revue to be held November 28 at Saturday, June 20 Massey Hall and Charter Member tickets go on sale Tuesday, June 9th at 10am! (preferred seating and 20% off). 2-5pm TBS Talent To retrieve the required promo code, please contact the TBS office. If you're not a member yet, join now to take Search Finals, Distillery advantage of these substantial savings. District (part of the TD Toronto Jazz Festival) Michael Sloski and musical director Lance Saturday, November 28, Massey Hall, th Johanna Pavia & Anderson. Sundown Solo sets by Jack Women's Blues Revue. -

01-05-1984.Pdf

i 4 * Cass City Jaeger auto plant Curse becomes a blessing You may be in a new excited folks in ‘33 for Christian church school state voting district Page 10 Page 16 Page 16 IC JI 1 CASS CITY CHRONICLE VOLUME 77, NUMBER 38 CASS CITY,MICHIGAN -THURSDAY, JANUARY 5,1984 Twenty-five cents 16 PAGES PLUS SUPPLEMENT 3 departments battle fire $65,000 loss in ~ large barn blaze U “It went through the 1881 mated the loss at $35,000 to tools. Gagetown department with fire and it ain’t going to the barn and $30,000 to the The fire was discovered a pumper and tanker and make it through the next contents. by Paul Hutchinson, Hutch- thetanker Car0 .I department with a one,” Dean Hutchinson The contents included inson’s nephew, who lives commented last Wednes- nine registered Suffolk next door. He called the fire The two assisting depart- day as he watched his barn sheep, which belonged to department and his ments left about 4 p.m. Elk- burn. the Hutchinsons’ son. Scott, mother, Geraldine, ran land firemen departed one beef steer, a dog and next door to tell Nancy about 7 p.m. Part of the 60-by-80 foot puppies, a few chickens, ap- Hutchinson. Root said about 21,000 structure was more than proximately 1,000 bales of gallons of water were used 100 years old. The barn, Root said that when Paul straw and at least 3,000 of Hutchinson first saw the in fighting the blaze. owned by Hutchinson and Although it was impossi- his wife, Nancy, was on hay, one gravity wagon and fire, it was burning in the one flatbed wagon, a grain vicinity where the electri- ble to save the barn, fire- Spence Road, northwest of elevator, hay elevator, men from the three depart- Cass City. -

The Museum of Modern Art Presents a Discussion of the HBO Series the Sopranos with the Series Writer/Director David Chase and No

MoMA | press | Releases | 2001 | Discussion on The Sopranos Page 1 of 3 For Immediate Release February 2001 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART HOSTS DISCUSSION ON THE SOPRANOS Discussion with David Chase and media writer Ken Auletta February 12, 2001 The Sopranos February 3-13, 2001 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theatre 1 The Museum of Modern Art presents a discussion of the HBO series The Sopranos with the series writer/director David Chase and noted media writer and author Ken Auletta, February 12, 2001 at 6:00 p.m. at the Roy and Niuta Titus Theatre 1. Recording the domestic dramas and business anxieties of family living the bourgeois life in a pleasant New Jersey suburb, The Sopranos is a saga of middle-class life in America at the turn of the century. Chronicled in twenty-six hour-long episodes, the first two seasons from the series will be shown in two four-day sequences at The Museum of Modern Art, from February 3-13 at the Roy and Niuta Titus Theatre 1. "The Sopranos is a cynical yet deeply felt look at this particular family man," remarks Laurence Kardish, Senior Curator, Department of Film and Video, who organized the program. "David Chase and his team have created a series distinguished by its bone-dry humor and understated, quirky, and stinging perspective - not usually seen on television." Renowned for his savvy profiles of power players in the media, Ken Auletta will join David Chase for a discussion of The Sopranos at The Museum on February 12. The Department of Film and Video gratefully acknowledges HBO for making the series available for public viewing. -

WRITING for EPISODIC TV from Freelance to Showrunner

WRITING FOR EPISODIC TV From Freelance to Showrunner Written by: Al Jean Brad Kern Jeff Melvoin Pamela Pettler Dawn Prestwich Pam Veasey John Wirth Nicole Yorkin Additional Contributions by: Henry Bromell, Mitch Burgess, Carlton Cuse, Robin Green, Barbara Hall, Al Jean, Amy Lippman, Dan O’Shannon, Phil Rosenthal, Joel Surnow, John Wells, Lydia Woodward Edited by: John Wirth Jeff Melvoin i Introduction: Writing for Episodic Television – A User’s Guide In the not so distant past, episodic television writers worked their way up through the ranks, slowly in most cases, learning the ropes from their more-experienced colleagues. Those days are gone, and while their passing has ushered in a new age of unprecedented mobility and power for television writers, the transition has also spelled the end of both a traditional means of education and a certain culture in which that education was transmitted. The purpose of this booklet is twofold: first, to convey some of the culture of working on staff by providing informal job descrip- tions, a sense of general expectations, and practical working tips; second, to render relevant WGA rules into reader-friendly lan- guage for staff writers and executive producers. The material is organized into four chapters by job level: FREE- LANCER, STAFF WRITER/STORY EDITOR, WRITER-PRODUCER, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER. For our purposes, executive producer and showrunner are used interchangeably, although this is not always the case. Various appendices follow, including pertinent sections of the WGA Minimum Basic Agreement (MBA). As this is a booklet, not a book, it does not make many distinc- tions among the different genres found in episodic television (half- hour, animation, primetime, cable, first-run syndication, and so forth). -

TODD A. DOS REIS, A.S.C. Director of Photography

TODD A. DOS REIS, A.S.C. Director of Photography Television Council of Dads | NBC/Universal| Jerry Bruckheimer | Season 1 directors| James Strong, Jonathan Brown, Lily Mariye, Nicole Rubio, Gearey McLeod, Benny Boom executive producers| Tony Phelan, Joan Rater, Jonathan Brown, Jonathan Littman, James Oh, cast| Sarah Wayne Callies, J. August Richards, Clive Standen, Michael O’Neil, Michele Weaver David Makes Man | OWN | Warner Horizon| Pilot & Season 1 directors | Michael Williams, Daina Reid executive producers| Tarell Alvin McCraney, Michael B. Jordan, Oprah Winfrey, Dee Harris Lawrence cast | Akili McDowell, Alana Arenas, Isaiah Johnson, Travis Coles, Phylicia Rashad • PEABODY AWARD WINNER 2020 Crazy Ex Girlfriend | CW Network | CBS | Season 1, 2 and 3 directors| Marc Webb, Erin Erlich, Stuart McDonald, Alex Hardcastle, Michael Schultz, Joseph Kahn executive producers | Aline Brosh McKenna, Rachel Bloom, Sarah Caplan cast | Rachel Bloom, Donna Lynne Champlin, Vincent Rodriguez, Pete Gardner, Vella Lovell Longmire | Netflix | Warner Horizon | Season 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6 directors | Chris Chulack | J. Michael Muro, Zetna Fuentes, Michael Offer, Magnus Martens executive producers | Greer Shephard | Hunt Baldwin | John Coveny | Pat McKee cast | Robert Taylor, Katee Sackhoff, Lou Diamond Phillips | Cassidy Freeman, Adam Bartley Entourage | HBO | Warner Bros.| Season 5, 6, 7 and 8 directors | Mark Mylod, Julian Farino, David Nutter, Ken Whittingham, Dan Attias, Tucker Gates executive producers | Mark Wahlberg, Doug Ellin, Stephen Levinson cast | Kevin Connolly, Adrian Grenier, Kevin Dillon, Jerry Ferrara, Jeremy Piven Necessary Roughness | USA Network | Season 3 directors | Kevin Dowling , Kevin Hooks, Tim Hunter, James Hayman, Craig Shapiro executive producers | Liz Kruger, Craig Shapiro, Jeffrey Lieber, Kelly Manners cast | Callie Thorne, Scott Cohen, Mechad Brooks, John Stamos, David Anders, Autumn Reeser Suburgatory | ABC | Warner Bros. -

Engineering (Mail Stop No

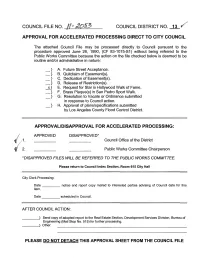

COUNCIL FILE NO. /f- t20S3 COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 13 fl"'/ APPROVAl FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCil The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1075-S1) without being referred to the Public Works Committee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: _} A. Future Street Acceptance. _} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). _} C. Dedication of Easement(s). _} D. Release of Restriction(s). _15] E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. _} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. _} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. _} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAl/DISAPPROVAl FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* /,1. Council Office of the District '/ 2. Public Works Committee Chairperson *DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: ____~ Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. ____~ Other: PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCil FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS- E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council DEC 0 7 2011 Ofthe City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C.