Fisheries Certification in the Era of Market Civilization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conductor's Guide to the Da Vinci Requiem by Cecilia Mcdowall

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2020 A Conductor’s Guide to the Da Vinci Requiem by Cecilia McDowall Jantsen Blake Touchstone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Touchstone, J. B.(2020). A Conductor’s Guide to the Da Vinci Requiem by Cecilia McDowall. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5920 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO THE DA VINCI REQUIEM BY CECILIA MCDOWALL by Jantsen Blake Touchstone BaChelor of MusiC Mississippi College, 2011 BaChelor of MusiC Education Mississippi College, 2013 Master of MusiC Mississippi College, 2013 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of MusiCal Arts in Conducting SChool of MusiC University of South Carolina 2020 ACCepted by: AliCia W. Walker, Major Professor Jabarie Glass, Committee Member Andrew Gowan, Committee Member J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, ViCe Provost and Dean of the Graduate SChool © Copyright by Jantsen Blake Touchstone, 2020 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my wife, Amy Touchstone, for your endless support, patience, love, and saCrifiCe. Your support, patience and understanding have allowed me to complete this projeCt; I thank you. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would begin by thanking CeCilia MCDowall for writing such wonderful choral musiC and allowing such aCCess to her life and thoughts. -

Task Force on Fish/Crab Prices

New Beginnings: Bringing Stability and Structure to Price Determination in the Fishing Industry Report of the Task Force on Fish/Crab Price Settlement Mechanisms in the Fishing Industry Collective Bargaining Act January 15, 1998 Cover Photo: K. Bruce Lane ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Task Force expresses our gratitude to everyone who made a contribution to our work. We are particularly indebted to those fish harvesters, fish processors and other interested parties who took the time to meet with us and make presentations during our consultations around the Province. These presentations were invaluable in providing us with an understanding of the issues arising from our Terms of Reference. Throughout the process, the Task Force worked closely with fish harvesters and processors and with their representatives. Senior executives of the FFAW/CAW and FANL participated with the Task Force in visits to Iceland, Quebec, British Columbia and Japan. The Task Force expresses our profound appreciation for the high level of cooperation and support which we received from: Mr. Earle McCurdy, the President of the FFAW/CAW; Mr. Reg Anstey, Secretary/Treasurer of the FFAW/CAW; and Mr. Alastair O’Reilly, the President of the Fisheries Association of Newfoundland and Labrador. It was through their efforts that we were able to achieve a high level of consensus. There are a number of people who assisted by facilitating our visits to Iceland, Quebec, British Columbia, and Japan. In this regard, particular thanks are expressed to Mr. Jon Bergs, Honorary Consul General to the Canadian Consulate General in Iceland; Mr. Arni Kolbeinsson, Secretary General to the Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries; Mr. -

Canada's Cultural Media Policy and Newfoundland Music on the Radio

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2007 Canada’s Cultural Media Policy and Newfoundland Music on the Radio: Local Identities and Global Implications Sara Beth Keough University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Keough, Sara Beth, "Canada’s Cultural Media Policy and Newfoundland Music on the Radio: Local Identities and Global Implications. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/208 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sara Beth Keough entitled "Canada’s Cultural Media Policy and Newfoundland Music on the Radio: Local Identities and Global Implications." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Geography. Thomas L. Bell, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Lydia M. Pulsipher, John B. Rehder, Leslie C. Gay, Jr. -

Program on Application of Communications Satellites to Educational Development

PROGRAM ON APPLICATION OF COMMUNICATIONS SATELLITES TO EDUCATIONAL DEVELOPMENT WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Internal Memorandum No. 71/3 August 9, 1971 EDUCATIONAL ELECTRONIC INFORMATION DISSEMINATION AND BROADCAST SERVICES: HISTORY, CURRENT INFRASTRUCTURE AND PUBLIC BROADCASTING REQUIREMENTS 0 0 dai P. Singh 2 ACCItV UMBER TPBAp 4, , (NASA CR OR'T X OR AD NUMBER) (CATEGO This research is supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under Grant No. Y/NGL-26-008-054. This memorandum is primarily for internal distribution and does not necessarily represent the views of either the research team as a whole or the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. ,NATIONALReproduced TECHNICAL by " .INFORMATION SERVICE' Spfs,,fiI , Va. 22151 , PROGRAM ON APPLICATION OF COMMUNICATIONS SATELLITES TO EDUCATIONAL DEVELOPMENT WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Internal Memorandum No. 71/3 August 9, 1971 EDUCATIONAL ELECTRONIC INFORMATION DISSEMINATION AND BROADCAST SERVICES: HISTORY, CURRENT INFRASTRUCTURE AND PUBLIC BROADCASTING REQUIREMENTS Jai P. Singh Robert P. Morgan This research is supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under Grant No. Y/NGL-26-008-054. This memorandum is primarily for internal distribution and does.not necessarily represent the views of either the research team as a whole or the National Aeronautics and'Space Administration. SUMMARY This memorandum describes the results of a study conducted on electronic educational information dissemination and broadcast services in the United States. Included are detailed discussions of the historical development and current infrastructure, both in terms of organization and physical plant, of the following services: educational radio broadcasting, educational television broadcasting, Instructional Television Fixed Services (ITFS), Information Retrieval (Dial Access) Television (IRTV), Closed-Circuit Television, Responsive Television and Cable Television. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number 295 21/12/15

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 295 21 December 2015 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 295 21 December 2015 Contents Introduction 4 Note to Broadcasters Future regulation of on-demand programme services 6 Notice of Sanction International Television Channel Europe Limited 7 Standards cases In Breach Channel 4 News Channel 4, 24 August 2015, 19:00 9 Alor Dishari Iqra Bangla, 31 August 2015, 22:00 14 Jimmy Swaggart The Classics SBN International, 7 July 2015, 17:00 22 The Simpsons Channel 4, 7 October 2015, 18:00 26 A League of Their Own Sky Sports 1, 14 October 2015, 19:30 29 Various programmes Starz, various dates and times 31 Resolved TFI Friday Channel 4, 23 October 2015, 20:53 34 Rick Jackson: The Big Drive Wave 105.2 FM, 23 October 2015, 18:00 36 Advertising Scheduling cases In Breach Advertising minutage Geo News, various dates and times 39 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 295 21 December 2015 Broadcast Licence Conditions cases In Breach Broadcasting licensees’ late and non-payment of licence fees 41 Providing a service in accordance with ‘Key Commitments’ EAVA FM (Leicester), 24 to 26 June 2015 42 Providing a service in accordance with ‘Key Commitments’ Access FM (Bridgwater), 9 to 11 September 2015 45 Fairness and Privacy cases Not in Breach Dispatches: Politicians for Hire Channel 4, 23 February 2015 47 Investigations Not in Breach 85 Complaints assessed, not investigated 86 Complaints outside of remit 95 Investigations List 97 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 295 21 December 2015 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003 (“the Act”), Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content as appear to it best calculated to secure the standards objectives1. -

Authentic First Peoples Resources for Grades 10-12 and Adult Learning

Authentic First Peoples Resources For Grades 10-12 and Adult Learning First Nations Education Steering Committee First Nations Schools Association Authentic First Peoples Resources for Grades 10 to 12 and Adult Learning Copyright © 2021, First Nations Education Steering Committee and First Nations Schools Association Copyright Notice No part of the content of this document may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including electronic storage, reproduction, execution, or transmission without the prior written permission of FNESC. First Nations Education Steering Committee and First Nations Schools Association #113 ‐ 100 Park Royal South, West Vancouver, BC V7T 1A2 604‐925‐6087 / 1‐877‐422‐3672 [email protected] Contents 3 Introduction 3 What Are Authentic First Peoples Texts? 4 The Power of Story 4 Common Themes in First Peoples Texts 5 Copyright and Protocol 5 Dealing with Sensitive Content 6 Using this Guide 7 Assessing Additional Texts 8 Additional Educator Resource Material 9 Resource Annotations 65 Index 67 Appendix: Resource Evaluation Form 2 First Nations Education Steering Committee & First Nations School Association Introduction The past two decades have seen a dramatic increase in the number of Indigenous texts. The First Nations Education Steering Committee (FNESC) and the First Nations Schools Association (FNSA) have developed tools to help educators in British Columbia (BC) make decisions about which resources might be appropriate for use with students. This guide expands on the resources referenced in the English First Peoples 10‐12 Teacher Resource Guide and Authentic First Peoples Resources for Use in K‐9 Classrooms (both available on fnesc.ca) to include annotated listings of authentic First Peoples texts that students in grades 10‐12 and adult learners can work with to meet provincial curriculum standards. -

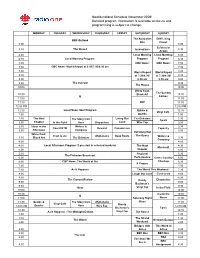

Newfoundland Schedule November 2009 Detailed Program Information Is Available at Cbc.Ca and Programming Is Subject to Change

Newfoundland Schedule November 2009 Detailed program information is available at cbc.ca and programming is subject to change. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY The Australian D/W Living BBC Outlook Bite Planet 5:00 5:00 Science in 5:30 The Strand Innovations 5:30 Action 6:00 Local Morning Local Morning 6:00 6:30 Local Morning Program Program Program 6:30 7:00 CBC News: CBC News: 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 6:30/7:30/8:30 am 7:30 8:00 World Report World Report 8:00 8:30 at 7:30/8:30/ at 7:30/8:30/ 8:30 9:00 9:30 am 9:30 am 9:00 9:30 The Current 9:30 The House 10:00 10:00 White Coat, The Sunday 10:30 Black Art 10:30 Q Edition 11:00 11:00 11:30 GO! 11:30 12:00 PM 12:00 PM 12:30 Local Noon Hour Program Quirks & 12:30 Vinyl Café 1:00 Quarks 1:00 1:30 The Next Living Out The Debaters 1:30 The Story from Spark 2:00 Chapter In the Field Here Dispatches Loud Wire Tap 2:00 2:30 Ideas in the Writers & 2:30 Your DNTO Rewind Canada Live Tapestry 3:00 Afternoon Company 3:00 Definitely Not White Coat, C'est la vie Afghanada Deep Roots The Opera Writers & 3:30 Black Art The Debaters 3:30 Company 4:00 4:00 4:30 Local Afternoon Program (3 pm start in selected markets) The Next 4:30 Musicraft 5:00 Chapter 5:00 5:30 Regional 5:30 The Fisheries Broadcast 6:00 Performance Cross Country 6:00 6:30 CBC News: The World at Six Checkup 6:30 A Propos 7:00 7:00 7:30 As It Happens The World This Weekend 7:30 8:00 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 8:00 8:30 8:30 The Current Review Randy Dispatches 9:00 9:00 Bachman's 9:30 9:30 Ideas Vinyl Tap In the Field 10:00 10:00 10:30 Inside the 10:30 Q 11:00 Saturday Night Music 11:00 11:30 Quirks & The Story from Afghanada Blues 11:30 Vinyl Café Randy 12:00 AM Quarks Here Wire Tap 12:00 AM Bachman's Tonic 12:30 12:30 As It Happens - The Midnight Edition Vinyl Tap The House 1:00 1:00 1:30 The Strand 1:30 The World Network Europe 2:00 Weekend 2:00 Bridges with This Week in 2:30 Africa Africa 2:30 3:30 BBC Doc BBC Doc 3:30 The Link 4:00 TBA 4:00 The State We Are In BBC 4:30 Assignment 4:30. -

%Urdgfdvwlqj ,Qtxlu\ 5Hsruw

%URDGFDVWLQJ ,QTXLU\5HSRUW 5HSRUW1R 0DUFK Commonwealth of Australia 2000 ISBN 1 74037 156 9 This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial use or sale requires prior written permission from AusInfo. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601. Publications Inquiries: Media and Publications Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Melbourne VIC 8003 Tel: (03) 9653 2244 Fax: (03) 9653 2303 Email: [email protected] General Inquiries: Tel: (03) 9653 2100 or (02) 6240 3200 An appropriate citation for this paper is: Productivity Commission 2000, Broadcasting, Report no. 11, AusInfo, Canberra. The Productivity Commission The Productivity Commission, an independent Commonwealth agency, is the Government’s principal review and advisory body on microeconomic policy and regulation. It conducts public inquiries and research into a broad range of economic and social issues affecting the welfare of Australians. The Commission’s independence is underpinned by an Act of Parliament. Its processes and outputs are open to public scrutiny and are driven by concern for the wellbeing of the community as a whole. Information on the Productivity Commission, its publications and its current work program can be found on -

Proquest Dissertations

STAKEHOLDER PARTICIPATION AND COMMUNICATION IN THE PLACENTIA BAY/GRAND BANKS LARGE OCEAN MANAGEMENT AREA by ©Amy Tucker A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Geography Memorial University July 2011 St. John's Newfoundland and Labrador Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81837-4 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-81837-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Core 1..72 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA Débats de la Chambre des communes e e VOLUME 144 Ï NUMÉRO 037 Ï 2 SESSION Ï 40 LÉGISLATURE COMPTE RENDU OFFICIEL (HANSARD) Le mardi 31 mars 2009 (Partie A) Présidence de l'honorable Peter Milliken TABLE DES MATIÈRES (La table des matières quotidienne des délibérations se trouve à la fin du présent numéro.) Aussi disponible sur le site Web du Parlement du Canada à l’adresse suivante : http://www.parl.gc.ca 2177 CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES Le mardi 31 mars 2009 La séance est ouverte à 10 heures. l'Organisation pour la sécurité et la coopération en Europe (AP OSCE) sur la réunion du Bureau de l'Assemblée parlementaire de l'OSCE tenue à Madrid, en Espagne, du 28 au 30 novembre 2007. Prière *** [Français] AFFAIRES COURANTES LES COMITÉS DE LA CHAMBRE Ï (1000) [Français] INDUSTRIE, SCIENCES ET TECHNOLOGIE LA COMMISSION CANADIENNE DES DROITS DE LA L'hon. Michael Chong (Wellington—Halton Hills, PCC): PERSONNE Madame la Présidente, j'ai l'honneur de présenter, dans les deux Le Président: J'ai l'honneur de déposer sur le bureau le rapport langues officielles, le deuxième rapport du Comité permanent de annuel de 2008 de la Commission canadienne des droits de la l'industrie, des sciences et de la technologie intitulé « Étude de la personne. crise dans le secteur de l'automobile au Canada ». [Traduction] [Traduction] Conformément à l'alinéa 108(3)e) du Règlement, ce document est renvoyé d'office au Comité permanent de la justice et des droits de la Je présente ce rapport conformément à la motion adoptée par la personne. -

English Services

OFFICE OF THE OMBUDSMAN English Services ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 August 2012 Mr. Rémi Racine, Chair, Board of Directors, CBC/Radio-Canada Mr. Hubert T. Lacroix, President and CEO, CBC/Radio-Canada Members of the Board of Directors, CBC/Radio-Canada Dear Mr. Racine, Mr. Lacroix and Members of the Board of Directors: I am pleased to submit the annual report of the Office of the Ombudsman, English Services, for the period April 1, 2011, to March 31, 2012. Sincerely, Kirk LaPointe Ombudsman English Services Office of the Ombudsman, English Services | P.O. Box 500, Station A, Toronto, Ontario M5W 1E6 [email protected] | www.cbc.ca/ombudsman TABLE OF CONTENTS The Ombudsman’s Report 2 Le rapport de l’ombudsman des services anglais 7 (French translation of The Ombudsman’s Report) Complaints reviewed by the Ombudsman 13 APPENDICES I Chart: Number of communications received 74 II Map: Source of complaints 75 II Mandate of the Office of the Ombudsman 76 The report's cover is a Wordle of the Ombudsman's reviews, expressing in a "cloud" the prominence of each word in proportion to its frequency in the text of this year's reviews. THE OMBUDSMAN’S REPORT 2011-12 The Ombudsman is the public representative at CBC, so my annual report focuses on what I believe are the significant issues for the general public with CBC News, with its Journalistic Standards and Practices, and with the Office of the Ombudsman itself. There were a record 91 reviews of CBC news and information content by this Office in the 2011- 12 fiscal year.